March 2011

Monthly Archive

Tue 22 Mar 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

â— THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS. United Artists, 1936. Randolph Scott, Binnie Barnes, Henry Wilcoxon, Bruce Cabot, Heather Angel, Phillip Reed, Robert Barrat, Hugh Buckler. Based on the novel by James Fenimore Cooper. Director: George B. Seitz.

â— THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS. Associated Producers, 1920. Silent. Wallace Beery, Barbara Bedford, Albert Roscoe, Lillian Hall, Henry Woodward, James Gordon. Based on the novel by James Fenimore Cooper. Directors: Clarence Brown & Maurice Tourneur.

Since last time I’ve seen two versions of The Last of the Mohicans, neither of them the most recent one (1992).

The 1936 version starred Randolph Scott as Hawkeye and Henry Wilcoxon as Major what’s-is-name. Wilcoxon is not much remembered anymore, but in his day, he was Charlton Heston. He starred in lavish DeMille Costume Epics like Cleopatra (1934) and The Crusades (1935), and toward the end of his career played the Frisian Chieftain in The War Lord (1965).

In Mohicans he’s appropriately stuffy and heroic. As for Randolph Scott, well, he was just too young at this point to make much impression as Hawkeye, and Director George B. Seitz (best remembered for the Silent Perils of Pauline and the talky Andy Hardy series) hasn’t the virility to make him look tougher than he is, the way Henry Hathaway had a few years earlier in Paramount’s Zane Gray Series [e.g., The Last Round-Up, 1934].

Bruce Cabot is quite nice as Magua, though.

The other Mohicans was a silent version from 1920, directed by Maurice Tourneur (Jacque’s Dad) offering really fine visuals, a surprisingly gruesome massacre scene, a memorable performance from someone named Barbara Bedford as the heroine, and Wallace Beery an astonishingly sinister Magua. Without his sugary voice, Beery’s really quite convincing in this part.

Interestingly, Hawkeye is reduced to little more than a walk-on in this film, with most of the time devoted to the growing love between Cora (Bedford) and Uncas, a subplot that is sluffed over in the serial and the ’36 film.

Tue 22 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

WILLIAM L. DeANDREA – The Hog Murders. Avon, paperback original, October 1979.

DeAndrea won an Edgar for his first novel (Killed in the Ratings) despite some dissenting opinion among mystery fans. (I liked it, but George Kelley hated it.) The Hog Murders seems a likely candidate for this year’s award for best paperback.

In a snowbound city in New York State, someone who signs his letters HOG takes credit for a series of apparently unrelated deaths. When the local police are unable to make any headway, a world famous detective, Professor Niccolo Benedetti, is called in.

He and his former student, Ron Gentry, now a private detective, team up with the police to investigate. Eventually, after following a number of false leads, they discover the solution to their problem.

There are several things wrong with The Hog Murders. For one thing, the investigators overlook some indicators that are so obvious readers might feel irritation with the detectives’ stupidity. Nevertheless, I liked the book. The relationship between Benedetti and Gentry is well done (Wolfe and Archie are the obvious models), and several of the other characters are interesting (notably police inspector Fleisher).

There are also a number of fair clues to HOG’s identity scattered here and, there. If this is the first book in a series, as it seems to be, DeAndrea may very well have found himself a successful formula.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 6, Nov-Dec 1979.

Editorial Comments: As Bill predicted, The Hog Murders did indeed win an Edgar award, as the Best Paperback Original Mystery, 1980.

It took DeAndrea 13 years, however, to write two more books in the Niccolo Benedetti series: The Werewolf Murders (Doubleday, 1992) and The Manx Murders (Otto Penzler, 1994). Strangely enough neither of these two later books were reprinted in paperback.

As Bill related in this earlier post, as a judge for the first “Nero” Award, The Hog Murders was one of three books he considered as runners-up to his first choice, Lawrence Block’s The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling.

Mon 21 Mar 2011

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

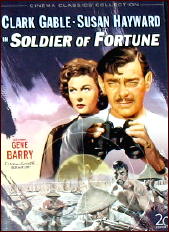

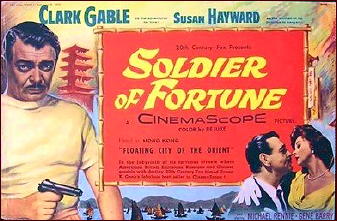

SOLDIER OF FORTUNE. 20th-Century Fox, 1955. Clark Gable, Susan Hayward, Michael Rennie, Gene Barry, Alexander D’Arcy, Tom Tully, Anna Sten, Russell Collins, Leo Gordon, Richard Loo, Jack Kruschen. Screenplay by Ernest K. Gann based on his novel. Director: Edward Dmytryk.

Jane Hoyt (Susan Hayward) comes to Hong Kong at the height of the Cold War with only one hope, an expatriate American adventurer, pirate, smuggler, and businessman, Hank Lee (Clark Gable).

Inspector Merryweather (Michael Rennie) of the Hong Kong police tries to warn her off, but she’s determined — her husband, photo journalist Louis Hoyt (Gene Barry), is being held by the Red Chinese on espionage charges, and neither the Americans or the British have any intention of rocking the boat to get him out.

Her only hope is someone like Hank Lee.

But Hank Lee sees through Jane Hoyt even as he is attracted to her. Guilt as much as love is what makes her so desperate to save her husband. Lee wants no part of her or her husband, but she’s determined and he’s attracted. (There are some obvious parallels to Hayward’s role in Henry Hathaway’s western The Garden of Evil.)

There are no surprises from this well made film and the well written novel it was based on. It’s an old fashioned adventure served up by Ernest K. Gann, a writer who knew his way around suspense, adventure, and action in best selling novels like The High and the Mighty, Island in the Sky, Fiddler’s Green (The Raging Tide), and Twilight of the Gods — all of which were successful films too.

Soldier of fortune, Lee may be, but he is also a family man with adopted Chinese children, and for all his criminal activities a man of honor. He and Merryweather have a grudging respect for each other — both men enjoy the game they are playing, though Merryweather will soon enough put him away if he catches him. Lee, for his part, is thinking of getting out of the criminal end of his enterprises before it costs him his comfortable life and family.

Jane Hoyt has shown up at just the wrong time in his life.

Or is it just the right time?

Once Jane convinces him to rescue Hoyt, Lee enlists a small army of reprobates (D’Arcy, Gordon, Collins, and Tully) and sets plans to sail to the china coast in one of his fleet of Chinese junks and land, hitting the coastal facility where Chinese general Richard Loo is holding Hoyt.

But Merryweather is closing in and Lee is falling for Jane Hoyt, and is only willing to rescue Hoyt because his shadow would be harder to fight than the man for Jane’s love.

The film was shot in technicolor and on wide screen with gorgeous Hong Kong locations and plenty of local color. Gable may have been a bit old at this point, but he could still play these roles with ease, and in this one a strong supporting cast, script, and fiery Susan Hayward as the romantic interest all contribute to the fun.

Rennie is very good as Merryweather and Barry scores well as Hoyt, a character who isn’t all that sympathetic, but who Barry at least makes believable and ultimately even a bit noble.

The finale is a well done shoot out at sea with the Red Chinese in hot pursuit of Lee’s junk.

No one wrote better about distant shores, the romance of flight, or the poetry of ships the sea, and the men who spent their lives in them than Gann, himself a pilot, sailor, and former newsreel photographer.

His novels have a poetic almost lyrical quality to them that attracted Hollywood again and again — among those filmed, the ones named above plus The Aviator, Blaze of Noon, Fate is the Hunter (non-fiction), Band of Brothers, The Antagonists (as Masada), The Adventures of Sadie, and The Last Flight of Noah’s Ark (story).

Soldier of Fortune is a slick big name Hollywood adventure film as handsome to look at and painless as the well written novel it is based on. Just how cinematic Gann’s prose was becomes obvious when you compare the two. Good book and good film, both deceptively simple and damn entertaining, with the movie made with professionals who might well have stepped out of the pages of one of Gann’s novels.

Mon 21 Mar 2011

SOPHISTICATED MURDER?

TWO NOVELS BY ANTHONY BERKELEY

by Curt J. Evans

Anthony Berkeley Cox tends to be mostly remembered for the first two of his “sophisticated,” psychological “Francis Iles” novels, Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932).

As for the more numerous crime novels Cox wrote under the name “Anthony Berkeley,” the great standouts traditionally have been The Poisoned Chocolates Case, a stunt story much praised by Julian Symons and others, and the clever criminal and judicial extravaganza Trial and Error (1937), in my opinion Cox’s magnum opus.

Little of the rest of Cox’s output gets much notice, though in my view some of it, particularly Top Storey Murder (1931), Jumping Jenny (1933) and Not to be Taken (1938), is excellent. However, there also are some extreme clunkers to be found, too!

Tellingly, when House of Stratus reprinted the Anthony Berkeley books some ten years ago, it excluded The Wychford Poisoning Case. The reason surely is the rampant sexism to be found in the tale.

Cox thought of himself as an incisive psychological novelist, but the psychological insights he offers in the Berkeley books through the utterances of his surrogate, the amateur detective Roger Sheringham, can be embarrassingly puerile, when not actually revolting.

Exhibit A in my case is The Wychford Poisoning Case, which Cox, as was his wont, rather grandiosely subtitled “An Essay in Criminology.”

The plot of the novel itself is unexceptional for Cox, following as it does a common pattern in the Berkeley tales, namely Roger Getting It All Wrong. This was the puckish Cox’s way of tweaking purist fans of the classical ratiocinative detective novel. However, after you have read a few Berkeleys you come to expect a “surprise twist” — which makes the twist, when it comes, something less than a surprise.

What is really interesting about Wychford is the utterly loopy sentiments expressed in it. Roger Sheringham’s thoughts on women in Wychford suggest that, when it comes to psychiatry, Roger would have made a better patient than practitioner.

Wychford mainly seems to be about Roger’s (and the author’s) extreme antipathy toward the modern woman of the 1920s, as embodied in the tale by the flippant flapper Sheila. ( “I’m simply revelling in all this!” she shouts at one point, “It’s fun being a detective.”

At various points Roger takes time to recommend the great need for modern women like Sheila to be spanked and to fume over these brazen females being so forward as to don male garments, pajamas. But Roger absolutely takes the cake with a jaw-droppingly misogynistic soliloquy on page 124:

“Nearly all women,,,are idiots…charming idiots, delightful idiots, adorable idiots, if you like, but always idiots, and mostly damnable idiots as well; most women are potential devils, you know. They live entirely by their emotions, both in thought and deed, they are fundamentally incapable of reason and their one idea in life is to appear attractive to men.”

Well! Now you know. Send the bill to Roger Sheringham. One has to wonder what the female writer E. M. Delafield, to whom Cox dedicated Wychford, made of all this.

This telling bit about Roger, an Oxford graduate and successful novelist (sound familiar?) appears in The Silk Stocking Murders:

Roger was a firm bachelor. He knew very little about women in general, and cared less; his heroines were the weakest part of his books.

Cox himself was married twice, though neither time successfully. He also was considered the most trying member of the Detection Club (see my forthcoming pamphlet in CADS).

In The Silk Stocking Murders (Exhibit B), the worst victims of Roger’s lamentable psychology are Jews, notoriously subjects of scorn in between-the-wars English writing (and hardly just in detective novels).

This tale promises interest as a crime story, with its four strangling murders (of women), but its narrative is plodding compared to that of the somewhat similar The ABC Murders (by Agatha Christie) and its resolution is just plain silly, in my estimation.

One of the lead characters in the tale is a Jewish financier named Pleydell. Cox actually takes pains to make clear that Pleydell is not one of those objectionable Jewish financiers, don’t you know — though his explanation is itself problematically patronizing:

“Now that Roger could observe [Pleydell] more nearly than in the court, he saw that the Jewish blood in him was not just a strain, but filled his veins. Pleydell was evidently a pure Jew, tall, handsome and dignified as the Jews of unmixed race often are.”

The most cringeworthy moment in Silk Stocking comes when Roger and the pointedly named Anne Manners — the sympathetic (non-modern) female character in the tale — further anatomize Pleydell over tea:

“I’ve never met a Jew I liked so much before,” Anne remarked.

“The real pure-blooded Jew, like Pleydell,” Roger told her, “is one of the best fellows in the world. It’s the hybrid Jew, the Russian, Polish and German variety, that’s let the race down so badly.”

“And yet he seems as reserved and unimpassioned as an Englishman,” Anne mused. “I should have thought that the pure-blooded Jew would have retained his Oriental emotionalism almost unimpaired.”

Roger could have kissed her for the slightly pedantic way she spoke, which, after a surfeit of hostesses and modernly slangy young women, he found altogether charming.

Most modern readers will probably find Anne (and Roger) altogether less than charming here.

Thriller writers like “Sapper” often get smartly rapped over the knuckles by indignant critics for obnoxious anti-Semitic elements in their writing, but with more “sophisticated” writers like Cox this sort of thing tends to get overlooked.

The teatime duologue between Anne and Roger that Cox subjects us to in Silk Stocking is a reminder than the anti-Semitism that plagued Europe in the 1920s and 1930s (with fatal results for millions in the 1940s) was hardly confined to the knuckle-dragging elements.

But just how sophisticated was Cox, really?

I get the feeling that Cox at some level recognized flaws within himself and thus made his ego projection, Roger Sheringham, frequently fall on his face in the Berkeley tales. Yet I sensed no indication in Wychford and Silk Stocking that Cox was satirizing (or disagreeing with) Roger’s views on women and Jews.

Moreover, although Roger (and Cox) love to prate about psychology, the “psychological” solution of the four murders in Silk Stocking is labored and unconvincing, an indication that, despite all the talk, Roger and his creator are mere dabblers in the psychological arts, often shamelessly winging it when it comes to expository solutions of crimes, even when Roger actually is meant by the author to be Getting It All Right.

SPOILER

The murderer in Silk Stocking turns out to be the seemingly sympathetic Jew, Pleydell. We are told by Roger that Pleydell was mad and that the first two in his series of four murders were “pure lust-murders” but that the third was a “vengeance-murder, or a megalomania-murder, if you like” and the fourth was a “murder committed with the sole motive of increasing the strength of the case against the man he loathed.”

With this surfeit of muddled motivations on the part of one mad murderer, the brilliant clarity of Agatha Christie’s solution to a series of killings in The ABC Murders is utterly lacking in The Silk Stocking Murders.

END SPOILER

I have the uneasy feeling that in his cases — even the ones he is actually meant to solve — Roger is just talking out of his hat. Call me unsophisticated, if you like.

Mon 21 Mar 2011

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

CHARLES TODD – An Impartial Witness. William Morrow, hardcover, August 2010. Trade paperback: Harper, August 2011.

Genre: Amateur sleuth. Leading character: Bess Crawford; 2nd in series. Setting: England-France, 1917-World War I.

First Sentence: As my train pulled into London, I looked out at the early summer rain and was glad to see the dreary day had followed me from Hampshire.

WWI battlefield nurse Bess Crawford had been caring for a badly burned young pilot who had a picture of his wife visibly displayed. In a train station traveling on leave back to London, Bess happens to see the wife who is clearly upset as she sees off a different soldier.

Although somewhat perplexed by the scene, it is nothing to the shock Bess feels when a drawing of the woman appears in the next day’s paper with Scotland Yard asking whether someone can identify her. Bess learns the woman had been murdered and shortly after, the burned husband commits suicide. Bess feels it is her responsibility to find out what had happened.

This is the second book in this new series by the Todds and I much preferred it to the first book. Their voice for Bess is much better and she’s a stronger character.

The sense of chaos and fatigue from being in combat is well conveyed, but with a sense of detachment I feel one would acquire after time. The contrast between the battlefield and being in London, particularly attending the house party, is very effective.

I like that Bess doesn’t jump to conclusions but gathers the evidence bit-by-bit and over time. The plot was well constructed and the reason for Bess being involved was justifiable. Although I understood Beth’s distance from the events, it did all feel a bit too distant as a reader; I was never emotionally connected to the story.

While I never considered not finishing the book, for me it wasn’t a gripping straight-through read either. That said, Todd is an excellent writer and I always look forward to the next book.

Rating: Good Plus.

The Bess Crawford mysteries —

1. A Duty to the Dead (2009)

2. An Impartial Witness (2010)

3. A Bitter Truth (2011)

Mon 21 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Awards[11] Comments

HERE COMES THE JUDGE: THE “NERO” AWARD, 1979

by Bill Crider

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 6, Nov-Dec 1979.

The first annual “Nero” award, named for Nero Wolfe and given in honor of his creator, Rex Stout, was won by Lawrence Block for The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling. The award, a replica of Wolfe’s famous gold bookmark, was presented at a Black Orchids Dinner, December 1, 1979, in New York City. The winner was chosen by a panel of judges named by the Stout fan club known as The Wolfe Pack.

This award was of special interest to me because I was one of the judges. I have no real idea why I was selected to serve, as I am not a member of the Wolfe Pack and I am hardly so deluded as to think that my reputation for criminous knowledge has spread even unto the Wolfe Pack hierarchy. But I have been corresponding with John McAleer, Stout’s biographer, for a number of years, and I even helped him a tiny bit in his researches. Maybe he wanted to do me a favor.

At any rate, I was told that I should try to judge the books I received by how well they carried on the tradition of Rex Stout. I took that to mean that I should look for a book that had some of the qualities of Stout’s work, rather than one that simply imitated the master. The catch was that publishers were asked to nominate books, and the judges could make their selections only from those books which the publishers nominated.

In a way, this made my job easier. Many publishers obviously had no idea about the tradition of Rex Stout, and I had to read only a few pages of the books to see that they wouldn’t do at all. Some of them I finished; others, I didn’t.

For example, Doubleday submitted, among others, Domino, by Phyllis A. Whitney. Now, some of my best friends like Phyllis A. Whitney, but a gothic set in Colorado is not my idea of a book which is in any way like anything Rex Stout wrote.

Lippincott sent The Green Ripper, which was not bad MacDonald but which wasn’t really even a mystery. (One of my criteria was that the book had to be a mystery, which eliminated not only MacDonald but such spy stories as Victor Canning’s Birdcage and Campbell Black’s Brainfire.)

Some of the actual mysteries eliminated themselves, like Stephen Greenleaf’s Grave Error, which was too slow and too much like Ross Macdonald. Then there was The Reggis Arms Caper by Ross Spencer, not a bad joke, but the joke’s getting a little thin.

What it boiled down to was that as far as I was concerned, there were only four real contenders in the group of books that I had to select from. I thought that since there were a number of other judges, there might have to a compromise. There might have been on the part of others, but my first choice was the winner, Block’s Burglar. Only the top prize was awarded, so my other choices weren’t really necessary.

I voted for Block’s book because I like the way he handles first person narration; while Bernie the burglar is no Archie, he’s pretty good. Besides, the book is a real mystery, in which the suspects are called together at the end. And the relationships among the characters are well done.

My second choice, I have to admit, was more obviously based on the Wolfe books. It was William DeAndrea’s The Hog Murders, an Avon paperback original. As DeAndrea is a member of The Wolfe Pack, it’s just as well he didn’t win; as some might have thought that the judging was rigged.

Other books that I considered in the running were Simon Brett’s A Comedian Dies and Marvin Kaye’s My Brother, the Druggist. These latter three, however, were my personal choices; I don’t know how the other judges felt about them.

Judging the award was an interesting experience, and I got a huge stack of free books for my shelves. Apparently the Wolfe Pack was satisfied with the work of all the judges and may be using the same panel again for the 1980 award. That will be fine with me. I just can’t turn down a free copy of a good mystery. Or even a bad one.

The one thing I learned from my experience is that there is no one to replace Rex Stout. Nero and Archie are unique. We’ll never see their like again.

Coming soon to this blog:

Bill reviews The Hog Murders and My Brother, the Druggist.

THE NERO AWARD WINNERS:

* 1979 – The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling by Lawrence Block

* 1980 – Burn This by Helen McCloy

* 1981 – Death in a Tenured Position by Amanda Cross

* 1982 – Past, Present and Murder by Hugh Pentecost

* 1983 – The Anodyne Necklace by Martha Grimes

* 1984 – Emily Dickinson is Dead by Jane Langton

* 1985 – Sleeping Dog by Dick Lochte

* 1986 – Murder in E Minor by Robert Goldsborough

* 1987 – The Corpse in Oozak’s Pond by Charlotte MacLeod

* 1988 – no award presented

* 1989 – no award presented

* 1990 – no award presented

* 1991 – Coyote Waits by Tony Hillerman

* 1992 – A Scandal in Belgravia by Robert Barnard

* 1993 – Booked To Die by John Dunning

* 1994 – Old Scores by Aaron Elkins

* 1995 – She Walks These Hills by Sharyn McCrumb

* 1996 – A Monstrous Regiment of Women by Laurie R. King

* 1997 – The Poet by Michael Connelly

* 1998 – Sacred by Dennis Lehane

* 1999 – The Bone Collector by Jeffery Deaver

* 2000 – Coyote Revenge by Fred Harris

* 2001 – Sugar House by Laura Lippman

* 2002 – The Deadhouse by Linda Fairstein

* 2003 – Winter and Night by S.J. Rozan

* 2004 – Fear Itself by Walter Mosley

* 2005 – The Enemy by Lee Child

* 2006 – Vanish by Tess Gerritsen

* 2007 – All Mortal Flesh by Julia Spencer-Fleming

* 2008 – Anatomy of Fear by Jonathan Santlofer

* 2009 – The Tenth Case by Joseph Teller

* 2010 – Faces of the Gone by Brad Parks

Sun 20 Mar 2011

THE CRIMSON CANARY. Universal Pictures, 1945. Noah Beery Jr., Lois Collier, John Litel, Steven Geray, Claudia Drake, Danny Morton, Jimmie Dodd, Steve Brodie, John Kellogg, Arthur Space. Josh White, the Esquire All-American Band Winners with Coleman Hawkins, Oscar Pettiford. Director: John Hoffman.

Even though I love old B-movies, especially old B-for-budget detective films, I have to admit that most of the time I’m disappointed. Noir films made for the same amount of money got by on atmosphere. Detective films of the 1930s and 40s of the punch-them-out variety may have had atmosphere, but most of them don’t hold up as detective fiction.

The Crimson Canary is one that does, more or less, making it one of the “good†ones. Not one up to the standards of a Agatha Christie or a John Dickson Carr, but in comparison to its competitors, Canary stands out like an upraised thumb.

But atmosphere? That it’s got, and more. Noah Berry Jr. heads up a group of wartime buddies in a jazz band, and boy do they swing. Strictly small time stuff, stuck in a small town nightspot, but good enough to have hopes – and to have a good looking vocalist flirt with all the guys, and with Danny Brooks (Beery) with a steady girl friend yet.

When the girl’s found dead in a back room, the guys take it on the lam – joining up when the coast is clear, they think – but it’s not, not with a jazz-loving police detective (John Litel) breathing down their necks and watching every move they make.

The music is great, and the detective end of things (as I said up front) good. The only flaw is that there’s only a very limited number of suspects. In 64 minutes, with 20 of them taken up by musical numbers (my very rough estimate) there simply isn’t time enough to introduce anyone else who could have done it.

Highly recommended for fans of jumping and jiving 1940s pre-bop jazz.

Note: From the AFI page: “…the musicians who dubbed the quintette were Nick Cochrane and Eddie Parkers, trumpet; Stan Wrightsman, piano; Barney Bigard, clarinet; King Guion, tenor sax, and Mel Tormé, drums. Coleman Hawkins was supported by Howard McGhee, trumpet; Sir Charles Thompson, piano; Denzil Best, drums; and Oscar Pettiford, bass.†Check out this two minute clip from YouTube.

Sun 20 Mar 2011

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

R. A. J. WALLING – Marooned with Murder. Morrow, hardcover, 1937. UK edition published as Bury Him Deeper, Hodder & Stoughton, hc, 1937.

R. A. J. Walling, a British journalist and newspaper editor who began writing mysteries as a hobby in his late fifties, received a good deal of acclaim during his time. (His first book was published in 1927, his last posthumously in 1949.)

The New York Times stated in 1936 that Walling had considerable skill in weaving mystery plots; the Saturday Review of Literature decided that he wrote suavely baffling stories; the eminent critic Will Cuppy said of one of his early novels that it was “absolutely required reading.”

This reviewer couldn’t agree less.

In the first place, Walling wrote some of the dullest mysteries ever committed to paper; it may even be said that he elevated dullness to a fine art. And in the second place, his series sleuth, private inquiry agent Philip Tolefree, is a twit.

He says things like, “You’re a vandal, Pierce. You’ve feloniously broken into my ivory tower. Never mind. I’d have been bored in another half hour. How’d you find me out? Sit down, my dear fellow. Cigarette? Pipe? Well, carry on. What’s the trouble now? Or did you come for the sake of my beautiful eyes?”

He is also fond of quoting obscure Latin phrases, treating his sometime Watson, Farrar, as if he were an idiot, and withholding information from everyone including the reader.

Although Tolefree operates out of a London apartment, most of his cases seem to take him into the countryside. He solves them in the accepted Sherlockian manner of detection and deduction, using an inexhaustible fund of knowledge both esoteric and ephemeral.

Another reason he is so successful at unmasking murderers is his familiarity with such matters and motives as skeletons in closets, hidden relationships, peculiar wills, strange disappearances, and Nazi infiltrators, since nearly all his investigations seem to uncover one or any combination of these.

Marooned with Murder is no exception; its central plot points are hidden relationships and a strange disappearance. It begins well enough, with a dandy premise: Tolefree and Farrar, on a holiday in the Scottish Highlands, decide to rent a boat and sail her out of one of the fjordlike lochs into the Atlantic.

A sudden storm shipwrecks them on the tiny island of Eilean Rona, where they are rescued by the lord of the isle, Martin Gregg; artist Bill Parracombe; and two odd and fiercely loyal Scotsmen, Fergus and Jamie. Also staying at the island’s ancient castle for the summer are Gregg’s wife and small son, and the boy’s governess.

The storm continues to batter Rona, preventing any of them from leaving. A chance remark by Farrar, about a retired sea captain he knows named Strachan who lives over on the mainland, for some reason seems to frighten everyone; so does the remark that Tolefree is a detective.

It soon becomes clear that Strachan had been hunting lost treasure on the island and disappeared one foggy Sunday three months before, along with his boat and a mysterious companion; and that the inhabitants of Rona know something about that disappearance and are desperate to protect their guilty knowledge.

So far, so good. But Walling spoils the stew by interminable passages of cat-and-mouse dialogue, annoying cryptic remarks from Tolefree, and a lot of rather silly running around. He also lets the reader know early on that Tolefree and Farrar do not fear for their lives; they think their hosts are all swell people, even though one of them may be a murderer.

The result is plenty of mystery but no menace and therefore no tension. And the mystery isn’t satisfying, either, when its rather predictable solution is revealed.

Walling has been called (by his publishers) “the foremost exponent of the seemingly ‘quiet’ mystery, the civilized story with … excitement and drama seething below the surface.”

Readers who don’t find that a euphemism for dull, and would like to examine Walling’s work for themselves, should try The Corpse in the Coppice (1935), The Corpse with the Floating Foot (1936), The Corpse with the Eerie Eye (1942), and A Corpse by Any Other Name (1943). The last-named title has some effective descriptions of Londoners coping with the wartime blackout and blitz.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 20 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

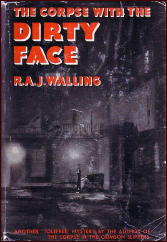

R. A. J. WALLING – The Corpse with the Dirty Face. Morrow, hardcover, 1936. UK edition; Hodder & Stoughton, hc, 1936.

Upon first inspection the black markings smeared across the victim’s face appear to be huge inkstains sustained during the act of murder. Later it’s learned that they were permanently disfiguring powder burns the dead man received during the war — World War I, that would have been.

They’re still important enough as a factor in solving the murder to give the case its title, and a good deal of diligent detective work is needed to unravel the maze of conflicting alibis that bars the way. Also needed is an explanation for the several uncharacteristic changes of plan the victim made for the evening during the crucial time just before his death.

On the scene from very nearly the beginning is Mr. Tolefree, a private detective of the “softboiled” English butler variety. The only character to display real signs of life is the dead man’s daughter, determined not to let her loved one be accused of the crime.

It takes a strenuous grip on a great number of assorted facts to solve the puzzle before Mr. Tolefree does, and even so I question the fairness of one of the essential clues. Making up for it is a solidly constructed piece of misdirection at one point, and equally pleasing was a bit of unexpected subtlety in the prologue. Even with the portentous warning Walling gives the reader in the very first paragraph, it goes unnoticed very easily. On the whole, nicely done.

A good movie it wouldn’t make, however. Too many shots of heads, doing nothing but talking.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 6, Nov-Dec 1979.

[UPDATE] 03-20-11. This, of course, is the review I promised as a follow-up to Geoff Bradley’s review of an earlier Walling mystery, which produced a lot of comments, mostly neutral (ho-hum) to negative. This one I liked, though, in spite of all the flaws I found and pointed out. Whether I’d feel the same way, today, I cannot tell you, nor have I read another by Walling since.

Coming up next: Bill Pronzini’s 1001 Midnights review of the same author’s Marooned with Murder. Be warned. He did not like it, and he is willing to tell you why.

Sun 20 Mar 2011

“MURDERS OF THE MONTH”

October 24, 1932

Herewith the detective fiction books of the previous month, as selected by Time Magazine, October 24, 1932. They are listed in order of merit, as stated in the article, along with brief descriptions of the plots of each. How many have you read?

THE STUDENT FRATERNITY MURDER—Milton Prosper —Bobbs-Merrill ($2). Skilled Detective Rankin points the crime through yellow hoods and yellow hair.

THE END OF MR. GARMENT—Vincent Starrett—Crime Club ($2). Stabbing of a famed writer whom many disliked and had opportunity to kill.

THE CORPSE ON THE WHITE HOUSE LAWN—“Diplomat”—Covici, Friede ($2). A smart, lucky young diplomat solves the code, retrieves the papers, catches the murderer.

THE RESURRECTION MURDER CASE— Stanley Hart Page—Knopf ($2). Christopher Hand forces self-identification of the murderer by trickery with a skull.

POISON IN JEST—John Dickinson Carr — Harper ($2). Introducing mirth-provoking Detective Rossiter in poison cut. hatchet murder and necrophilia. [sic]

MURDER IN MARYLAND—Leslie Ford—Farrar & Rinehart ($2 ). The murder of a small town’s most hated woman solved by the town’s woman doctor.

DOUBLE DEATH—Freeman Wills Croft —Harper ($2). Sly tricks in murder on a background of railroad construction.

INSPECTOR HIGGINS HURRIES— Cecil Freeman Gregg—Dial ($2). Twenty-four hours of hurly-burly mystery-solving.

CUT THROAT — Christopher Bush — Morrow ($2). Much ado about clocks.

MURDERER’S LUCK — Henry Holt — Crime Club ($2). Multiple killings in rural England.

THE SECRET OF THE MORGUE—Frederick G. Eberhard — Macaulay ($2). Autopsy technique in a story of bootlegging and body-swapping.

THE OSTREKOFF JEWEL— E. Phillips Oppenheim—Little, Brown ($2). A young diplomat gets a princess and her jewels out of revolutionary Russia, with, of course, difficulties.

MURDER ON THE GLASS FLOOR—Viola Brothers Shore— Long & Smith ($2). A liner’s new dance floor christened by a murdered woman.

« Previous Page — Next Page »