Mon 8 Dec 2014

ADVENTURES OF THE FALCON – RADIO vs. TV, by MIchael Shonk.

Posted by Steve under Old Time Radio , TV mysteries[8] Comments

by Michael Shonk

Radio: 30 minutes. Blue Network: April 10 – December 29, 1943. Mutual Network: July 3, 1945 – April 30, 1950. NBC: May 7, 1950 – September 14, 1952. Mutual Network: January 5, 1953- November 27, 1954. Cast: Michael Waring was played by Barry Kroeger, James Meighan, Les Tremayne, Les Damon and George Petrie. (Source: On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio by John Dunning, Oxford University Press, 1998.)

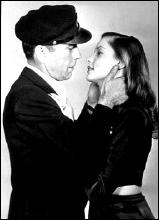

Television: 30 minutes. 1954, syndicated by NBC Films Division: A Bernard L. Schubert Production. Produced by Federal Telefilms Inc. Executive Producer: Buster Collier. Cast: Charles McGraw as Mike Waring.

I have been unable to find an episode of the series with Barry Kroeger or George Petrie as Michael Waring, The Falcon. I have found a site that offers free episodes from the series and at least one example of James Meighan, Les Tremayne and Les Damon. Click on this link to find the episodes I mention here and more.

“Murder Is a Family Affair.” November 27, 1945; Mutual Network. Cast: James Meighan as Mike Waring, The Falcon *** The format of the series will remain the same for most of the series, from the opening phone call from a woman about their date that night to the epilog at the end explaining loose ends.

The story has Mike and his girlfriend Nancy trying to protect the younger brother of a friend who had just been executed for murder.

This is the only sample of Meighan I can find, but it shows the film’s influences on the series. Mike is described as a freelance detective but his dialog and actions are not far from Tom Conway’s Falcon. The relationship between Mike and Nancy sounds more than something that lasts one episode and more like The Falcon and Helen Reed (Wendy Barrie) from the films.

“Murder Is a Bad Bluff.” November 1, 1948; Mutual Network. Cast: Les Tremayne as Mike Waring, The Falcon. Produced by Bernard L. Schubert. Written by Jerome Epstein. Directed by Richard Lewis *** A woman hires Mike to check out the man she hopes to marry.

As with most of the episodes, the mystery is weaken by a lack of suspects and logic. Nancy is gone and Waring is free to continue his alleged comedic womanizing ways, but now he is more likely than in the past to use his fists as well as his detective skills.

“The Case of Everybody’s Gun.” July 4, 1951; NBC. Cast: Les Damon as Mike Waring, The Falcon. Produced by Bernard L. Schubert. Written by Jerome Epstein. Directed by Richard Lewis. *** The Falcon is hired to check out a new charity. Shortly after Mike discovers it’s a con, his client is murdered.

Damon’s Falcon would never make one think of George Sanders’ version in the films. He played your typical smart-ass radio PI complete with unfunny banter between him and the cops. The mysteries have not gotten any better. Check out spot 11:47 for a good example of 50s radio and TV product placement. Listen to Waring and the cop for the episode verbally spar as both discuss with announcer Ed Herhily the joys of Miracle Whip.

The character’s continuity is a confused mess. The radio series credits Drexell Drake (Charles H, Huff) as the character’s creator. It also claims kinship to the films, the same films that give the character a different name (Gay Lawrence) and creator (Michael Arlen). Much has been written about this and I recommend you check out Kevin Burton Smith’s Thrilling Detective website for more.

The radio version of The Falcon under producer Bernard L. Schubert would make one more major change.

“The Case of the Vanishing Visa.” June 19, 1952; NBC. Cast: Les Damon as The Falcon *** Weary of the PI life, Mike Waring retires. Mike had been a top intelligence agent during WWII and the Army decides he is just the man they need, whether Mike wants to volunteer or not. He is sent to Vienna to smuggle out a woman who had been working for our side.

Becoming a spy didn’t mean there was not a crime or murder nearly every week for Mike to solve . The show, both on radio and TV, seemed determined to convince the audience there was little difference between the cases of a PI and an Army intelligence agent.

The radio series producer Bernard L. Schubert would continue with the series as it moved over to TV. Schubert would also produce such TV series as The Amazing Mr. Malone and Topper.

Broadcasting (June 15, 1953) reported Federal Telefilms Inc was finishing a TV pilot for The Falcon. It would be “presented by Bernard Schubert†and star Charles McGraw with script by Gene Wang and directed by George Waggner.

Obviously the pilot sold, as Broadcasting (April 19.1954) would report about the new series: “Federal Telefilms Inc, Hollywood, this week (April 12) goes before the cameras at Goldwyn Studios with Adventures of the Falcon, a Bernard L. Schubert Production, which NBC Film Division will distribute under a recently signed contract, reportedly in excess of a million dollars. Buster Collier is executive producer on the 39 half-hour films starring Charles McGraw in the title role. Ralph Murphy is signed to direct the first two films and Paul Landres, the second two.â€

According to a full-page ad in Broadcasting (May 10,1954), Harry Joe Brown was another producer involved in the TV series. Brown is best remembered for his partnership with Randolph Scott and director Budd Boetticher in the “Ranown Westerns†films.

The TV series continued The Falcon as an ex-PI turned Army intelligence agent. The casting of Charles McGraw turned Mike Waring into a more serious tough guy. As Army intelligence agent Mike took on cases all over the world from Western Europe to Macao to behind the Iron Curtain. One episode took place on the Atlantic Ocean. Mike would also take on cases all over the United States from Honolulu to New Jersey, from Chicago to New Orleans.

Currently there are over 25 episodes of the TV series available to watch on YouTube. Here are three examples.

“Double Identity.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzqJHAFcRto

Teleplay by William Leicester. Directed by Ralph Murphy. Guest Cast: Maralou Gray and Dan Seymour. *** Location: London. When the bad guys try to silence a freedom fighter by kidnapping his daughter, Mike poses as one of the bad guys in effort to rescue her.

Predictable, but can be forgiven since the episode was filmed sixty years ago. The episode is a good example of TV’s Falcon’s womanizing side.

“Rare Editions.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yp5nX6mKuiM

Teleplay by J. Benton Cheney. Directed by (name missing from video). Guest Cast: Nana Bryant, Charles Halton and Louis Jean Hexdt. *** Location: New York. A self-proclaimed helpless little old lady owns a bookstore that deals with rare books and illegal drugs.

Entertaining episode with a nice ending.

“A Drug on the Market.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cohk8gwm5lo

Teleplay by Gene Wang. Directed by Paul Landres. Guest Cast: Suzanne TaFel, Kurt Katch and Fred Essler. *** Location: Vienna. Due to several hijackings, the black market is the only source for a drug that could save a little boy’s life and many others. Mike’s job is to find the drug and break the black market ring.

Some unexpected twists highlight this episode.

NBC Films promotions for the series compared McGraw and The Falcon to Jack Webb’s Dragnet that NBC Films was syndicating as Badge 714. In Broadcasting (October 4, 1954) NBC Films announced Badge 714 had sold to 172 stations, Dangerous Assignment was sold to 174, and Adventures of the Falcon was sold to only 34 stations.