December 2009

Monthly Archive

Sat 12 Dec 2009

DAVID OSBORN – Murder on the Chesapeake. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1992; Paperback reprint: Zebra; 1st printing, May 1993.

I don’t much care for prologues, as some of you may recall, and after reading the one in this book, it was very nearly all I read. Kids get murdered often enough in real life that they don’t have to get murdered in mystery stories too — if that’s all it is, a mystery story.

Or to be more specific: A young teen-aged girl is murdered in the prologue of this book, strangled and thrown off a balcony with a rope around her neck. And in some detail.

She’s a student in one of those exclusive preppy girls’ schools whose inhabitants love to torment the weaker of the species, and that’s the kind of life Mary Hughes led. Poor but intelligent and talented. No wonder she never fit in.

After an investment of $3.99 into the paperback edition, it’s tough to give upon a book after only 14 pages, and so, no, I didn’t quit.

As a writer, though, David Osborn bites off a bit more than he should have, I think. Telling the story is his leading character, Margaret Barlow, a sporty 55, a grandmother of a teenager, and a hot air balloonist, among other things that fall into the category of larger than life.” Her granddaughter, who calls her Margaret, is also a student at Brides Hall.

Nothing much else happens until page 164, on which a second murder is discovered. It’s a messy one — the victim is found sliced in half by an elevator, “dragging out her intestines and eviscerating her but unable to pull all of her down… ”

Come on. Who needs this? The rest of the detective story is weak, but I found this scene — let me speak plainly here — absolutely useless. Tasteless and trite — it’s a tough combination.

– This review first appeared in

Deadly Pleasures, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 1993 (very slightly revised).

Bibliographic Data: While David Osborn wrote a number of other books which are included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, including Open Season (1974), which was made into a film starring Peter Fonda, John Phillip Law and Richard Lynch, Margaret Barlow was his only series character.

The Margaret Barlow series:

Murder on Martha’s Vineyard (n.) Lynx, hc, 1989.

Murder on the Chesapeake (n.) Simon, hc, 1992.

Murder in the Napa Valley (n.) Simon, hc, 1993.

Sat 12 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

RUFUS KING – Museum Piece No. 13. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1946. Reprint paperback: Bantam , 1847, as Secret Beyond the Door. Film: Universal International, 1948, as Secret Beyond the Door (with Joan Bennett & Michael Redgrave; director: Fritz Lang).

Bantam Books describes this novel accurately as “suspense.” A wealthy widow is cajoled into a frenzy or falls in love at first sight, or something like that, with a publishing tycoon, himself a widower.

She apparently feels that he will be like her first husband, a dedicated coupon clipper who devoted himself to her.

Her bankers, who cannot turn over her money to her unless she marries a suitable man — for which read “rich” — hurriedly give their imprimatur, though the tycoon would have been found to be in dire need of a fresh infusion of cash to keep his newspaper going if they had investigated a bit more thoroughly. She, with substantial wealth, would appear to have no lawyers to advise her.

After the whirlwind courtship — time not specified, but it probably was no more than a month, and possibly less — he marries her and leaves the next day on a business trip. (No information is given whether the marriage was consummated. I’d tend to think it wasn’t.)

The tycoon collects rooms in which murders have taken place, buying them and moving them to his mansion intact, apparently even to the dust that was present at the time he bought them. Although the tycoon delights in giving tours of his collection, he does not allow a thirteenth room, recently finished, to be viewed by anyone.

It is obvious that the man is interested only in his new wife’s money, and even she dimly begins to recognize this when she moves into his home with his strange sister, brother-in-law, secretary who wears a veil to cover a scar that doesn’t exist, neurotic son, and a an egocentric star reporter.

Acting on advice of a psychiatrist who is making judgments on the woman’s quite limited and mostly wrong knowledge of the tycoon and on almost no knowledge of the woman, the tycoon’s new wife checks out room No. 13.

Although her husband, when he’s around at all, and the household are often out during the day, she needs must select 4 a.m. for her trip to the mysterious room.

King’s writing style is sometimes convoluted: “Both parents having been of the old-fashioned school which brooked no trifling with the mathematical gymnastics of the marriage vows in adding one to one and getting one, with all the sum’s attendant surfeiture of the unpictorial effects of contiguity and general minor inconveniences. Like when you wanted to read at night. Or when you didn’t.”

There are those who will master that at first reading. I am not one of them. But if you like that sort of thing, and I admittedly do, there’s a fair amount of it here.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 5, Sept-Oct 1987.

Fri 11 Dec 2009

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

MARTIN PORLOCK – X v. Rex . Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1933. US title: Mystery of the Dead Police, as by Philip MacDonald. Doubleday Crime Club, hc, 1933. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback, including Mayflower Dell, UK, 1965, and under the US title by Pocket #70, pb, 1940; Dell D247, pb, 1958 (Great Mystery Library #19); Macfadden, pb, 1965.

Films:

● The Mystery of Mr. X. MGM, 1934. Robert Montgomery, Elizabeth Allan, Lewis Stone, Henry Stephenson. Screenplay by Philip MacDonald. Director: Edgar Selwyn.

● The Hour of 13. MGM, 1952. Peter Lawford, Dawn Addams, Roland Culver. Director: Harold French.

Philip MacDonald was one of the great farceurs of the Twenties classic detective novel whose crimes were often cleverer than the solutions of his sleuth Anthony Gethryn. But as the thirties came along MacDonald added a new element to his books, along with the clever crimes he added a strong line of suspense that makes his books from this period among the most readable of their kind.

X v. Rex is the story of a serial killer (before the term serial killer was in use) — one who is targeting the police themselves (Rex referring to the Crown), his targets constables on their beat, his method disguise and brilliant innovation (for instance he uses a sandwich board to hide the gun with which he kills one unsuspecting victim).

Scotland Yard is up in arms, and the streets have become places of fear. With all this activity, it is practically impossible for a criminal to sneeze without being arrested.

Still X strikes with impunity, and as the police tighten their cordons and expand their hunt London is becoming as unsafe for the average crook as for the unlucky constables X hunts and kills.

Nicholas Revel is no ordinary crook, but he’s feeling the pinch. Revel is a gentleman cracksman in the Raffles mold, suave, careful, and recently finding it difficult if not impossible to pursue his career.

Clearly the only way to remedy this situation is to stop the deadly X, and if the police can’t do it, perhaps Nicholas Revel with his unique perspective can.

But in order to find X, Revel needs access to information only the police know, so he romances the daughter of a high ranking police official and casually makes a few “suggestions” based on things he has learned from his underworld connections.

The police aren’t entirely sure they trust young Mr. Revel, but his contacts do get him closer so that he can begin his own hunt for X. The suspense builds as Revel must put his own life on the line in the garb of a London bobby to spring the final trap for X, even as the police close in on the madman.

X remains little more than a mysterious madman. Little or no effort is made to explain why he is pursuing his deadly war on the police, and why the most vulnerable and common of all British policemen, the bobby. That isn’t MacDonald’s interest. Instead he gives us the tensions of the hunt, the almost inhuman cleverness of X, and Revel’s clever schemes to get into the good graces of the police and their suspicions about his insights into the mystery of X.

X vs Rex is one of the sprightlier examples of its type from the Golden Age of the Classical Detective novel. MacDonald would later combine the lessons learned here in two of his best Anthony Gethryn novels, The Nursemaid Who Disappeared (aka Warrant for X) and The List of Adrian Messenger.

Both of the latter two books have been filmed, Nursemaid twice, the second time as Henry Hathaway’s 23 Paces to Baker Street), but X v. Rex may be his happiest confluence of Classic Detective novel and Suspense Thriller other than his earlier 1931 novel Murder Gone Mad.

X v. Rex was filmed twice, the first time excellently with a screenplay by MacDonald himself (who went on to have a long and successful career as a screenwriter working on everything from Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto to Alfred Hitchcock’s film of Rebecca).

Robert Montgomery was perfectly cast as Revel, Elizabeth Allan the lady in question (she became Mrs. Montgomery in real life and their daughter the actress Elizabeth Montgomery), and Lewis Stone and Henry Stephenson as suspicious policemen. The film is atmospherically done with a rousing finale.

It was remade as The Hour of 13, which is inferior, but nonetheless the film has a solid performance by Peter Lawford as Revel and moves the setting from the contemporary London of the novel and first film to the late Victorian earlier Edwardian era to some effect. It’s by no means a bad film, just not equal to the original.

X v. Rex is dated and readers used to the more psychological emphasis of this sort of novel may find it shallow in comparison, but it is a highly entertaining read by a master of the form with a well done portrait of a city under siege by a mad killer and the almost military precision of the hunt for the killer.

Nicholas Revel is a charming rogue presented as a surprisingly believable gentleman criminal, and if the finale is a bit of a let down (the one in the films is not) it is only because MacDonald has pulled out all the stops in his clever manhunt.

This one is a keeper, as enjoyable the second or third time around as the first.

Fri 11 Dec 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE HOODLUM. Pickford/First National, 1919. Mary Pickford, Ralph Lewis, Max Davidson, Kenneth Harlan, Melvin Messenger. Photography: Charles Rosher; art director: Max Parker. Director: Sidney A. Franklin. Shown at Cinecon 40, Hollywood CA, September 2004.

I have been told that William K. Everson considered this to be Pickford’s best film and I wouldn’t disagree with that assessment.

Pickford plays a poor little rich girl who lives with her grandfather in a mansion while her sociologist father is away.

When she decides to go live with her father in the ghetto where he is gathering material for a book, she quickly adapts to her new life, turning into a street kid and making friends throughout the neighborhood.

She also befriends a lonely man who had worked for her grandfather and had gone to jail for financial misdealings for which he was not responsible. Learning that papers that will clear him are in a safe in her grandfather’s house, she helps him break in and retrieve the documents, only to be surprised by the police and her equally surprised grandfather.

The ghetto set was designed by Max Parker and is a marvelous setting for the multiple story lines in this endearing film. Pickford was never better, playing a gamut of roles that culminate in her coming-out as a young woman and, finally, a bride.

Editorial Comment: Obviously, then, the photo above comes from the end of the movie, not the middle or beginning. That’s Kenneth Harlan with Mary, in case you didn’t recognize him!

Fri 11 Dec 2009

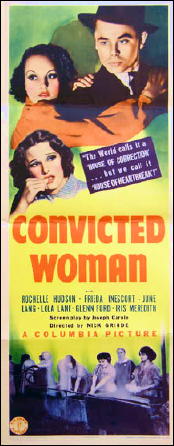

CONVICTED WOMAN. Columbia Pictures, 1940. Rochelle Hudson, Frieda Inescort, June Lang, Lola Lane, Glenn Ford, Iris Meredith, Lorna Gray, Esther Dale. Director: Nick Grinde.

Following Walter Albert’s review of Women’s Prison (Columbia, 1955) reviewed here not too long ago, Walker Martin pointed out that there is a whole subgenre of WIP movies, where for the uninitiated (me) WIP is an acronym for “Women In Prison.”

I have no idea what the first movie in the category was, but I’m sure someone can easily tell me. At the moment, I’m assuming that this was an early one, but perhaps I’m wrong.

And I do and I don’t know exactly what the attraction is, and I think that is all that I am going to say about that. I suppose there may even have been entire articles and perhaps even books dedicated to the subject, and if there are, someone can tell me about those also.

Rochelle Hudson plays Betty Andrews, a young woman who’s sent to prison for a crime she didn’t do, and with a wrong attitude from the get-go (well, wouldn’t you?), she starts out badly and (nearly) ends up worse. Chief Matron Brackett (Esther Dale) does not believe in coddling her prisoners, and for a couple of inmates (June Lang and Lorna Gray), her wishes are their commands.

But after one girl, tormented too long, commits suicide, reform comes, but the former regime does not intend to go down without a fight. Luckily Betty has help on the outside in the form of an impossibly young Glenn Ford, a reporter who’s been working on her behalf from the beginning.

Even though it’s short, just over an hour long, I found no difficulty in watching this movie in two or even three installments, which tells you one thing, but the fact that I came back to watch it all the way through, that may tell you something else.

Naturally it all ends well, but real prison reform is nothing but a pipe dream that never seems to last very long. Why else would there be a whole category of movies just like this one that came along later, with Ida Lupino in at least two of them?

Thu 10 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

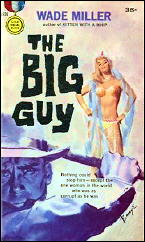

WADE MILLER – The Big Guy. Gold Medal #279, paperback original, 1st printing, January 1953; second printing: Gold Medal s936, 1969.

Wade Miller was the joint pseudonym of a couple of high school buddies who teamed up to write mysteries all their adult lives, with astonishingly successful results. Astonishingly, because their books were almost without exception flat, trite and predictable.

And their work under the pen-name Whit Masterson is even worse; reading Badge of Evil is an onerous chore indeed for anyone charmed by the grace and energy of the film Orson Welles managed to make from it (Touch of Evil, Universal,1958.)

I can speak from experience on the breadth and depth of Wade Miller’s ineptitude because I searched out those books avidly, back in college, after reading what turned out to their one decent effort, The Big Guy. What burst of inspiration was responsible for this I couldn’t say, but it’s fast, hard and even fun in a sick, predictable fashion. Like watching a really bad accident when you can’t look away.

Big Guy follows the rise and rise of Joe Drum, a low-class, no-brains strong-arm man imported to L.A. for a little muscle, who sees a chance to move into the big time and takes it. And keeps on taking.

Miller borrows a lot from films like Scarface, and Little Caesar, but the writing is fast, the violence edgy and often surprising, and the story gets really going, in its own disturbing way, about halfway through, when Drum meets a woman who cures his sexual hang-ups, introduces him to comfort, culture, class and drugs, and generally makes a better person out of him — with results you can see coming a long way off, but I kind of enjoyed watching it all happen.

Miller introduces a couple of subtle touches you don’t see in a Wade Miller book, and shows sense enough not to call attention to them —nothing’s worse than pointing out how subtle you’re being.

Back in College this really impressed me, as I say, and I followed it up, or tried to, with some other Millers, till I found I was squandering my precious youth on a writer (writers, rather) who had only one good book between them.

Editorial Comment: For much, much more on the authors who were Wade Miller, including loads of reviews and an interview with Robert Wade by Ed Lynskey, Bill Pronzini and myself, go here on the main Mystery*File website.

Thu 10 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

Reviewed by MIKE DENNIS:

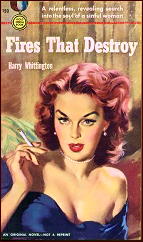

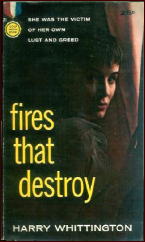

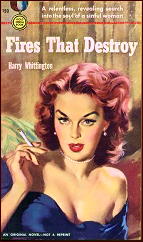

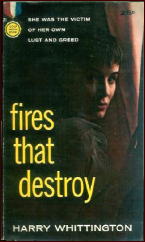

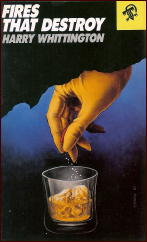

HARRY WHITTINGTON – Fires That Destroy. Gold Medal #190, paperback original; 1st printing, 1951; 2nd printing: #831, 1958. Reprint paperback: Black Lizard, 1988.

Some guys have all the luck. Blondes have more fun. You’ve heard the cliches. But at the faceless corporation where Bernice Harper works, pretty girls get all the promotions.

And it pisses her off.

That’s the central theme in Fires That Destroy, a tight little noir novel from 1951 by Harry Whittington.

Year in and year out, she watches through her thick-lensed glasses as sexy babes in tight skirts use their attributes to glide effortlessly up the ladder while Bernice, plain and stringy-haired, stays mired in the steno pool.

She builds up a reservoir of resentment, which eventually morphs into self-hatred when her boss recommends her for the position of private secretary in the home of an important client. Problem is, he’s blind.

She knows they foisted her off on a blind man, almost as a joke, and she doesn’t like it. Things are made worse when she learns he’s a heavy drinker who never tires of making passes. This intensifies her hatred, as she knows that he wouldn’t come near her if he could see.

And so begins her descent into hell.

The novel actually opens with Bernice looking down a staircase at the blind man’s twisted corpse. She’s just pushed him down the stairs to his death. In the dark silence of the house, a grandfather clock chimes, freaking her out. She thinks, “The sound of a clock and I’m paralyzed. How will I stand the rest of it?”

Not very well, actually. Whittington ratchets up the stakes for Bernice in nearly every scene. But she’s so consumed by her hateful obsession with the world she inhabits that she can’t rescue herself. Her unraveling forms the spine of the story.

In a masterful stroke, Whittington takes the reader deep into Bernice’s mind, as she slowly disintegrates into “the most depraved and sinful woman on the face of the earth.” Her interior dialogue with herself evokes Jim Thompson at his most dangerous.

Whittington wrote over 170 novels in his astonishing career, hopping around through various genres. Most of his work, unfortunately, is out of print, but noir aficionados should make a point of locating a copy of Fires That Destroy.

Copyright © 2009 by Mike Dennis.

Wed 9 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

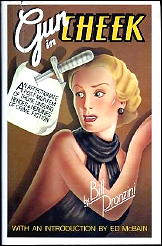

BILL PRONZINI – Gun in Cheek: A Study of Alternative Crime Fiction. Coward McCann & Geoghegan, 1982, hardcover, 1982. Trade paperback: Mysterious Press, 1987.

CONTENTS:

Introduction by Ed McBain (Evan Hunter)

“Without Malice, A Forethought” by Bill Pronzini

1. Wanna Woo-Woo?

“Someone standing inside the body of the black cat would be able to fire a revolver through its mouth!”

2. The Eyes Have It

“He was dead, all right. He had been shot, poisoned, stabbed, and strangled. Either somebody had really had it in for him or four people had killed him. Or else it was the cleverest suicide I’d ever heard of.”

3. Cheez It, the Cops!

“Since when did you get around to using all those two-syllable words?”

4. The Saga of the Risen Phoenix

“A sudden thought bounced her heart to her larynx.”

5. The Goonbarrow and Other Jolly Old Corpses

“In plain English, Patterson,” said Pye, “nix on the gats!”

6. Dogs, Swine, Skunks, and Assorted Asses

“And here I slave over a hot tommygun all day!”

7. C-H-I-N-K-S!

“Think of it! A pretty girl to cuddle up to on cold nights and her shirt-tail to keep your feet warm. Bully, my boy, bully! Maybe a couple of little dingy-dingies coming along to call you ‘papa’.”

8. The Vanishing Cracksman, the Norman Conquest, and the Death Merchant

“The vicissitudes of a capricious fate are indeed inconsistent and incommensurable!”

9. In the Name of God — WHOSE HAND?

“Your toe went up the staircase?”

10. The Idiot Heroine in the Attic

“In the warm glow of happiness that enveloped her, the caption on the billboard did not strike her as even faintly ominous. It said, “Fly Now — Pay Later’.”

11. Don’t Tell Me You’ve Got a Heater in Your Girdle, Madam!

“My jaw bounced off the back of my skull and I wallowed in the softness of a cloud. I groped around for my brain and after a couple of years it came back from San Francisco and said ‘Get up!'”

12. Ante-Bellem Days; or, “My Roscoe Sneezed: Ka-chee!”

“Drop that corpse, you fool!”

Editorial Comment: Thanks to Mike Tooney for providing the quotes. We both believe that if you’ve read this post without cracking up out loud at least three times, you ought to see a doctor.

Wed 9 Dec 2009

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

BILL PRONZINI – Gun in Cheek: A Study of Alternative Crime Fiction. Coward McCann & Geoghegan, 1982, hardcover, 1982. Trade paperback: Mysterious Press, 1987.

Gun in Cheek is Bill Pronzini’s backhanded salute to the “Best of the Worst,” books and stories that pushed the envelope of language to the breaking point and beyond. The blurb on the back says it all:

Gun in Cheek is … a delightful exploration of what the author refers to as “alternative crime fiction.” Less kindly put, it is a unique crash course in the worst English and American crime fiction of the twentieth century.

Every category of mystery fiction is represented: the private eye, the stately home, the arch-villain, the gentleman sleuth, the amateur spy, and many others who have blossomed from the genre.

Within these categories, in what can only be called a labor of love, Bill Pronzini discusses, digests, and shares the best of the worst — adding a wonderfully comprehensive bibliography for advanced and dedicated devotees.

Gun in Cheek is an amusing and pleasurable reading experience as well as an enlightening guide to hardboiled potboilers.

But they’re not all hardboiled. Gladys Mitchell is Pronzini’s target in Chapter Five: “…Mitchell’s prose is of the eccentric variety, to put it mildly — something of a cross between Christie and P. G. Wodehouse, with a dollop or two of Saki, or maybe John Collier, thrown in — and, like garlic and rutabagas, is an acquired taste.”

Of course, Pronzini’s criticism is supported by only one example: The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop. Nevertheless, as Ed McBain (Evan Hunter) says of Pronzini in his Introduction, “He has obviously read and digested everything ever written in the genre by anyone anywhere,” so his judgment in these matters is to be respected.

Gothic mysteries are examined in Chapter Ten, which begins with a famous Donald Westlake quote: “A gothic is a story about a girl who gets a house”; but the variations rung in on the Gothic theme can go far afield, as Pronzini amply demonstrates.

Ed McBain feigns injury in the Introduction, wounded by Pronzini’s ignoring some of the bad writing McBain himself was guilty of, and produces examples of his own as proof that even the best writers can nod now and then over their typewriters — and what does this say about editors?

Pronzini discusses some works at great length, such as (in Chapter Seven) The Dragon Strikes Back by Tom Roan (1936), an extravaganza so over the top that it leaves Pronzini wishing its author had produced more of the same.

(If Ian Fleming ever denied having cribbed from The Dragon Strikes Back when he wrote Dr. No, he must have been lying, especially with its element of a renegade group trying to initiate a world war among the superpowers — how many times have those drearily formulaic Bond films used that very notion?)

Chapter Four affectionately deals with Phoenix Press, whose stable of “alternative” authors boggles the mind, and among whom was Harry Stephen Keeler, “the once-popular ‘wild man’ of the mystery, who seems to have been cheerfully daft and whose plots defy logic and the suspension of ANYONE’S disbelief.”

(Sidebar: Keeler offered his plotting schemes for sale to the public. That’s a lot like you teaching your cat Tiddles to play Chopin’s ‘Piano Concerto in F Minor’ : No matter how good he gets at chording, his feet will never reach the foot pedals — and Keeler’s “feet” never did.)

You’ll probably enjoy Gun in Cheek, but three cautions:

● One (for parents): There is some coarse language.

● Two: Spoiler Alerts, for Pronzini happily reveals the endings in a few cases.

● Three: Don’t try to read this book in one sitting because it just might make you dizzy — with laughter.

Wed 9 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

J. G. BALLARD – Running Wild. Hutchinson, UK, hardcover, 1988. Farrar Straus Giroux, US, hc, 1989; trade ppbk, April 1999.

J.G. Ballard might be called science fiction’s poet of the apocalypse. His stunning early science fiction novels, The Wind From Nowhere, The Drowned World, The Drought, and The Crystal World were like nothing anyone else had written and nothing readers had encountered.

He had taken the Wellsian science fiction novel as practiced by John Wyndham and John Christopher and carried it about as far as it could go.

He followed that with stunning novels that have no real genre but their own, Concrete Island, High Rise, and Crash among them.

Running Wild was his first crime novel, and as stunning and apocalyptic as his science fiction. The book is a mere 88 pages long and should not be difficult to find.

Shortly after 8 o’clock in the morning on June 25th, 1988 the “Pangbourne Massacre,” as it came to be known in the press, took place. All 32 adult residents of the exclusive gated community just West of London were murdered, and the children have gone missing, presumed abducted. Is it a work of a madman, terrorism, or something worse?

Dr. Richard Greville the Deputy Psychiatric Advisor to the Metropolitan Police is called in to lead the investigation, but what he uncovers is at first more puzzling than the crime itself and gradually too horrible to face:

I can only plead that what now seems self-evident scarcely seemed so at the time. My failure to recognize the obvious, in common with almost everyone else concerned, is a measure of the true mystery of the Pangbourne Massacre.

Ballard’s protagonist investigates the crime and begins to dissect it with care as the horrible truth begins to dawn on him. Like Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Running Wild is the rare mystery where the solution is more horrible than the crime itself.

Told in a cool clinical style, the short novel build to a tremendous power. Even once you start to grasp the truth, you may, like the officials at the end of the novel, reject it as just too horrible to face.

Perhaps one line of the novel sums up Ballard’s theme and his point:

In a totally sane society, madness is the only freedom.

Edgar Allan Poe said something very like that when he observed that madness might be the highest form of sanity. Like Poe, Ballard has written a work about the dark corners of the human psyche, and the evil men do with the best of motives and in the name of the greatest kindness.

Before his recent death Ballard wrote at least two more crime novels , Cocaine Nights and Super-Cannes. Both are superior works, but neither is the stunner this one is.

Few horror novels can claim to have the impact of this compellingly clinical novel about an unthinkable crime, one that has been all too prescient in light of terrors in our own modern world.

The frights of Ballard’s short novel are more potent than any witches, werewolves, or vampires — they are the everyday terrors that are the all too real stuff of the nightly news.

« Previous Page — Next Page »