August 2008

Monthly Archive

Sun 24 Aug 2008

M. K. LORENS – Ropedancer’s Fall. Bantam; paperback original; 1st printing, August 1990.

I’ll begin with a confession of sorts. Back when M. K. Lorens’ first book, Sweet Narcissus, came out, it looked particularly appetizing and I gave it a try, but I didn’t get very far.

Whether I wrote a review of the book, based on what I had managed to read, I have no idea. I suspect not, but I might have. Isn’t giving up on a book worth pointing out, as long as you say so very clearly and carefully?

And point out just why it was that you came to a dead end with it, without loudly and vociferously saying how greatly the author’s fault it was? (Even though in large part it may have been?)

In any case I haven’t come across it recently, “it” referring to the review which I may or may not have written, so the point is moot.

But the second book in the series recently surfaced, and remembering my earlier experience, I said to myself, here’s my opportunity to give the author another chance.

Lorens’ detective is the key attraction, a gent by the name of Winston Marlowe Sheridan who writes a “Gilded Age” series of mystery fiction himself, but under the well-disguised pseudonym of Henrietta Slocum. Slocum’s character in turn is named G. Winchester Hyde. How can one resist?

A portly fellow, Sheridan himself is a professor of literature at a New England college, and on occasion he finds himself involved in cases of murder, for which he places his sense of deduction on the line to solve.

In this case the dead man in Ropedancer’s Fall is John Falkner, whose one novel won a Pulitzer, but who was never able to write another one and who had been recently been reduced to being to PBS talk-show host, albeit a very good one. And as he was a long-time on-and-off friend of Sheridan’s, as well as a hopeless reclamation project, Sheridan takes his death very personally.

All well and good, but — and you knew this was coming, perhaps? — the telling is dense and nearly impenetrable — over 260 pages of small print — filled with Sheridan’s enormous entourage of friends and acquaintances, some closer than others, and their multitude of spouses and ex-spouses and intermingled offspring and foster children. And as the book goes on, the list of the above gets longer and longer — a snowballing effect figuratively if not literally.

But given some time to get to know them, the list of characters does becomes manageable, and the writing, while dense, is also delightfully incisive and witty. Eventually, though, it begins to dawn on the reader (or at least this one) that the investigation is going absolutely nowhere. Wheels within wheels, but all of them are spinning and spinning, and spurting up little but slush.

Skipping to the end, after about 160 pages, and sure enough, nothing happened in Chapter Twenty that couldn’t have been predicted after reading Chapter Two.

Recommended if you’re a fan of clever, witty repartee between clever, witty people. (Do NOT read any sense of sarcasm into this statement.) Not recommended if you like a hands-on mystery to solve in your detective fiction.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA. [Expanded from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

LORENS, M(ARGARET) K(EILSTRUP). 1945- . Pseudonym: Margaret Lawrence. Series Character: Winston Marlowe Sherman, in all. [The distinctive artwork for the covers you see is by Merritt Dekle.]

Sweet Narcissus. Bantam, pbo, August 1989. [corrected year !]

Ropedancer’s Fall. Bantam, pbo, August 1990.

Deception Island. Bantam, pbo, November 1990.

Dreamland. Doubleday, hardcover, April 1992; Bantam, pb, March 1993.

Sorrowheart. Doubleday, hc, April 1993; Bantam, pb, April 1994.

LAWRENCE, MARGARET. Pseudonym of Margaret Keilstrup Lorens. SC: Midwife Hannah Trevor, in the first three; her daughter Jennet, who is deaf, appears in the fourth. Setting: Maine, 1780s.

Hearts and Bones, Avon, pbo, October 1997. [Nominated for Edgar, Agatha, and Anthony awards]

Blood Red Roses, Avon, pbo, October 1998.

The Burning Bride, Avon, pbo, September 1999.

The Iceweaver, Morrow, hc, July 2000. Trade paperback: Harper, July 2001.

Sat 23 Aug 2008

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

P. C. DOHERTY – The Assassins of Isis. St. Martin’s, hardcover, November 2006. Originally published in the UK by Headline: hardcover, August 2004; trade paperback, August 2005.

In this fifth novel in the Egyptian series featuring Lord Amerotke, Chief Judge of Pharaoh Queen Hatusu, tombs of the Pharaohs are being looted in the Valley of the Kings, a retired military hero, General Suten, is improbably murdered by a horde of vipers that attack him on his rooftop sanctuary, and four virgin handmaids have disappeared from the Temple of Isis.

Not improbably, Amerotke finds that the events are linked and that they pose a threat to the Pharaoh herself.

I read this at a single sitting, propelled through it by the dazzling pyrotechnics of Doherty’s intricate plotting, and by the richly embroidered splendor of the court setting in which much of the novel is set.

JANE JAKEMAN – In the City of Dark Waters. Berkley Prime Crime, hardcover, May 2006.

In this sequel to In the Kingdom of Mists, French Impressionist artist Claude Monet’s role is considerably reduced although there are a few passages describing him at his easel in Venice that have some of the magic of the earlier novel.

There’s a new protagonist, British lawyer Revel Callendar, who’s doing a reduced version of the once obligatory European Tour in Venice when he’s drafted by the British consul to do some paperwork for the once powerful Casimiri family after the death of the principessa, a British citizen by birth and a Casimiri by marriage.

The relationships in the crumbling, gloomy Casimiri palazio are as murky as the Venetian canals, and even more dangerous to outsiders. As if that situation weren’t enough to occupy him, Callendar, who’s introduced to Monet by the consul, accepts a commission from Monet to go to Paris to look in on the situation in the family of Monet’s wife, Alice, whose first husband has been murdered.

There’s some similarity between the murders in the two families, but Jakeman’s handling of the interlocking story lines doesn’t quite come together, and the introduction of Monet and the Parisian episode, while interesting (and based on an actual event), seems too calculated to be entirely convincing. All in all, something of a disappointment.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA:

The Lord Amerotke Novels by P. C. Doherty. [Dates are those for the UK editions, all published by Headline.]

The Mask of Ra, 1998.

The Horus Killings, 1999.

The Anubis Slayings, 2000.

The Slayers of Seth, 2001.

The Assassins of Isis, 2004.

The Poisoner of Ptah, 2007.

The Claude Monet novels by Jane Jakeman.

In the Kingdom of the Mists, 2004.

In the City of Dark Waters, 2006.

Fri 22 Aug 2008

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

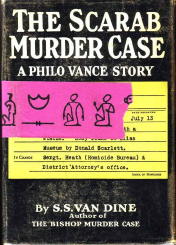

S. S. VAN DINE – The Scarab Murder Case.

Charles Scribner’s Sons, hardcover, 1930. Cassell, UK, hardcover, 1930. Paperback reprints include: Bantam #96, 1947; Graphic #89, 1954, abridged; Scribner’s, 1984. British film: 1936, with Wilfrid Hyde-White as Vance, Graham Cheswright as Markham, and Henri De Vries as Dr Bliss. (No prints are known to exist.)

Philanthropist Benjamin H. Kyle is found murdered in a private museum run by Egyptologist Dr Mindrum Bliss. Philo Vance becomes involved when Donald Scarlett, a British college friend now working for Dr Bliss, arrives in a terrible haste. Scarlett had gone to the museum, discovered Kyle’s body, and then left rapidly because he did not want to get involved. He has come to Vance for help.

DA John Markham and his police department cohorts are soon on the job, assisted by Vance. It transpires Kyle was funding Bliss’s Egyptian expeditions and when found is clutching a financial document drawn up by Bliss, whose scarab cravat pin is on the floor nearby.

It looks bad, especially given the only fingerprints on the statuette that crushed Kyle’s head belong to Bliss, and so does a shoe with a bloody sole. Is it an all too obvious attempt to pin the murder on him? If so, why?

Suspects include half-Egyptian Mrs Meryt-Amen Bliss, who is a lot younger than her husband, and her Egyptian servant Anupu Hani, who insists Dr Bliss’s excavations are sacrilegious tomb plunderings.

Assistant curator Robert Salveter, Kyle’s nephew, not only seems overly interested in Mrs Bliss but will receive a large inheritance under Kyle’s will. The servants seem a shifty pair as well — Dingle, the cook, who hints she may know more than she lets on, and butler Brush, who goes about looking terrified.

My verdict: The Scarab Murder Case is a book or two into the Vance series and his verbal embroidery has toned down considerably although still retaining his distinctive “voice”, while the narrator’s footnotes proliferate as usual.

Markham is now a personal friend of Vance’s, remaining rather a Doubting Thomas when it comes to the psychology of criminals, Vance’s preferred method of solving crimes.

Fortunately Vance is extremely knowledgeable in matters ancient Egyptian, which also comes in very handy in this instance. Those keen on Egyptology will enjoy certain nuggets of interest strewn here and there, although overall the pace of the novel is slow.

I guessed the identity of the culprit and suspect many readers will too, but as for proving it, ah, that is a task only Philo Vance could accomplish, and accomplish it he does despite the clouds of ever-present cigarette smoke and various devilish machinations.

E-text: http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200361.txt

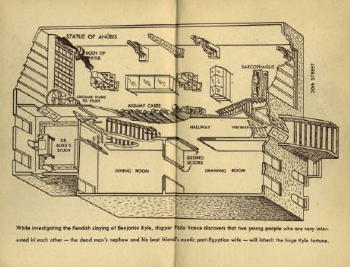

[BONUS.] For those of you who love maps in their mystery reading material, this is for you. From inside the front cover of the Bantam edition comes this two-page layout of the murder scene, thanks to Bruce Black and the bookscans website:

Thu 21 Aug 2008

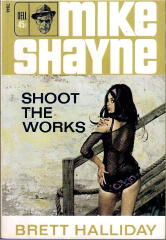

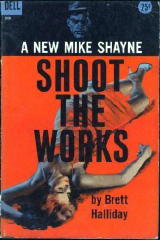

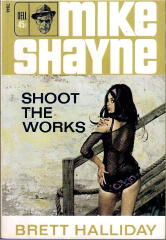

BRETT HALLIDAY – Shoot the Works.

Dell 7844; paperback reprint, December 1965; cover: Robert McGinnis. Earlier paperback edition: Dell 988, September 1958; cover: Robert Stanley. Hardcover edition: Torquil / Dodd Mead, 1957.

According to the blurb on the hardcover edition, this was the 30th Mike Shayne novel that Brett Halliday wrote, which is to say Davis Dresser, who was still actively writing them in 1957. It takes place in Miami, with all of the usual players in place: Lucy Hamilton, Shayne’s secretary and close lady friend; Chief Will Gentry, of Homicide; and Timothy Rourke, ace reporter of the Daily News.

I may be wrong, but while I can’t tell you in which book the four of them all appeared in together for the first time, I think they were in all of them from at least this point on – the point of time being this book, Shoot the Works, of course.

It’s Lucy who gets Mike involved in this one. The mother of one of her closest friends comes home early from a trip to New York City only to find her husband shot to death in their apartment. Worse, he has a bag packed on the bed – and two airplane tickets to South America in his pocket.

Against his better judgment, at the urging of the dead man’s wife, who wishes to avoid a scandal and the notoriety that might end her daughter’s precarious pregnancy, Mike takes the tickets and withholds the evidence from Gentry.

This has two serious repercussions. Gentry knows Shayne is holding something back, but he doesn’t know what; and secondly, Shayne finds himself in a serious bind: when his client is suspected, there’s no way he can get on Gentry’s good side, as the tickets will make the case against her even stronger.

This is a murder case (and investigation) from beginning to end, with very little room left for anything that passes for more than surface characterizations. Shayne seriously flirts with a couple of ladies who seem completely willing to let him have their way with them – his relationship with Lucy seems to allow him the possibility, as far as he’s concerned, that is.

There are a couple of finely devised twists and turns of the plot, mostly based on statements and actions misinterpreted and misunderstood – nicely done – and one piece of evidence that Shayne obtains under unusual conditions, and I caught the significance of that, even though it isn’t brought up again until much later.

The only drawback to this detective puzzle of a novel – other than the incessant smoking and sipping down cognacs – if that’s a drawback, that is – is the paucity of murder suspects involved. One might simply guess at the killer’s identity, and by the laws of probability one might actually be right.

Without the pleasure of putting the facts together as they should be put. Otherwise where’s the satisfaction?

Wed 20 Aug 2008

MARY FITT – Mizmaze.

Penguin, UK, reprint paperback: 1961. Hardcover editions: Michael Joseph, UK, 1959; British Book Centre, US, 1959.

Perhaps it’s wrong-end-to in doing so, but I think I’ll begin this time by listing all of mysteries that Mary Fitt wrote, either under that name or her own, plus one other pen name. (I think you may be as surprised as I was at how long a list it turns out to be.)

Courtesy, then, of Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

FITT, MARY. Pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman, 1897-1959; other pseudonym: Stuart Mary Wick.

Murder Mars the Tour (n.) Nicholson 1936 [Austria]

Three Sisters Flew Home (n.) Nicholson 1936 [England]

Bulls Like Death (n.) Nicholson 1937 [Berlin]

The Three Hunting Horns (n.) Nicholson 1937 [France]

Expected Death (n.) Nicholson 1938 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Sky-Rocket (n.) Nicholson 1938 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Death at Dancing Stones (n.) Nicholson 1939 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Murder of a Mouse (n.) Nicholson 1939 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Death Starts a Rumor (n.) Nicholson 1940 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Death and Mary Dazill (n.) Joseph 1941 [Supt. Mallett; England] US title: Aftermath of Murder.

Death on Herons’ Mere (n.) Joseph 1941 [Supt. Mallett; England] US title: Death Finds a Target.

Requiem for Robert (n.) Joseph 1942 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Clues to Christabel (n.) Joseph 1944 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Death and the Pleasant Voices (n.) Joseph 1946 [Supt. Mallett; England]

A Fine and Private Place (n.) Macdonald 1947 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Death and the Bright Day (n.) Macdonald 1948 [Supt. Mallett; England]

The Banquet Ceases (n.) Macdonald 1949 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Pity for Pamela (n.) Macdonald 1950 [England]

An Ill Wind (n.) Macdonald 1951 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Death and the Shortest Day (n.) Macdonald 1952 [Supt. Mallett; England]

The Night-Watchman’s Friend (n.) Macdonald 1953 [England]

Love from Elizabeth (n.) Macdonald 1954 [Supt. Mallett; England]

The Man Who Shot Birds and other tales of mystery and detection (co) Macdonald 1954 [Supt. Mallett; England]

Sweet Poison (n.) Macdonald 1956 [Supt. Mallett; England]

The Late Uncle Max (n.) Macdonald 1957 [Mediterranean Island]

Case for the Defence (n.) Macdonald 1958 [England]

Mizmaze (n.) Joseph 1959 [Supt. Mallett; England]

There Are More Ways of Killing… (n.) Joseph 1960 [England]

FREEMAN, KATHLEEN. 1897-1959. Pseudonyms: Mary Fitt & Stuart Mary Wick.

The Intruder, and other stories (co) Cape 1926

Gown and Shroud (n.) Macdonald 1947 [Academia; England]

WICK, STUART MARY. Pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman, 1897-1959; other pseudonym: Mary Fitt.

And Where’s Mr. Bellamy? (n.) Hutchinson 1948

-The Statue and the Lady (n.) Hodder 1950

Kathleen Freeman herself was a British classical scholar who attended the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire in Cardiff, where she was appointed Lecturer in Greek in 1919, but resigning from the University in 1946.

As a writer of detective fiction, the author’s primary series character, Supt. Mallett, began his career in 1938, when the Golden Age of Detection was in full sway, and did not end until this book, Mizmaze, in 1959. Quite a career, 18 books in all, for a fictional character whom I’m sure none but the most devout aficionados remember. (The latter is a category which I unhappily confess does not include me, as this is the first book by Mary Fitt that I’ve ever read.)

And in spite of some serious problems I found with the book, it will not be my last. Some of her mysteries were published in the US by Doubleday’s Crime Club imprint, for example, and while I have not read them, I do have them.

But get to the book itself, shall I? It’s one of those old-fashioned detective stories in which the murder takes pace (or already has taken place) in Chapter One, and there’s nothing else in the book but the solving of the crime.

Well, that and sorting through all of the relationships between the characters, some of which is relevant to the case and some of it not, but it’s all part and parcel of solving the crime, is it not?

Dead is the patriarch of the Hatley family, found with fatal head injury in the center of the maze at his home, both called Mizmaze. The murder weapon: a croquet mallet. Surviving family: two daughters, one Alethea (Lethy), who never can be relied on to tell the truth, her father’s pride and joy, the other Angela, a devilish girl who her father seems to have intensely disliked. A dysfunctional family: yes, no doubts about it.

Alethea’s former husband is also visiting upon the fatal weekend, along with his new wife, a former actress more than 30 years older than he. (The victim had much to do with the breakup of his daughter’s marriage.) Two others are possible suspects: a 6 foot 8 giant with pituitary problems, in love with Althea but Angela in love with him, plus his mother.

More than you wanted to know, I suppose. Solving the case are Superintendent Mallet and his close friend, Dr. Fitzbrown, but truth be told, it is the latter who does the bulk of the questioning of the suspects.

From the summary so far, I imagine that you already have a good grasp of the story line (and more importantly, whether or not this is a book for you.) And by the way, that the deadly blunt instrument was a mallet did not escape Fitzbrown’s attention, either. He comments on it immediately.

Problems, as previously alluded to: lapses in continuity in the telling. On page 23, Fitzbrown says that Hatley was followed by the killer into the maze. On page 24, he clearly states that someone with deadly intent was waiting for Hartley at or near the center of the maze.

More. On page 132 Horick (the giant) comes downstairs from his sickbed to confront the rest of the entourage. On page 143 he comes down again as if for the first time, surprised to see them all there.

There is also a previously never-mentioned spouse of one of the participants who shows up without notice at nearly the last moment, and a killer who suddenly turns into a madman (or woman) at the end, claiming responsibility and threatening to kill all of the others, the pair of sleuths included, only to fall victim himself (or herself) to a deus ex machina which is as amusing as it is fortuitous.

And there’s the key right there, only I didn’t realize it until I was done, and indeed I did finish it, flaws and all, staying up 30 minutes past my planned bedtime to do so. I’m sure it wasn’t meant to be so, but if I were to be asked about an unintentional spoof of Golden Age detective stories, right now Mizmaze would be an example that I’d point to first.

I suppose that may sound unkind. I don’t mean it to be, and so far I can’t explain my attraction to this book any better than I am. The characters are more than eccentric — you might even call them just plain looney — but they’re nonetheless real enough: devious, worried, clever, burdened down by life and love — or entirely human, in other words.

Even Dr. Fitzbrown finds one of the women attractive enough to spend a short minute with her in a kiss, even though she’s still very much a suspect — and I wonder how that turns out. The book ends abruptly with the killer’s downfall, and this is the last appearance in print of either sleuth.

[COMMENT] 08-21-08. I have discovered that I am not the only mystery fan who has struggled with Mary Fitt and her detective fiction. On the John Dickson Carr forum, I have found a long post by Xavier Lechard in which he tries to come to grips with her books. The following except should demonstrate, and still be within the bounds of fair usage:

“But did Fitt write Golden Age mysteries? As far as chronology is concerned, there isn’t a doubt about it. Stylistically, however, the matter is much more debatable. If we admit that Golden Age mysteries are about a crime and its resolution through logical reasoning by an amateur or professional detective, then we have a problem with Death and Mary Dazill which is almost devoid of any detection, as well as with Clues to Christabel which has no detective in the proper sense….”

And may I recommend Xavier’s own blog to you? Entitled At the Villa Rose, it’s jam-packed full of serious commentary and replies on the state, status and structure of the Golden Age detective story.

Tue 19 Aug 2008

M. C. BEATON – The Skeleton in the Closet.

St. Martin’s; 1st paperback edition, March 2002. Hardcover edition: St. Martin’s, March 2001.

Have you ever picked up a book just as you’re climbing into bed, intending to give it a good five minutes before turning out the light, going perhaps a chapter or two, just to see how interesting it is? And then, forty or fifty pages later, discovering that thirty minutes have gone by, and you haven’t even noticed?

I have, and I just did. This is not one of Beaton’s series novels — she actually has two going, as I suppose everybody knows: the Agatha Raisin mysteries, and separately, the cases of Scottish constable Hamish Macbeth. This one’s a stand-alone, a cozy little tale of murder and amateur detection, English village style.

And the very first line is a keeper: “In the way that illiterate people become very cunning at covering up their disability, Mr. Fellworth Dolphin, known as Fell, approaching forty, was still a virgin and kept it a dark secret.”

Living with his mother, working as a hotel waiter, and at his age still under her thumb, Fell is one of those people that life seems to have passed by. Until, that is, his mother, unloved, dies, and he discovers that he is the heir to a small fortune. “But that’s impossible!” Fell exclaims to the lawyer. “We never even had a television set.”

In his deceased father’s old desk he also discovers a hidden metal box containing 50,000 pounds in currency, stacked in neat bundles. Caught by surprise by an aunt who offers to move in with him, Fell invents a fiancee, Maggie Partlett, a waitress at the same hotel. Maggie is agreeable, moves in (platonically) and — no gold-digger she, don’t get the wrong idea — together they become pair of reluctant sleuths, digging deeply into Fell’s past. (Where did the money come from?)

While the first forty or fifty pages are the best, there are many more twists and turns in the plot to come — I haven’t given it all away, by any means. Fell and Maggie are hardly professionals at work, mind you, and eventually there’s a huge coincidence that’s a bit of a problem, one so large that even the author (through Maggie) is forced to comment on it — “Do you believe in God, Fell?”

But other than that, unless you’re such a devout fan of hard-boiled mysteries that you never read anything else, this neat little mystery will go down awfully smooth.

— March 2002

[UPDATE] 08-19-008. According to Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, M. C. Beaton is the primary mystery-writing pen name of Marion C. Gibbons, 1936- . (Gibbons is her married name, with the “C.” likely to be Chesney, her maiden name.)

Before turning to mystery fiction, and writing as Marion Chesney, she was well-known and very popular as an author of regency romances. She’s also written books as by Sarah Chester (one romantic suspense novel in CFIV) and Jennie Tremaine (one additional romantic suspense novel).

Other books under these last two names, or those she’s written as Helen Crampton, Ann Fairfax and Charlotte Ward, are likely to be pure romances, and almost always historical fiction.

Written as by Marion Chesney, but published too late to appear in CFIV, is a new series of Edwardian mysteries featuring Lady Rose Summer, the daughter of the Earl of Hadshire, and her companion in solving crimes, Captain Harry Cathcart, the son of a baron and an invalid from the Boer War who’s set up a private detective agency for the well-to-do:

Snobbery with Violence (2003)

Hasty Death (2004)

Sick of Shadows (2005)

Our Lady of Pain (2006)

Sun 17 Aug 2008

A short while ago this evening I uploaded Part 29 of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

The data, as usual, consists largely of miscellaneous material, ranging in terms of authors from Arthur A’Beckett (new biographical facts) to Mabel E. Wotton (full name, along with both birth and death dates).

Some of the longer entries are ones for comic book writers Brian Azzarello, Will Eisner and Frank Miller, whose detective and crime fiction in graphic novel form have now been added.

Eisner, for example, was the creator of The Spirit, whose exploits will be coming soon to a movie theater complex somewhere near you.

Others with long entries include Bernard Capes, whose crime fiction appeared between 1898 and 1919; R. Chetwynd-Hayes, whose collections of ghost stories are given in detail, including the adventures of psychic investigators Frederica Masters & Francis St. Clare; David Hume, some of whose books have recently been published in the US for the first time by Ramble House; and Eric Leyland, all of whose novels about adventurer David Flame are now included, although designed primarily for younger readers. (The cover of one of these books is shown to the left.)

Three additional film adaptations of books by Ed McBain are included, along with some first US editions of Gladys Mitchell‘s detective fiction, published recently by Rue Morgue Press.

Deaths occurring in 2008 are reported for Eliot Asinof, Robert Asprin, Nicholas Bartlett, William Buchan, Algis Budrys, Glenn Canary, Thomas Disch, George Furth, George Garrett, Simon Gray, Robert Harling, Jack Lynch, Maureen Peters, Malvin Wald, and Donald James Wheal.

I regret no longer having the time to post death notices and obituaries for authors such as these on the blog. Some are more important to the field of crime fiction than others, of course, but they all deserve a mention.

I’m also way behind in adding my annotations to the Addenda. One of my more immediate goals is to improve my performance in that regard. In fact, I am still trying to catch up on emails that arrived while I was away at the beginning of the month and soon thereafter. If you’ve sent me something I haven’t replied to recently, I hope you’ll be patient a while longer.

Or nudge me. With a pointed stick, if need be!

Sat 16 Aug 2008

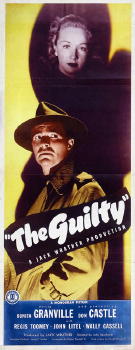

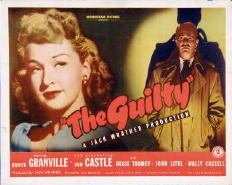

THE GUILTY. Monogram, 1947. Bonita Granville, Don Castle, Wally Cassell, Regis Toomey, John Litel. Screenplay: Robert Presnell Sr., based on a story by Cornell Woolrich. Producer: Jack Wrather. Director: John Reinhardt.

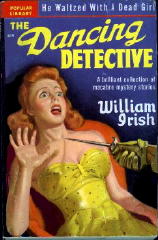

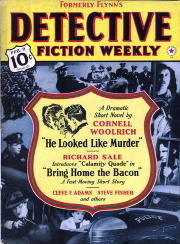

[WILLIAM IRISH – “Two Fellows in a Furnished Room.” Long novelette included in The Dancing Detective, Lippincott, hardcover, 1946; Popular Library 309, ppbk, January 1951. Originally published as “He Looked Like Murder,” as by Cornell Woolrich, Detective Fiction Weekly, 8 February 1941.]

Some of the books on noir films like this movie quite a bit, but if I were writing one, the one I’d write wouldn’t be one of them. It’s a noir film all right – how could it not be, based as it is one of the originators of noir fiction, Cornell Woolrich?

Poor production values, for one possibility, is the answer, and even more poorly conceived changes and/or additions to the story, both of which, in my opinion, occurred in the making of The Guilty.

Woolrich’s story is long but compact, complete in itself, and full of his usual “things gone wrong in an everyday world” motif. One fellow of two sharing a room together asks the other to stay away for a couple of hours while his girl friend comes over. After Stewart Carr, the one who was asked to leave, returns – he’s also the one telling the story – the girl’s mother calls, asking where her daughter is.

She’s disappeared, and when Carr’s roommate John Dixon begins to act more and more suspiciously, Carr tries to stay on his side, but he begins to find it more and more difficult to do so. This is the kind of mess you get into, suggests Woolrich in his role of author, when you start to hide things you needn’t, you panic, and all you end up doing is making the mess even worse.

Fate, at nearly the last minute, steps in, however, before Dixon is picked up by the police and (more than likely) railroaded off to the death house. The friendship is over, of course, even though things worked out OK in the end.

Woolrich’s stories are almost always a little over the top, some more than others, and this is one of them. It’s a little too short for a movie, even one only 71 minutes long, so of course some additional material has to be added.

Some of what was done is understandable, or at least you can figure out why. I mentioned in the opening credits that Jack Wrather was the producer. In 1947, the same year that The Guilty was made, he and Bonita Granville, the star of the film, were married. And any story in which the only major female role is someone who dies in the first chapter is hardly a part for any leading lady to consider, married to the producer or not.

Solution? Double the part by giving the girl who dies (Linda) a twin sister (Estelle) who’s as manipulative-of-men bad as the dead girl was good. More, to complicate matters – none of which appeared in the original story, of course – make Carr fall for the bad girl after she was dumped by the roommate for the good girl, who’s the one who died, with (as in the story) the roommate strongly suspected of doing the killing.

I don’t recall ever seeing it, but in 1946, the year before The Guilty was made, Olivia De Havilland played a similar pair of good and bad twins in The Dark Mirror. Apparently one takes ideas wherever one can get them. Similar story lines probably occurred even before that, and probably several times over.

In any case, it takes a while to sort things out – luckily the girls meet on the screen together only once, and after all, Linda leaves the film soon after anyway. What seemed awkward to me at the beginning, though, was the framing device of Carr coming to the bar around the corner from the room where all this happened, some six months later, waiting for a girl to show up – we don’t know who, of course, at the beginning.

The purpose? To help extend the ending of the novelette to include a newly devised one. A twist, in other words, as to who the real killer was.

And here’s where everything really does goes wrong. Retrofitting a new ending to a detective story – and that is exactly what this is – one in which the clues are already pointing to one person – simply can’t be done without a complete rewrite, in which case you may as well write a brand new screenplay and leave Woolrich’s tale out of it altogether. What’s done is done, but even so, Pfui is what I say to the new ending.

One other thing. Jack Wrather is described as an oil millionaire, but he certainly didn’t sink any money into this movie. (In 1954 he bought the rights to The Lone Ranger, and later on Sergeant Preston and Lassie, eventually producing all three as television series.)

But in 1947 the sets in The Guilty are bare bones to the max. Some observers suggest that this only heightens the noir mood of the film, emphasizing the bleakness of the characters’ fates.

To some extent I can see what they’re saying, but when all you can see in the film are little more than solid but completely stagey sets, all I can say is another Pfui. (Regretfully. I do want to make that clear.)

I guess I was wrong; there were two other things I meant to add a moment ago, not just one. Bonita Granville was only 24 when she made this movie, but she’d already had a long career behind her in making films. She was, of course, most well known for the four movies she made in her teens as Nancy Drew, girl detective.

Girlishly buoyant and full of enthusiasm in the role, one she may have been perfect for, if she had not married Wrather, she may have had a even longer career playing “bad” girls in noir films such as The Guilty. I don’t believe this photo I found of her is necessarily related to her role in that movie, but if not, it’s close enough, and I think it will show you more what I mean than I can say in words.

Unless one of the words is Huzzah!

Fri 15 Aug 2008

L. A. TAYLOR – Only Half a Hoax.

Walker; paperback reprint, 1986; hardcover edition, 1983.

First of all, let me say it is about time [1987] Walker started reprinting some of their American detective fiction in paperback. In the past four or five years Walker seems to have come from nowhere to become of one of the leading publishers of hardcover mysteries, most of which seems to have been ignored by other paperback companies.

(They have been reprinting their British mystery fiction in paper for several years now, but for the most part, I find myself too easily bored with the general run of “thriller” this entails.)

I also have to say that I’m glad they chose to include the Taylor books in their first batch of releases. (His/her second book, Deadly Objectives, is also now out.) I have to confess that I had the chance to pick this one earlier in hardcover, and I turned up my nose at the chance. I mean, after all, a detective whose hobby is chasing down reports of UFO’s in the Minneapolis area?

No offense intended to Minneapolitans. I’m sure it must be a terrific place to live, in spite of the comments of J. J. Jamison (the aforementioned detective) sometimes to the contrary. But flying saucers and detective fiction seems such an incongruous combination, I couldn’t imagine myself reading such balderdash, much less enjoying it.

But enjoy this book, I did. Even though J. J. (his full-time job a computer engineer) is pretty much a naive sort of neophyte at the detective business, the case he enters into is breezily told, and is easily recognized as a throwback to the wacky cases of homicide that were exceedingly popular back in the 1940s.

And reflecting back on it now, the plot doesn’t really make a lot of sense. If you’re planning a murder, why should your first impulse be to set up an elaborate fake UFO in order to draw attention away from the act you’re about to do?

When J. J. investigates and finds the body, he’s first suspected of complicity, then becomes the killer’s target. Chronologically: (1) his brakes are tampered with, (2) he is nearly run down while bike riding, (3) his house is set on fire, and (4) he is dumped in the tiger cage of the Minnesota Zoo. Maybe I missed one.

The point of all this is to keep the reader’s mind off the fact that there really are very few suspects, and the clues are a little too obvious to withstand direct attention. It takes the last ten pages to wrap everything up is well, which is far too long for a mystery properly told. Even in the 40s, though it took time to make the illogical satisfactorily plausible.

In spite of my earlier comments, Taylor does well at this sort of thing, and throws in a little bit of surprise to boot.

— From Mystery.File 1, January 1987 (slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 08-15-08. Several things are clear from this review, reading through it this evening for the first time myself in over eleven years. First of all, and most importantly, it is clear that I did not know whether or not L. A. Taylor was male or female. It is much easier to answer questions like this now, what with the Internet, and the handy assist of Al Hubin’s Revised Crime Fiction IV:

TAYLOR, L. A. [Laurie Aylama Taylor Sparer]. 1939-1996. Series character: JJ = J. J. Jamison

Footnote to Murder. Walker 1983. JJ

Only Half a Hoax. Walker 1983. JJ

Deadly Objectives. Walker 1984. JJ

Shed Light on Death. Walker 1985. JJ

Love of Money. Walker. 1986

Poetic Justice. Walker. 1988

A Murder Waiting to Happen. Walker 1989. JJ [set at a Minnesota SF convention]

Besides the mysteries listed above, she also wrote Blossom of Erda, a science fiction novel; Cat’s Paw, a fantasy; and (possibly) Women’s Work a collection of both SF and fantasy. (I’ve not yet found confirmation that the latter was ever published.)

It therefore now comes as no great surprise to find the SFnal elements that are so obviously present in Only Half a Hoax. As you’ve read, I found them semi- objectionable in 1986. I’d like to think I’d find them less so now.

After her death Ms. Taylor’s husband had her final novel published: The Fathergod Experiment, described online as “a quirky, complex, interesting tale that combines court intrigue with mysteries both scientific and criminal, and a thoroughly satisfying story of an orphan rising from obscurity and oppression.”

I’ve forwarded a more complete description to Al. It appears that the books ought to be included in CFIV, at least marginally. (Added later: He agrees. The book will appear in Part 29 of the online Addenda.)

Also of note in the review, at least to me, was my mammoth snobbish putdown of British thriller fiction. You can blame my younger self for that, but not this present fellow who I am now.

Thu 14 Aug 2008

THE DEVIL-SHIP PIRATES. Hammer Films/Columbia, 1964. Christopher Lee, Barry Warren, John Cairney, Suzan Farmer, Michael Ripper, Duncan Lamont, Andrew Keir, Natasha Pyne. Screenwriter: Jimmy Sangster. Director: Don Sharp.

This is the movie that’s paired with The Pirates of Blood River (1960) in a recently released boxed set of Hammer films entitled “Icons of Adventure.” (You can go back and read my review of the latter here.) Both star Christopher Lee as the head of their respective ragtail crew of pirates, both were written by Jimmy Sangster, and that’s not all.

They both have the same basic story line. In the commentary track for this film, Jimmy Sangster even admits it, calling it your basic “Humphrey Bogart in The Desperate Hours” plot, in which a gang of escaped killers take over a suburban household (or a gang of pirates take over an isolated village) only to find their captives not quite to be the pushovers they expected.

In The Devil-Ship Pirates, the pirates have been aligned with Spain at the time of the defeat of the Armada, and as one of the ships that survived but unable to return to Spain — and having no real allegiance to that country — land near an isolated village which they then take over, on the ruse that the Spanish won. The local mayor is all too willing to kowtow to the town’s new masters, but not all of the townsfolk are so readily inclined.

Comparing the reviews of both movies which I’ve discovered online, results as to which movie was favored over the other are mixed, but mostly it boils down to which of the pair you happen to watch first.

Myself, I think that the basic idea was fresher in Blood River, and the actors were better (Oliver Reed was in the first one, for example, and not the second) and unless my biases are showing, and I’m sure they are, even the actresses were comelier in the first. (But do take note of the lady above, the daughter of the local mayor and the rebel hero’s girl friend.)

Granted, what the first movie lacked were any scenes with a real boat in it. This one does, although I suspect that the ships shown firing cannons at each other in the opening scenes came from storeroom footage. But the ship that lands on the English shoreline, right up to the water’s edge, was carefully constructed and used as one of several primary filming areas.

The money that was spent on it was put to good use, but as the commentary reveals, the ship suffered a serious accident during the course of the movie, and it goes up in flames at the end – gloriously done, but perhaps as a direct consequence, The Devil-Ship Pirates was the last pirate film that Hammer Films ever did.

Overall, in spite of the second-hand story line, there is much to find in this movie to be entertained by. The English village was painstakingly re-created (and almost surely was used again, both before and after), and the colors throughout the film are gloriously vivid. Spectacular, as a matter of fact, as I hope these photos will attest to.

« Previous Page — Next Page »