This first album by this still semi-active garage rock band from the Bay City Michigan area was released in 1966:

February 2017

Sun 19 Feb 2017

Music I’m Listening To: ? (QUESTION MARK) AND THE MYSTERIANS – 96 Tears [Complete Album].

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Sat 18 Feb 2017

A PI Mystery Review by Barry Gardner: JOE GORES – 32 Cadillacs.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews[6] Comments

JOE GORES – 32 Cadillacs. DKA File #4. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1992; paperback, 1993.

It’s been fourteen years since the last DKA from Gores, so long that I’d despaired of another, but here it is, and it’s up for (though in my opinioni doesn’t merit) an Edgar.

Daniel Kearney Associates is a private detective agency operating out of San Francisco. DKA doesn’t do murders as their main source of revenue (though there have been some in previous books), they repossess cars, and do collections and skip traces. In 32 Cadillacs they have the repo case of a lifetime, as no less than 31 new Cadillacs have been purchased by fraudulent means and absconded with, all financed by the same bank. The 32nd is a finny pink ’58.

The scam is being run by Gypsies, who are involved in a plan dealing with the Imminent death of their King (who lies in a hospital in Steubenville, Iowa) and the potential selection of his successor. The story details DKA’s frantic efforts to find the cars, and the machinations of the opposing Gypsy factions as well.

All the old gang is here: Dan Kearney, Giselle Marc, Bart Heslip, and Ballard and O’Bannion. Gores writes bare-bones prose, and manages to keep the story moving forward in a straight line — no mean feat with the viewpoints shifting rapidly among the DKA bunch and various members of the Gypsy gang of miscreants. There is enough characterization that the players seem real, though they will be more so to past readers of the series. Gores did a lot of research into the Gypsy way of life, and the plot is entertaining.

I didn’t like this as much as earlier tales in the series. It lacked their hard edge, and in fact was more of a caper novel, even including a cameo by Westlake’s Dortmunder. The DKA stories are pretty much sui generis, but this wasn’t the best one. Lesser Gores is still worth reading, though.

The DKA File series —

1. Dead Skip (1972)

2. Final Notice (1973)

3. Gone, No Forwarding (1978)

4. 32 Cadillacs (1992)

5. Contract Null and Void (1996)

6. Stakeout on Page Street (2000)

7. Cons, Scams, and Grifts (2001)

Sat 18 Feb 2017

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: TRAINING DAY (2001).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[3] Comments

TRAINING DAY. Warner Brothers, 2001. Denzel Washington, Ethan Hawke, Scott Glenn, Tom Berenger. Director: Antoine Fuqua.

A brief warning, if I may, especially to those of you who have not seen the movie and think you might. In my comments that follow, there will be aspects of the film that may be revealed before you’d like to know about them. This is one of those films that if you know too much before it begins, it will spoil everything for you.

Training Day, the film for which Denzel Washington won an Academy Award for Best Actor, works on two different levels. On the surface, it’s a gritty crime film about two cops. One is a veteran African-American detective, Alonzo (Washington) from the mean streets of South Central Los Angeles. The other, Jake Hoyt (Ethan Hawke) a fresh-faced White rookie from the suburban San Fernando Valley who is not prepared for what will face him on his first day — his training day — working in the narcotics division.

As the movie begins, the viewer goes along with Hoyt as he rides along with the charmingly crude Alonzo as they cruise the mean streets of Los Angeles, encountering rapists, thugs, and drug dealers. Alonzo does his best to tell his green apprentice that unless he’s willing to be a wolf, he’s going to be eaten alive by the criminal element plaguing the city.

That’s one level of the film and it’s not a particularly bad police film. There’s plenty of action, and Washington shows he’s a top American film talent. For an actor who had previously played rather cerebral types or at least heroes, he really does seem to lose himself in the role. No surprise then that he won an Oscar.

But there’s a whole other level to Training Day and that’s one that, from what I can tell, seems to have gone little noticed among critics. And that would be the story unfolding from the point of view of the film’s protagonist, Jake Hoyt.

In many ways, the movie isn’t about Alonzo at all. It’s about Jake’s perception of what is happening — or not happening — all around him. For most of the film, Jake thinks he’s in the company of hothead at best, a corrupt cop at worst. But as things progress, he learns that he has perceived the situation incorrectly all the time. True, Alonzo is a hothead and corrupt, but he’s also been working on a scheme involving Jake from the very first moment that the two men meet in a diner.

Much of the film features scenes in which the two men burst into various apartments and houses. Alonzo knows what to expect inside; Jake does not. For most of the movie, we experience this disorientation from Jake’s perspective. What waits inside these homes? Where is Alonzo taking him? Are the people that Alonzo is shaking down criminals or just innocent people caught up in a web of corruption? Everything seems to be happening so fast that Jake can hardly gain a sense of where he is and what is happening.

Typical of the film noir genre, the movie positions Jake as an object, rather than a subject. He’s seemingly at the whims of a world gone mad, caught up in a continual spiral downward. That is until a coincidence — also a noir trait — ends up saving his life and allows him to regain his footing.

Also key to the plot is the fact that very early on Alonzo forces Jake to smoke marijuana, telling him that if he wants to be a narc, he has to be familiar with drugs. Turns out that it isn’t marijuana at all, but the far deadly and more disorienting PCP. Something else that not only changes Jake’s literal perception of urban Los Angeles, but becomes central to the wildly devious plan Alonzo has in mind.

After putting up with Alonzo’s increasingly crazed behavior for a one bruiser of a day and discovering how Alonzo has set him up as a patsy for his plans, Hoyt finally sets upon a course of action that will ultimately lead to his would-be mentor’s final downfall.

Fri 17 Feb 2017

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: BABES IN BAGDAD (1952).

Posted by Steve under Films: Comedy/Musicals , Reviews[3] Comments

BABES IN BAGDAD. United Artists, 1952. Paulette Goddard, Gypsy Rose Lee, Richard Ney, John Boles, Sebastian Cabot. Written by Joe Ansen and Felix Feist. Directed by Edgar Ulmer.

You can gauge the quality of a fabric by the way it wrinkles. In this case Paulette Goddard, in the sputtering last days of her movie career, brings a surprising vigor and cheerfulness to what must have seemed like a desperate cheapie.

There’s some real talent involved here, though. Ms Goddard, a delightful presence by herself, worked brilliantly with Charlie Chaplin, Burgess Meredith, Mitchell Leisen, Jean Renoir and Cecil B. de Mille. John Boles was never an electrifying screen presence (he drops out of Frankenstein halfway through and no one notices!) but he had a colorful background as a spy for the allies in World War I and apparently came out of retirement just for this. Director Edgar Ulmer helmed some genuine masterpieces, and Gypsy Rose Lee… well she was a better actress than anyone with a body like that really needed to be.

And here they are, all together in Spain (a lot of fading stars and maverick filmmakers found themselves in Europe at the time; think of Welles, Chaplin, Flynn….) amid a jumble of cardboard sets and costumed extras trotting through the Arabian Nights and doing it with real panache.

Edgar Ulmer shows a remarkable touch for humor — unexpected from a director famed for lugubrious stuff like The Black Cat, Detour and Bluebeard — moving his camera fluidly through palaces, harems and marketplaces with assurance, and pacing the comic scenes at a brisk tempo.

Unfortunately, there’s a story to get through here, of the sort that is generally and mercifully described as El Stinko. Something about neglected harem girls lobbying for equal rights, a conniving tax collector, hero Richard Ney falling for defiant slave girl Goddard, switched identities… it all gets a bit hard to follow and frankly not worth the effort.

The film itself is a pleasure to watch, however. Ulmer keeps it interesting to look at, Sebastian Cabot throws in a fine bit as a eunuch, you can glimpse Christopher Lee (if you don’t blink) as a slave trader. And Ms. Goddard plays it with all the enthusiasm she gave to movies like Ghostbreakers and Modern Times: writhing, struggling and cursing as a reluctant captive, playing for laughs as a scheming vixen, and finally simply sweet and seductive for the happy ending.

Babes in Bagdad isn’t an easy film to find, and the print I finally located is pretty dismal, but it’s still fun and, in its own way, a fitting coda to a memorable career.

Thu 16 Feb 2017

DONALD HAMILTON – The Poisoners. Matt Helm #13. Fawcett Gold Medal M2764, paperback original; 1st printing, March 1971.

This was the first Matt Helm to be publishers in the 1970s, and the one in which some fans have said the series began to lose its initial innate hardboiled essence. While I have not made a point of reading them in order, I would tend to agree. This one clocks in at an acceptably compact 224 pages, but for most of the book the plot doesn’t build up any momentum, and Helm’s digressions upon whatever he feels the need to digress upon do little to help.

This one begins with Helm being asked to cut short his r&r leave in New Mexico and head to Los Angeles where a female agent he had personally recruited for his undercover US agency has just been killed. His assignment, find out who and why and do something about it.

And of course the case expands dramatically from there. The title has two meanings, the first of which I can tell you about: the rumored illegal import of cocaine from Mexico. The second is the one the story is really about, and since its secret is essential to the tale, I won’t tell you much about it, but I will say that I didn’t buy into it any further than I can throw myself from here to there.

There are a number of women in the story, all attractive of course, not all of them are on our side. Question: which are which? There also a notorious criminal assassin involved, but all that is known about him (or her!) is his code name. All this intrigue keeps a man sharp, though, and Matt Helm is still the man to do it — no doubt about it!

Thu 16 Feb 2017

Music I’m Listening To: VON RYAN’S EXPRESS “Allergic.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

I don’t know much about this big band soul-funk group. They produced one self-titled LP in 1971, and that was all. This song comes from that album.

Wed 15 Feb 2017

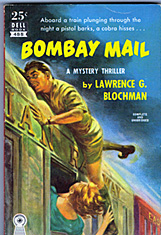

A 1001 Midnights Review: LAWRENCE G. BLOCHMAN – Diagnosis: Homicide.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[15] Comments

by Bill Pronzini

LAWRENCE G. BLOCHMAN – Diagnosis: Homicide. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1950. Pocket Book #793, paperback, 1951. Television: CBS, 1960, nine-episode summer replacement series, with Patrick O’Neal (Dr. Coffee), Phyllis Newman (Doris Hudson), Cal Bellini (Dr. Mookerji), Chester Morris (Max Ritter).

Although most of his work is (regrettably) long out of print and he is little known among modern readers, Lawrence G. Blochman was an innovative and popular writer for more than four decades. His early novels and short stories had foreign settings, primarily India, where he spent several years in the 1920s as a newspaperman.

Bombay Mail (1934), his first and probably most accomplished novel, is set on board an Indian train; features one of his many series characters, Inspector Leonidas Prike of the British CID; and is one of the best of that intriguing subgenre, the railway mystery. Two other Prike novels, Bengal Fire (1937) and Red Snow at Darjeeling (1938), are also good, as is Blow-Down (1939), a non-series suspense/adventure novel set in a sleepy Central American banana port.

Blochman’s most notable creations, however, are his numerous short stories (for such magazines as Collier’s and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine) and one novel featuring Dr. Daniel Webster Coffee, pathologist of the Pasteur Hospital in mythical Northbank, New York. Coffee was the first pathologist detective in crime fiction, the forefather of TV’s Quincy, and his cases have a uniform sense of realism as a result of Blochman’s interest and research in forensic medicine. Diagnosis: Homicide, the first of two Dr. Coffee collections, is of sufficient import that Ellery Queen included it as the lO6th and final entry on his Queen’s Quorum list of most important volumes of detective short stories.

The eight novelettes in this book are what might be called “forensic procedurals.” Coffee’s chief criminological weapons, as Ellery Queen has pointed out, are modern (circa 1950) laboratory procedures in pathology, chemistry, serology, microscopy, and toxicology.

With these — and the help of his assistant, Dr. Motilal Mookerji, on scholarship from Calcutta Medical College, and police lieutenant Max Ritter — the good doctor solves such baffling cases as the death of a woman after an apparently simple appendectomy (“But the Patient Died”); the strange case of a woman who hears a baby crying in the night, even though there is no baby in her house (“The Phantom Cry-Baby”); and the murder of a doctor to cover up one of the oddest rackets in medical (and criminous) history (“Brood of Evil”).

The second Dr. Coffee collection, Clues for Dr. Coffee (1964), is likewise excellent and worth seeking out. Somewhat less successful is the only novel featuring the pathologist and his sidekicks, Recipe for Homicide (1952); Coffee’s talents, as Blochman himself seems to have realized, are better suited to the short-story form.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 15 Feb 2017

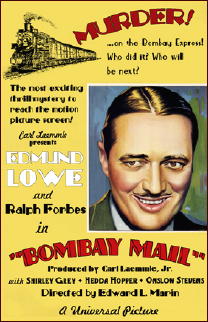

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: BOMBAY MAIL (1934).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[3] Comments

BOMBAY MAIL. Universal Pictures, 1934. Edmond Lowe, Ralph Forbes, Sally Grey, Hedda Hopper, Onslow Stevens, Jameson Thomas, Ferdinand Gottshalk, Brandon Hurst, John Davidson, Walter Armitridge, John Wray, Georges Renavent. Screenplay: Tom Reed, based on the novel by Lawrence G. Blochman. Director: Edwin L. Marin.

It’s hard to imagine what Hollywood would have done for detectives in the 1930’s without William Powell and Edmond Lowe. There is little doubt movie-goers would have been worse off.

Here Lowe is Inspector Dyke (Pryke in the novel, and the change still doesn’t avoid some juvenile innuendo) of the Indian Police who has his hands full when Sir Anthony Daniels (Ferdinand Gottshalk), Governor of Bengal, is murdered with cyanide on the Bombay Express en-route to retirement. He can’t hold up the Express so he determines to investigate during the remaining journey to Bombay.

And he has his hands full, with a train load of red herrings, many with motives to kill the late governor, including Lady Daniels (Hedda Hopper) who argued with her husband about his flirtation with a Russian opera singer and happens to collect butterflies and worse seems to have misplaced the cyanide used to euthanize them; Beatrice Jones of Canada (Sally Grey), who people keep mistaking for Sonia Smeganoff, the White Russian opera singer who apparently was a prostitute in Calcutta; John Halliday (Onslow Stevens) an American miner who desperately wanted to see the Governor and is carrying valuable sapphires about in his tobacco pouch.

And there are more: R. Xavier (John Davidson) a mysterious Eurasian who will do anything to steal the jewels from his former partner, Halliday, and who, hired a mysterious Italian, Martini (John Wray) to steal them; Dr. Maurice Renoir (Georges Renavent) a French expert in toxins who is unusually protective of his medical bag.

Still more: the Maharajah of Zungara (Walter Armitridge) traveling with Daniels to plead to remain in control of his little kingdom; Pundit Garnath Chundra (Brandon Hurst) a Ghandi like revolutionary with no love of the British; the Governors military advisor Captain Gerald Worthing (Jameson Thomas) facing charges for being seen in the company of a certain Russian opera singer; and the Governor’s secretary Captain William Luke-Paton, who has a thing for fast, and slow, horses.

There are bodies hidden in lavatories, screams in the night, an assassination and frameup, a pesky cobra, lies within lies, and a straight forward gathering of the suspects as the train nears Bombay and time runs out to identify the murderer.

Dated as it is, this is an entertaining murder on a train film with an outstanding cast, and fortunately closer than most to the fine book (first in the Inspector Pryke series) it is based on. Lowe is ideal as the tough leering no nonsense sleuth, and both Stevens and Grey have some fun as people thrown together by the sheer amount of lies they are telling and mutual attraction. There is a harrowing crossing of the rooftops of the speeding train, some clever escapes, and a tense confrontation with a King cobra in a small railway suite.

All and all it is just about a perfect example of what it is, a fast-paced Hollywood murder mystery from the classic era.

Tue 14 Feb 2017

A PI Mystery Review: BRIDGET McKENNA – Caught Dead.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , ReviewsNo Comments

BRIDGET McKENNA – Caught Dead. PI Caley Burke #3. Berkley, paperback original; 1st printing, February 1995.

The ending of book two in this series must have been fairly spectacular. At the beginning of this one, private eye Caley Burke’s boss won’t let her come back to work for a second week until she agrees to go in for counseling to see why she can’t sleep at nights. Not too many people ever shoot and kill someone, even in self defense.

She agrees, but she decides to take a case on her own as her own form of self-help therapy. The son of her favorite waitress at her usual breakfast spot hires her to find out who his father is. His mother won’t tell him. Not only this is a situation in which you should be careful what you ask for, but it’s one which goes far beyond that. The very next day his mother is arrested for the brutal slaying of her sister.

We are in Sue Grafton territory here. Caley lives in s medium-sized town in central California, lives alone and likes it that way, and when she gets her teeth into a case, she doesn’t let go. She pries and she pries, and bit by bit, the secrets begin to loosen and come flying off.

Caley doesn’t have the flair of Kinsey Millhone, though. She’s effective but is a lot more workmanlike in her pursuit for the truth. There are a lot of suspects in the case, all the more so as the dead woman was intensely disliked by everyone in town, including her family. This means, of course, that Caley has to ask a lot of questions. Surprisingly, she gets a lot of people to answer.

Overall, better than average, with decent clueing, more than two-dimensional characters, and an ending that just may catch you by surprise. (It’s intended to.) I’d read the next one, but after three books, there never was a fourth. I’ll have to go back and see what I missed in the first two.

The Caley Burke series —

Murder Beach (1993)

Dead Ahead (1994) Nominated for a Shamus award.

Caught Dead (1995)

Tue 14 Feb 2017

Music I’m Listening To: TOM RUSH – Got a Mind to Ramble [Complete Album].

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Tom Rush’s second album, from 1963: