July 2009

Monthly Archive

Thu 23 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

ROBERTSON DAVIES – High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories. Viking, US, hardcover, 1983; Penguin, softcover, many printings. First edition: Penguin Canada, 1982.

Robertson Davies was a writer of considerable talent, and every Christmas he used to tell a ghost story to the students at Massey College. These tales are gathered together in High Spirits, and they make for fun, if not very spooky, reading.

The tales in fact, are all mildly humorous and set very firmly in the context of Academia (hardly surprising, considering the audience). Thus we get stories of the spirit of a Grad Student, doomed to endlessly defend his thesis, the ghost of a forgotten University President, the souls of Canadian writers yearning to be re-born as American writers, and that sort of thing.

Former Academicians both past and present could probably relate to these, and I found them entertaining enough, but hardly the sort of thing to evoke shudders in the Season of the Witch.

Thu 23 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

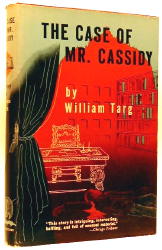

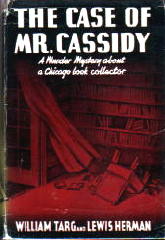

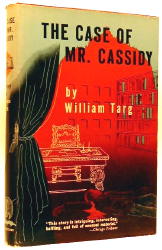

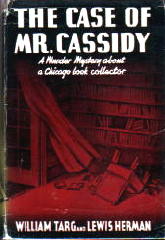

WILLIAM TARG – The Case of Mr. Cassidy.

World Publishing Company, hardcover reprint, 1944. Originally published by Phoenix Press, hc, 1939, as by William Targ & Lewis Herman.

This entertaining mystery, set in Chicago (the hometown of William Targ), introduces the erudite, paunchy amateur sleuth, Hugh Morris, who negotiates the pre-WWII Chicago literary scene as he keeps one step ahead of the police in their attempt to discover who murdered wealthy bibliophile James Cassidy and, subsequently, his private secretary.

The police are convinced that the murderer was the mysterious Fiend, who has previously only murdered attractive young women in open areas.

When the police corner and capture the Fiend, opportunely discovered with the body of his latest female victim, he readily confesses to the murder of Cassidy and his secretary, but, convinced that the Fiend is not the murderer of the two men, Morris continues his investigation.

It leads him to Chicago nightclubs, bookstores, and restaurants, familiar landmarks that bring him with such personalities of the period as collector and author Vincent Starrett and bookstore owner Ben Abramson.

Targ’s characters in his novel are skillfully if sketchily portrayed, with the exception of Morris, who comes off as a novelistic alter ego for Targ, sharing the same passionate interest in food, books, and the Chicago scene that characterize Targ as he describes himself in Indecent Pleasures (Macmillan, 1975), his compulsively readable biography.

In addition to the obvious pleasure a book collector will take in the bibliophile aspects that include the important clue of a first edition of Poe’s Tamerlane, the fan of period prose will find some choice linguistic prose rhapsodies, like the following:

Morris grinned when he realized the humor of the situation. Here he was, seated in a White Castle hamburger joint waiting for a ‘triple-size’ melange of chopped beef, bread-crumbs and God-knows-what to fry. Yet only an hour ago he had barely avoided satisfying his appetite with a Madame Galli dinner, a soul-appeasing morsel of shrimp, or a generous assortment of smorgasbord.

Now, with the memory of them still lingering in his mind’s stomach, he had gone into the hamburger shack for his evening meal. The unpredictable irrationality of the human animal, he thought, was what made it a fit subject for Shakespeare’s plays, T. S. Eliot’s poems and Mozart’s music. Man is a hamburger sandwich, he mused, an olla podrida of everything and of nothing, of God-knows-what.

The counter-man is God. He fashions and molds the blob of meat in his hands. The flavor is enhanced by the onions of the earth from which man sprang and the mustard of experience with which he is being constantly smeared. The pickle is the spice of life. The result, like a hamburger sandwich, is always a question mark–the perfect peristalsis of success or the bellyache of failure.

Morris picked his teeth as he thought of the gastronomic theme he had developed, and decided it was definitely beneath his standard of philosophic improvisation. He belched and left the place.

Rex Stout, eat your heart out!

N.b. The Tower reprint (from which I was working) dropped the Herman by-line, but a query to Al Hubin confirmed that the Phoenix first edition did list both Targ and Herman as co-authors. (See also the cover above.)

Thu 23 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini:

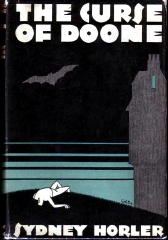

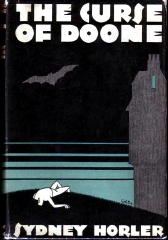

SYDNEY HORLER – The Curse of Doone. Hodder & Stoughton, UK. hardcover, 1928. Mystery League, US, hardcover, 1930. US paperback reprint: Paperback Library 53-931, 1966.

A journalist and writer of football stories (the British variety) until his early thirties, Sydney Horler began publishing “shockers” in 1925 and went on to produce upwards of a hundred over the next thirty years.

He created a menage of series characters, most of them Secret Service agents of one kind or another, including Bunny Chipstead; “The Ace”; Nighthawk; Sir Brian Fordinghame; and that animal among men, Tiger Standish.

The Standish books — Tiger Standish Steps on It (1940) is a representative title in more ways than one — were especially popular with Horler’ s readership. His greatest literary attribute was his imagination, which may be described as weedily fertile.

His favorite antagonists were fanatic Germans and Fu Manchu-type megalomaniacs, many of whom were given sobriquets such as “the Disguiser,” “the Colossus,” “the Mutilator,” “the Master of Venom,” and “the Voice of Ice”; but he also contrived a number of other evildoers to match wits with his heroes — an impressive list of them that includes mad scientists, American gangsters, vampires, giant apes, ape-men from Borneo, venal dwarfs, slavering “Things,” a man born with the head of a wolf (no kidding; see Horror’s Head, 1934), and — perhaps his crowning achievement — a bloodsucking, man-eating bush (“The Red-Haired Death,” a novelette in The Destroyer, and The Red-Haired Death, 1938).

The Curse of Doone is typical Horler, which is to say it is inspired nonsense. In London, Secret Service Agent Ian Heath meets a virgin in distress named Cicely Garrett and promptly falls in love with her. A friend of Heath’s, Jerry (who worries about “the primrose path to perdition”), urges him to toddle off to his cottage in Dartmoor for a much needed rest.

Which Heath does, though not before barely surviving a mysterious poison-gas attack. And lo! — once there, he runs into Cicely, who is living at secluded and sinister Doone Hall.

He also runs into a couple of incredible coincidences (another Horler stock-in-trade); monstrous vampire bats and the “Vampire of Doone Hall”; two bloody murders; hidden caves, secret panels and caches; a Prussian villain who became a homicidal maniac because he couldn’t cope with his sudden baldness; and a newly invented “war machine” that can force enemy aircraft out of the air by means of wireless waves and stop a car from five miles away.

All of this is told in Hoder’s bombastic, idiosyncratic, and sometimes priggish style. (Horler had very definite opinions on just about everything, and was not above expressing them in his fiction, as well as in a number of nonfiction works. He once said of women: “Of how many women can it truly be said that they are worthy of their underclothes?” And of detective fiction: “I know I haven’t the brains to write a proper detective novel, but there is no class of literature for which I feel a deeper personal loathing.” Racism was another of his shortcomings; he didn’t like anybody except the English.)

This and Horler’s other novels are high camp by today’s standards; The Curse of Doone is just one of several that can be considered, for their hilarious prose, pomposity, and absurd plots, as classics of their type.

Unfortunately, most of Horler’s “shockers” were not reprinted in this country. Of those that were, the ones that rank with The Curse of Doone are The Order of the Octopus (1926), Peril (1930), Tiger Standish (1932), Lord of Terror (1937), and Dark Danger (1945).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 22 Jul 2009

SCORPIO ROOMS: VICTOR CANNING ON TV

by Tise Vahimagi

From flash to futile: the Spy/Espionage genre in 1960s cinema and television. Seldom could a vogue have sprung so quickly from so little, and progressed so hurriedly from fresh beginnings to extravagant decadence and self-parody.

Fortunately, for television at least, Victor Canning was one of those astute writers who was all too aware of the genre’s doomed direction and managed to maintain a masterly hand in its various manifestations with dexterity and with dignity.

Recent re-examination of his TV career has revealed an astonishingly prolific contributor to the small screen. For devotees of Canning’s work, the 1960s must have been pure bliss. Various single plays, a sequence of multi-part serials, forays into episodic drama, each with its own particular flavour of veiled menace and sinister associations.

Earlier TV credits had largely been adaptations of his short stories, more often in the tenor of the safe than the surprising: “Never Trust a Lady” (CBS, 1953), with Marcel Dalio as a silky gentleman burglar; “A Thief There Was” (CBS, 1956), the misadventure of a jewel thief; “Disappearing Trick” (CBS, 1958), the comeuppance of a blackmailer; “Man on a Bicycle” (CBS, 1959), with Fred Astaire as a likeable con-man; and “Girl in the Gold Bathtub” (CBS, 1960), a gentle yarn about an American ad agency man sent to Italy to retrieve the title combination.

His 1960s quintet of serialised dramas, however, belong not so much to the espionage or the thriller form as to a new kind of anxiety fantasy, with their brooding heroes nursing neurotic doubts about their predicament.

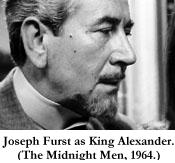

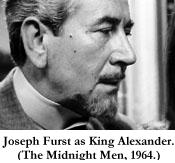

The first, The Midnight Men (BBC, 1964), was set in 1913 and featured a foolhardy Andrew Keir as a crack-shot recruit in an assassination plot to kill a king in a Balkan state.

A rescue thriller (with shades of The 39 Steps) formed the basis of Curtain of Fear (BBC, 1964) in which a cabaret performer, Miss Memory, is kidnapped while under hypnosis and carrying state secrets in her extraordinary memory (which sounds uncannily similar to his later novel Memory Boy, 1981); George Baker was the perplexed fiancé in pursuit, dodging various British and Russian agents.

Contract to Kill (BBC, 1965) returned to an Ambleresque milieu with a Frenchwoman seeking revenge on a Nazi for the murder of her son during the war, a German secret society pledged to aid ex-Nazis on the run, and with freelance agent Jeremy Kemp embroiled in the murky activities.

Taking the form of a more conventional thriller, Breaking Point (BBC, 1966) tells of a metallurgist who has discovered a form of steel which is immune to metal fatigue, and the security agent assigned to protect him and his discovery from hostile international interests. The suspense of imminent discovery sustained This Way for Murder (BBC, 1967), involving a sinister corporate crime structure and its infiltration by reformed ex-crook Terence Longdon on behalf of British police.

It was somewhat disheartening to learn that (save an episode or two, and with only This Way for Murder remaining complete) all the above BBC serials have been junked.

More straightforward crime elements — the TV plays about diamond thieves in Miracle on Mano (ITV, 1962) and Double Stakes (ITV, 1963), blackmail in Come Into My Parlour (ITV, 1965), working admirably in terms of involvement and suspense — were woven into stories for BBC’s Paul Temple (1969-71) and the suspense anthology The Man Outside (1972), adding an understated, realistic quality.

Surprisingly, there was even a two-part Mannix story in 1975 (scripted by Alfred Hayes) based on his 1951 novel Venetian Bird.

The chill awareness of a lethal cloak-and-dagger world, however, couldn’t help but surface in the conspiracy-obsessed British Intelligence agent series The Rat Catchers (ITV, 1966-67) for which Canning composed two three-part stories, cheerfully spreading characters and plot across various European locales.

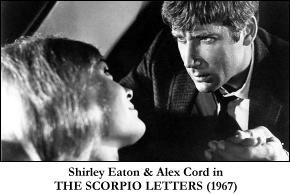

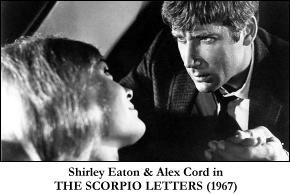

The MGM TV film The Scorpio Letters (ABC, 1967) arrived somewhere between talkative mystery and uneventful spy thriller. Alex Cord’s laconic, mildly sardonic agent hero and the film’s underlying theme about the corrupting effect of temporarily-acceptable violence in wartime failed to stimulate the main plot: the discovery of the elusive blackmailer Scorpio.

The always-interesting Man in a Suitcase (ITV, 1967-68), often entangled in its own conspiracies, produced the absurdly compelling “Blind Spot” in which Canning had Richard Bradford’s usually impassive McGill warm to a blind girl he is protecting as a ‘witness’ to a murder.

The counter-spy series Codename (BBC, 1969-70), about a British spy cell which uses a university as its cover, also called on Canning for a story, allowing him further exploration of the cool and brutal sophistication about Intelligence procedure, and its extreme ingenuity as a mechanism.

For the completists, there is also a German made-for-TV film, Das ganz grosse Ding, produced in 1965, but I have been unable to determine the original Canning story source.

Some modern references suggest Canning appeared as an actor in a 1967 episode (“The Mercenary”) of BBC police series Dixon of Dock Green. On consulting BBC TV Broadcast Programme information (a record of actual BBC transmission details) for this particular episode, I found that although there is no Victor Canning given in the cast list there is an actor called Victor Winding playing ‘Ben Chambers’. Perhaps this soundalike name was the source of the confusion…?

Victor Canning Television:

1. “Never Trust a Lady” / Your Jeweler’s Showcase (CBS, 9 June 1953). Dir: Ralph Murphy. Scr: Howard J. Green, adapted by Frank L. Moss; from original story by Canning. Cast: Marcel Dalio, Ray Teal, June Vincent.

2. “A Thief There Was” / Appointment With Adventure (CBS, 18 Mar 1956). Dir: Paul Stanley. Scr: Victor Canning, from story by Abby Mann. Cast: Christopher Plummer, Jason Robards, Constance Ford.

3. “Disappearing Trick” / Alfred Hitchcock Presents (CBS, 6 Apr 1958). Dir: Arthur Hiller. Scr: Kathleen Hite, based on s.s. by Canning [UK ed. Argosy, Sept 1957]. Cast: Robert Horton, Betsy von Furstenberg, Perry Lopez.

4. “Man on a Bicycle” / General Electric Theatre (CBS, 11 Jan 1959). Dir: Herschel Daugherty. Scr: Jameson Brewer, from short story “Young Man on a Bicycle [Cosmopolitan, Oct 1955]. Cast: Fred Astaire, Roxane Berard, Stanley Adams.

5. “Girl in the Gold Bathtub” / The U.S. Steel Hour (CBS, 4 May 1960). Dir: Allen Reisner. Scr: Robert Van Scoyk, from [original?] story by Canning. Cast: Marisa Pavan, Jessie Royce Landis Edward Andrews, Johnny Carson.

6. “Miracle on Mano” / Play of the Week (ITV, 14 Aug 1962). Dir: John Hale. Scr: VC. Cast: Patrick Magee, Derek Francis, Alan Tilvern.

7. “Double Stakes” / Play of the Week (ITV, 7 May 1963). Dir: John Hale. Scr: VC. Cast: Nigel Davenport, Jane Hylton, Richard Shaw.

8. The Midnight Men (serial; BBC, 21 June-26 July 1964; 6 x half-hour). Prod/Dir: Rudolph Cartier. Scr: VC. Cast: Laurence Payne, Andrew Keir, Derek Francis, Eva Bartok.

9. Curtain of Fear (serial; BBC, 28 Oct-2 Dec 1964; 6 x half-hour). Prod/Dir: Gerald Blake. Scr: VC. Cast: Colette Wilde, George Baker, John Breslin, William Franklyn.

10. Contract to Kill (serial; BBC, 3 May-7 June 1965; 6 x 25 mins). Prod: Alan Bromly. Dir: Peter Hammond. Scr: VC. Cast: Jeremy Kemp, Pauline Bott, Ronald Radd.

11. “Come Into My Parlour” / Suspense Hour (ITV, 11 July 1965). Dir: John Cooper. Scr: VC. Cast: Keith Barron, Renny Lister, Ray Barrett.

12. “Operation Lost Souls” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 13 Apr 1966). Dir: Bill Hitchcock. Scr: VC. Regular Cast: Glyn Owen, Gerald Flood, Philip Stone; Tom Watson, Bernard Kay, Sally Home.

13. “Operation Irish Triangle” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 20 Apr 1966). Dir: Bill Hitchcock. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Eugene Deckers, Rachel Gurney, Patricia Haines.

14. “Operation Big Fish” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 27 Apr 1966). Dir: Bill Hitchcock. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Eugene Deckers, Rachel Gurney, Alan Gifford.

15. Breaking Point (serial; BBC, 22 Oct-19 Nov 1966; 5 x 25 mins). Prod: Alan Bromly. Dir: Douglas Camfield. Scr: VC. Cast: William Russell, Rosemary Nicols, Richard Hurndall.

16. “Mission to Madeira” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 22 Dec 1966). Dir: Don Gale. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; John Abineri, Hannah Gordon, Richard Warner.

17. “Death in Madeira” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 5 Jan 1967). Dir: Don Gale. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Frederick Treves, Hannah Gordon, Susan Engel.

18. “Midnight Over Madeira” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 12 Jan 1967). Dir: Don Gale. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Frederick Treves, Susan Engel, John Abineri.

19. The Scorpio Letters (TV film; ABC, 19 Feb 1967). Dir: Richard Thorpe. Scr: Adrian Spies, from 1964 novel. Cast: Alex Cord, Shirley Eaton, Laurence Naismith, Oscar Beregi. [Cinema release in UK in May 1968]

20. This Way for Murder (serial; BBC, 3 June-8 July 1967; 6 x 25 mins). Prod: Alan Bromly. Dir: Eric Hills. Scr: VC. Cast: Hugh Cross, Terence Longdon, Isobel Black.

21. “Blind Spot” / Man in a Suitcase (ITV London, 10 Feb 1968). Dir: Jeremy Summers. Scr: VC. Cast: Richard Bradford, Marius Goring, Felicity Kendall.

22. “The Alpha Man” / Codename (BBC, 9 June 1970). Dir: Ronald Wilson. Scr: VC. Cast: Clifford Evans, Anthony Valentine, Alexandra Bastedo.

23. “With Friends Like You, Who Needs Enemies?” / Paul Temple (BBC, 30 June 1971). Dir: Michael Ferguson. Scr: VC. Cast: Francis Matthews (Paul Temple), Ros Drinkwater (Steve), George Sewell.

24. “Cuculus Canorus” / The Man Outside (BBC, 16 June 1972). Dir: Raymond Menmuir. Scr: VC. Cast: Rupert Davies (intro); Anthony Hopkins, Gerald Flood, Michael Gambon.

25. “Never Trust a Lady” / Of Men and Women (TV special; ABC, 6 May 1973). Dir: Lee Phillips. Scr: Harry Musheim, from Canning’s story. Cast: Jack Cassidy, Barbara Feldon, Mary Jackson.

26. “Bird of Prey” (two-part episode) / Mannix (CBS, 2 & 9 Mar 1975). Dir: Michael O’Herlihy. Scr: Alfred Hayes, based on the 1951 novel Venetian Bird. Cast: Mike Connors, Richard Evans, Robert Loggia.

27. The Runaways (TV film; CBS, 1 Apr 1975). Dir: Harry Harris. Scr: John McGreevey, from 1972 novel. Cast: Dorothy McGuire, Van Williams, John Randolph, Neva Patterson.

Wed 22 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Francis M. Nevins:

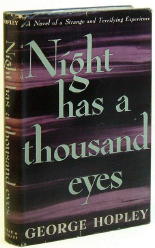

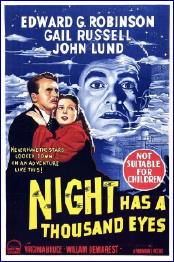

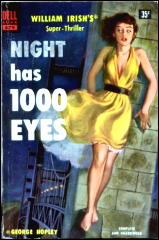

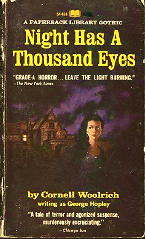

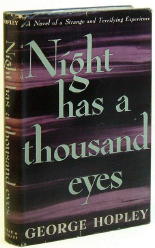

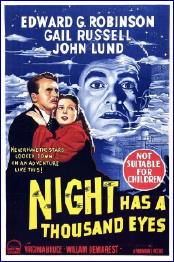

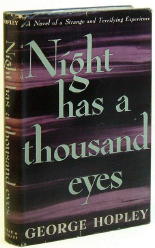

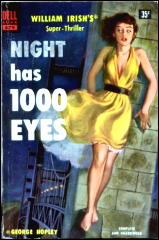

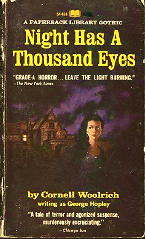

GEORGE HOPLEY – Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1945. Reprinted as by William Irish: Dell #679, 1953. Reprinted as by Cornell Woolrich: Paperback Library 54-438, 1967. Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes was the first of two novels published under a pseudonym made up of Cornell Woolrich’s middle names, and of all his books it’s the one most completely dominated by death and fate. A simpleminded recluse with apparently uncanny powers predicts that millionaire Harlan Reid will die in three weeks, precisely at midnight, at the jaws of a lion.

The tension rises to an unbearable pitch as the apparently doomed man, his daughter, and a sympathetic young homicide detective struggle to avert a destiny that they at first suspect and soon come to hope was conceived by a merely human power.

Woolrich makes us live the emotional torment and suspense of the situation until we are literally shivering in our seats.

The roots of Woolrich’ s longest and perhaps finest novel lie deep in his past. From the moment at the age of eleven when he knew that someday he would have to die, he “had that trapped feeling,” he wrote in his unpublished autobiography, “like some sort of a poor insect that you’ve put inside a down-turned glass, and it tries to climb up the sides, and it can’t, and it can’t, and it can’t.”

Of all the recurring nightmare situations in his noir repertory, the most terrifying is that of the person doomed to die at a precise moment, and knowing what that moment is, and flailing out desperately against his or her fate.

This is what connects the protagonists of Woolrich’ s strongest work, including Paul Stapp in “Three O’Clock,” Robert Lamont in “Guillotine,” Scott Henderson in Phantom Lady, and of course Reid in Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Only a writer tom apart by human mortality could have created these stories.

Published under a new by-line and by a firm never before associated with Woolrich, Night Has a Thousand Eyes seems to have been intended as a breakthrough book, to introduce the author to a wider audience, but it was too grim and unsettling for huge commercial success.

The 1948 movie version, starring Edward G. Robinson as a carnival mind reader with the power to foresee disasters, had almost nothing in common with the story line of Woolrich’ s novel, let alone its power and terror.

This book is what noir literature is all about, a nerve-shredding suspense classic of the highest quality and a work that once read can never be forgotten.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 22 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

GEORGE HOPLEY – Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1945. Reprinted as by William Irish: Dell #679, 1953. Reprinted as by Cornell Woolrich: Paperback Library 54-438, 1967. Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

Cornell Woolrich, that twisted and tortured man who haunted the novel of suspense like some Twentieth Century Poe, coined the term “line of suspense” to describe the mechanism that drives a good suspense novel.

In the simplest terms it is the element that drives the tale from one incident to the next — perhaps the killer’s motive as in The Bride Wore Black, the heroes amnesia as in Black Curtain, or here, in Woolrich’s masterpiece, the possibility of psychic powers and the inevitability of fate.

Woolrich’s novels are haunted by fate, sheer blind cruel and pointless fate. An unmarried pregnant woman on a train survives an accident and happens to be mistaken for another pregnant woman in the same car whose husband’s wealthy family has never seen her; a night’s drunk finds you facing the hot seat with no memory of what happened; a leopard escaped from an night club act cloaks the twisted mind of a killer; a sailor and a taxi dancer have only until dawn to clear him of a crime…

Fate is always having its little joke in Woolrich’s novels and stories, and in Night Has 1000 Eyes that little joke is at its most effective, and terrible.

Night opens appropriately at night. The hero is a young detective who spots an attractive young woman attempting suicide. He stops her, only to find she is desperate and frightened out of her wits.

Her wealthy father has been threatened, but this is no ordinary threat. A man claiming psychic powers has told her that her father will die at an appointed time and cannot be saved. And this psychic is never wrong.

Never.

Naturally the police take a dim view of this sort of thing, even though the psychic seemingly has asked for no money and committed no crime. But they encounter clever bunco artists all the time and they know that if they look deep enough they’ll find the game behind this one. Besides you can’t go around threatening a cities most wealthy men with blind retribution — it makes the taxpayers nervous.

Meanwhile the clock ticks and the time nears when the appointed hour will come.

And for every step forward there is one back, and still the uncanny predictions of this strange man come true.

When they finally uncover a tawdry romantic triangle involving the psychic, the victim, and the girl’s late mother they are certain they have the key — revenge and extortion. Still, they take no chances. They ring the victim with police and arrest the psychic who insists he means no harm to his old friend, and that he too will die shortly after the first man at his own appointed hour.

Now Woolrich ratchets the horror up to incredible levels. The tension is palpable and the suspense grows as each twist, each revelation comes. The psychic has predicted the man will die between the paws of a lion, and as the hour nears a lion escapes from the zoo, loose in the very area where the victim lives.

Mere coincidence, and yet …

And yet.

Ernest K. Gann coined the term “fate is the hunter” to explain why he left commercial aviation — because at some point in a pilot’s career the laws of simple math catch up with him and it becomes more likely he will crash than that he won’t. Woolrich understood the idea. Fate is a remorseless hunter, but Woolrich knows too you can’t run or hide.

Night Has a Thosand Eyes is a suspense novel and not a horror novel, but rightly has been claimed by both genres because the effect of the accumulation of events and coincidence begins to resemble something supernatural, though at each and every turn Woolrich is careful to eschew the simple explanation.

Again and again he takes the reader right up to the point of madness, and then pulls away, reveals another twist, shows us another possible path, all the while maintaining a palpable line of suspense that is almost unbearable.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a fairly long novel, but I have a hard time believing anyone once starting it put it down before it ended. Or slept much afterward.

And that may be where this book most resembles a horror novel and not a suspense novel, because most good suspense novels let you go when they come to the end. There is a build up to incredible tension and then a release.

Not in Night Has a Thousand Eyes.

If anything this book is more disturbing when it is over.

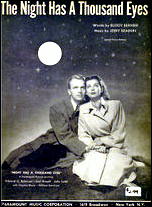

Night Has a Thousand Eyes was well filmed by John Farrow with a fine screenplay by Barré Lyndon and Jonathan Latimer, with Gail Russell perfectly cast as the fey girl, John Lund the hero, Edward G, Robinson the psychic, William Demarest a doubting cop, and Jerome Cowan the doomed victim.

It’s a fine piece of film noir, but it is only a pale shadow of the novel. I don’t know that you could translate on film the tension that Woolrich builds in print. I’m not sure you’d want to, because as I say, Night Has a Thousand Eyes doesn’t let you off the hook. Not even when you have turned the last page and laid the book aside.

The book also inspired a popular song that warned us “The night has a thousand eyes/ and a thousand eyes can’t help but see…” recorded by Bobbie Vee, and the song from the film by John Brahin was and still is a popular jazz riff. (Follow the link to a YouTube video of the Bobby Vee version.)

That title has the ring of some ancient bit of wisdom or poetry. It has the feel of found wisdom, of something we all knew, but never put into words before this.

The night has one thousand eyes and they are watching us. We cannot run from them, we cannot escape them. Fate will not be denied, nor can any man escape his appointed time. We all will make our own appointment in Samara on time.

And perhaps it is that inevitability that gives this novel its power. We aren’t let off with easy answers, and though the solution leaves itself fully open for rational explanation there is a cold dark corner of the soul that knows that isn’t what Woolrich was telling us.

Woolrich wrote only one other as George Hopley, the majority of his work appearing as by Woolrich or William Irish. Many of his novels deserve to be read and reread, they are masterpieces of suspense, and despite his tendency to overheated prose even the least of them are worth rereading. But Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a special case.

Even among his output of taut and often disturbing novels, this one is a masterpiece. This is the one unforgettable novel in his repertoire.

Read it and you will never forget it.

But don’t read it before bedtime.

Not if you ever want a good night’s sleep again.

Tue 21 Jul 2009

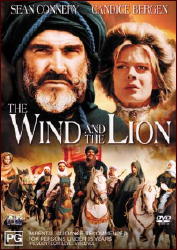

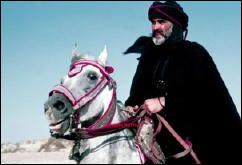

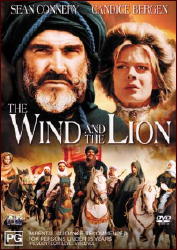

THE WIND AND THE LION. MGM, 1975. Sean Connery, Candice Bergen, Brian Keith, John Huston. Screenwriter & director: John Milius.

I’ve taken my time in getting my notes and opinions written up on this film, a semi-historical movie I watched about a week ago. It’s one that takes place during the tenure of Teddy Roosevelt in office of the President of the United States; or in other words, circa 1905.

There was at that time an actual American citizen kidnapped by a tribe of Berbers in Morocco, but the victim then was a man, and in the movie it is a woman (Candice Bergen) with two young children.

Doing the kidnapping is Mulay Hamid El Raisuli, Lord of the Riff, Sultan to the Berbers, Last of the Barbary Pirates (Sean Connery), and if Sean Connery can play El Raisuli as well as he does in The Wind and the Lion, why then, he can play almost anybody. (But we all knew that anyway, didn’t we?)

This causes a diplomatic crisis of huge international proportions. Almost as good as Sean Connery is in his role is Brian Keith in his, that of Teddy Roosevelt, and you should take it for granted that no one has or ever will play Teddy Roosevelt (in full imperial mode) as well as Brian Keith.

Global politics being what they were, both the French and Germans are involved in the attempt to negotiate the return of the kidnapped woman, Eden Pedecaris, but with Roosevelt’s “Big Stick” policy as backup plan, if you the viewer are ever in doubt as to whether or not the US Marines will be called in, you need not be concerned.

They are, and in full force. Part of the thrill of watching this movie is for the sheer adventure of it all. With the US in full cognizance of its new role in the world, the Marines are simply itching to take over, and eventually they do.

While John Milius is a strong right-of-center conservative — and if I’m in error about that, please let me know — his portrayal of the Moroccan Arabs and the plight of the nomadic tribes in the face of oncoming history feels (to me) both accurate and sympathetic.

The thrust of the tale, of course, is the conflicting bond between El Raisuli and his prisoner, the outspoken and openly defiant Mrs. Pedecaris, who in turn grows to respect her captor and his increasingly desperate situation more than she ever realized she ever would or could.

And yet. All is well and good in my description so far, but there was much to this film that equally displeased me — well, no, disappointed is a far better word. Each scene was well-set and well-filmed, but I found there was no cohesive structure to the film, or at least not enough, and events that were meant to be personal were shot as if at arm’s length far too often, as it were — if not literally, then figuratively speaking.

It is not clear (or not to me) how and why the Germans got so intimately involved in Raisuli’s capture at the end, but that Mrs Pedecaris had something to say about that was both rousing and satisfying.

If this sounds like a mixed review, I’m as surprised as you are. When I started writing up my thoughts about the movie, I was prepared to go almost totally negative, and I ended up far more positive than I expected.

(I no longer plan out ahead of time what I am going to say in one of these reviews. After a certain amount of time has passed by, and this varies, I simply sit down and start typing.)

There are a lot of artfully created scenes in this movie, and I am sure that is why it received a considerable number of nominations for various awards or another. If you like a rousing adventure movie as much as the next guy, I think you’ll enjoy it as much as he does.

Tue 21 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

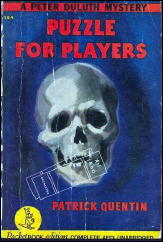

PATRICK QUENTIN – Puzzle for Players. Pocket #164, paperback reprint; 1st printing, June 1942. Hardcover edition: Simon & Schuster, October 1938. Victor Gollancz, UK, hc, 1939. US hardcover reprint: Books Inc., 1944. Paperback reprints include: Cherry Tree #301, UK,1940; Handi-Book #53, 1946 [abridged]; Avon, 1979; International Polygonics Ltd., 1989.

This is the second of author Patrick Quentin’s Peter Duluth mysteries, the first being Puzzle for Fools, reviewed here (by Marv Lachman) and in the post just preceding this one. There were nine books in the series in all, written between the years 1936 and 1954.

The titles of the first six of which began with the word “Puzzle,” indicating the author’s interest in clues, alibis and the other standard equipment of the mystery novel as a work of Golden Age detection, but as time went on, the later books began to depend more and more on matters psychological, and as Wikipedia says, became “increasingly dark and brooding [with] deceit and betrayal, particularly adultery” as primary themes.

The history of who “Patrick Quentin” was (and when) is a complicated one, and I’ll let the Wikipedia link suffice. For the book at hand, Puzzle for Players, as well as Fools, the authors were Hugh Wheeler and Richard Webb, the latter dropping out of the collaboration in the early 1950s.

Wheeler may be even better known as a playwright and librettist, rather than a mystery writer, and in fact in 1979 he wrote the book for the musical Sweeney Todd. This fact makes the author of the play that Duluth is putting on in Players rather remarkable, a chap by the name of Henry Prince. Harold Prince, of course, was the Broadway director of Sweeney Todd when it first opened. (The latter would have been 10 years old when Wheeler’s book was written, so the connection is either purely coincidental or pure prescience.)

Having been released from the sanitarium he was in while the events in Puzzle for Fools took place, along with his wife-to-be, Iris Pattison, Peter Duluth’s hopes for a full recovery depend on how successful this new play is going to be. What Duluth, a recovering alcoholic, does not expect, is that the all-but-abandoned theater where it will be opening may be jinxed, if not with real ghosts, then with figurative ghosts from the past.

Everyone in the cast seems to have their own demons of one sort or another: lost loves, thwarted loves, all-but-fatal accidents to recover from, new love affairs, and so on.

This is perhaps the most intense, and authentic, detective novel taking place in the world of the Theatre I can remember reading. Actors and actresses are good at leading the lies of other lives, so the theater and the detective fiction are well connected, but I cannot at the moment provide with a better example.

But as for Peter Duluth himself, he does a lot of thinking, but he really does no detective work himself. That chore is left to his (and Iris’s) psychiatrist, Dr. Lenz, and Inspector Clarke (who also may have appeared in the first book) who do the heavy work.

The final scene, in which the play is going on for the first time, in spite of a substitution for the leading man at the very last minute, while Lenz is attempting to go through the facts behind the killings and who the killer is — whew — really a high-powered juggling act on the part of the author, as well as the ultimate in a mind boggling mystery on the part of the reader.

Highly recommended.

PostScript. Throughout the book, I wondered who I’d cast as Peter and Iris if the book were to be turned into a film.

In the comments following Marv Lachman’s review of Fools, David Vineyard provided the following information:

“The Duluths made it to the screen in The Black Widow as Van Heflin and Gene Tierney [as Peter and Iris Denver]; in The Female Fiends (Strange Awakening) based on Puzzle for Fiends as Lex Barker and Monica Grey (called Peter and Iris Chance); and in Homicide for Three based on Puzzle for Puppets played by Warren Douglas and Audrey Long.”

In reverse order, then: Warren Douglas and Audrey Long — I can’t recall their faces well enough to say yea or nay. Lex Barker and Monica Grey — definitely not the former and I’m rather vague on the latter. Van Heflin and Gene Tierney — any movie with Gene Tierney in it is more than OK.

But while I was reading the book, I was pulled toward Ray Milland as Peter in one sense — the recovering alcoholic concept made him come to mind right away — but no, for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on, he’s not quite right.

For other reasons I also can’t explain and don’t laugh, I somehow had Robert Sterling and Anne Jeffreys in mind. (You probably know them best later on as the two lead stars in the comedy TV series Topper.)

Not that there’s anything remotely comedic about Puzzle for Players, and who knows how one’s unconscious mind works, but there you are.

Tue 21 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Newell Dunlap & Marcia Muller:

PATRICK QUENTIN – A Puzzle for Fools.

Simon & Schuster, US, hardcover, 1936. Victor Gollancz, UK, hc, 1936. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #83, 1940, with several later printings; Dell D192, Great Mystery Library #4, 1957; Ballantine F461, 1963; Avon PN238, 1969, with at least one later printing. Trade paperback: Penguin Classic Crime, 1986.

Patrick Quentin is a pseudonym of the collaborative team of Hugh Wheeler and Richard Wilson Webb — who also wrote as Quentin Patrick. From 1936 to 1952, the pair produced a series of successful novels featuring Peter Duluth, a former Broadway producer and recovering alcoholic, and his wife, Iris.

After 1952, Wheeler went on alone to write seven more novels under the Quentin name, four of them featuring a New York police detective, Lieutenant Timothy Trant (who also appears in novels by Wheeler and Webb under the Quentin Patrick — or, in the original editions, Q. Patrick — pseudonym).

The novels are well written and well characterized, and frequently the plots are as baffling as the pseudonyms under which they were created. The endings of these novels, be they as by Patrick Quentin or vice versa, are sure to both surprise and satisfy the fan of traditional mysteries.

A Puzzle for Fools opens in the expensive sanatorium where Peter Duluth has gone to dry out. Bad enough to be in a mental hospital, doubting your own sanity and the sanity of those about you, but what if you also begin hearing a voice whispering to you at night? And what if that voice sounds remarkably like your own? And what if that voice warns you to get away, for there will be murder?

This is Duluth’s plight. However, instead of doubting him, the director of the clinic believes every word and asks for his help in solving not only this particular puzzle but also several other strange goings-on around the clinic. Thus does Duluth become a sort of Sherlock Holmes at work in a mental institution.

Certainly Duluth, and the police, have their work cut out for them, because soon the whispering prophecy comes true and one of the staff members is murdered, only to be followed by the murder of one of the patients. This, of course, is a rich and fertile field for the whodunit, and Quentin handles it well; not only must all the patients be considered suspects, but all the staff members as well. And there are secrets to be discovered on both sides.

Other complex “puzzle” mysteries starring Peter Duluth include Puzzle for Players (1938), Puzzle for Puppets (1944), and Puzzle for Fiends (1946).

Among the novels featuring Lieutenant Timothy Trant are Death for Dear Clara (1937) and Death and the Maiden (1939), both as by Q. Patrick; and My Son, the Murderer (1954) and Family Skeletons (1965). Wheeler and Webb also wrote a series of mysteries under the pseudonym Jonathan Stagge.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright � 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: For another review of this book, see the one by Marv Lachman posted here not so long ago.

Tue 21 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

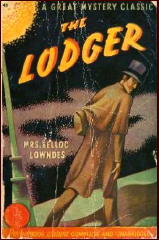

MARIA BELLOC LOWNDES – The Lodger.

Methuen, UK, hardcover, 1913. Scribner, US, hc, 1913. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including: Readers Library, UK, hc, 1927 [1st UK Photoplay edition]; Pocket 43, US, pb, 1940. (Both shown.)

I like to spend Octobers reading spooky stories and watching old monster movies, and I kicked off a past one with a good’un, Maria Belloc Lowndes’ 1913 novel, The Lodger.

The mystery of Jack the Ripper was a generation old when this was written, and it’s been done to death ever since, but Lowndes brought a sensitivity and feeling to it I found quite surprising.

The story is told primarily from the point of view of a landlady in dire straits who lets her upstairs apartment out to a well-paying gentleman. Her lodger seems to spend his days studying the Bible, and his rare evening excursions are invariably followed by news of another ’orrible murder.

All pretty standard so far, but Lowndes puts some real work into the Landlady’s reaction to all this: the more convinced she becomes that her lodger is a mad killer, the more she pities his torment and remembers the debt she owes him for saving her family from the Poor House.

Meanwhile, the Police blunder about, her loving husband worries over her nerves, and her step-daughter becomes the innocent cause of … well that might be giving something away. Suffice it to say that The Lodger is old-fashioned in spots but never seems dated, and it has the kind of atmosphere and characterization that reward reading.

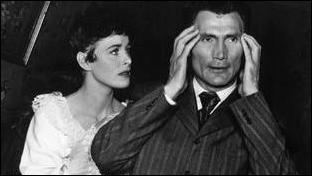

Incidentally, The Lodger has been filmed several times, including once as a silent film by Alfred Hitchcock, considerably changed, and more faithfully by 20th Century-Fox in 1944.

The Fox film is artfully done, and well-acted, if rather stodgy, but conveys none of the feeling of Lowndes book. Laird Cregar delivers an intense, sotto-voce performance, as opposed to nominal hero George Sanders, who looks as if he might die of Boredom (which he did, years later).

The same script was re-shot by Fox in 1954 [as Man in the Attic] to no great effect, with flat direction from Hugo Fregonese and a surprisingly listless performance from Jack Palance.

« Previous Page — Next Page »