Thu 9 Aug 2012

Reviewed by Marv Lachman: MARTIN H. GREENBERG & FRANCIS M. NEVINS, Jr., Editors – Mr. President, Private Eye.

Posted by Steve under Editors & Anthologies , ReviewsNo Comments

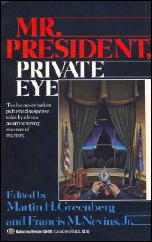

MARTIN H. GREENBERG & FRANCIS M. NEVINS, Jr., Editors – Mr. President, Private Eye. Ballantine, paperback original, December 1988. Ibooks, softcover, 2004.

I have long been fascinated by the “Presidential Connection,” the relationship between the mystery and the office of President of the United States. Following the triple traumas of Dallas, Vietnam, and Watergate, we had a publishing growth industry in which, literally, dozens of novels appeared featuring the President as either victim or villain.

Now the balance has shifted, and increasingly we find the man (so far) in the Oval Office appearing as detective. In recent years many of these stories have been about real Presidents. Three different authors have even written novels in which Theodore Roosevelt is featured, and he also solves a murder in Mr. President, Private Eye, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Francis M. Nevins, Jr.

The title is not exactly accurate, but you get the idea. Here are a dozen original stories, in each of which a real President gets to solve a crime. There is some evidence of hurried writing in this book, with anachronisms, always a danger in historical mysteries.

Also, in two of the weaker stories in the book, there is virtually no detection by Grant and Coolidge, respectively. However, there are also some stories which will give you a great deal of pleasure. Hoch has George Washington leave a dying message clue to a mystery which Abraham Lincoln solves half a century later.

Edward Wellen’s story about Millard Fillmore is surprisingly funny. Stuart M. Kaminsky’s mystery set in Missouri beautifully captures the simplicity and decisiveness of Harry Truman. Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Hoover detect at a Nevada silver mine in a story by Sharon McCrumb that I found to be the strongest in the book.

Finally, there is a clever K.T. Anders story about Gerald Ford which will make you clap your hand to your forehead and say, “Of course!”

Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.