September 2008

Monthly Archive

Sat 6 Sep 2008

LEWIS B. PATTEN – Prodigal Gunfighter.

Berkley F1241; paperback original, 1966. Signet, 1976; Signet Double, 1979; Leisure Double, 1994.

Lewis B. Patten’s first book, Massacre at White River, came out from Ace in 1952, and his writing career continued right up until he died in 1981, when Track of the Hunter came out, also as a paperback original, this time from Signet.

He was incredibly prolific. In a thirty-year span he produced something like 90 novels, including books as by Lewis Ford, Len Leighton (with Wayne D. Overholser) and Joseph Wayne (also in collaboration with Overholser).

As one of the next generation of western writers, Patten’s all of novels came out very much in the post-pulp era but (as far as I know) also still all very much in the “code of the west” tradition. It’s certainly difficult to generalize on the basis of one book, and Prodigal Gunfighter is the only book of his that I’ve read in several years, and probably more than that.

Not that Patten didn’t write for the pulps. Starting in 1950 he had a score or more shorter works that appeared in magazines like Mammoth Western, Thrilling Western, Frontier Stories and so on. His name is certainly more identified with novels, however, and in his heyday, he was cranking them out like almost nobody else.

And he was published in hardcover as well. He may have begun in softcover only, but beginning with Guns at Gray Butte in 1963, more and more of books came out from Doubleday. Not all of them, but a high percentage of them, the easy explanation for this being that he probably wrote more books than Doubleday could publish.

Take 1966 for example. He wrote No God in Saguaro and Death Waited at Rialto Creek for Doubleday; The Odds Against Circle L for Ace; and Prodigal Gunfighter for Berkley. Not that year, but in the same time period, he also wrote for Lancer and Signet, the latter eventually becoming his primary publisher in paperback, both for originals and reprints of the Doubleday novels.

If you want a slim and lean western to read, one that you will pick up and not put down until you’re done, then the 128 page Prodigal Gunfighter is the book for you. Taking place in the space of only a day in the small town of Cottonwood Springs, Patten certainly doesn’t leave the reader much time to breathe.

The early morning finds the entire town down at the railroad station, waiting for the prodigal to return, in the person of the notorious home-grown gunfighter Slade Teplin. Included among them is a rather nervous deputy sheriff Johnny Yoder, who has been semi-courting Teplin’s wife, Molly, a school teacher who thought she could tame him, couldn’t, but who has not yet divorced him.

Is he the reason for Slade’s return? Slade has had no contact with Molly since he left town. His father still lives in Cottonwood Springs, but there’s hardly any love lost between the two of them. Does he want revenge of some sort against the entire town? It is pure hatred? No one seems to know, and the sense of fear in the town is everywhere.

And no one can do anything, including the law. In all but his first of many killings over the years, Slade has never drawn first. On page 91 Slade is briefly confronted by the sheriff:

… Arch said finally, “So that makes it murder doesn’t it? It’s just like a rigged poker game where you know you’re going to win because you’ve stacked the cards.”

“I always let the other guy draw first.”

“Sure. Sure you do. You can afford to. Besides, it’s smart. It gives you immunity from prosecution. But you know, every time who it is that’s going to die. Like with Cal Reeder earlier today.”

Cal Reeder was a kid, the son of a wealthy local rancher, who thought he’d make a name for himself and failed. His father is part of the story, and so are the four drifters that Johnny notices having come quietly into town.

Even at the short length the plot does not go exactly where it seems expected to do, and on pages 114-115 is one of the best choreographed fist-fights (not shoot-outs) I’ve read in quite a while, and it’s not even with Slade Teplin. He’s still on the loose, however – don’t worry about that – and with plans to cause even more havoc in Cottonwood Springs.

To show you want I mean, though, here’s at least how the end of the fight reads:

Johnny followed him over the desk-top and landed once more on top of him. The man was fighting with a silent desperation now, fighting for his life. Each blow he struck had a sodden, smacking sound both his fists and Johnny’s face were wet with blood. And he was tough. He was wiry and strong and no stranger to this kind of fight.

But he lacked one thing, one thing that Johnny had – anger, righteous indignation and outraged fury. Johnny had those things in quantity. For every blow the stranger struck, Johnny retaliated with another, harder one.

The man was weakening. They rolled against the glass-strewn floor to the window and back again. And at last Johnny felt the man go limp.

After a few seconds taken to recover, Johnny knows he needs to make the man talk. From page 116:

Johnny said softly, “You’re going to talk, you son-of-a-bitch, or I’m going to kick your head in. You understand what I said?”

He’s not bluffing. The west was a tough place to live, but Patten’s characters also seem to be tough enough themselves and equal to the challenge when they need to be. What’s more traditional than that?

PostScript: Written later in Patten’s career is a book called The Law in Cottonwood (Doubleday, 1978). In paperback form from Signet and Leisure, it eventually appears packaged up in the same edition as Prodigal Gunfighter, two novels for the price of one. I don’t happen to have a copy readily at hand, so while I’m curious and it may not be very likely, I have no idea whether or not the later book has any of the same characters as this one.

— July 2005 (slightly revised)

[UPDATE] 09-06-08. First of all, my apologies for being unable to provide a cover image for the original Berkley edition of this book. I can’t get at my copy, and I can’t locate one anywhere else. There is only one copy for sale on abebooks at the moment, for example. Early Berkley paperbacks are often hard to find, more so than you might think, but their distribution through the 1960s was extremely erratic. (Believe it or not, I was looking for them then.)

I posted this to fulfill a semi-promise I made in the previous post, in which Patten came up as an example of western noir writer. I didn’t write this review with that thought in mind, but at least from the quotes, I think you can gather that it’s a fairly tough-minded book. More than that I cannot tell you myself.

Fri 5 Sep 2008

The latest issue of the online magazine Black Horse Extra is out, devoted primarily as always the western fiction recently put out by UK publisher Robert Hale, but again, as always, branching out in many different ways.

For example, in this, the September-November 2008 issue, the main topic is an attempt to answer the question, Can western fiction also be noir?

If I’d been asked before reading this issue, except for a tendency for traditional westerns most often to have happy endings, my answer would have been yes, of course. Happily I’m reinforced in that opinion by James Reasoner’s comments about one of his current favorite western authors, Lewis Patten (1915-1981) in a review of Rope Law (Gold Medal, 1956), about which he says in part:

“… as the posse waits for nightfall so they can close in, Patten backtracks to fill in the story of what brought the characters to this point, and it’s a years-long saga of drunkenness, prostitution, robbery, and murder worthy of any of the more contemporary Gold Medal’s. Sex serves as the motivation for most of this, and while the scenes aren’t graphic, there are quite a few of them for a traditional western published in 1956.”

Chap O’Keefe (aka Keith Chapman, who leaves comments here under one or the other of each of the two names every once in a while) follows with story descriptions of several of Patten’s other books, one or two of which I’ve read myself, reviews of which I really ought to post here sometime soon. Chap points out in each of them what in his opinion makes them noir, including the imagery of the writing.

From Giant on Horseback (Ace,1964) for example; “Rain fell, gently drizzling, shining on the slicker worn by the stationmaster, dripping softly from the eaves of the weather-beaten, yellow-frame station. The train hissed patiently as it waited for the passenger to alight. . . .”

Concerning “happy endings,” James suggests that authors were constrained into doing so by editors, and Chap follows up by pointing out that editors still have great influence in that direction today.

In that regard, he goes into specific detail with a behind-the-scenes look at what his editors wanted (and didn’t want) in two of his own most recent books, A Gunfight Too Many and Misfit Lil Cleans Up, both published by Hale under their Black Horse imprint, which makes for very interesting reading.

If you’re a fan if either western or noir fiction, you’ll want to read the whole issue yourself. And I haven’t even begun to mention any of the other interviews and news items it contains. (How old is Ernest Borgnine? And what western movie is he going to be in next??)

Thu 4 Sep 2008

HERE’S FLASH CASEY. Grand National Pictures, 1938. Eric Linden, Boots Mallory, Cully Richards, Holmes Herbert, Joseph Crehan, Howard Lang. Based on the story “Return Engagement,” by George Harmon Coxe (Black Mask, March 1934). Director: Lynn Shores.

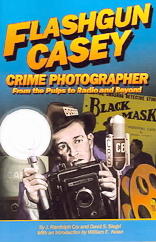

A copy of Black Mask from 1934 with “Return Engagement” in it is going to be hard to find, if you don’t already own one, but you can also find it in a much more recent book about the leading character: Flashgun Casey, Crime Photographer: From the Pulps to Radio and Beyond, by J. Randolph Cox and David S. Siegel.

I wish I had my copy at hand, because any resemblance of the Flash Casey in this movie and the Casey I remember reading other stories about is — to put it bluntly — none at all. Someone else is going to have to read it, the original story, that is, and be willing to tell us about it.

I’ve also been hard-pressed to come up with posters or stills from the film. I have one of Eric Linden, who plays Casey, and some kind of trading card of Boots Mallory, who plays Casey’s girl friend of sorts, Kay Lanning, the society page editor of the newspaper where Casey, fresh out of college, lands his first paying job. (And at $18 a week, it is not much of a job. It is a wonder what Kay sees in him.)

What you can do, however, is watch the entire movie online. Go to www.archive.org, click on the right spot, and there it is. Marvelous!

In a matter of speaking, of course. I’m talking about Internet technology, not the quality of the film. Eric Linden, whose career lasted about ten years through the 1930s, plays Casey as a naive college kid for all it’s worth, which is maybe the dime it would cost you to see it back in 1938. And if I haven’t happened to have mentioned it before, this is a comedy film all the way, so it’s not Linden who’s responsible for his actions.

What might possibly qualify this as a crime film? Almost nothing, as long as you’ve asked, but Casey does take some candid photos at a society affair that an unscrupulous gang of blackmailers alters and tries to make a bundle on. Bungling that, they kidnap Kay, and Flash comes to the rescue by commandeering an ambulance…

Besides being an actress for a short while, Patricia “Boots” Mallory was also a good-looking dancer and an actress. Her film career ended in 1938, but she had married film producer William Cagney, brother of actor James Cagney, back in 1932, well before then. She later married actor Herbert Marshall, to whom she was still wed when she died in 1958.

So, as you can see, here’s my review. Two paragraphs about the movie itself, surrounded by a lot of fluff. Go watch the movie itself and see if it deserves more.

Wed 3 Sep 2008

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

If there’s ever a biography of Ellery Queen—not of the detective character but of the cousins Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee who created Ellery and also used his name as their joint byline—the following incident from Fred’s life deserves to be included.

The first part comes mainly from one of the long introductions that he wrote for each story published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine during its early years; the follow-up was unearthed by radio historian Martin Grams, Jr. and will appear in one of his forthcoming books.

In the spring of 1946, soon after being discharged from the Army at the end of World War II, Dashiell Hammett arranged with “a certain school of social science in New York City” to offer a Thursday evening course on mystery fiction aimed at writers and writer wannabees.

At this time Fred’s main tasks in life were keeping EQMM afloat and, after his wife’s death from cancer, raising two young sons. He read the announcement of Hammett’s course and was impelled by curiosity to attend the first session, on May 2.

Hammett invited him on the spot to co-teach the course and Fred agreed, each two-hour stint followed by “all-night bull-and-brandy sessions” between those giants of crime fiction. At the end of the May 16 class a young woman named Hazel Hills Berrien approached Fred and offered him the manuscript of a story she had begun writing after the first session.

Fred, as always, suggested certain changes — “in the character of the detective, in the plot construction, and in the title,” he said later—but when they were made to his satisfaction, he bought the tale, which appeared in EQMM for September 1946 as “The Unlocked Room” by Hazel Hills.

Then as now, magazines appeared on the stands some time before the publication month listed on their front covers, and the September EQMM had been available at least for a few weeks before August 31, 1946. That evening’s episode of the popular ABC radio series The Green Hornet was called “Death in the Dar” and dealt with a civil servant accused of embezzlement who is found shot to death in a room with the door locked and the window bolted. Newspaper publisher Britt Reid, a.k.a. the Green Hornet, rejects the obvious theory of suicide and eventually proves that the man was murdered.

Hazel Hills Berrien wrote ABC four days after the broadcast, admitting that she hadn’t heard the episode but claiming she’d been told by a friend that it “bore a peculiar resemblance to a recently published short story of mine.”

In this and several subsequent letters, each more threatening than the last, she demanded a copy of Dan Beattie’s script but refused to send ABC’s lawyers a copy of her story.

Eventually Fred heard of the dispute and, on October 11, wrote to Green Hornet creator George W. Trendle, promising a copy of September’s EQMM and asking in return for a copy of Beattie’s script.

Four days later and after reading “The Unlocked Room,” Trendle replied to Fred, rejecting any allegation of plagiarism but saying: “[H]ad Miss Hills handled the matter as diplomatically as you have, I think a copy of our script would have been in her hands long ago.”

A later letter to Fred from Green Hornet attorney Raymond Meurer made the same point: “[W]e regret that the matter was handled so clumsily by Miss Hills…. [H]ad we received the request originally from you, we would not have hesitated a moment in supplying the script.” The tempest in a teapot quickly blew away since the only similarity between Hills’ story and the Hornet script was that both involved a murder in a locked room with a gimmicked window.

As far as I know Hills never wrote another story, certainly none published in EQMM.

Among the reprints in the EQMM issue that contained Hills’ story was one by Agatha Christie (“Strange Jest,” a Miss Marple tale originally published in 1941), again with an introduction by Fred Dannay, this one quoting a stanza from one of Christie’s poems.

It comes from “In the Dispensary,” which was included in her collection The Road of Dreams (Bles, 1925):

From the Borgias’ time to the present day, their power

has been proved and tried:

Monkshood blue, called aconite, and the deadly cyanide.

Here is sleep and solace and soothing of pain—

courage and vigour new;

Here is menace and murder and sudden death—in these

phials of green and blue.

Okay, so it’s doggerel. Thanks anyway, Fred, for giving me this item for my column’s Poetry Corner more than sixty years ago!

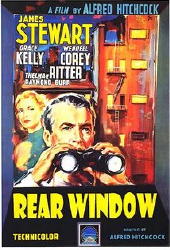

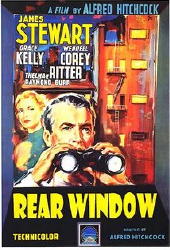

John Michael Hayes (1919-2007) never wrote a mystery novel or short story but, thanks mainly to his screenplays for several Alfred Hitchcock films, most notably Rear Window (1954) and the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), his memory remains green for us.

I recently had occasion to read a deposition Hayes gave in August 1991 in connection with some litigation over Rear Window and was delighted to find some information about Hitchcock’s connection with Cornell Woolrich that I believe has never appeared in print.

Among the six tales brought together in the second collection of Woolrich’s short fiction (After-Dinner Story, as by William Irish, 1944) were “Rear Window” (first published under Woolrich’s own name in Dime Detective, February 1942, as “It Had To Be Murder””) and “The Night Reveals” (first published in Story Magazine for April 1936).

Hitchcock was interested in both. Shortly after Hayes began working on the Rear Window screenplay, “Hitch asked me…if I would read [“The Night Reveals”] and comment on it because he had [had] a choice between the two stories and wanted to know if he’d made the right choice. And I said he certainly had because “Rear Window” lent itself to intense suspense material and intense personal relationships which the other story didn’t.”

Still and all, “The Night Reveals” is also marked by powerful suspense scenes and an intense relationship—between insurance investigator Harry Jordan and his wife, who he comes to suspect is a compulsive pyromaniac—and it’s a shame Hitchcock didn’t at least use it as source for an episode of his TV series. Preferably one directed by himself.

Tue 2 Sep 2008

I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but most of the recent posts, going back over the past month now, have not been newly written by me. Looking back through what appeared here in August, there were 34 posts, and only about a third of them consisted of new stuff from me. (Some of the reviews came from my “archives,” of course, and for the reviews written by others I’ve continued to add cover images, bibliographic data and so on, so it wasn’t as though I wasn’t doing anything.)

I watched and reported on six movies, which isn’t bad, but what’s really frustrating is that I read only five books all month. You can go back, read the reviews and count them for yourself.

This is an abysmal record. Even on a slow day I can go to Borders and buy twice that many without half trying. And I go maybe three times a week. (Not to mention books I order online from ABE, Amazon and Biblio.com.)

What’s even worse, and so far I still haven’t been able to do anything about it, is the stack of unanswered email that stacking up on my computer. My apologies to everyone who’s still waiting patiently for a reply to something that you’ve sent me this month — a question, a piece of information, a comment about a blog post — if I answer immediately, you hear from me. Otherwise maybe you haven’t.

But believe me, it’s just as frustrating on this end as I assume it is on yours.

After I returned from Pulpcon at the beginning of August, my new endocrinologist started me on a new regime of medications, and to put it frankly, it just isn’t working. Worse, it’s hard to put any confidence in doctors who look at the blood tests and suggest doing new things without first asking how you’re feeling, even when they’re meeting you for the first time.

It’s all trial and error, and so far, it’s mostly error.

I hope I don’t have cut back on my own participation on this blog any further, but just in case, as I hope you have noticed, I have a lot of friends and other sources to help cover for me.

And if you are waiting to hear back from me about something, I hope you can be patient a while longer. (I mentioned sharp pointed objects a while ago, in case I could use a nudge. They’re not needed yet, but maybe you should keep them handy, just in case.)

Mon 1 Sep 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Bill Pronzini:

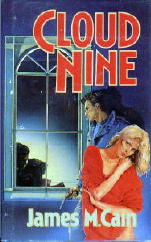

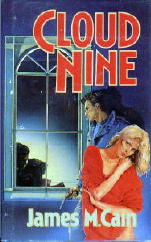

JAMES M. CAIN – Cloud Nine. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1984; paperback, 1987. Robert Hale, UK, hardcover, 1985. J. M. Dent & Sons, Canada, trade ppbk, 1987 (shown).

In the 1930s and 1940s, James M. Cain was the most talked-about writer in America. His novels of that period, like the detective novels of Dashiell Hammett, a few years earlier, broke new ground in crime fiction.

Until the publication of The Postman Always Rings Twice in 1934, sex was a topic handled with kid gloves and almost always peripheral to the central story line; Cain made sex the primary motivating force of his fiction, and presented it to his readers frankly, at times steamily. (Some of the scenes in Postman are downright erotic even by today’s standards.)

But Cain, of course, was much more than a purveyor of eroticism. His lean, hard-edged prose caused critics to label him a “hard-boiled” writer, but he is much more than that, too. His best works are masterful studies of average people caught up and often destroyed by passion (adultery, incest, hatred, greed, lust). They are also sharp, clear portraits of the times and places in which they were written, especially California in the depression era Thirties.

Cain’s success began to wane in the Fifties and Sixties, however, partly because of a desire to write novels of a different sort from those that had brought him fame, and partly because of a clear erosion of his talents (a seminal fear of all writers) brought about by advancing age.

Cloud Nine is one of those “different” novels, written in the late 1960s when Cain was seventy-five. It was rejected by his publisher at that time and shelved. Resurrected for publication in 1984, seven years after Cain’s death, it was puffed by its publisher as “an important addition in contemporary American literature” and by an advance reviewer as “a minor masterpeice and publishing event of some note.”

It is none of those things. It is, simply and sadly, a flawed novel of mediocre quality – a pale shadow of his early triumphs.

The novel’s basic premise is solid. A teenage girl, Sonya Lang, comes to Maryland real-estate agent Graham Kirby with the news that his nasty half brother, Burwell, has raped her and that she is pregnant as a result. Through a complicated set of circumstances, Graham agrees to marry Sonya, initially for charitable reasons; but he soon falls in love with her.

He then discovers that Burwell may be a murderer as well as a rapist, and that another murder may be part of Burwell’s future plans. The conflict between Burwell and Graham forms the central tension here, with Sonya as one catalyst and a million dollars in prime real estate as another.

All the elements are present for a classic Cain novel, ones that should combine to keep the reader on tenterhooks, “anxious to find out what happens,” as Cain biographer Roy Hoopes says in an Afterword, “but always dreading the ending because of the horror [he senses] would be waiting – ‘the wish that comes true’ that Cain said most of his novels were about.”

But the elements simply don’t mesh. The bulk of the novel is taken up with the relationship (much of it sexual) between Graham and Sonya, to the exclusion of everything else; Burwell doesn’t even appear on stage until page 108, and other major plot points are introduced sketchily and/or not developed until the final fifty to sixty pages.

Graham is a rather dull and unappealing narrator, not at all one of “those wonderful, seedy, lousy no-goods that you have always understood,” as one of Cain’s friends described the protagonists of Postman and Double Indemnity.

And the prose is anything but lean and hard-edged. It reads as if Cain, late in life, discovered and became enamoured of commas and clauses, as witness the novel’s opening sentence: “I first met her, this girl that I married a few days later, and that the papers have crucified under the pretense of glorification, on a Friday morning in June, on the parking lot by the Patuxent Building, that my office is in.”

Not everything about Cloud Nine is weak; there are some crisp passages of dialogue reminiscent of vintage Cain, the character of Sonya is well developed, and there is power in the climactic scenes (although none of the existential terror and tragedy of the early books). But on balance, and like the other suspense novels Cain wrote late in life – The Magician’s Wife (1965), Rainbow’s End (1975), The Institute (1976) – it is minor and disappointing.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust

« Previous Page