April 2009

Monthly Archive

Mon 20 Apr 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Edward D. Hoch:

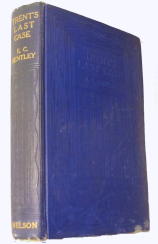

E. C. BENTLEY – Trent’s Last Case.

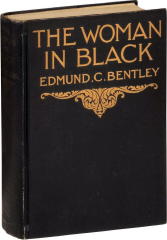

Thomas Nelson, UK, hardcover, 1913. First published in the US as The Woman in Black, Century, 1913. (Later US editions have the British title.) Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback. Also available as an online etext.

Silent film: Broadwest, 1920 (Gregory Scott as Philip Trent; Richard Garrick, director). Also (with partial sound): Fox, 1929 (Raymond Griffith as Philip Trent; Howard Hawks, director). Sound film: British Lion, 1952 (Michael Wilding as Philip Trent; Herbert Wilcox, director).

One of the true cornerstones in the development of the modern detective novel, Trent’s Last Case has received high praise for more than seventy years. G.K. Chesterton (to whom the book was dedicated) called it “the finest detective story of modem times,” while Ellery Queen praised it as “the first great modern detective novel.”

Later critics have tempered their praise somewhat, and Dilys Winn’s Murder Ink even lists the book in its Hall of Infamy among the ten worst mysteries of all time.

But there can be no doubt as to the book’s importance, especially in the character of detective Philip Trent. Before Bentley’s creation of Trent, fictional detectives had always been of the infallible, virtually superhuman type exemplified by C. Auguste Dupin and Sherlock Holmes.

English artist Philip Trent, investigating the murder of a wealthy American financier for a London newspaper, represents the birth of naturalism in the detective story. He falls in love with the victim’s widow (the woman in black of the original American title), who is the chief suspect in the case, and he is far from infallible as a detective.

Bentley wrote the book as something of an exposure of detective stories, a reaction against the artificial plots and sterile characters of his predecessors. But despite Trent’s fallibility, his detective work is skillful. The ending, with its surprise twists, is eminently satisfying.

Though slow-paced by modem standards, the book has a graceful prose and quiet humor that have stood up well with the passage of time. Mystery readers were not to see anything remotely like Trent’s Last Case until Agatha Christie’s initial appearance with The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1920.

Happily, Philip Trent’s last case wasn’t really his last, though E. C. Bentley waited twenty-three years before producing a sequel, Trent’s Own Case, written in collaboration with H. Warner Allen.

This time Trent himself is the chief suspect in a murder case, and if the book falls short of its predecessor, it is still a skillful and attractive novel.

Bentley followed it with thirteen short stories about Trent, written mainly for the Strand magazine, twelve of which were collected in Trent Intervenes (1938), a classic volume of anthology favorites. A final thriller, Elephant’s Work (1950), is more in the style of John Buchan and is less successful.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 19 Apr 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

Reviews1 Comment

A Review by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

E. C. BENTLEY – Elephant’s Work: An Enigma. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1950. Alfred A. Knopf, US, hardcover. 1950. Also published as The Chill. Dell 704, paperback, 1953.

E(dmund) C(lerihew) Bentley is one of the magical names in the mystery genre. His book Trent’s Last Case (1912) is usually cited as the birth of the Golden Age of the British detective novel, and certainly the book that carried the genre from the short form practiced by Doyle, Chesterton, and Morrison, to the novels championed by Christie, Sayers, Berkley and others.

In addition to the classic Trent’s Last Case Bentley also wrote a collection of short stories featuring journalist and amateur sleuth Philip Trent, Trent Intervenes (1938), and a second novel, Trent’s Own Case (1936) with H. Warner Allen, but then was silent in the field until 1950 when he penned Elephant’s Work: An Enigma.

And enigma is exactly what Elephant’s Work is. Bentley dedicated the work to John Buchan, and it is certainly in the form of a “shocker,” inspired when Bentley expressed his admiration for Buchan’s The Thirty Nine Steps and Buchan suggested Bentley pen his own. The result forty years later was this book. In retrospect he should have ignored the advice and stuck to detective stories.

The novel begins promisingly. The hero Severn boards a train where he encounters a formidable American and learns there is a dangerous fugitive abroad. As they wait, there is a ruckus coming from a nearby circus train. An elephant has escaped and gone on a rampage. When the elephant goes wild again on the train and causes a wreck, Severn is knocked unconscious.

When he awakens, he is suffering from amnesia and finds he is the guest of one General da Costa who informs him the name on his passport is Taylor, and while the General, the doctor, and everyone else are all perfectly kind, it soon dawns on Severn he is a virtual prisoner, and his fate is involved with someone known as Nick the Chill who works for a gangster called Farewell Billy.

In fact it is more than implied by the General and others that Severn is none other than Nick the Chill, a gunman in the employ of Farewell Billy.

So far so good. The writing is clean and clear and the suspense well calculated. The sense of mystery and Severn/Taylor’s confusion and growing paranoia well drawn. Is he the deadly Chill, or an innocent man being set up to take the fall in some elaborate scheme? Buchan himself could hardly have done it better, especially when Severn/Taylor eludes his protectors and tries to piece the mystery together pursued by mysterious sinister men and unable to go to the police who may believe he is a dangerous killer.

And then Elephant’s Work takes the most absurd twist you can imagine. I almost hesitate to reveal it, save unwary readers might think Elephant’s Work was a lost classic of the thriller genre only to run aground on the most unlikely reef in the history of the chase and pursuit novel.

Severn isn’t Taylor, and he isn’t Nick the Chill, he’s the Bishop of Glanister, on a little holiday before taking up his new duties — as the just appointed Archbishop of Canterbury — and the entire conspiracy has been the hastily contrived work of his friends attempting to protect him from any potential bad publicity while he was recovering his memory.

If at this point you feel the need to throw the book across the room, it is at least a small volume. Of course there is a bit more to it than that. The General himself was a fugitive of sorts who didn’t want Severn’s presence to reveal where he was until his situation was settled, but even that is hardly a satisfying explanation why everyone behaves in the most absurd manner possible and for the most absurd of reasons.

Ultimately Elephant’s Work is one of those annoying books where if anyone behaved halfway reasonably or made some effort to actually think, the entire facade would come crashing down like the house of cards the author has constructed. You should on general principle avoid any book which the author subtitles an “Enigma.” Chances are he means it.

This shouldn’t put anyone off reading Bentley’s classic detective novels. While it’s a bit dated, Trent’s Last Case is a genuine classic, and both Trent Intervenes and Trent’s Own Case are exceptional works in the genre.

Philip Trent is the model for many of the amateur sleuths to come later and especially an early influence on Dorothy L. Sayers and Lord Peter Wimsey. Bentley was a clever and charming man who gave his own name to the playful four line stanzas known as Clerihews he wrote in school and which were published with illustrations by G.K. Chesterton as Biography For Beginners. Bentley himself was a respected journalist and editorial writer for the Daily Telegraph.

But be forewarned, Elephant’s Work is one of the single most annoying thrillers ever written, light as a souffle only because it really is filled with hot air. And be careful where you throw it. You might upset an elephant and start the whole absurd business all over again.

The victim of Trent’s Last Case is the millionaire Sigsbe Manderson, that name being a motive for murder if nothing else, as some wag once pointed out. Trent’s Last Case was filmed twice, the second time as The Woman in Black with Michael Wilding as Trent and Orson Welles as Manderson.

Despite, or because of that, it’s a dull affair all around. Luckily we were spared the film version of Elephant’s Work — one of those small mercies we should be grateful for.

Sat 18 Apr 2009

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

P. G. WODEHOUSE – Wodehouse on Crime: A Dozen Tales of Fiendish Cunning.

Ticknor & Fields, 1981. International Polygonics Library, hardcover/trade paperback: 1991. Editor: D. R. Bensen, with a foreword by Isaac Asimov.

P(elham) G(renville) Wodehouse–“English literature’s performing flea” (Sean O’Casey) and “the funniest guy I ever read” (H & R Block)–was a master of comedy. Now, tastes vary as to what constitutes humor — the eruption of Krakatoa still provokes a laugh in some circles — but P.G. Wodehouse (“Plum”, or just “You, there”) is generally acknowledged as the best-of-the-best.

Wodehouse on Crime collects twelve stories from Wodehouse’s massive output of over six decades of writing. At first blush, you wouldn’t associate innocuous P.G.W. with criminal intent, would you (and why are you blushing)? As the late Isaac Asimov asks in his foreword: “Can there be crime in the never-never-land of P.G.W. idyllatry? Certainly! The tales are saturated with it, and even that does not weaken our love … when one stops to think of it, there is rarely a story in the entire Wodehouse opera which doesn’t feature crime.”

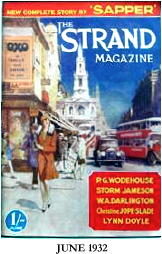

Editor D. R. Bensen adds that “… it would be impossible to present a full collection of those of P. G. Wodehouse’s stories which are concerned with crime. It would be a book of thousands of pages, with a spine about two and a half feet wide, which would make for awkward reading.” He also notes, tongue in cheek, the “baleful” influence that reading the Sherlock Holmes stories in the Strand had on the young and impressionable Plum.

However, be aware that if you’re seeking blood and gore and pick up Wodehouse on Crime, you’re in the wrong venue.

The first story in the collection, “Strychnine in the Soup,” is typically criminous Wodehouse. Plum’s Underwood portable here dispenses a lively story — a gentle spoof of Golden Age Mystery conventions — centering on Mr. Mulliner’s nephew Cyril, a diffident chap who encounters Miss Amelia Bassett at a play. After an awkward introduction — she grabs his leg — Cyril speaks first:

“You are evidently fond of mystery plays.”

“I love them.”

“So do I. And mystery novels?”

“Oh, yes!”

“Have you read Blood on the Bannisters?”

“Oh, YES! I thought it was much better than Severed Throats.”

“So did I,” said Cyril. “Much better. Brighter murders, subtler detectives, crisper clues … better in every way.”

Then, says the author, “The twin souls gazed into each other’s eyes. There is no surer foundation for a beautiful friendship than a mutual taste in literature.”

A little later, Amelia asks apropos of nothing: “Tell me … if you were a millionaire, would you rather be stabbed in the back with a paper-knife or found dead without a mark on you, staring with blank eyes at some appalling sight?” — a question we’ve all asked ourselves, I’m sure; but before Cyril can answer, in walks Amelia’s formidable mother …. but read “Strychnine in the Soup” for yourself, and the eleven other stories, too.

As with H. P. Lovecraft’s fiction, take P.G.W. in small doses for best results — you wouldn’t want to overdo it — in between, say, the disappearance of Mr. Davenheim’s moustache and the murder of Mrs. Twisby-Axleby’s trained albatross in that blood-drenched Golden Age mystery you’re currently reading. (Oh, and by the way, Mr. Mulliner’s solution to The Murglow Manor Mystery, mentioned in passing, is intricate … and completely loopy.)

To die an embittered misanthrope was the sad fate of too many of our great humorists — Mark Twain, S. J. Perelman, Soren Kierkegaard — but not so with P. G. Wodehouse: He reportedly kept a stiff upper lipper to the end, remaining at his post as the fort was being overrun by mutinous Sepoys and seditious Polyglots, a feather duster in one hand and his Underwood portable in the other.

That Plum: What a guy!

Contents:

“Strychnine in the Soup” (1932)

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1937)

“Ukridge Starts a Bank Account” (1967; reprinted in EQMM in 1982)

“The Purity of the Turf” (1923)

“The Smile That Wins” (1931)

“The Purification of Rodney Spelvin” (1927)

“Without the Option” (1927)

“The Romance of a Bulb-Squeezer” (1928)

“Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1923)

“The Fiery Wooing of Mordred” (1936)

“Ukridge’s Accident Syndicate” (1926)

“Indiscretions of Archie” (1921)

Addendum:

“I seem to keep finding, or I keep seeming to find, trace elements of Doyle in the Wodehouse formulations. I sense a distinct similarity, in patterns and rhythms, between the adventures of Jeeves as recorded by Bertie Wooster and the adventures of Sherlock Holmes as recorded by Dr. Watson ….”

So states Richard Usborne in his Plum Sauce: A P. G. Wodehouse Companion (2002). He goes on: “The high incidence of crime in the Wodehouse farces, especially the Bertie/Jeeves ones, may be an echo of the Sherlock Holmes stories, too — blackmail, theft, revolver shots in the night (Something Fresh), airgun shots by day (‘The Crime Wave at Blandings’), butlers in dressing-gowns, people climbing in at bedroom windows, people dropping out of bedroom windows, people hiding in bedroom cupboards, the searching of bedrooms for missing manuscripts, cow-creamers and pigs. I am not accusing Wodehouse of having concocted his stories deliberately on Doyle’s lines; I am saying that, of all the authors to whom Wodehouse’s debt shows itself, Doyle is second only to W. S. Gilbert. And Wodehouse would gladly have acknowledged both debts.”

That bears repeating: “… Doyle is second only to W. S. Gilbert” as an influence on the foremost humorist of the twentieth century.

Wodehouse admitted as much to a biographer: he “recalled the excitement of waiting for new issues of The Strand Magazine on Dulwich station” containing the latest Holmes adventures.

Another of Wodehouse’s characters was Psmith (pronounced “smith”). Usborne writes that one of the “strongest influences in the rhythms and locutions of the Psmith language was Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories … Wodehouse’s first major conversational parodist, Psmith, is constantly echoing Sherlock Holmes (indeed, the Holmes Valley of Fear influence probably to some extent suggested the plot of Psmith Journalist). Psmith has verbal ‘lifts’ from Sherlock Holmes, with direct quotations of words and copying of manner”; and Usborne produces several examples from the Psmiths and the Jeeves and Woosters.

Sat 18 Apr 2009

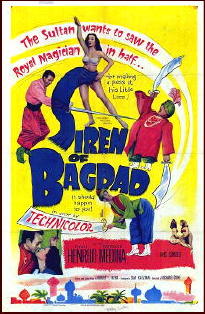

SIREN OF BAGDAD. Columbia Pictures, 1953. Paul Henreid, Patricia Medina, Hans Conried, Charlie Lung. Director: Robert Quine.

Turner Classic Movies had a salute to Hans Conreid the other day, which was kind of a surprise, as I don’t think anyone would consider him one of the great movie stars of the day, to put it frankly.

He began his career in radio — think Professor Kropotkin on My Friend Irma (1949), for example, a role he carried over to the film version, as did Marie Wilson in the title role, but most people remember the movie as the debut of a comedy team named Martin and Lewis — and he also did a lot of work on TV on up through the early 1980s.

But movies? Not really, that wasn’t his metier, but I taped the ones that TCM showed, and my reviews of them will show up here eventually. (Assuming that you don’t mind, I’ll exclude The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T from 1953, which I’ve seen before and I decided I’d pass on watching again.) Conreid was perfect for radio and TV sitcoms, though — he was also Uncle Tonoose on Danny Thomas’s Make Room for Daddy — loud, sneeringly brash and willing to do anything for a gag.

A role not unlike the one he plays in Siren of Bagdad, too. There’s a small amount of adventurous derring-do in the movie, but very little. The movie’s played for laughs all the way, and on the level of a mediocre radio show, much less TV, although the sets could have come from the same warehouse.

Samples:

Trying to distract a palace guard: “I beg your pardon. I realize they haven’t been invented yet, but have you got a match?”

Making his way with his boss, the magician Kazah the Great (Paul Henreid), to Bagdad: “The sands of the desert have barbecued my bunions.”

At a time when things are looking dark for the pair: “Where can I catch the next camel to Basra?”

Story line: When the dancing girls in his entourage are kidnapped by desert bandits and taken to Bagdad to be sold as slaves, Kazah the Great and Ben Ali (Conried) follow and fall in with some revolutionaries. The Great Kazah also falls in love with the leader’s daughter (Patricia Medina), and you can take it from there.

There is also a large magic trunk into which people are put, only to disappear, among other uses, including changing Ben Ali into a beautiful dancing girl (with Ben Ali’s voice, both unfortunately and amusingly), the better to infiltrate the Sultan’s harem. (Along this line of thinking, there is much to see in this movie.)

One would think that’s a long way down for Paul Henreid, from Now, Voyager and Casablanca to Siren of Bagdad, but to his credit, and this is the honest truth, he seems to be having a great time.

As for the director, Robert Quine, you may not be able to tell from this film, but he was on his way up — to films like My Sister Eileen (1955), The Solid Gold Cadillac (1955) and The World of Suzie Wong (1960), among a number of others.

Fri 17 Apr 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

REVIEWED BY TED FITZGERALD:

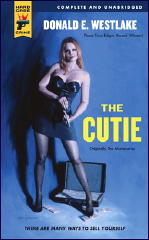

I realized, when I saw that Hard Case Crime was reissuing Donald Westlake’s The Mercenaries as The Cutie and that Ramble House was reissuing Ed Gorman’s The Night Remembers, that I’d reviewed both for Drood Review back in the early 1990s.

Here they are. I enjoyed them a lot, but I am curious as to what I’d have to say about them today, after 18 years of life…

From The Drood Review of Mystery, April 1991:

DONALD E. WESTLAKE – The Mercenaries. Carroll & Graf, reprint paperback, 1991. Random House, hardcover, 1960. Also published as: The Smashers, Dell, paperback, 1962; and as The Cutie, Hard Case Crime, 2009.

Thirty years lends a curious and bloodless innocence to Westlake’s debut novel. In The Mercenaries, the criminal organization is just that: a business enterprise run by suited, thin-lipped executives.

The protagonist is Clay, a dutiful middle manager who takes care of the details and shuts off his emotions when employees must be (literally) terminated. Those emotions get a workout, however, when he’s forced to play private eye to find the “cutie” whose murder of a connected man’s mistress may be the opening salvo in a power play aimed at Clay’s boss.

Written in steady, unobtrusive style, The Mercenaries speeds along, going almost too fast to allow us to figure out what Westlake’s trying to accomplish. Is this an early spin on blue-jawed gangster stereotypes, or a dry spoof of the then-popular Organization Man?

References and details and Clay’s early ’60s New York “sophistication” date marvelously. If all of the plot details don’t jell at the story’s conclusion, it’s because we see things through Clay’s eyes. And in the disorienting and ambiguous ending, Westlake foreshadows the genesis of one of his most famous characters, Parker.

From The Drood Review of Mystery, March 1991:

ED GORMAN – The Night Remembers. St. Martins, hardcover, 1991. No mass market paperback edition. Ramble House reprint: hardcover/trade paperback, 2008.

Sixtyish Jack Walsh, retired Cedar Rapids deputy turned private investigator, is presented with a classic predicament: the wife of a man he sent to prison wants him to prove her husband’s innocence. It takes one corpse (that of a would-be blackmailer) and one intimation of mortality (a cancer scare for Walsh’s lover) to put him on the job.

Gorman dedicates the book to Bill Pronzini “and somebody else who shall remain Nameless.” While there’s a superficial resemblance to Pronzini’s well-seasoned sleuth, the two characters’ real common ground is their maturity. Each brings his life experience to his cases, neither needs to be a tough guy and both are able to be empathetic and judgmental at the appropriate times.

Characterization is Gorman’s strong suit and he presents Walsh’s sensitivity without dropping into easy sentimentality. The sometimes awkward, sometimes silent relationship between Walsh and his mildly restless lover is uncomfortably true to life in the ’90s.

Fri 17 Apr 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

JAMES ROLLINS – Ice Hunt. William Morrow, hardcover, July 2003. Reprint paperback: Avon, June 2004.

Another of Rollins’ high-tech adventure thrillers, this time pitting Russian and American scientists and para-military teams against one another at the site of an abandoned polar cap laboratory where the results of horrific experiments, buried but not quite dead, have waited 70 years for the chance to feed again.

The fate of mankind rests on the outcome of the bloody struggle and I’m sure that you won’t think that I’m giving away anything if I tell you that mankind survives. After all, Rollins doesn’t want to wipe out everything that could keep his Tom Swiftian imagination from achieving more fictional successes.

Publisher’s Weekly is quoted as saying that “Rollins’s characters [are] fully drawn” in this “first-class roller-coaster.” Well, maybe fully but not deeply felt or imagined. As usual, the most compelling characterization is that of an animal (this time, a wolf), not surprising if you keep in mind that Rollins has a veterinary practice in Sacramento, California.

In case it wasn’t apparent from my lack-luster review, I ended my flirtation with Rollins’ work with this book.

Thu 16 Apr 2009

A WESTERN MOVIE REVIEW

by David L. Vineyard.

BUCHANAN RIDES ALONE. Columbia Pictures, 1958. Randolph Scott, Craig Stevens, Barry Kelley, Tol Avery, Peter Whitney. Based on the novel The Name’s Buchanan by Jonas Ward. Directed by Budd Boetticher.

Synopsis: Riding home through the border town of Agry, Tom Buchanan gets caught up in a feud between the lawless Agry brothers and a family of Mexicans.

Buchanan Rides Alone is a key film in the group of films Budd Boettticher did with Randolph Scott in the late 1950’s and is something of a comment on society as a whole. There’s nothing new about the newcomer riding into town and ending up cleaning the place up, but Buchanan goes about it in a singularly tough minded manner.

The characters played by Scott in these films are good men who have been driven by circumstance to become hard, and while they carefully guard a nugget of their humanity beneath that tough exterior they can be ruthlessly violent and even brutal when it’s warranted.

Because Buchanan Rides Alone is the first of a series of books and the character a sort of drifter, there is less backstory than usual in a Boetticher film. Buchanan would seem to be just another drifting cowboy looking for work — until someone pushes him the wrong way.

At that point it becomes clear just how far the Scott hero will go to restore what he considers his personal honor. In some ways his Buchanan has some relationship to John D. MacDonald’s later Travis McGee character, particularly in The Green Ripper. Once he has unleashed the man beneath the surface someone is going to pay in blood before he resumes his easy going facade.

That’s true of most western (and other) heroes but Scott and Boetticher together so refined and perfected the Scott persona in their movies together that they develop a sort of cinematic shorthand, a gesture, a look, a single word, that says more than pages of expository dialogue and background in other films.

In some ways Scott’s take on the iconic western loner is the dominant one in the western imagination, however important the Gary Cooper, John Wayne, or even Clint Eastwood model. Likely the truest moment in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles is when the townfolk remove their hats reverently at the mere mention of Randolph Scott’s name.

Barry Kelly is the corrupt town boss and Craig Stevens (just before Peter Gunn) a smooth gunfighter. There is nothing unusual in the plot, but the writing and direction are as superior as would be expected in a Boetticher film, and while the plot may be tried and true, the approach to character makes this one notable.

The surprising thing about the Boetticher films is that while they are set against the wide open spaces of the west, they are closely focused character studies of men under stress, particularly the Scott hero, who reveals depths of feeling and humanity with little more than a pained look or by holding himself a little apart from everyone else in the film.

I imagined the Buchanan of Jonas Ward’s series of books as someone along the line as Gary Cooper, but Scott at this time was at the height of his appeal, and his take on Buchanan combined a gentle charm that could turn to steel with a glint of his narrow eyes.

And it isn’t as if there weren’t close bonds between Scott and Cooper. Scott got his start in Hollywood as Coooper’s dialogue coach for The Virginian and replaced Cooper in the popular Zane Gray series of films. By the time he made the series of films with Boetticher his version of the western hero was almost as iconic as Cooper’s, though it has only been in recent years he’s gotten real credit as an actor in them.

At first glance Buchanan Rides Alone only seems to be a superior product of the heyday of the adult western, but there is more to the Scott character and to Boetticher’s direction than there may seem to be on the surface.

In the confines of a fairly common western story Boetticher is commenting on both contemporary American society, and also saying something about the idealized American character. Scott’s hero in these films is the man who does the right thing even when it’s messy and society might prefer that he look the other way. Once he is unleashed he will have a reckoning, whatever the price.

[EDITORIAL COMMENT.] A complete list of the “Buchanan” books by Jonas Ward can be found following my review of Buchanan’s Black Sheep, a much later entry in the series. David originally left this movie review as a comment following that earlier post. I’ve revised it slightly for its appearance here.

Thu 16 Apr 2009

On mystery writer’s Rafe McGregor’s blog today is a post called “The Speckled Band: The Worst Sherlock Holmes Story?”

I imagine that everyone over a certain age has read the story, and (I hope) many under that certain age. In order to discuss the story, though, certain elements of the plot have to be mentioned, so [WARNING: PLOT ALERT AHEAD].

I’d read this or a similar list of errors before, but here are at least some of them:

1. Snakes don’t have ears, so they cannot hear a low whistle.

2. Snakes can’t climb ropes.

3. Snakes can’t survive in an airtight safe.

4. There’s no such thing as an Indian swamp adder.

5. No snake poison could have killed a huge man like Grimesby Roylott instantly.

Rafe asks how detrimental these erroneous pieces of the plot are to the enjoyment of the story, to which some people have already replied. To me, the answer is “not very.” Holmes as a character is well beyond belief anyway, a wish fulfillment superhero in many ways — isn’t he? think about it — that quibbling over “small points” like the above is like asking how come Superman is so vulnerable to Kryptonite.

You might ask me tomorrow, though. I might have my science pants on by then, and I could easily have changed my mind.

I can tell you this, though. The story scared the heck out of me when I read it as a kid, which was probably when I was around eight years old. And was I relieved to know, whenever it was, that snakes can’t climb ropes? You bet.

Thu 16 Apr 2009

Posted by Steve under

AuthorsNo Comments

In the latest installment of his reviews of detective novels from the Golden Age of British Mystery Fiction, Al Hubin began his review of The Strelson Castle Mystery by saying “[author] Hal Pink’s obscurity in this country is total.”

Thanks to the wonders of the Internet, however, the obscurity that Al referred to, while true at the time he wrote the review, has lifted considerably. I added some information as an editorial update, and indefatigable UK researcher and archivist Steve Holland has taken the ball and run with it.

Please check out his Bear Alley blog for a long biographical post about Hal Pink, which incorporates all that’s known about him now, which is quite a bit, including a couple of photos, one of which I’ve borrowed and you see here.

Wed 15 Apr 2009

This will take a bit of an explanation, so bear with me.

Around the turn of last century, a relatively well-known mystery writer named Lawrence L. Lynch had quite a few books published. Some of them were reprinted later as by Emma Murdoch Van Deventer, and as John Herrington says, “At some time someone was able to match Lynch to Van Deventer [as to being the real name of the author], the connection being lost in the mists of time.”

The only problem is, no one has been able to find a real person having Van Deventer’s name, including John, and he’s been looking. He says, in part, “There are a few Emma Van Deventers on Ancestry.com, but Murdoch does not feature as part of any of these names.”

I’ll reprint all of Lynch’s entry in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, just for completeness, but the actual request is, if you know or can come up with any information about either Lawrence L. Lynch or Emma Murdoch Vandeventer, please leave a comment or drop me a line.

LYNCH, LAWRENCE L. Pseudonym of Emma Murdoch Van Deventer. [Note: There seem to be no books that appeared under the latter’s name only.] Except for two which apparently were never published in the US, these are the US titles only. All but one were reprinted in the UK by Ward Lock, including those as by Van Deventer, indicated by EMVD.

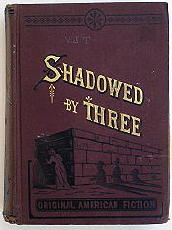

Shadowed by Three (n.) Donnelly 1879 [Neil Bathurst; Frank Ferrars]

The Diamond Coterie (n.) Connelley 1884 [Neil Bathurst]

Madeline Payne, the Detective’s Daughter (n.) Loyd 1884 [Madeline Payne] EMVD

Dangerous Ground; or, The Rival Detectives (n.) Loyd 1885 [Van Vernet]

Out of a Labyrinth (n.) Loyd 1885 [Neil Bathurst]

A Mountain Mystery; or, The Outlaws of the Rockies (n.) Loyd 1886 [Van Vernet; U.S. West]

The Lost Witness; or, The Mystery of Leah Paget (n.) Laird 1890 [New York City, NY]

Moina; or, Against the Mighty (n.) Laird 1891 [Madeline Payne]

A Slender Clue; or, The Mystery of Mardi Gras (n.) Laird 1891 EMVD

A Dead Man’s Step (n.) Rand McNally 1893 EMVD

Against Odds (n.) Rand McNally 1894 [Carl Masters; Chicago, IL] EMVD

No Proof (n.) Rand McNally 1895 [Chicago, IL] EMVD

The Last Stroke (n.) Laird 1896 [Frank Ferrars; Illinois]

The Unseen Hand (n.) Laird 1898 EMVD

High Stakes (n.) Laird 1899

Under Fate’s Wheel (n.) Laird 1901 EMVD

The Woman Who Dared (n.) Laird 1902

The Danger Line (n.) Ward 1903 [New York City, NY]

A Woman’s Tragedy; or, The Detective’s Task (n.) Ward 1904 [Carl Masters; Wyoming]

The Doverfields’ Diamonds (n.) Laird 1906 EMVD

Man and Master (n.) Laird 1908 [Carl Masters]

A Sealed Verdict (n.) Long 1910 [Chicago, IL] No UK edition.

A Blind Lead (n.) Laird 1912 EMVD

Notes: Titles with links can be found as etexts online. [See the comments for a list of five more.]

« Previous Page — Next Page »