Sat 9 Jul 2016

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: ATTACK! (1956).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , War Films[2] Comments

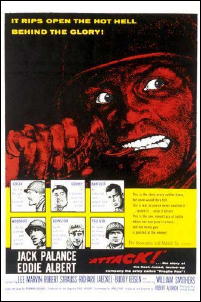

ATTACK! United Artists, 1956. Jack Palance, Eddie Albert, Lee Marvin, Robert Strauss, Richard Jaeckel, Buddy Ebsen. Director: Robert Aldrich.

Jack Palance, whose extensive movie career ranged from art house to grindhouse, starred in two World War II films directed by auteur Robert Aldrich; namely, Attack! (1956) and Ten Seconds to Hell (1959). I happened to watch the second of these two films about a year ago and went so far as to re-watch it about six months after that to get a better appreciation for Aldrich’s skillful – one might even say, singular – aesthetic.

As far as war films go, Ten Seconds to Hell is a fairly untraditional one, both in terms of subject matter and visual presentation. In that movie, Palance, along with Jeff Chandler, portray defeated German soldiers tasked with dismantling unexploded Allied ordinances left in the obliterated cities of the newly defeated Third Reich. Filmed in black and white, the movie presents the men in shades of grey, reflecting their morally compromised position as former German soldiers now nominally working for the Allies.

The film is not only bereft of active combat sequences, but it is also an exceedingly claustrophobic one, with scenes often filmed in confined, semi-interior settings in which the near possibility of death looms large over the proceedings. Death, such as it occurs, is the indirect, long-term result of prior human action rather than a fate delivered immediately at the hands of a gun or a tank turret.

The same cannot be said for Attack!, the first of the two Aldrich-Palance war film collaborations. In this earlier film, death is a cruel, personal fate that comes as the direct, immediate result of human action or, as in the case of the opening sequence of the film, human inaction. The movie opens fairly quickly into a gritty combat scene. In a battle set outside a Belgian city, Lt. Joe Costa (Palance) is hoping to get support for his men, but unfortunately for his men that doesn’t come to pass. The reason, as we soon learn is that the company’s CO, Captain Cooney (Eddie Albert in a stellar performance) is a drunken coward who never wanted to be in combat and just wants to make his father proud.

After the disaster on the battlefield, Costa, along with Lt. Harold Woodruff (William Smithers) are determined to let Lt. Col. Clyde Bartlett (Lee Marvin) know how little they think of Cooney. There’s a problem, however. Cooney hails from the same Southern town as Bartlett. Not only that, the two men have known each other since childhood and Bartlett once clerked for Cooney’s father, a local judge who we are to understand to be a big man in a small pond. Bartlett, who isn’t completely unaware as to what type of man Captain Cooney is, isn’t about to do anything to jeopardize his relationship with his friend’s politically influential father.

When Cooney orders Costa and his men into a yet another unnecessarily dangerous combat situation, Costa loses his cool. He threatens Cooney with death should the clearly incompetent captain falter again in his judgment. Not surprisingly, Costa and his men get pinned down in a farmhouse, only to be deprived of assistance from Cooney. It’s at that moment that we realize that Costa was deadly serious about returning back to base and murdering his increasingly erratic and inebriated captain.

This, of course, makes Attack! a particularly subversive combat film, one that the Defense Department officially refused to grant production assistance. The enemy as it is presented in Attack! is not so much the anonymous, nearly faceless German soldiers on the opposite side of the battlefield, but rather the company’s commanding officer.

Albert portrays the drunken, cowardly Cooney with nearly perfect combination of pathos and rage, making him an individual to be pitied as much as feared. Trust me when I say that the scene in which the mortally wounded Costa returns to confront the drunken, whimpering Cooney is wartime drama at its best.

Aldrich, far more than most directors, knew how to get the very best out of Palance, as his performance is simply breathtaking to behold in this gritty, morally complex war film. I wouldn’t go so far as to posit that Attack! is a particularly pleasant viewing experience, but it’s certainly a nearly unforgettable one.