July 2010

Monthly Archive

Mon 26 Jul 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Francis M. Nevins:

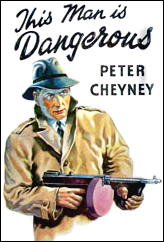

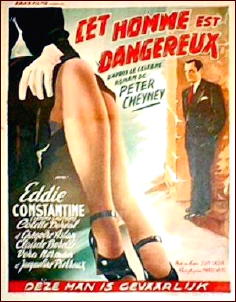

PETER CHEYNEY – This Man Is Dangerous. Coward McCann, US, hardcover, 1938. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1936. Reprinted many times in paperback. Film: Sonofilm, 1954, as Cet Homme Est Dangeureux (This Man Is Dangerous) (with Eddie Constantine as Lemmy Caution; director: Jean Sacha). Released in the US as Dangerous Agent.

Peter Cheyney (1896-1951) never visited the United States in his life and knew next to nothing about Americans, but in the late 1930s be became an instant success in his native England and in Europe, especially France, as a writer of fake-American hard-boiled novels.

In This Man Is Dangerous and ten subsequent titles, he chronicled the adventures of rootin’ -tootin’ two-gun-shootin’ Lemmy Caution, an indestructible FBI agent who downs liquor by the quart, laughs at bullets flying his way, romances every dame in sight, and blasts away at greasy ethnic-named racketeers – and (in the later novels) Nazi spies.

Americans, of course, saw these ridiculous exercises for what they were, and only the first few were ever published here. Certainly no one would read Lemmy Cautions for their plots, which are uniform from book to book — all the nasties double-crossing each other over the McGuffin — nor for their characterizations, which are pure comic strip.

But mystery fans with a taste for lunacy may be attracted by Cheyney’s self-created idiom. Lemmy narrates his cases in first person and present tense, a wild-and-crazy stylistic smorgasbord concocted from Grade Z western films, the stories of Ring Lardner and Damon Runyon, eyeballpoppers apparently of Cheyney’s own invention (like “He blew the bezuzus” for “He spilled the beans”), and a steady stream of British spellings and locutions.

Nothing but quotation can convey the Cheyney flavor. From This Man Is Dangerous:

I says good night, and I nods to the boys. I take my hat from the hall an’ I walk down the stairs to the street. I’m feeling pretty good because I reckon that muscling in on this racket of Siegella’s is going to be a good thing for me, and maybe if I use my brains an’ keep my eyes skinned, I can still find some means of double-crossing this wop.

From Don’t Get Me Wrong (1939):

Me — I am prejudiced. I would rather stick around with a bad-tempered tiger than get on the wrong bias of one of these knife-throwin’ palookas; I would rather four-flush a team of wild alligators outa their lunch-pail than try an’ tell a Mexican momma that I was tired of her geography an’ did not wish to play any more.

From Your Deal, My Lovely (1941):

Some mug by the name of Confucius — who was a guy who was supposed to know his vegetables — once issued an edict that any time he saw a sap sittin’ around bein’ impervious to the weather an’ anything else that was goin, an’ lookin’ like he had been hit in the kisser with a flat-iron, the said sap was suffering from woman trouble.

Lemmy Caution became so popular on the Continent that Eddie Constantine, an American actor, portrayed him in a series of French films. These films were so successful that Jean Luc Godard used Constantine as Caution in his New Wave film Alphaville.

Eventually Cheyney launched a second wave of novels, written in a spare ersatz-Hammett style and featuring Slim Callaghan, London’s toughest PI. But for those who love pure absurdity, and appreciate the wild stylistic flights of Robert Leslie Bellem and Henry Kane and Richard S. Prather, a treat of comparable dimensions is in store when they tackle the adventures of Lemmy Caution.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 25 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[18] Comments

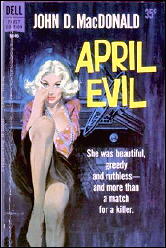

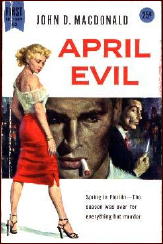

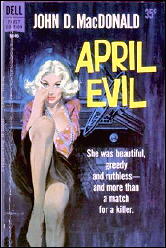

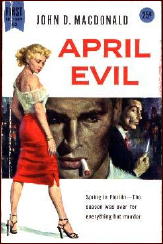

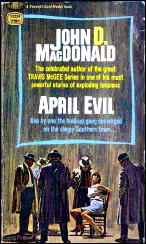

JOHN D. MacDONALD – April Evil. Dell 1st Edition B146; paperback reprint, May 1960. First printing paperback original: Dell 1st Edition 85; 1956. Reprinted later several times by Gold Medal, also in paperback, beginning with d1579, 1965.

A shorter version first appeared in Cosmopolitan (January 1956), back in the days when the magazine actually published stories worth reading. And so did Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, and The American Magazine, among others.

These were the magazines my grandparents bought. They lived next door to us, and when I went over to visit, which was often, that’s where and when I got my first exposure to slick literary fiction.

But since they didn’t get Cosmopolitan, I’m sure I missed this one when it first appeared. The earlier Dell printing was a paperback original, but the one I just finished reading is the one with the beautiful Robert McGinnis blonde on the front cover, with lots of leg showing as she’s seen sitting in the open passenger side of an automobile.

And do you know, whenever I’ve looked at the cover, with the blurb “She was beautiful, greedy and ruthless — and more than a match for a killer” I always thought the lady’s name was April. Not so. April is the time of year when a number of nasty elements of crime, passion and (yes) greed come to a nexus all in one spot: Florida, of course, and knowing JDM’s prediction for story settings, it goes almost without saying.

Lenora is beautiful, in an after-thirty on-the-edge sort of way. Blonde, with the sort of trimness in her figure that McGinnis so eloquently suggests. Greedy, yes again. Her soft, useless husband’s uncle is reclusive, extremely wealthy, and a bit of an eccentric, and if it were up to Lennie, the old man would be committed in an instant. Which also makes her ruthless — so the cover’s right. Three for three.

Is she more than a match for a killer? I won’t say, but I’ll let you guess. Lennie is not the only one with an eye for money, and Dr. Tomlin never did believe in banks. Three gangsters and a moll are also in town. MacDonald never uses the word “moll.” It was probably out of fashion even in 1955, but “faithful companion” isn’t quite the right the right phrase to describe Harry Mullin’s friend Sally Leon either.

More. Dr. Tomlin’s home is also now the residence of another distant relative and his wife, who came visiting and have been invited to stay. Hence Lennie’s extreme perturbation.

It is great fun to watch the pieces fall together — and I haven’t mentioned all of them — knowing ahead of time (almost) how they’re going to fit into place. Adding to the pleasure, MacDonald has a very acerbic attitude toward the type of people he dislikes, and even while being subtle, he doesn’t hesitate in letting it show. Flashy guys with only a facade; weaklings who jab around at life and can never deliver a telling blow; women with dreams who take only the easy path.

Who are the heroes in JDM’s world? Men with wives and children they love. Individualistic older men who take a shine to women who need shelter and nurturing. Soft men who show some backbone when it counts, even though it may be too late.

Under MacDonald’s unforgiving eye, the villains almost always get what they deserve, and the good guys? Maybe they do as well. Or maybe not. I’d hate to have you think that JDM’s world one in which everything necessarily comes out even and square and wrapped up nicely in a bow.

Sat 24 Jul 2010

A REVIEW BY MARYELL CLEARY:

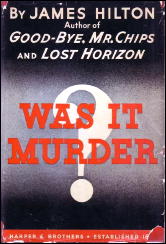

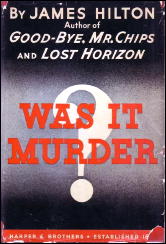

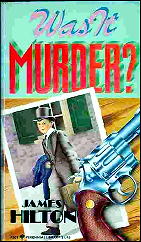

JAMES HILTON – Was It Murder? Paperback reprint: Bantam #29, 1946. Hardcover edition: Harper & Brothers, US, 1933. Other reprints include: Dover, trade paperback, 1979; Perennial Library, pb, 1980. First published as Murder at School, by Glen Trevor: Benn, UK, hardcover, 1931.

James Hilton’s only mystery is set in a boys’ school in England. It is interesting to compare it with Nicholas Blake’s mystery A Question of Proof, which has the same sort of setting. Both Hilton and C. Day Lewis, Blake’s real name wrote other kinds of literature and gained their primary reputation that way.

Blake, in his first detective story, gives us the picture of an entire school and its operations, while Hilton prefers to concentrate on one segment. Hilton shows us just a corner of the physical domain: the headmaster’s house, the home of one of the married masters, a dormitory, and glimpses of the chapel and the Circle, a path around the perimeter of the school.

His amateur detective, Colin Revel, is an “old boy” of Oakington, so it is not hard to find an excuse for his presence before there is widespread suspicion of murder.

Blake’s detective is called in by a master under suspicion after murder has very obviously been done. Yet both fit well into the schools, get along with masters and boys, and don’t seem out of place.

Revell is called in by the headmaster, Dr. Robert Roseveare when one of the younger boys is killed, apparently by acc1dent. Roseveare seems nervous, but as the investigation goes on and the accident seems to be precisely that, he is quite anxious to have Revell leave.

Then a second boy dies, a brother of the first, in another ‘accident.’ Revell hastens back; the police are called in by the boys guardian, and evidence is found that this time it is murder.

Suspicion naturally falls on the master, who inherits all the boys’ wealth. But there is no evidence. And there is a deathbed confession, and the police leave. But Revell is not satisfied and stays on.

The cast of characters is small; suspicion never goes far from the one person. There is less a hunt for evidence than a delving into the high emotions of the people: love, jealousy, greed, fear, pride.

Sophisticated readers of the 70s may guess the surprise solution before the end, but the writer keeps up the drama and the suspense; we can’t be sure. And when the final revelations come, they draw together all the skeins, and one puts down the book with a sigh of satisfaction.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 2, No. 6, Nov-Dec 1979.

Bibliographical Note: It is not quite true, perhaps, that this book was Hilton’s only mystery, as there are three others listed under his name in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. Two are included only marginally, however, and the third may be a crime story without being a mystery, per se. For completeness, though, here’s the complete list:

HILTON, JAMES. 1900-1954.

-Rage in Heaven (n.) King 1932

Knight Without Armour (n.) Benn 1933

Was It Murder? (n.) Harper 1933. See: Murder at School (Benn 1931), as by Glen Trevor.

-We Are Not Alone (n.) Macmillan 1937

Fri 23 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

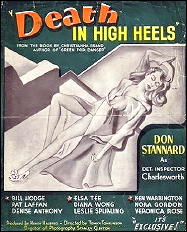

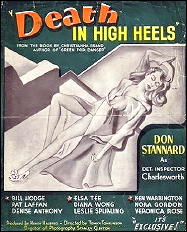

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Death in High Heels. John Lane/Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1941. Charles Scribner’s Sons, US, hc, 1942. Paperback reprints: Pan, UK, 1948; Carroll & Graf, US, 1989 (shown). Series character: Inspector Charlesworth. Film: Marylebone, 1947; with Don Stannard as Det. Charlesworth. Director: Don Stannard.

I found Christianna Brand’s ’prentice novel still quite enjoyable on my second reading. While the mystery plot is only mildly interesting, being not tremendously complex and but lightly clued, Brand does a fine job of keeping the reader hanging on to rapidly shifting suspicions and turns of events — a technique she beautifully perfected a few years later in her widely acknowledged masterpiece, Green for Danger. (One event here, though, rather melodramatically absurd, is hard to swallow.)

What I enjoy most about Death in High Heels is the setting, which is one of the best realized of the Golden Age period (if we stretch the usually accepted years of the Golden Age just slightly). The dress shop atmosphere, with its colorful coterie of ladies and men (along with designer Mr. Cecil, who is somewhere in between the two previously mentioned sexes), is strongly and amusingly conveyed.

The dumb stereotype of British Golden Age mystery — that all these books take place in upper-class country houses, posh London flats or highly stratified Cranford-style villages — certainly is belied by Brand’s first novel, which takes place in a hard-nosed London business establishment where most of the characters are working girls who by no means are economically well-settled.

Brand was such a “girl” and worked in such an establishment herself, I believe, which certainly lends authenticity to her setting in Death in High Heels.

Especially refreshing in Death in High Heels is the light badinage about sex. The ladies are breezily and pleasantly irreverent on this subject, while the presentation of Mr. Cecil and “the boyfriend” seems quite explicit for the time (even the most obtuse reader of the day must have recognized s/he was reading about a “gay” couple).

Unlike some of Ngaio Marsh’s portrayals of gay men from the same period, Brand’s presentation of the colorful Mr. Cecil, while admittedly comically broad, comes off, in my view, as genuinely amusing rather than merely demeaning. And each of the numerous dress shop ladies comes across as a distinct individual, a distinct achievement on the part of the author.

Though nearly seventy years old, Death in High Heels has dated not much at all. It’s one of the best “workplace atmosphere” mysteries of the period, I believe.

Editorial Comment: The crime fiction of Christianna Brand has been reviewed several times on this blog. Most recently was Marcia Muller’s review of Green for Danger, from 1001 Midnights. Following this link will lead you to that review, which in turn contains links to four earlier reviews.

Fri 23 Jul 2010

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

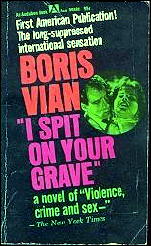

BORIS VIAN – I Spit on Your Grave. First US edition: Audubon, paperback, 1971. Canongate Edinburgh, Scotland, pb, 2001. Reprinted as I Spit on Your Graves: Tamtam Books, softcover, 1998. Translation of J’Irai Cracher Sur Vos Tombes, as by “Vernon Sullivan,” France, 1947.

Film: Audubon, 1962, as J’iral Cracher Sur Vos Tombes (I Spit on Your Grave). Christian Marquand, Antonella Lualdi, Paul Guers, Renate Ewert, Jean Sorel, Fernand Ledoux. Director: Michel Gast.

Somewhere along the way last month I read Light in August, which I don’t propose to review here because Faulkner don’t need me to pimp for him. But it led me to read another two-bit paperback, obviously inspired by Faulkner’s work, I Spit on Your Grave.

Grave was published in France in 1946, when the public there was crazy for American hard-boiled books and movies (unavailable there since 1940) and would apparently devour anything that looked appropriately tough and western, including palpable fakes like Lemmy Caution and James Hadley Chase — I digress, but it explains how I Spit on Your Grave was promoted as a French translation of an American book, when in fact it was written by one Boris Vian, who was about as American as Pepe le Pew.

Surprisingly, though, this is quite well done. The nameless narrator, a black man passing for white (like Joe Christmas in Faulkner’s book) sets us somewhere in the southern U.S. and tells of his quest for vengeance for the lynching of his brother. Said vengeance becomes a nasty bit of business as the narrator insinuates himself into a small town and works his way around to seducing the daughters of the local rich folk — with a view to something even worse to come…

Vian ain’t no Faulkner, but that’s not always a bad thing; he evokes the small town colorfully, his prose is sharp and well-judged and the tone is pleasingly nasty, veering toward the pornographic as the narrator exacts his baroque retribution. And I should warn you that this book contains graphic violence one seldom encounters even now in mainstream books.

The book itself had an interesting history: when a copy was found near the body of a murdered woman (with significant passages underlined) the publishers were charged with pandering obscenity and the true story of its writing emerged.

This only made it more popular, and it was filmed in 1959. The movie is a low-budget affair that runs out of steam somewhere along the way and softens the ending, but it evokes the dusty desperation of a one-whore town surprisingly well for a film made entirely in France and cast with badly-dubbed French actors.

I liked it myself, but there’s a story that Vian went to a preview, screamed “What is this sh*t?!” and fell over dead.

It’s a nice story, anyway.

Editorial Comment: Most sources state the date of the French edition as 1946, as does Dan. The year 1947 that I stated in the opening credits is that as given by Al Hubin in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. He’s on a vacation cruise right now, but I’ll ask him to help sort out this small disparity when he gets back.

Thu 22 Jul 2010

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marv Lachman

EARL BARGAINNIER, Editor – Comic Crime. Popular Press, hardcover, 1987; trade paperback, 1988.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 10, No. 2, Spring 1988.

As the title implies, this collection of essays deals with comedy in the mystery and is the first book on the subject in my memory.

It is also one which is far-reaching, covering humor in the Sherlock Holmes canon (Holmes and Watson were really the first “Odd Couple”), the academic mysteries, in mysteries set in quaint little villages, and in those featuring little old lady and gentlemen detectives.

Even the hardboiled mystery gets its due in “Laughing with the Corpses,” by Frederick Isaac. Unfortunately, Craig Rice is virtually ignored throughout, but there is an excellent piece on Donald Westlake by Michael Dunne.

There are fourteen essays in the book and not a bad one in the lot. Some.of the examples the authors quote will make you laugh again if they are familiar; others will make you want to seek out the books from which they were taken.

Editorial Comment: This is the sixth in a series of reviews in which Marv covered reference works published in 1987, books about the field of mystery and crime fiction. Preceding this one was Corridors of Deceit, by Peter Wolfe. You can find it here.

Thu 22 Jul 2010

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

SHIRLEY TALLMAN – Scandal on Rincon Hill. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, March 2010.

Genre: Historical mystery. Leading character: Sarah Woolson; 4th in series. Setting: San Francisco, 1881.

First Sentence: The nightmare began early on the morning of Sunday, December 4.

Sarah Woolson is only the third female attorney to be licensed in California and is struggling to get her private practice off the ground.

A brutal murder occurs on Rincon Hill, near her home, followed shortly by a second murder. Neither victim had been robbed. Both had attended the same party. Two young, very recently immigrated Chinese men are arrested, Sarah’s former client, powerful tong leader Li Ying, hires her to prove their innocence.

At the same time, Sarah is hired by beautiful young woman. She had a written contract with a morality-touting publisher to be his private mistress. When she became pregnant, within that time, he cut off all support. Now, she wants Sarah to sue him.

Ms. Tallman skillfully takes the reader back to 1881, pre-earthquake San Francisco. She creates a solid sense of the places, styles and attitudes of the time. She particularly illustrates the bigotry against the Chinese.

Living in the Bay Area, it is particularly fun for me to read about locations I know and her descriptions of food are delectable. I do wonder, however, whether those who don’t know San Francisco might feel a bit lost and wished a map or photos had been included.

The dialogue, which reflects the syntax of the period, adds to the sense of time and provides an indication of each characters social status. For those who’ve not read prior books, enough background is given so that one understands the characters and their relationships.

Sarah Woolson is a wonderful character. She is independent and has a good logical mind, as well as a sense of humor. I particularly like the relationships with men that Tallman has created as they are natural and realistic.

The story is well thought out and well plotted. Because it is built layer upon layer, it did seem to slow down a bit in the middle, but that doesn’t last long. Some may feel the resolution seems convenient, but to me it seemed logical and appropriate.

While I don’t feel this is the strongest book in the series, I did enjoy it and am looking forward to the next book.

Rating: Good Plus.

The Sarah Woolson mystery series —

1. Murder on Nob Hill (2004)

2. The Russian Hill Murders (2005)

3. The Cliff House Strangler (2007)

4. Scandal on Rincon Hill (2010)

Thu 22 Jul 2010

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“Homicide: DR-22.” An episode of Dragnet 1969. First air date: 9 January 1969. (Season 3, Episode 14 of the color era Dragnet series.) Jack Webb (Sergeant Joe Friday), Harry Morgan (Officer Bill Gannon), Burt Mustin (Calvin Lampe), Art Balinger (Captain Hugh Brown), Len Wayland (Officer Dave Dorman), Jill Banner (Eve Wesson), Alfred Shelly (Jack Swan). Writer: James Doherty. Creator, producer, director: Jack Webb.

Joe Friday and Bill Gannon are working Homicide when they’re called in to investigate the murder of a young woman, found hog-tied on her belly in her apartment. Almost immediately, the building manager, Calvin Lampe, appears at the door and starts to point out things about the crime scene that are so obscure Friday and Gannon’s suspicions are aroused.

Later, while being informally questioned, Lampe indicates so many more unusual things about the crime — not to mention the discovery of his incriminating handprint on the wall of the victim’s apartment — that Friday decides to take him down to the station; for the moment, Lampe isn’t just the prime suspect — he’s the only suspect. But Friday and Gannon are in for a surprise when they find out who their suspect really is.

Burt Mustin (1884-1977) was all over television in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, nearly always in comic roles. In this Dragnet episode, however, he impresses in a semi-serious part. Mustin’s first film was Detective Story (1951), when he was 67 years old.

Many viewers remember him from his 14 appearances on The Andy Griffith Show (1960-66). He also showed up in “Nothing Ever Happens in Linvale,” reviewed here.

You can watch “Homicide: DR-22” on Hulu.

Thu 22 Jul 2010

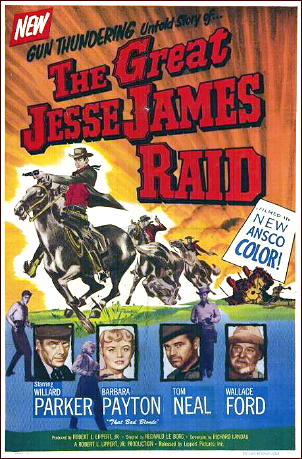

THE GREAT JESSE JAMES RAID. Lippert Pictures, 1953. Willard Parker, Barbara Payton, Tom Neal, Wallace Ford, Jim Bannon, James Anderson, Richard Cutting, Barbara Woodell. Director: Reginald Le Borg.

This movie comes as the first of six in a DVD boxed set titled “Legendary Outlaws,†so it will be easy to find, if you don’t have it and you decide to go looking. Others in the set are: Renegade Girl, Return of Jesse James, Gunfire, Dalton Gang, and I Shot Billy the Kid.

I figure that Jesse James and Billy the Kid were the two men who appeared the most often in B-western motion pictures. I don’t know which one’s the more popular, if that’s the right word, but my money’s on Billy the Kid. (I suspect that maybe you could find out on IMDB, if you wanted to, but I … What the heck. There are 80 movies with Jesse James in them, and 86 with Billy the Kid. So I win!)

Getting back to film at hand, though, Willard Parker does not make a particularly convincing Jesse James. He’s too tall, too handsome, and too blond too, for that matter.

There’s no way around it. For someone who had the starring role in Tales of the Texas Rangers on TV for three years (1955-1958), he’s too stalwart, too strong, and simply too honest to play the role of a villain as if he meant it.

Strike one.

Another flaw in this film is that the ending is given away right at the beginning, when “cowardly†Bob Ford, played by Jim Bannon, comes calling one night at Mr. Howard’s house, where Jesse, his wife and son are living under assumed names. (See above.) One last job, is the deal, and Jesse falls for it. When he leaves, his wife begs him not to go, but of course he does.

Strike two.

Even though Willard Parker was decent enough as an actor, he never got the roles that would have made him a star. Not enough flair, not enough stage presence. When the real star of your western movie is Wallace Ford, playing a grizzled old-timer brought along for his skills with dynamite, sort of an Edgar Buchanan type but without the evil glint that sometimes appeared in the latter’s eye, why then, you know your budget for the film was far too low.

Well, I’ll go ahead and say it. Strike three.

Some pluses, though. Tom Neal (of Detour fame) is a nasty piece of work, and Barbara Payton (maybe the Lindsay Lohan of her day, if not even worse) is quite a dish. (She and Tom Neal may have been living together at the time.)

But why Kate is brought along to the gold mine Jesse’s crew is working their way into, is a good question. There is no raid, per se, by the way, but things do get complicated. Not in any way that makes a lot of sense, but then again, the film is in color, and the dancing girls are nice.

Wed 21 Jul 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

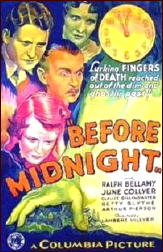

Thanks to Turner Classic Movies I recently discovered a detective film series I had never heard of before. Before Midnight (RKO, 1933) debuted on TCM in June and starred a young Ralph Bellamy as Inspector Trent of the NYPD.

A procedural this ain’t: Trent comes out on a dark and stormy night to a Toad Hall fifty miles from New York City at the request of a millionaire who expects to be killed before the ancestral clock strikes twelve. Sure enough, the murder takes place, and Trent immediately takes over the investigation, such as it is, smoking up a storm as he interrogates the dead man’s lovely ward, the doctor who loves her, the enigmatic Japanese butler, the sleazy lawyer, etc. etc.

Eventually, donning a white lab coat for forensic cred, he holds up two test tubes with blood samples in them and announces to his bug-eyed stooge that both came from the same person. How he managed to do that, generations before anyone ever heard of DNA, remains a mystery after the murder method (obvious to most viewers) and the murderer (obvious to all) are exposed.

A bit of Web surfing taught me that Before Midnight was the first of four Inspector Trent films, all starring Bellamy and dating from 1933-34. The titles of the other three are One Is Guilty, The Crime of Helen Stanley and Girl in Danger.

Columbia had released an earlier detective series with Adolphe Menjou as Anthony Abbot’s Police Commissioner Thatcher Colt but had dropped it after two films. The Trent series lasted twice as long but who today has ever heard of it? Bellamy of course went on to star in Columbia’s bottom-of-the-barrel series of Ellery Queen films (1940-41).

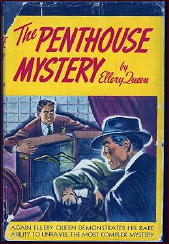

Second of the four EQ films with Bellamy in the lead was Ellery Queen’s Penthouse Mystery (1941). For most of my life I was unsure whether this picture was based on any genuine Queen material.

In Royal Bloodline I speculated that it might have come from one of the early Queen radio plays. Recently I learned that my hunch was right. Its source was the 60-minute drama “The Three Scratches†(CBS, December 13, 1939).

Someday I’d love to compare the Dannay-Lee script with the infantile novelization of the film by some anonymous hack that was published as a tie-in with the movie, but unfortunately that script was not included in The Adventure of the Murdered Moths (2005).

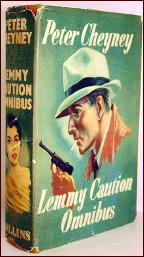

Does the name Peter Cheyney ring any bells? He was an Englishman (1896-1951), the son of a Cockney fishmonger who specialized in whelks and jellied eels.

He had never visited the U.S. but in 1936 began writing a long series of thrillers narrated in first person by hardboiled G-Man Lemmy Caution, beginning with This Man Is Dangerous (1936).

For the most part these quickies were laughed off as unpublishable over here but became huge successes in England and also in France, where translation concealed Cheyney’s habit of peppering the dialogue of American characters with British slang, not to mention self-created idioms which are like nothing in any language known to humankind.

The one that has stuck in my mind longest is “He blew the bezuzus,†which is not a musical instrument but just Cheyney’s way of saying “He spilled the beans.â€

According to Google the only known use of the word was in Sinclair Lewis’s novel Babbitt, where a character is said to have a degree from Bezuzus Mail Order University.

Could Cheyney have read that acerbic satire on the American middle class or did he come up with the word independently? Googling “bezuzus†with Cheyney’s name produces no matches, but I suspect that situation will change as soon as this column is posted.

With The Urgent Hangman (1938) Cheyney launched a series of utterly conventional ersatz-Hammett novels about London PI Slim Callaghan, and during World War II he wrote a series of rather bleak espionage novels, all with “Dark†in their titles and lavishly praised by Anthony Boucher and others.

I don’t know if he’s worth rediscovering, but you can catch him as he looked in newsreel footage from 1946, dictating his then-latest thriller to a secretary, by going to www.petercheyney.co.uk and clicking first on “Links†and then on the image at the bottom of the screen.

The mail has just brought me the proof copy of my latest assault on the forests of America. Cornucopia of Crime is a 449-page gargantua bringing together chunks of my writing over the past 40-odd years on mystery fiction and some of my favorites among its perpetrators, from Gardner and Woolrich and Queen to Cleve F. Adams and Milton Propper and William Ard, not to mention screwballs like Michael Avallone and mad geniuses like Harry Stephen Keeler.

One small problem with this copy: on the title page the author’s name is conspicuous by its absence. This glitch will soon be corrected but I’m told that ten or twelve uncorrected copies are on the way to me by mail.

If they arrive before I leave for the Pulpfest in Columbus, Ohio late next week, I plan to bring them with me and — assuming there are a few collectors in attendance who are in the market for perhaps the most limited edition of any book on mystery fiction ever published! — sell them off. Consider this an exclusive offer to Mystery*File habitues.

Editorial Comment. 07-22-10. Inspired by David Vineyard’s comments on Peter Cheyney’s contributions to the world of crime fiction, I checked out the website devoted to him that Mike mentioned. It’s definitely worth a look. I especially enjoyed the covers, a portion of one I’ve added below. Who could resist a book with a lady like this on the cover? Not me.

Artwork by John Pisani. For more, go here.

« Previous Page — Next Page »