June 2014

Monthly Archive

Wed 18 Jun 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

C. A. ALINGTON – Gold and Gaiters. Faber and Faber, UK, hardcover, 1950. No US edition.

In Chapter Five, on page 65, the Reverend Cyril Alington says readers may complain that a novel without “a hero is one thing, but a novel without action quite another.” Action remains lacking for a goodly number of pages — until Chapter Nine, Page 97, in fact — but the appreciative reader won’t care.

This novel should be read, as are the “crime” novels of P. G. Wodehouse, for the author’s style and humor. By the time the gold Roman coins are stolen from the Cathedral Library, which is in the charge of Archdeacon Castleton, that good man, the reader should be enjoying himself or herself far too much to worry about what is happening or not happening.

Delightful froth.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Bio-Bibliographic Note: According to Wikipedia, “Cyril Argentine Alington (22 October 1872 – 16 May 1955) was an English educationalist, scholar, cleric, and prolific author. He was the headmaster of both Shrewsbury School and Eton College. He also served as chaplain to King George V and as Dean of Durham.”

The Wiki page also contains an extensive bibliography. Of those a dozen are detective fiction, and of course they can also be found in Hubin, including one as by S. C. Westerham. If you’re interested, two copies of Gold and Gaiters are available on the Internet at the current time, both in the $20-30 range.

Wed 18 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

FRED VARGAS – The Ghost Riders of Ordebec. Penguin, US edition, softcover, June 2013. Police procedural: Commissioner Adamsberg; 7th in series. Setting: France.

First Sentence: A trail of tiny breadcrumbs led from the kitchen into the bedroom, as far as the spotless sheets where the old woman lay dead, her mouth open.

Comm. Adamsburg travels to Ordebec in response to a woman’s plea. Her daughter, Lina, has seen the Ghost Riders with four men. According to legend, this mean each of these men will meet a violent death. Adamsburg takes with him a young man he believes innocent of the murder for which he is accused, and his 18-year-old son, whom he recently met. Although entranced by the lovely Lina, one of the envisioned men does die and it’s time for Adamsburg to get to work.

There is nothing ordinary about a Fred Vargas book. It begins with a unique murder, quickly solved by Adamsberg, which quickly displays his understanding of people and their behaviors.

The Serious Crime Unit, of which he is the head, is a collection of strange and unusual individuals. It’s hard to imagine how they solve crimes, but solve them they do. Vargas even keeps the characters from her book “The Three Evangelists†included in this series.

Legends, ghost stories, witchcraft, and the supernatural are included in the story, but don’t overtake the fact that this is, at its core, a police procedural. Yet her books are definitely character-driven focusing not only on their physical presence, but their personal characteristics.

There is something mercurial and wise about Vega’s writing that can make you stop and think…â€The world’s full of details, have you noticed? And since no details is ever repeated in exactly the same shape and always sets off others details, there’s no end to it.â€

The Ghost Riders of Ordebec started off just a bit slowly but quickly made up for it. It is, as are all her books, wonderfully weird and very French. You’ll either be completely entranced by Vargas’s writing, or she’ll just not quite be your cup of tea. Me? I’m firmly in the former group.

Rating: VG Plus.

Editorial Note: LJ previously reviewed the fifth book in this series, Wash This Blood Clean from My Hand, here on this blog some time ago. You can read her comments by going here. That previous post also includes a bibliography through book six in the series.

Tue 17 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN. Universal Pictures, 1943. Ilona Massey, Patric Knowles, Lionel Atwill, Bela Lugosi, Maria Ouspenskaya, Dennis Hoey, Lon Chaney Jr. Screenplay: Curt Siodmak. Director: Roy William Neill.

Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man is a horror film starring Lon Chaney Jr. In this quixotic production, Chaney reprises his role as Larry Talbot/The Wolf Man, the eponymous character of Curt Siodmak’s 1941 horror classic about a man who, against his own volition, turns into a werewolf during the full moon.

Along for the ride through this fairy tale land are Iloney Massey as Baroness Elsa Frankenstein, Patric Knowles as Dr. Frank Mannering, Talbot’s physician, and Bela Lugosi as a rather underwhelming Frankenstein Monster. Saving the film from its preposterous premise, encapsulated so clearly in the film’s title, is the skillful direction of Roy William Neill. (I reviewed Neill’s Gothic masterpiece, The Black Room starring Boris Karloff, here).

The plot is basic enough. Grave robbers come across the Talbot tomb in a very eerie looking cemetery somewhat reminiscent of the one seen in the beginning of Lew Landers’s The Return of the Vampire (reviewed here). Their attempt to rob the family tomb is thwarted by Larry Talbot/The Wolf Man who turns out not to be so dead after all.

Ever since he was initially bitten by a werewolf and transformed into one himself, Larry simply cannot die. He kills at night during the full moon and he hates himself for it. He simply wants to die. Indeed, that’s what takes up the majority of the film’s time — seeing a somewhat pathetic and moping Chaney/Talbot wonder around from place to place trying to find someone who will help him end his cursed existence. One person he seeks out is the elderly, mysterious Gypsy woman, Maleva, portrayed by the Russian actress, Maria Ouspenskaya, who had the same role in Siodmak’s The Wolf Man.

Talbot and Maleva make their way through central Europe where Talbot encounters Baroness Frankenstein (Massey) and urges her to turn over her father’s records. He wants to learn how her father’s experiments might help him die. Talbot also inadvertently discovers an iced over Frankenstein Monster (Lugosi) and releases him from his frozen tomb. One really has to suspend disbelief to make it through this part of the film.

Soon, Dr. Mannering (Knowles), who was Talbot’s physician earlier in the movie, shows up and decides that he’s going to become a mad doctor. He ends up both strengthening the Frankenstein Monster and, with the assistance of a full moon, turning Talbot into a werewolf on the same night.

Finally, the Frankenstein Monster and the Wolf Man go at it, fighting as monsters do. It’s actually a fun little sequence with memorable camera angles and a visually stunning Gothic laboratory setting. But the monster versus monster fight doesn’t last long. One of the townspeople, against the advice of the mayor (Lionel Atwill), decides he’s going to sabotage the Frankenstein Castle and kill the monsters.

When the movie ends — too abruptly, it should be noted — it would seem as if both the Frankenstein Monster and the Wolf Man have been laid to rest. (The 1944 sequel, House of Frankenstein, reviewed here by Dan Stumpf and by Walter Albert here, will demonstrate that this was not the case).

While Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man isn’t a particularly good horror film, it’s actually a fairly decent monster movie. True: Chaney’s character really doesn’t do much but whine and beg people to help him die. And Lugosi is not Karloff. But Roy William Neill’s direction makes the film an enjoyable, if admittedly mindless, viewing experience. Quirky camera angles, great settings, and skillful uses of shadow and lighting make this transparent effort by the studio to capitalize on the successes of both Frankenstein (1931) and The Wolf Man significantly better than it could have been in a far less capable director’s hands.

Mon 16 Jun 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

KEOMA. 1976. Also released as Django Rides Again and The Violent Breed. Franco Nero, Woody Strode, Olga Karlatos, Donald O’Brien, William Berger, Gabriella Giacobbe. Directed by Enzo G. Castallari.

An arty and allegorical Spaghetti Western with half a brain and good direction and cinematography, Keoma turns out to ultimately be more entertaining than annoying, and better acted than it has any right to be with an existentialist message at the end right out of Sartre.

Keoma: “He won’t die, he’s free. And a free man can never die.â€

Okay, if he says so, but for all that, this proves to be a really good western of its type, with first class performances by Franco Nero and Woody Strode, and one stunningly beautiful pregnant woman (Olga Karlatos) named Lisa who bears the burden of most of the allegory about life, death, birth, existence, sacrifice, suffering, freedom, and hope (well, she is very pregnant).

Admittedly that’s a lot for a western– even an Italian-made western shot in Spain — to bear, but this one manages better than most. It makes for some pretentious fun. It’s no where near as good as High Plains Drifter, but it’s nowhere near as bad as Pale Rider, as pretentious westerns go.

Nero is the gray eyed long-haired (how those braids survive holding the mess back got a bit distracting I have to grant) half-breed Keoma, who returns home after the Civil War.

“Which side were you on?â€

“It just happened I was on the winning side.â€

There he finds a spooky old Indian witch (Gabriella Giacobbe) who wanders in and out of the film like a silent Greek chorus as Keoma’s conscience and a sort of early warning signal of impending trouble. She warns him he should not have returned, but like any western hero in any western ever made anywhere, common sense isn’t his long suit, so he rides right into a group of ex-Confederate cackling coyote-mean escapees from Deliverance (are there any other kind?), taking prisoners with the plague to the mines to isolation and death.

Among them is one pregnant woman, Lisa, the stunningly beautiful Karlatos, with eyes every bit as spooky as the wolf eyed Nero. Pregnant, with straggly hair, and in extremely unflattering clothes, she is still one of the most beautiful women you will ever see in any film.

Typically he makes enemies fast, kills one of the ex-Rebs, and takes the woman to town, where no one wants her, and he promptly has to kill again and further annoy an ex-Confederate rancher and power mad criminal named Caldwell (Donald O’Brien, the film’s weakest link) who caused the plague with poisoned wells, and now holds the town hostage refusing to allow anyone to bring in medicine or help. No one ever explains just how this helps him since he has already grabbed all the land. I guess he’s just mean.

In addition Keoma finds his childhood friend and mentor George (Woody Strode) a broken old drunk waiting to die in the streets.

Keoma: “But you’re free now.â€

George: “I found out what freedom means.â€

Like heavy, man (well, it was the seventies).

Keoma it turns out was a half-breed child rescued by a fast gun, William Shannon (William Berger), with three sons of his own. Of course they are no damn good — they tortured and beat Keoma — and as ex-Confederates themselves, they ride with Caldwell and their once proud and deadly father is old, afraid to die, and fears having to kill his own sons. But he’s glad to have Keoma back.

Shannon: “We stopped slaughtering and butchering the Indians long enough to free the black man and now we are back to finish with the Indians.â€

That comes a bit out of left field, since other than the knowledge that Keoma’s village was slaughtered by white men and Keoma the only survivor, and all the bad guys, brothers included, go on about him being half-Indian, Indians have almost nothing to do with the plot except as shorthand for oppressed and exploited people, and that old Indian woman (great face) who keeps wandering in and out at key points often back lit by lightning and sunlight.

This is a beautifully shot film. Visually it is great to look at and the print I saw was off an original 35mm letterboxed master in one of those collections of twelve films, this one including One Eyed Jacks, another pretentious western, but not as good as this one despite the cast and stunning cinematography.

Keoma is about as much Tarzan or Conan here as a western hero, a sort of force of nature, the ultimate existentialist hero who worships only one thing, freedom at any price — no matter who he gets killed in winning it for them.

It’s a very physical role for Nero, mindful of the kind of action film Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas often made full of running, leaping, fighting, and defying gravity, and in the stunts that are obviously Nero, he looks and performs the physical side more than adequately. Of course he was an old hand at this and even makes a sly cameo in Quentin Tarantino’s paean to the form, Django Unleashed (for anyone who didn’t get the joke Nero — among others — this was also released as Django Rides).

You have to give the director and multiple screenwriters credit too, because this could easily have devolved into maudlin flashbacks of Keoma’s troubled childhood, but instead they chose a form of virtual Latin American Magic Realism where the characters in the here and now are physically in the flashback scenes with their younger selves. Once you get past the initial shock it is very effective and in some ways presages the famous ending of Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart.

You can guess how the plot works out: there’s the good doctor who regains his nerve; George regains his manhood; Shannon stands by his good adopted son, Keoma; Shannon and George take on the entire Caldwell army in a well shot orgy of gunfighting and violence; and Keoma ends up crucified in the rain on a wagon wheel in the middle of town only to be rescued by Lisa, the dying pregnant woman.

The final shootout in an old abandoned fort where the film opened, with Keoma battling his three adopted brothers is well staged with the screams of the woman in labor and the cries of her newborn muffling the gun fire (I warned you it was arty) and the old witch looking on.

But don’t shoot me, it isn’t my fault that Keoma, having done everything but backflips to see the child is born, then deserts him with the old Indian woman with than nonsense about a free man can’t die. See how much milk and how many diapers existentialist philosophy will buy you; carrying existentialism a shade too far as far as I’m concerned.

The major problem for me was the damn musical soundtrack, really lame senseless ballads I could barely understand that sounded like the mewling of the cattle from Red River done to music or the male part like a coyote with a sore throat trying to spit phlegm up (and that is being kind — “Do not forsake me oh my darlin'” it’s not), the woman singing alone had a vibrato on high notes that must be how Madame Castafiore sounds to Captain Haddock in Tintin. You will be amazed how many vowels she manages to squeeze into the name Keoma. She sounds like the love child of Joan Baez and Slim Whitman.

That said, the dubbing was first class with Nero and Strode at least doing their own voices.

But messy as it is at times, I more than recommend this one. It mostly succeeds at what it is obviously trying to do, there is some strong and effective imagery, plus stunts, good use of lighting and staging, and more often than not, it rises to what it seems to want to be. Granted the main villain is a bit lame, but he’s only an afterthought to the conflict between the brothers and Keoma.

And if any of you have seen it and remember, maybe you can clear up whether Keoma was just rescued by Shannon, or Shannon’s son by his Indian mother. At one point that seems to be the implication, and then later I wasn’t so sure. I guess that happens when a small army writes the screenplay. They never clear up if the people at the mine dying of plague are saved either. Guess it wasn’t worth the bother.

I enjoyed this one much more than I expected. If there is another half this good on the set then I won’t feel I wasted $5. This is one of the better thought of and appreciated later Spaghetti westerns, and it isn’t hard to see why.

Still, I can’t help but wonder if Tonto — Keoma — would have fared better here with the help of the Lone Ranger.

Just asking.

Mon 16 Jun 2014

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

JOHN WALTER PUTRE – Death Among the Angels. Scribner, hardcover, February 1991. No paperback edition.

John Walter Putre brings back his private eye Doll in Death Among the Angels, a book with little to recommend: no people I’d care to meet again, a rather insubstantial plot insubstantially resolved, an unmemorable Florida setting, muddy motivations.

An old girlfriend of Doll’s asks his help: she’s in jail, charged with the murder of her current boyfriend. She refuses to talk to her lawyer, says she was drunk during the critical night and doesn’t remember what happened, and in dare course also refuses to talk to Doll.

What’s behind all this? Well, maybe an illegal salvage operation, into which — as is usual in these matters — it may be fatal for Doll to inquire.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Bibliographic Note: This is the second of only two works of detective fiction involving Doll, the first being A Small and Incidental Murder (Scribner, 1990).

Sun 15 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

“A DEATH OF PRINCES.” An episode of Naked City, ABC, 12 October 1960 (Season 2, Episode 1). Paul Burke, Horace McMahon, Nancy Malone, with Eli Wallach, George Maharis, Jan Miner. Teleplay: Stirling Silliphant. Directed by John Brahm.

“A Death of Princes” is the second season opener of Naked City, the ABC police procedural starring Paul Burke as Detective Adam Flint and Horace McMahon as his crusty but amicable boss, Lt. Mike Parker. Guest starring is Eli Wallach portraying Detective Bane, a cynical rogue cop involved in blackmail, robbery, and murder.

In this taut, action-packed episode, Wallach’s Brooklyn-accented character is quite similar to the sociopathic hit man, Dancer (portrayed by Wallach in a great film noir role), in Don Siegel’s The Lineup, which I reviewed here.

The episode begins with church bells and gunfire. It’s Sunday. Adam (Burke) and Bane (Wallach), partners for the time being, are chasing an armed thug through an industrial district and to the top of a building overlooking the river. The criminal doesn’t have much luck. His gun jams and he cowers helplessly on the ground. That’s when Bane plugs him.

Adam realizes what just happened and is shocked his partner just killed defenseless suspect in cold blood. Bane tells Adam he saw things wrong. But he doesn’t seem to care much anyways. Of the dead man, Bane says: “Look at him, a pile of nowhere. He came, he went, and who cares.†These criminally poetic words let us know from the get-go exactly what type of character Bane is going to be.

Back in the precinct headquarters, Adam tells Mike he wants out. He no longer wants to work with Bane. Mike originally won’t hear of it, but he gradually changes his mind, allowing Adam to trail Bane to figure out what sort of criminal activity the rogue lawman is up to.

As it turns out, Bane is blackmailing three people into working for him on a job. His objective is to steal money raised during a charity prizefight. Among the people Bane is blackmailing is the boxer, Tony Bacallas (George Maharis), who turns out to be the only redeemable criminal among the bunch.

Bane, the most corrupt of the four, hates the fact that he has to rely upon what he perceives as scum, common criminals, to achieve his goals, telling them: “I despise myself because I need you.†It’s so dark, so cynical, and so very noir.

And as in many noir stories, the criminal ends up down a path that lead to his doom. “A Death of Princes” is no exception. Adam, who was originally shocked by Bane’s capacity for violence, eventually shoots and kills Bane, leaving him dying alone on the carpet. But how can we feel sorry for the guy? As Mike tells Adam: “You don’t need to eat an egg to know it’s bad.â€

Naked City, of course, wasn’t just about characters and plotting. It was also known for its on location setting. This particular episode does not disappoint. There’s a great scene in the Central Park Zoo in which, if you watch carefully, you can get a glimpse of the famous Essex House sign in the background. There are some good subway scenes and a great shot of the old Yankee Stadium.

And if you like neon, there are a couple of great moments shot at night in which we see Manhattan nightspots lit up. We also learn that sometimes, at night, a car may go crashing through a building entrance, a criminal mastermind may have his plans foiled by a man with a conscience, and a good cop may have to use his gun to get rid of a bad one.

“A Death of Princes” is a very good episode with solid writing. Best of all, it features a great performance by Wallach, who seems to be the master of using his eyes to convey mood and meaning. Watch his eyes throughout the episode and you’ll see what I mean. (The entire episode can be seen on Hulu online here.)

Sun 15 Jun 2014

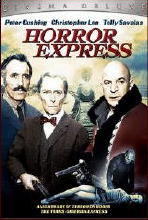

HORROR EXPRESS. Benmar Productions/Granada Films, 1972. A Spanish/British production; released in Spain as Pánico en el Transiberiano. Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, Alberto de Mendoza, Telly Savalas, Julio Peña, Silvia Tortosa, Ãngel del Pozo, Helga Liné, Alice Reinheart. Director: Eugenio MartÃn.

“The following report to the Royal Geological Society by the undersigned, Alexander Saxton, is a true and faithful account of the events that befell the society’s expedition in Manchuria. As the leader of the expedition, I must accept the responsibility for its ending in disaster. But I will leave, to the judgement of the honorable members, the decision as to where the blame for the catastrophe lies…”

I’m sure I’m not the only one, but I love movies that take place on trains, and all but one half of one percent of this one does, so what does that tell you? And any movie with both Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing in it has got to be worth watching, and doubly so when they’re on the same side — well, friendly rivals, I would say.

Christopher Lee plays Professor Saxon, a British anthropologist, on board the Trans-Siberian Express from China to Moscow, along with the frozen body of a monstrous-looking humanoid discovered in a remote Manchurian cave (as if remote and Manchurian never appeared in the same sentence before). A colleague, Dr. Wells (Peter Cushing) is also on board, but only fortuitously so.

Or even luckily so. Both men are needed, as it so happens, since the creature in its sealed crate must be responsible for the series of mysterious deaths that quickly ensue — but how? — even before the train starts off on its long trek through the isolated snow-covered Siberian wasteland — the eyes of the victims sucked purely white, their brains wiped clean, as smooth as a baby’s bottom. (We get to view the makeshift autopsy on the moving train.)

There is an explanation, a science-fictional one, but the real fun is watching a pair of true professionals (Lee and Cushing) enjoy themselves immensely, or so they make us believe. (Cushing’s wife had died just before filming began, and he nearly backed out of his role.) As for Telly Savalas, as a loudly flamboyant Cossack officer (to put it mildly), the less said the better, at least by me.

NOTE: The video link above is of the final four or five minutes only. To see the movie in its entirety, go here.

Sat 14 Jun 2014

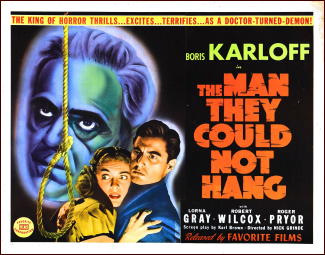

THE MAN THEY COULD NOT HANG. Columbia Pictures, 1939. Boris Karloff, Lorna Gray, Robert Wilcox, Roger Pryor, Don Beddoe, Ann Doran, Jo De Stefani, Charles, Trowbridge, Byron Foulger. Director: Nick Grinde.

If in Night Key (reviewed recently here) Boris Karloff was a bumbling but revengeful old inventor who was seriously wronged, he was at heart a kindly old gentleman with (as I made a point in mentioning) a beautiful daughter. In The Man They Could Not Hang, Mr. Karloff is a scientist, not an inventor, and even before he is serious wronged (see below) he doesn’t have the best of dispositions to begin with.

But after he is hanged (see the title), his quest for revenge upon the jury, the judge, prosecutor, and the members of the police force who helped convict him turns him into a mad scientist whose vengeance is clever, wicked and just plain diabolical.

His crime? That of killing a medical student who had willingly agreed to become the subject of Dr. Henryck Savaard’s latest experiment – a crucial one indeed, one in which the student is put to death under controlled conditions, expecting to waken again by means of a strange, weird-looking apparatus in Savaard’s laboratory.

The police are summoned before the test of the equipment is completed, however, and their intervention means the student cum guinea pig is doomed to a permanent death.

The middle third of the movie is the slowest moving one, taking place as it does in the courtroom, with plenty of room for the prosecutor and Dr. Savaard to speak their views and respond to the other’s. Savaard suggests that being able to bring patients back to life on the operating table would mean more lives saved during surgery; nix on that, says the D.A.: a death is a death, and murder is murder.

The last third of the film could have been the most fun, with many of well-recovered Dr. Savaard’s would-be victims locked up together in a booby-trapped house, and for the most part is it is, but the ending seems rushed. Here (not so coincidentally) is also where the mad scientist’s beautiful daughter comes into play – an essential role, to be sure, but one well telegraphed in advance.

Fri 13 Jun 2014

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

HOLD YOUR BREATH. Christie, 1924. Dorothy Devore, Walter Hiers, Tully Marshall, Jimmie Adams, Priscilla Bonner, Jimmy Harrison, Lincoln Plummer, Max Davidson. Director: Scott Sidney. Shown at Cinefest 26, Syracuse NY, March 2006.

The audience greeted the silent comedy with considerable pleasure. In its own way, it is somewhat bizarre, as cub reporter Dorothy Devore attempts to get an interview from reclusive millionaire Tully Marshall in his well-guarded apartment.

Through a series of ruses, she gains entry and even manages to ingratiate herself when an organ-grinder’s monkey reaches through an open window and makes off with an expensive diamond bracelet, the most recently acquired bauble in Marshall’s collection.

The rest of the film consists of Devore’s hair-raising attempts to retrieve the necklace as the monkey climbs about the building’s exterior, with a detective in hot but somewhat less exposed pursuit, A highlight for the audience was a cameo by Max Davidson as a street pedlar who takes advantage of the crowd gathered to hawk his wares.

Devore is a delight, and this film was one of the comic highlights of the weekend. Sidney also directed the Elmo Lincoln Tarzan of the Apes, as well as another Christie comedy that I’ve seen and liked, Charley’s Aunt (1925). According to the program notes, Devore was the top female comedian on the Christie lot in the 1920s. I don’t find that hard to believe.

Fri 13 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

CLIVE CUSSLER & JUSTIN SCOTT – The Race. Putnam, hardcover, 2011. Berkley, paperback, September 2012.

In The Chase Clive Cussler introduced a new hero in early 20th-Century Van Dorn Agency operative Isaac Bell, and delivered the freshest and most entertaining book he had written in years. In the follow-ups he turned the series over to veteran suspense novelist Justin Scott (The Shipkiller, The Normandie Triangle) who has run with the ball adding to the energetic series that combines Cussler’s love of anything mechanical, Scott’s gift for historical thrillers, and an attractive and entertaining hero to cheer for.

Somewhere between Nicholas Carter and the Nickel Library, a Road Runner cartoon, and a modern Tom Swift, Isaac Bell’s adventures have only gotten better.

The Race was the fourth book in the series (preceded by The Chase, The Wrecker, and The Spy), and has been followed by The Thief and The Striker.

In this one, vicious millionaire Harry Frost attempts to kill his aviatrix wife Josephine’s supposed lover airplane designer Marco Celero. He apparently succeeds, leaving young Josephine, fresh off the farm and enamored with flight penniless. Harry escapes, Marco’s body hasn’t been found, but millionaire newspaper magnate Preston Whiteway is smitten and plans a cross country aviation race for Josephine to win.

That’s where the Van Dorn Detective Agency comes in, because Frost has threatened to kill Josephine, and she needs constant protection. Enter the Van Dorn’s top man, Isaac Bell, who has a violent past history with Frost from the latter’s days as a Chicago tough.

It’s Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines with bullets as well as planes flying, as Bell and his team set out to protect their client from the juggernaut Frost, a giant in a bullet proof vest capable of hiring an army of thugs and gunmen to make sure Josephine never reaches San Francisco.

The books move at a rapid pace and Bell, his boss Van Dorn, his fiancee (later wife) Marion a pioneer film maker, and a cast of regular Van Dorn operatives make for a good team to cheer for usually cast against a villain equal parts Snidely Whiplash, Mr. Hyde, James Bond’s Blofield, and Marvel comics Juggernaut — virtual forces of nature, dangerous, sly, smart, and ruthless.

In addition there is usually a mystery that the reader if not Bell and company knows the solution to, and some good if prosaic detective work that despite the period reminds me much more of my Pinkerton days than Hammett’s Continental Op or Nebel’s Cardigan.

The villain is Wily E. Coyote in these, and Bell the Road Runner one step behind and encountering one setback after the next while pulling the irons out of the fire enough to get to the next set piece. The analogy is particularly good in this one since the villain loses a piece of himself literally in every encounter. I kept waiting for anvil to fall on him or for him to run off a cliff, but he never quite manages it.

There are usually good if lightly drawn secondary characters, a surprise or two (at least they are supposed to surprise readers, whether they actually do is another question), lore about cars, boats, airplanes, guns, railroads, and a thousand other facts from the era that somehow fit in with much more ease than in Cussler’s Dirk Pitt novels, where he has been known to stop mid-book for an extraneous car rally or flight in a vintage airplane that is forced into the plot like a square peg hammered into a round hole with a sledge hammer. Here the details and action blend smoothly and keep the pages effortlessly turning.

This one has everything, running gunfights, vintage cars zooming about, special express trains, early airplanes made of spit glue and fabric, gangsters, gamblers, a passionate Italian beauty to be rescued from a madhouse, a plucky heroine with secrets, a crazy Russian inventor, a shadowy figure with his own agenda, heroic drivers (the word pilot was not in use yet) of vintage planes, and a short course on flying better than the one I took in high school where I learned to fly.

Who wins the race and how, how Bell defeats Frost, Josephine’s secret, the shadow man and his dire scheme, flying, fighting, tornados, thunderstorms, narrow escapes, and daring heroics make sure you never really take time to think too hard about all of it, and why should you? This is pure escapism of a high order, the Rover Boys with guns, dime novels with better prose, barn burners with real burning barns.

In the modern tradition Bell is a Boy Scout with violent tendencies, morally pure, upstanding, a shade pompous, but still attractive and likable. Someone needs to give modern thriller writers a quick course in anti-hero, even straight shooter Tom Mix sometimes played a bandit. But that’s a minor peeve, and what ever the flaws, this is one of my favorite current series.

These shared series are popular now, and Cussler has been joined by James Rollins now along with many others (some posthumously) in these collaborations, but Cussler has three of the best co-writers, in Scott, Thomas Perry (yes, that Thomas Perry the Edgar award winning one), and Jack Du Bruhl. It shows in the quality of the books they produce. These writers had their own successes and readers well before they tied their names with the Cussler brand, and it shows in the quality of the work produced.

Incidentally I chose this one because I found it the least of the series yet, but it is still fun, smart, fast paced, and funny when it means to be. If the worst book in the series is this good you should have an idea how good the best is. Here’s hoping Isaac Bell keeps chugging along in his vintage boats, planes, and automobiles for years to come.

« Previous Page — Next Page »