March 2009

Monthly Archive

Tue 17 Mar 2009

THE CURMUDGEON IN THE CORNER

by William R. Loeser

L. A. G. STRONG – All Fall Down. Collins Crime Club, UK, hc, 1944. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hc, 1944 (shown). Canadian paperback: White Circle #221, 1945.

All Fall Down is much the same kind of book [as Death and the Night Watches, by Vicars Bell, reviewed here earlier] and even better.

[That book was described, in part, as “another of that enjoyable sub-genre, the English village murder, chock-a-block with well-distinguished local characters.”]

Inspector Ellis McKay has just finished a difficult case, so his friend, used-bookseller Paul Gilkison, takes him with him to appraise the library of Matthew Baildon, bibliophile and domestic tyrant.

Unfortunately, before they are well-started, someone assists Baildon’s overloaded bookshelves in collapsing on his head. McKay takes over the investigation and proves himself to be, in addition to a bookworm, a trencherman, happy napper, and composer, as well as a shrewd judge of human nature.

Here the brow-beaten woman is the wife and the daughter’s hope for escape the university, not marriage. But these two have a wonderful auntie to comfort them, and the girl has two tutors competing for the chance to improve her mind — an excessively-healthy male with an invalid wife and a female with the need to dramatize her humdrum life. Turns out [deleted] did it, but the unlikeliness of this after years of abjection did not spoil my pleasure in what went before.

In this case, McKay becomes friends with his local counterpart, Inspector Broadstreet, with whom he has later adventures that I’m looking forward to reading.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 4, July-Aug 1979 (slightly bowdlerized).

Bibliographic data. Strong’s entry in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, includes five novels and five short story collections. Inspector McKay appears in four of the novels. Of these, the ones in which Inspector Broadstreet also appears, as Bill suggests, is unfortunately not noted. Of the author himself, L. A. G. Strong was born in 1896, and he passed away in 1958. Al Hubin also says: “Born in Plympton; educated at Brighton College and Oxford; author, editor, journalist, and reviewer; Assistant Master at Oxford.”

McKAY, INSP. (Chief Insp.) ELLIS [L. A. G. Strong]

All Fall Down (n.) Collins, 1944.

Othello’s Occupation (n.) Collins, 1945. US title: Murder Plays an Ugly Scene. Doubleday, 1945.

Which I Never (n.) Collins, 1950.

Treason in the Egg (n.) Collins, 1958.

Mon 16 Mar 2009

A Movie Review by MIKE TOONEY:

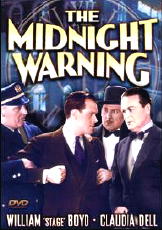

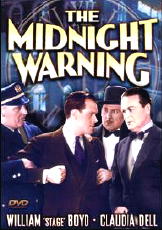

THE MIDNIGHT WARNING. Mayfair Pictures, 1932. Also released as Eyes of Mystery. William [Stage] Boyd, Claudia Dell, Huntley Gordon, Johnny Harron, Hooper Atchley. Director: Spencer Gordon Bennet.

An oddball detective film that may have been inspired by an actual event, The Midnight Warning stars William “Stage” Boyd as detective Bill Cornish investigating a disappearance: an ailing young man who had just recently checked into a hotel with his sister.

She has to travel to Utah on urgent business, but when she returns her brother has vanished and absolutely everyone claims not to remember him (even though we, the audience, know better).

So obviously there’s a cover-up — but why? The solution for me (which I will not reveal) was not very satisfactory, when one considers all the nicely-wrought mystification that precedes the denouement.

Even odder, at this late remove from historical events, are the reasons given — an economic upturn in the Depression being chief among them. (The recent election of FDR seems to have led people, among them Hollywood writers, to believe mistakenly that happy times were here again — and yes, that is germane to the film’s plot.)

Not only is this an oddball movie but also the detective himself is slightly off kilter: Instead of the usual hardboiled, self-assertive personality type, Cornish is more than willing to push others into compromising and even potentially dangerous situations, at one point getting a friend to act as a cats-paw. Despite all that, however, he still comes across as something of an amiable antihero.

There is a nod to Sherlock Holmes when, early in the film, someone takes long range shots at a character through a window — indeed, he is wounded without realizing how it happened. Detective Cornish then sets a trap using a mannequin to pin down the shooter’s location.

Later films took up the theme of someone vanishing from crowded areas: So Long at the Fair (1950) and Dangerous Crossing (1953). (The latter is based on a radio play, “Cabin B-13,” by John Dickson Carr.)

The Midnight Warning is an engrossing little mystery with a great buildup but a disappointing reveal. It’s available on DVD from Amazon.com for about eight dollars.

Sun 15 Mar 2009

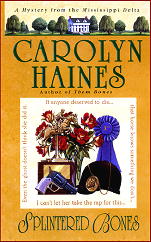

CAROLYN HAINES – Splintered Bones. Dell, paperback reprint: February 2003. Hardcover edition: Delacorte, February 2002.

There’s a huge difference between mysteries like the recent pair of “Golden Age” novels by G. D. H. and Margaret Cole I reviewed recently, especially the latter, and this one, and that’s the amount of personal life of the detective we get to become a part of.

Sarah Booth Delaney is trying to make a go of it as a private investigator, and as a former pampered Daddy’s Girl, southern-belle Mississippi-Delta style, she hasn’t quite succeeded in getting her own life on track — and she has a ghost in her house who keeps telling her that. (Sarah Booth is on the wrong side of thirty, not married, and she has no viable prospects in sight.)

This, her third major case, seems to come straight from a Dixie Chicks’ country song. You may know the one. The dead man was a wife abuser, a lousy father, and has been compulsively piling up gambling debts. He’s all-around No Good. No one has a decent word to say about him. His wife Lee has confessed. Her only defense is that Kemper Fuquar deserved to die, and she hires Sarah Booth to help her prove it.

Part of the deal is taking in Lee’s sullen 14-year-old daughter Kip, who proves to be the heart of the matter, in more ways than one. A teenager in her home? It proves to be just what Sarah Booth’s heritage and home, Dahlia House, needs.

Kip may also be the reason for her mother’s confession, which serves to complicate matters, and she’s just one of the fine characters Carolyn Haines gives us a sharp, keen insight into. But the over 350 pages of small print are also filled with a meandering investigation, and the facts seem awfully mushy. (If the right questions were asked at the right time, and of the right people, the book could easily have been 100 pages shorter.)

And when tragedy strikes again, Sarah Booth’s reactions are surprisingly flat, along with everyone else’s. Are they suddenly all on Prozac? For all but these few pages, the inhabitants of the small southern town of Zinnia are filled with a zingy zest for life, and the singular lack of a more emotional response to this remarkable night of misadventure just doesn’t ring true.

The book’s well worth reading, in other words, but the recommendation comes with some small little warning flags as well. Adjust to your own tastes and preferences.

— February 2003

Bibliographic Data: The Sarah Booth Delaney Mysteries. For full coverage of all of Carolyn Haines’ work, both fiction and non-fiction, visit both her website and a very good external one, located here.

Them Bones. Bantam, pb, Nov 1999.

Buried Bones. Bantam, pb, Oct 2000.

Splintered Bones. Delacorte, hc, Feb 2002; Dell, pb, Feb 2003.

Crossed Bones. Delacorte, hc, April 2003; Dell, pb, Feb 2004.

Hallowed Bones. Delacorte, hc, March 2004; Dell, pb, Jan 2005.

Bones to Pick. Kensington, hc, July 2006; pb, June 2007.

Ham Bones. Kensington, hc, July 2007; pb, June 2008.

Wishbones. St. Martin’s, hc, June 2008; pb, June 2009.

Greedy Bones. St. Martin’s, hc, July 2009.

Sat 14 Mar 2009

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Heads You Lose. John Lane/The Bodley Head, UK, hc, 1941. US hardcover: Dodd Mead, 1942. Hardcover reprint: Ian Henry (UK), 1981. Paperback reprints include: Penguin (UK), several printings, 1950s; Bantam, June 1988 (shown).

Christianna Brand’s mystery output seems paltry compared to, say, Agatha Christie.

In the 1950s, Brand produced progressively less in the crime fiction field, focusing more on her children’s writing. According to the IMDb, a handful of her children’s stories were adapted for British TV and one was the subject of a full-length motion picture a few years ago.

Film makers gave her mystery fiction brief attention in the mid-to-late 1940s, and then she was promptly forgotten. Only Green for Danger (1946), based on her 1944 novel, seems to have been given a proper treatment. Film critic William K. Everson and yours truly agree that this movie is THE classic detective film, with The Kennel Murder Case vying with it for first place.

Thomas Godfrey, in his English Country House Murders (1989), characterizes our author and her writing thus: “Christianna Brand (Mary Christianna Milne Lewis), the last of the grandes dames of traditional English writing, was, like Josephine Tey, a connoisseur’s writer. Her plots are intelligently premeditated, rich in atmosphere, keenly observed, and subtly set forth.” (page 423)

Heads You Lose memorably introduces her series sleuth, Inspector Cockrill, like this:

“[He] was a little brown man who seemed much older than he actually was, with deep-set eyes beneath a fine broad brow, an aquiline nose and a mop of fluffy white hair fringing a magnificent head. He wore his soft felt hat set sideways, as though he would at any moment break out into an amateur rendering of ‘Napoleon’s Farewell to his Troops’; and he was known to Torrington and in all its surrounding villages as Cockie. He was widely advertised as having a heart of gold beneath his irascible exterior; but there were those who said bitterly that the heart was so infinitesimal and you had to dig so deep down to get to it, that it was hardly worth the trouble. The fingers of his right hand were so stained with nicotine as to appear to be tipped with wood.” (page 22)

Heads You Lose was, according to the bibliographies, Christianna Brand’s second book; and there are some rough places in the narrative that seem to show she isn’t quite as accomplished as she would later become. Nonetheless, compared to some other Golden Age writers of the same period, she often reads like Shakespeare.

Chapter 6, the coroner’s inquest, is a marvelous set piece filled with low comedy and not a little misdirection.

It isn’t revealing too much to say that Inspector Cockrill doesn’t really solve this case; he lets the other characters eliminate false trails on their own. It’s fun to watch one indolent character exerting himself trying to prove the guilt of another character — but what’s his motivation, to protect a woman or to shift suspicion from himself?

Cockie also spends a large part of the first half of the book off-stage and gradually assumes a greater presence later; also, we are allowed into his thoughts only intermittently — in fact we spend much of the book inside various other characters’ minds, including, believe it or not, the murderer’s (but without being conscious of it).

The story has a historical setting, a cosy English village not long after the Dunkirk evacuation, but the war is alluded to only in several places and never intrudes much into the narrative.

It’s annoying when Brand introduces an impossible crime but doesn’t do much with it — the impossibility is later dismissed in one sentence. But all the characters, major and minor, are well imagined.

Once she had hit her stride, Christianna Brand could play “The Grandest Game” with the best of them. Heads You Lose shows her warming up for her later, more solidly plotted novels in which she could often out-Christie Christie.

Sat 14 Mar 2009

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

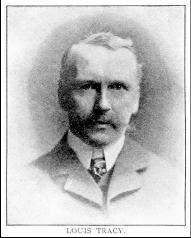

LOUIS TRACY – The Strange Case of Mortimer Fenley. Edward J. Clode, US, hardcover, 1919. Serialized in the Boston Sunday Globe Magazine, May 30 to July 25, 1920. Previously published in the UK as The Case of Mortimer Fenley: Cassell & Co., hardcover, 1915.

Artist John Trenholme is staying in the Hertfordshire village of Roxton, having gone there at the request of a magazine to do paintings of the local area before the railway arrives and ruins everything.

His request to thus immortalise a nearby Elizabethan mansion is rebuffed by its owner, Mortimer Fenley, private banker and father of two half-brothers.

Trenholme finds out there’s a public right of way across Fenley’s parkland and on a lovely June morning he avails himself of it to paint the view — which includes a young woman in a bathing suit taking a morning dip in the lake. He is thus on the spot to hear the shot that kills Fenley on his own doorstep.

At this point one of my favourite sleuthing teams, Superintendent James Leander Winter and Detective Inspector Charles Francois Furneaux, arrive on stage when Scotland Yard is called in by oldest son Hilton Fenley. To add to the family’s troubles, both siblings wish to marry their father’s beautiful ward Sylvia Manning — she of the bathing suit — which worsens the already bad blood between them.

The younger son Robert is a ne’er-do-well who was in London when his father died, or was he? Could the murder be connected to a bond robbery at the Fenley Bank? How was the seemingly impossible crime committed when a prime suspect was known to be in the house when the murderous shot was fired from a wood some 400 yards away?

My verdict: Much as I have enjoyed the Winter & Furneaux stories, I must mark this one as a B. The Fenleys are curiously thin as characters, and I felt the lesser players in the drama were more rounded out, probably because Tracy provides a different angle for the traditional supporting cast.

Thus for example we have the oft bibulous butler depicted instead as a wine connoisseur and the village bobby as intelligent and quick thinking. On the other hand, the touch of melodrama towards the end of the novel seems somewhat out of place, and prospective readers should be aware there are a few comments of an un-PC nature.

Etext: http://www.munseys.com/diskseven/mofendex.htm

Bibliographic data: John D. Squires’ long chronological checklist for Louis Tracy (1863-1928), aka Gordon Holmes and Robert Fraser, is online here here.

Fri 13 Mar 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors[4] Comments

David Vineyard wrote this in response to Bill Pronzini’s

1001 Midnights review of

Knife in the Dark, by G. D. H. and Margaret Cole, in which it was pointed out that G. D. H. Cole was a noted social and economic historian as well as one half of a pretty good writing team. Patti Abbott picked up on this, and I added that Father Ronald Knox was another author who was certainly known for writing more than mysteries. Here from David are a good many others. — Steve

The non-writing careers of writers is always fascinating, and not just those like Dick Francis, Dashiell Hammett, Ian Fleming, John Le Carre, Joseph Waumbaugh, Joe Gores, Erle Stanley Gardner, or Graham Greene whose work is reflected in their writing (in order, jockey, private detective, journalist/spy, diplomat/spy, policeman, private detective, lawyer, and journalist/spy).

Rex Stout was a millionaire before he was 22 for designing a system of accounting for public schools in Wisconsin, had a long career as a pulp writer, wrote a novel compared to Philip Wylie and F. Scott Fitzgerald (How Like a God), and then at 40 created Nero Wolfe. Raymond Chandler was an oil exec until the Depression hit and then turned to writing at 45. Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote Tarzan on the back of the letterhead stationary for his bankrupt haberdashery when he was thirty-nine after a career of differing jobs including fighting Geronimo in the cavalry.

Agatha Christie was a nurse in WWI in charge of the poisons cabinet (which she became an expert on) and P.D. James a nursing administrator. Sax Rohmer and P. G. Wodehouse (best friends) were both clerks at the same bank in Alexandria Egypt — where later C. S. Forester (Horatio Hornblower) and Geoffrey Household briefly worked.

Conan Doyle was an optometrist (though never a succesful one) and Margery Allingham came from a family of pulp writers who filled the pages of the countless Boys’ Own Paper type publications in England, writing everything from Robin Hood and Billy Bunter to Sexton Blake. Leslie Charteris was a failed cartoonist — ironic in that he ended up writing Secret Agent X-9 and The Saint strips.

During WWII Eric Ambler was John Huston’s cameraman in Italy on the Oscar winning Battle of San Pietro, and Max Brand died in Italy while working as a war correspondent.

John Buchan topped almost everyone. After a distinguished career in many important political roles he was Governor-General of Canada in the critical years before WWII — often credited with healing the rift between Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King and London and deepening the alliance between Canada and the US (and if you think that is overstating his importance, even Winston Churchill gave him credit for insuring Canada stayed in the Commonwealth and supported England in the war).

In his real life S. S. Van Dine (Willard Huntington Wright) was a distinguished art critic. A. E. W. Mason was a secret agent for the British Admiralty whose pre-WWI network in Spain operated as the primary Allied network in that country well into the Cold War and who once foiled an almost Bondian biological warfare plot to smuggle anthrax infected animals into the Allies stock in WWI.

Edmund Crispin was conductor/ composer Robert Montgomery, who wrote the film scores for the Carry On films among others. Mystery writer Laurence Payne starred on stage and film (The Crawling Eye …) and played Sexton Blake on BBC television for years. Alan Cailliou, who wrote numerous suspense and adventure novels, was a familiar character actor in films and television.

Twenties and thirties adventure, mystery writer Achmed Abdullah was not only the son of a Romanov Prince and an Indian Queen, but spent a lifetime as an officer in the British Army. Talbot Mundy was a con-man before an illness reformed him and he turned to writing, and German writer Karl May was born blind, regained his sight, became a criminal, and reformed to become a beloved storyteller loved by Einstein, Herman Hesse, and Albert Schweitzer (and alas also Hitler) — and responsible for all those Winnetou movies with Stewart Granger and Lex Barker that in turn inspired the Spagetti Western — so he may not be all that innocent or reformed.

Zane Gray was a dentist, John Gardner an ex-SAS special forces op and leftist reverend, Van Wyck Mason an army engineer for twenty years before he created Colonel Hugh North, and Elizabeth Peters/Barbara Michaels is really distinguished Eyptologist Barbara Mertz.

Edgar Wallace, aside from being a journalist, was a race track tout, Peter Cheyney a secretary for Oswald Mosely’s fascist Black Shirts in England (briefly and before Mosely turned from nut to traitor), and Gerard Fairlie, aside from being the real life model for Bulldog Drummond, was a member of the Royal House Hold cavalry and favorite of the Queen.

John Mortimer the author of the Rumpole mysteries was the barrister who won the landmark Crown vs Lady Chatterly’s Lover case in the early sixites that broke the back of censorship in British publishing. John B. West, author of the Spillane-ish Rocky Steele books, was a West African doctor in general practice.

Techno thriller writer Tom Clancy was an actuarial table expert for the insurance industry, and current bestseller James Rollins a veternarian. Michael Innes was an Oxford don (J.I.M. Stewart) and prolific John Creasey created his own political party and stood for office.

A few are even fitting, Donald MacKenzie (Nowhere to Run) who wrote about reformed thieves and John Raven, a retired Special Branch officer who lived on a houseboat on the Thames, was himself, a reformed thief. Solicitors Michael Gilbert and John Welcome were literary agents to Raymond Chandler and Dick Francis respectively.

The late Michael Crichton began his career writing under the pseudonyms John Lange and Jeffrey Hudson so he wouldn’t be thrown out of medical school for moonlighting. Western historical novelist Will Henry wrote cartoons for MGM with Tex Avery as Heck Allen. Douglas Preston of the bestselling team of Preston and Lincoln Childs worked for the Museum of Natural History in New York.

Brett Halliday and Jim Thompson were both oilfield roughnecks. William Henry Porter, or O. Henry, was a convicted embezzler who began telling stories while serving in Sing Sing. W. Somerset Maugham was a medical student who began writing for the extra money. Jeffrey Archer reversed the process, beginning as a writer and now an ex politician and convicted felon.

Pulpster Walter Gibson was a PR man for Harry Houdini and Norvell Page, author of the Spider, gave up writing to work for the government during WWII eventually becoming secretary to the postwar Hoover Commission and an official in the Atomic Energy Commission (and if the author of the Spider, who used to go out on the beach in Miami dressed in a slouch hat a black cloak, working for the A.E.C. doesn’t make you uneasy, nothing will). Nicholas Boving, who writes the Maxim Gunn thrillers, currently was a mining engineer who used to traipse around the world from Africa to Western Australia.

The fact is writers come from a variety of backgrounds — and sometimes a name that we are only familiar with in terms of our leisure reading will have a completely different connotation to others in another field. For example Nicholas Blake often mentioned here as one of the icons of the golden age of the detective story (which he was) was also C. Day Lewis, the father of actor Daniel Day Lewis, and Poet Laureate of England. Sort of puts his detective writing career in perspective.

Wed 11 Mar 2009

Sylvia Orman was my wife Judy’s mother, and she died this morning around 9 am.

She was 96 years old. Every year you expect there will be another birthday, but this year there won’t be. We never lost hope, but when you’re that age and small problems begin, they start to add up quickly. She’d had a pacemaker installed about three weeks ago and was doing well in physical therapy until she got a viral infection which turned to pneumonia, and she had to return to the hospital.

We saw her yesterday afternoon, which is when we said our last goodbyes. She was heavily sedated but she squeezed Judy’s hand when she talked to her, so we think she knew we were there.

We’re sad today, of course, and still shaken up a little, but we’re glad that we had her living close by for so long. She lived in an assisted living facility, but until the end she was very independent and did everything pretty much on her own.

Did the usual mother-in-law jokes apply? Not once. Not ever.

Tue 10 Mar 2009

I hope everyone has been following the long discussion that the most preceding post has developed into, especially if you’re interested in film noir, or even if you’re not. It will be a while longer, I’m sorry to say, before this blog gets back to its normal coverage of books as well as movies, but here’s a question that occurred to me after reading through the previous group of comments again.

In discussing which movies are noir and which are not, both Walker Martin and David Vineyard (primarily, but not exclusively) have brought up a long long list of films to use as examples. Everyone knows which movies are noir and which are not — it’s all the in-betweener’s that cause the problems, no matter what definition you use.

Here’s the problem. Reading through the comments, I’ve been adding movies to my “must see” list left and right, whether they’re noir or not. They all sound worth watching, but how? I’ve read somewhere that only 4% of the movies ever made are commercially available.

And every time a new format comes along, more and more movies are left behind. From VHS to DVD, some movies didn’t make the upgrade. Now it’s DVD to Blue-Ray, and only those deemed most commercially advantageous will make that step up — and those generally seem to be recent movies in which I personally have little interest.

Next, I presume, will be digital downloads, which in terms of commercial releases in cleaned-up editions, will probably bypass even more films not worth the attention of the giant conglomerates. Which leaves it to collectors and the underground market to keep many many old (and even recent) movies available for watching. For me, I’m going to stop with DVDs. No further upgrades for me.

Which makes for a long preamble to my actual question. As Walker and David have pointed out, there are many books on Film Noir which list many films as being noir as well as many others deemed marginal. If you go to Amazon or similar sources, you won’t find them all, but if you were to go to ioffer.com or sell.com, many if not most of them do turn up — but not all.

Here’s my question, directed primarily to Walker and David, but anyone else can jump in. What movies are there — and let’s stick to noir foremost, but why not include any crime movie — might you have been looking for and have not yet found a surviving copy to obtain on DVD as your own?

What are the most wished-for crime films, ones that you’d most like to see, in other words, but so far don’t seem to exist, even as collectors-only copies?

Thu 5 Mar 2009

Part One of this ongoing discussion appeared

here. This comment left by David Vineyard earlier today was #17 for that post, and I’ve deemed it substantial enough to appear on its own.

I’ll continue to be occupied with a host of other matters this week and next, so images will be added later, as I can get to them. For now it’s the text that matters, and from this point on, David has the floor. — Steve

I’m going to go out on a limb here and say why I don’t think some films embraced as noir really belong there, then saw it off behind me by trying to define what noir is. But first the films that I don’t think really are noir despite having noir elements.

I’ve already explained why I don’t think The Maltese Falcon is noir — Spade is hardly alienated, doomed, obsessed or the victim of mysterious forces. He’s in control of himself and the situation, and the closest he comes to a touch of noir is a pang of regret at sending Brigid up the river for killing Archer. The only bad nights Spade is going to have is getting Miles Archer’s widow off his neck.

Laura is a bit more problematic, because the sleuth is briefly obsessed, but in the end he isn’t a noir protagonist either. Clifton Webb’s villain is alienated and obsessed, but in noir it’s the hero and not the villain that counts.

I Wake Up Screaming would be noir if Laird Cregar’s cop was the hero, but the hero and heroine are PR man Victor Mature and showgirl Betty Grable, and if you remove the murder plot, the two would be perfectly served in a musical (in fact, they were).

Johnny Eager is a slick MGM take on a Warner’s gangster movie, but again the hero, Robert Taylor isn’t a noir hero (his buddy Van Heflin is though, but that doesn’t count). There is nothing in Johnny Eager’s character different than the general run of gangsters in a hundred similar films.

All of these films use the shadows and high contrast lighting of noir, but then so does the swashbuckler The Sea Hawk. They all have noir elements, but they lack the core elements that define noir. For that matter I would put Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt as only borderline noir (Teresa Wright is neither alienated, obsessed, nor beset by mysterious forces — she’s Nancy Drew caught in an adult mystery).

Shanghai Gesture is an old fashioned German Expressionist melodrama, and not a noir though a contributor to the genre. An argument can be made however for You Only Live Once, Street of Chance, Mask of Dimitrios, The Stranger on the Third Floor, and Journey Into Fear.

I’ll give them their points, and only point out that two of them are spy films and by that nature share elements with noir, and the two spy films are directed by Noir director Jean Negulesco and Orson Welles (though credited to Norman Foster). The elements of distrust, paranoia, and betrayal common to most spy films are noirish to begin with.

But then what is noir? We’ve beat around the noir bush and come up with some general ideas — as Walker Martin points out it is a style — but it isn’t just a style, or every moody horror film would be noir, so I’m going to try to break down some key elements that I think define noir.

First of all noir is defined by the protagonist, and the noir protagonist has some distinct characteristics. As often as not he’s a veteran who is having a tough time adjusting to the peace time world, but veteran or not he is always alienated in some way.

In noir this means he is lost in a darkness he carries inside of him, but which is expressed by the world outside of him. He is inevitably an urban figure, usually in an urban setting (but even in a rural setting — On Dangerous Ground, Un roi sans divertissement — the hero is an urban figure).

Above all he is opposed by a “mysterious force,” a situation or antagonist beyond his control which leaves him with a sense of fear, powerlessness, and isolation. He is faced with forces of chaos he can’t control and sometimes is even attracted to. The noir hero is at the mercy of forces he can’t control and can only hope to survive.

The second factor key to most — but not all — noir is obsession. The noir protagonist is invariably obsessed — with the truth, revenge, a woman, power, money, or an impossible dream. He carries that obsession to the point it nearly (or does) destroy him (these definitions all define the female protagonists of noir as well).

He is set apart by the obsession, and though he recognises the power it has over him he can’t escape. That inability to escape from one’s fate is another key element of noir. You can run from everything but yourself.

Noir style is also important. High contrast lighting gives objects a certain sinister feel. Traffic lights, street lights, rain-soaked streets, narrow alleys, dark stairwells in cheap apartments, abandoned buildings, fire escapes, the sewers beneath the city, darkened warehouses — all these places and things take on a character of their own.

The freighter where the final scene of Anthony Mann’s T-Men takes place, the bridge girders Arturo De Cordova flees onto in The Naked City, the tunnels beneath Union Station, the sewers of LA in He Walked by Night, the refineries in White Heat and Follow Me Quietly, the merry-go-round in Strangers on a Train, the office stairwell in Mirage‘s blackout, the bleak snowbound countryside in On Dangerous Ground and Murder Is My Beat, the baseball stadium in Experiment in Terror, the inner works of the Big Clock, the elaborate garden in Night Has 1000 Eyes, the claustrophobic corridors of the train in Narrow Margin, and the carnival fireworks of The Bribe are all as much characters in the film as any human. They are familiar and alien at the same time.

In their book Film Noir (Overlook Press, 1979), Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward write that Noir “consistently evokes the dark side of the American persona … a stylised vision of itself, a true cultural reflection of the mental dysfunction of a nation uncertain of transition.” They put the classical noir period between the end of WWII and the end of the Korean Conflict when the country is in transition from the war and the influx of returning veterans adjusting to civilian life — and setting off the baby boom.

Among the other staples of noir is the femme fatale. She is hardly new to literature (lest we forget Delilah or Madame De Winter), but the noir protagonist is uniquely unable to resist or recognise her (Sam Spade on the other hand, not only recognises her, but plays her and ultimately disposes of her).

To this sexual confusion is added an atmosphere of violence, paranoia, and threat. The hero is vulnerable and beset by grotesque characters that seem to come out of a horror film at times (in The Big Clock Charles Laughton is shot in closeup with a wide angle lens that further distorts his already magnificently ugly features). Many of the characters in noir would be at home in Paris Grand Guignol or Dicken’s novels.

Certain visual cues are important, high contrast lighting, shadows, disorienting angles, and the sudden threat of ordinary and even benign objects (in The Big Combo policeman Cornell Wilde is tortured by gangster Richard Conte with Brian Donlevy’s hearing aid). There is often a dream scene or a brief use of nightmare imagery, and frequently flashbacks that disrupt the narrative flow.

Along with the grotesque there are frequently suggestions of perversion — twisted sexuality just beneath the surface (in The Glass Key William Bendix’s Jeff virtually seduces Alan Ladd as he beats him, calling him “Baby”), Clifton Webb’s aesthete villain in The Dark Corner is either asexual or homosexual (homosexuality is inevitably presented as perversion in noir, but then so are most forms of heterosexuality).

The femme fatale in noir often seems to feed on and desire humiliation, and take a perverse pleasure in destruction like some strange incarnation of Kali or a Dionysian bacchanalia. It’s the old fear of female sexuality sharpened to a knife point.

The films are also marked by a sort of hyper acuity of the senses. Blacks are deeper, light areas brighter, edges more defined. In Phantom Lady when Elisha Cook Jr.s’ hophead drummer plays a solo it rises in crescendo into a near sexual climax. The interior of the big clock in The Big Clock looks like an alien spaceship. When Philip Marlowe falls into a black pool it swallows him and the viewer. The sharpness of edges in noir is one of the most important visual cues, one that becomes startlingly clear if seen on the big screen or on today’s HDTV’s with superior digital DVD or Blu Ray.

One last key element of many noir’s is narration. This can vary from the poetic hardboiled voice of Dick Powell’s Marlowe, Tom Brown’s doomed drifter, Chill Wills’ embodiment of Chicago in The City That Never Sleeps, or the dry baritone of Reed Hadley emotionlessly keeping us informed in the docu-noirs.

The narration is at its most effective in Sunset Boulevard when William Holden’s Joe narrates from his own murder scene. The narration allows us inside the head of characters in ways that dialogue can’t always. At the same time it reminds us we are all to some extent trapped in our own mind.

Not all of these elements are in every noir film, but enough of them predominate that they can be used to define the genre. There are always going to be films that are on the edge one way or another, and because of its nature I’m not sure noir can be defined precisely, but I’ll name seven key factors I think are vital.

1. Alienation.

2. Obsession

3. Visual Style

4. Destructive Sexuality

5. Grotesque characters

6. Narration

7. Stylized violence

Any four of those elements in one film and I think you have to grant it is noir, but three or less is problematic, and unless the psychological elements apply to the protagonist it probably isn’t noir.

And one last rule that will certainly be controversial — I don’t think you can really claim it is the Hollywood noir school if it is made before at least 1944, though it may be an immediate precursor of the genre (This Gun For Hire, Street of Chance, Journey Into Fear, Citizen Kane …).

I don’t think true noir exists without the catalyst of WWII and the returning veteran. Like the atomic genie, the war let loose a new twist in the American psyche as defined as Hemingway’s Lost Generation, and it is out of that and many tropes of popular literature and film that film noir arises, as clearly as the detective story comes into focus with Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes in ways it had not in the period from 1841 in Poe’s Rue Morgue until Holmes.

Many of the elements are there, but until the right moment they don’t become a distinct form.

Wed 4 Mar 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

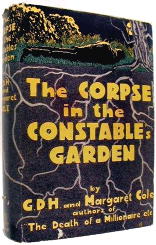

G. D. H. & M. COLE – The Corpse in the Constable’s Garden.

Collins Crime Club; UK, hardcover; 5th printing, 1933. US edition: Morrow, hardcover, 1931. Hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap, no date (shown). Previously published in the UK 1930 as Corpse in Canonicals, Collins, hardcover, 1930.

As was pointed out in both my review of the Coles’ Knife in the Dark and the one Bill Pronzini wrote for 1001 Midnights, which was posted here, most of the mysteries they wrote featured Superintendent Harry Wilson, of New Scotland Yard.

He appeared in, among others, both their first novel (The Blanchington Tangle, 1923) and their last (Toper’s End, 1942), along with a few short story collections published during World War II and later — up through 1948 or so.

And as usual for detective stories published during that particular time period, there’s not much said about Wilson’s private life, at least not in this book. The mystery’s the thing — but this is no sober and deliberate drawing room affair, either. It’s amusing, it’s droll, and in more than one scene, if it doesn’t cause out-and-out laughter, more than a few chuckles should result as well.

There are some hi-jinks with a valuable necklace in the early going, and then the local constable discovers that someone has left a body in his garden. (I don’t think I gave anything away by disclosing this, did I?) The inspector on the scene is shadowed by an overly eager (and equally suspicious) mystery writer who lives nearby, not to mention three undergraduate chums on a walking tour who also decide to give the locals a bit of a helping hand.

Maybe my sense of humor is different from yours. I’ll quote from page 96, and you can see for yourself:

“The last book you lent my wife,” said the Colonel, “was about a man who fell in love with a horse. Give me Edgar Wallace.”

“Don’t pretend to be a fool, Hubert,” said his wife. “You know you said you liked Proust.”

“I said I liked him in moderation,” said the Colonel. “The trouble was, there wasn’t any moderation.”

I simply can’t read that without cracking a smile, and I do every time I do. But if I found the previous book a little lax in the denouement, I certainly can’t say the same about this book. There is a closing scene with all of the characters in one room, and one by one Wilson eliminates them, just the way I would have, down to the final two — the only two I’d decided who could have done it — and then to the final culprit — the very same one I’d fingered for the job.

Is that a recommendation, saying the author’s solution dovetailed in exact precision as yours? Or can you say that if it’s that obvious, it’s can’t be any good? I’m leaning toward the former, since it wasn’t obvious, and if it had been the other fellow, and I wasn’t at all sure it wasn’t, I’d have been caught flat-footed. As I almost always am.

It’s sure a nice feeling when you get it right, though!

« Previous Page — Next Page »