November 2017

Monthly Archive

Mon 13 Nov 2017

Posted by Steve under

Books NotedNo Comments

Scheduled for publication from Stark House Press in March of next year:

The strange island story utilizes island locations to examine human society and human nature, taking the reader on a journey into the weird, the bizarre, and the unsettling. Nineteen classic tales from Arthur Conan Doyle, Julian Hawthorne, Jack London, H. P. Lovecraft, M. P. Shiel, John Buchan and more; plus one new story from the editor himself!

Sun 12 Nov 2017

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

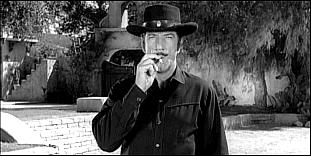

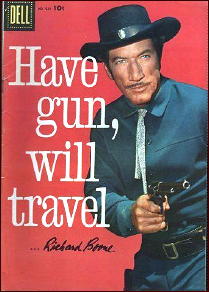

HAVE GUN – WILL TRAVEL. CBS, 1957-1963. 225 30 minute episodes. Richard Boone (Paladin), Kam Tong (Hey Boy). Created by Herb Meadow and Sam Rolfe.

I picked up several episodes of Have Gun – Will Travel a while back and found them, within their limitations, quite enjoyable. The Half-Hour Dramatic Series is nowadays a Lost Art, and it was interesting to see it in practice again.

Quick cuts, elliptical storytelling and tight focus might lead one to expect these would be fast-paced affairs, but they aren’t at all. You see, it’s much cheaper to advance the plot by photographing two actors talking in a room, so there’s a lot of that going on here. Long journeys and even grueling Desert Treks are suggested by about ten seconds of footage, and Fight Scenes, for the most part, are short and to the point. I’ve never seen so many guys knocked out by one punch in all my life, and I wonder if this simplistic approach to Conflict Resolution might have had some effect on my bidding mind in those days.

Anyway, the high point of the series is and always was Boone’s tough, intelligent acting, back in the days when he was Lean and Hungry, and when scriptwriters could let him actually get violent from time to time. Those familiar with Boone’s later acting — particularly the patently phoney, self-indulgent portrayal of The Drawling Cowpoke from Hec Ramsey, who always talked tough but never actually did very much — should get to see him in these.

Sat 11 Nov 2017

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THERE’S ALWAYS A WOMAN. Columbia, 1938. Joan Blondell , Melvyn Douglas, Mary Astor, Frances Drake, Jerome Cowan, Robert Paige, Thurston Hall. Director: Alexander Hall.

CHANDU THE MAGICIAN. Fox Films, 1932. Edmund Lowe (Chandu/Frank Chandler), Irene Ware (Princess Nadji). Bela Lugosi (Roxor). Based on the radio serial of the same title. Cinematography by James (Wong) Howe. Art direction by Max Parker. Directors: William Cameron Menzies and Marcel Varnel.

The high point of Monday morning’s screenings was There’s Always a Woman, starring Joan Blondell and Melvyn Douglas as a husband-and-wife team who split up professionally and then, separately, have a go of solving the murder of Mary Astor’s husband (played by Lester Mathews), Blondell’s scatterbrained zaniness proved to be a good match for Douglas’s more conventional detecting as an investigator for the D.A.

My choice of top overall pick for the convention, however, would probably be Chandu the Magician. Edmund Lowe stars as Chandu, with Bela Lugosi, lithely clad in close-fitting black sweater and slacks, as Roxor, the “malignant” super-villain, ready to reduce humanity to an anarchic mob, which he would command as ruler of a (much-reduced) universe.

Not for Roxor the imperial trappings of Ming the Merciless in the Flash Gordon serials. It’s power he wants, and it’s his burning ambition — along with his magnetic eyes — that makes Roxor a more menacing villain than Charles Middleton’s Ming.

Sat 11 Nov 2017

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

VERA CASPARY – Laura. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1944. Reprinted many times, including: Bestseller Mystery #B74, paperback, no date stated. Popular Library #284, paperback, 1950. Dell D188, paperback, Great Mystery Library #3, 1957. Avon, paperback, 1970. The Feminist Press at CUNY, softcover, 2005. Film: 20th Century Fox, 1944. TV adaption: Season 1, episode 2 of The 20th Century-Fox Hour, as “A Portrait of Murder,” 19 October 1955. TV movie: ABC, 24 January 1968 (co-screenwriter: Truman Capote). [See also the comments.]

The main strength of Vera Caspary’s writing is her depth of characterization; in fact, in many of her mysteries the actual crime takes a back seat to her detailed studies of the persons involved. In this, her first novel, the persona of Laura Hunt, the heroine- initially thought to have been the victim of a brutal murder is so well described that the reader can visualize her and anticipate her actions and reactions long before she appears on the scene.

The other principals — a crime writer and close friend of Laura’s, and the investigating officer who finds himself falling in love with his image of her — are likewise drawn in meticulous detail, through the use of their individual narrative voices. (The story is told in sections, each from the viewpoint of one or the other of the main characters.)

The story they tell is basically a simple one. A young “bachelor girl,” Laura Hunt, has been shot to death in her apartment in Manhattan’s East Sixties.She took the force of the blast in the face, and is virtually unrecognizable except for her attire. Mark McPherson, a police officer with a distinguished record, is assigned to the case and acquires much of his knowledge of Miss Hunt from her friend, a sexually amorphous writer named Waldo Lydecker.

There was a fiance in Miss Hunt’s life — an impoverished copywriter from the ad agency where she worked; and an aunt who is quick to complain about the fiance’s shiftlessness — and to use him when convenient. As McPherson delves further into Laura Hunt’s life, he becomes entranced with the dead woman, a fascination that Lydecker, who narrates the first section, notices and plays upon.

When McPherson takes up the narrative, we find that Laura is not really dead; she had loaned her apartment to a model frequently used by her agency and gone away to her summer cottage for a few days’ contemplation before her impending marriage. McPherson’s attention is now focused on the question of who killed the ordinary little model who was temporarily using Laura’s apartment, and his suspicions eventually point to Laura herself The ending, narrated by McPherson, with an intervening section told by Laura, is predictable, but completely satisfying.

Laura was made into a classic suspense film of the same title, starring Dana Andrews, Clifton Webb, and Gene Tierney, and directed by Otto Preminger, in 1944. In another notable novel, Evvie (1960), Caspary’s characterization of a genuine murder victim is even more sharp and haunting than that of Laura Hunt. And her mastery of the deviant but still socially accepted personality is demonstrated to great effect in Bedelia (1945) and The Man Who Loved His Wife (1966).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 10 Nov 2017

LADY GANGSTER. Warner Brothers, 1942. Faye Emerson, Julie Bishop, Frank Wilcox, Roland Drew, Jackie C. Gleason, Ruth Ford. Based on the play Women in Prison by Dorothy Mackaye and Carlton Miles. Director: Robert Florey (as Florian Roberts).

A previous movie based on Dorothy Mackaye’s play was entitled Ladies They Talk About, a pre-Code film from 1932 starring Barbara Stanwyck and Preston Foster, also from Warner Brothers. Not having seen the earlier film, I can’t say for sure, but my sense is that Lady Gangster is by far the tamer of the two.

Faye Emerson plays Dot Burton, a would-be actress who agrees to help a gang of bank robbers pull off their latest job. When the heist goes awry, she’s the only one who’s caught, and even though Kenneth Phillips (Frank Wilcox), a crusading radio commentator knows her from their youth, tries to help, his effort are of no avail, and off to women’s prison she goes.

But not before she makes off with the loot ($40,000 worth) and hides it away with her landlady for future bargaining power. Even though in prison, not only do both the police and the gang want to know where the money is, but there is an on-and-off romance between Phillips and Dot Burton, complicated by many misunderstandings on both sides.

It isn’t much of a story, but even though it’s a low budget movie, it’s from Warner Brothers, which means the production values are significantly higher than anything that ever came from a Poverty Row studio. It was interesting for me to see Faye Emerson in an actual movie role. She did just fine, but until now I knew her almost exclusively from her career on TV after the movies, especially game shows such as I’ve Got a Secret.

Also of note was Jackie Gleason as a getaway driver for the gang, and a fellow who when I saw him slouching on a couch as Phillips’ assistant, I said to myself that he reminded me of Paul Drake on the Perry Mason TV series. Unknown to me at the time, as he wasn’t listed in the credits, that’s who he really was (William Hopper, billed as DeWolf Hopper).

Fri 10 Nov 2017

M. E. CHABER – The Flaming Man. Milo March #18. Holt Rinehart & Winston, hardcover, 1969. Paperback Library 63-353, paperback; “Milo March #9”; June 1970. Cover art by Robert McGinnis.

Insurance investigator Milo March’s assignment in The Flaming Man is to investigate the death of one of Intercontinental Insurance’s clients in a department store fire during the Watts riots in Los Angeles.

I’ve always been a fan of this series, but I seem to have never read this one until now. It’s a short book, just over 150 pages in the paperback edition, and what I said in paragraph one summarizes the story completely. There is not a single surprise or unexpected event in the entire book.

And if you cut out the references to drinking, the book would be at least 20 pages shorter. Milo March is one of those guys who could really put it away. For breakfast, lunch, dinner, bedtime and every other half hour in between, another drink. From one bar to another, it seems, nonstop. (March does find time, while solving the case, for a good-natured dalliance with a well-endowed stripper lady. They make a good couple. She knows how to toss them down as well.)

The cover is nice, but the reading is awfully slow going. This is the kind of book that makes me tell myself that I could do better, and what’s worse I know I couldn’t.

The Milo March series —

Hangman’s Harvest (n.) Holt 1952 [California]

No Grave for March (n.) Holt 1953 [Berlin]

As Old As Cain (n.) Holt 1954 [Ohio]

The Man Inside (n.) Holt 1954 [Madrid]

The Splintered Man (n.) Rinehart 1955 [Berlin]

A Lonely Walk (n.) Rinehart 1956 [Italy]

The Gallows Garden (n.) Rinehart 1958 [Caribbean]

A Hearse of Another Color (n.) Rinehart 1958 [New Orleans, LA]

So Dead the Rose (n.) Rinehart 1959 [Berlin]

Jade for a Lady (n.) Rinehart 1962 [Hong Kong]

Softly in the Night (n.) Holt 1963 [Los Angeles, CA]

Six Who Ran (n.) Holt 1964 [Rio de Janeiro, Brazil]

Uneasy Lies the Dead (n.) Holt 1964

Wanted: Dead Men (n.) Holt 1965

The Day It Rained Diamonds (n.) Holt 1966 [Los Angeles, CA]

A Man in the Middle (n.) Holt 1967 [Hong Kong]

Wild Midnight Falls (n.) Holt 1968 [Moscow]

The Flaming Man (n.) Holt 1969 [Los Angeles, CA]

Green Grow the Graves (n.) Holt 1970

The Bonded Dead (n.) Holt 1971 [Miami, FL]

Born to Be Hanged (n.) Holt 1973 [Nevada]

Thu 9 Nov 2017

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

ANN CLEEVES – The Seagull. Inspector Vera Stanhope #8. Minotaur Books, US, hardcover, September 2017. First published by Macmillan, UK, hardcover, 2017.

First Sentence: The woman could see the full sweep of the bay despite the dark and the absence of street lights where she stood.

An old enemy of Insp. Vera Stanhope, John Bruce asks that she visit him in prison where she helped put him. He wants to cut a deal: information on the whereabouts of the body of Robbie Marshall, a long-missing hustler in exchange to Vera looking out for his daughter and grandchildren. There is a very personal element to this case for Vera as Bruce, Marshall, and a man known only as “the Prof,†were close friends of her father, Hector Stanhope, bringing back memories Vera would prefer remain buried.

Cleeves creates such a strong sense of emotion— “Sometimes it felt as if her whole life had been spent in the half-light; in her dreams, she was moonlit, neon-lit, or she floated through the first gleam of dawn,†—and place— “The funfair at Spanish City was closed for the day, and quiet. She could see the silhouettes of the rides, marked by string of coloured bulbs, gaudy in full sunlight, entrancing now.â€

Those who follow the BBC television series Vera and may be disappointed by the departure of some characters, it’s nice to see that her assistants Holly and Joe are still here in the books. The description of Vera’s team is done in terms of their relationships to Vera. What is lovely is her understanding of what drives them, each member’s strength and what motivates them. Vera and Joe’s visit to the mother of a missing man is a sad reminder of the pain through which families go without the closure of knowing what happened.

There is honest police work here. The investigation is conducted by legwork as well as technology; getting out and talking with people. The case is worked step-by-step, without flash.

Vera’s self-awareness is admirable— “then she thought she was making a drama of the situation. She always did.†Yet, to her— “…the law matters. All those little people you despise so much have to abide by it, and so do you. So do I.â€

The Seagull is such a good book. Beyond the excellent plot, what one really cares about is Vera and her team.

Rating: Excellent.

The Vera Stanhope series —

1. The Crow Trap (1999)

2. Telling Tales (2005)

3. Hidden Depths (2007)

4. Silent Voices (2011)

5. The Glass Room (2012)

6. Harbour Street (2014)

7. The Moth Catcher (2015)

8. The Seagull (2017)

Thu 9 Nov 2017

HUGH PENTECOST – The 24th Horse. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1940. Popular Library #82, paperback, no date stated [1946]. CreateSpace/Bold Venture Press, softcover, May 2016.

This is the second of five recorded mysteries solved by Inspector Luke Bradley of New York City’s Homicide Division. He’s called in when the young boy friend of a girl finds the girl’s sister’s body stuffed in the rumble seat of the car belonging to his girl friend. Complicating matters is the fact that his girl friend’s sister used to be his girl friend, but after he broke up with her a few days earlier, she had mysteriously disappeared.

It turns out that the dead girl, while quite beautiful and popular with the men in her life, also had an unpleasant streak to her personality. Bradley soon suspects that she was not averse to a little blackmail. A letter left to be sent to the police after her death turns out to be blank. It then becomes a matter of not only who had a motive but who had access to the desk when the letter was kept.

The background for this vintage detective novel is that of indoor steeplechase racing, with the title referring to the stages of 24 horses that people learning to jump must master, with increasing degrees of difficulty. There are, in the end, also 24 clues that Bradley gives to a friend, that when interpreted correctly, will add up the killer.

Pentecost, aka Judson Philips, was a long time pulp writer, so it’s no surprise that when he turned his hand to writing book-length fiction, such as this one, the results were smoothly written, with solidly constructed characters.

That it’s no classic that fans of fair play detective fiction will remember, is probably due to the fact that — in spite of the clues — does it not quite establish what Bradley knew and when he knew it. The killer is quite obvious, too, if you take the time to think about it.

The Inspector Luke Bradley series —

Cancelled in Red (n.) Dodd 1939

The 24th Horse (n.) Dodd 1940

I’ll Sing at Your Funeral (n.) Dodd 1942

The Brass Chills (n.) Dodd 1943

Secret Corridors (na) Century 1945 [also with Dr. John Smith]

Wed 8 Nov 2017

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

FIGURES IN A LANDSCAPE. Twentieth Century Fox, UK, 1970. National General Pictures, US, 1971. Robert Shaw, Malcolm McDowell. Screenplay: Robert Shaw. based on the novel by Barry England. Director: Joseph Losey.

Figures in a Landscape isn’t exactly the type of movie to grow on you, but it’s one that lingers in your mind for a while after you’ve finished watching. Part of this has to do with the fact that, at least on one level, not all that much happens in the movie.

There are two primary characters – the only two characters with real dialogue – and the movie follows their journey through fields, villages, canyons, and mountain peaks as they attempt to outrun a mysterious black helicopter in a deadly game of cat and mouse. The other reason that the film lingers in your mind’s eye after watching is because there’s actually a lot happening in the movie, albeit on a symbolic level. Indeed, much of the movie is an extended metaphor about the basic human quest to be free from constraints and rules. The movie also has a lot to say about warfare, borders, and government power.

Robert Shaw and a young Malcolm McDowell portray two British men in a hostile territory. We don’t know who they really are or why they are on the run and who may be on their trail. The movie opens with the two of them in handcuffs trying to evade an omnipresent black helicopter constantly hovering above them. It soon becomes clear that the helicopter, operated by two men dressed all in the black, is not simply interested in capturing the duo. It, or at least its pilot, wants to torment them.

As the film progresses, the viewer learns that Shaw’s character, Mac, is a gruff, crude sort, while McDowell’s character, Ansell, is a more sensitive type whose good with the ladies and who isn’t afraid to cry. Both men need each other to evade the helicopter and, even though they clearly have little in common, decide to forge a partnership for the time being.

Their journey takes them through all sorts of terrain. It’s here that Joseph Losey’s direction really shines. The natural vistas presented here are breathtaking, and all serve to remind the viewer that duo are small figures upon a larger naturalistic canvas.

But what is the point of all this? For a movie rich with existential themes and which attempts to say a lot by saying very little, the dialogue is eminently forgettable. Although the banter between the two at times resembles that of a bickering old married couple, neither of duo has all that much interesting to say about their plight. More is said by their actions than by their words. This is particularly true for Mac (Shaw). By the time the two men are almost free from the helicopter, he is increasingly mentally unbalanced and erratic.

All told, Figures in a Landscape definitely isn’t a great movie, but it’s a good one. It’s boldly experimental and benefits from not only Losey’s direction, but from exceptional cinematography and a haunting score by Richard Rodney Bennett.

Wed 8 Nov 2017

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

ERNEST LARSEN – Not a Through Street. Grove Press, paperback; 1st “Black Cat” printing, 1986. First published in hardcover by Random House, 1981.

Something I didn’t know: Grove Press once published a private eye novel. (And perhaps others?) Something else I didn’t know (or didn’t remember): this book was nominated for an Edgar for Best First Mystery in 1982. Larsen must have taken the award and run. He (as far as I know) never published another mystery or crime novel, even though this one ends with Emma Hobart, an ex-radical cab driver, nicely set up as a semi-legal, unofficial, street level PI.

And that’s what in essence she is throughout this book as well, except that her only client is herself, and her boy friend, who is seriously involved in an “accident” concerning her taxi and two men who desperately want the film in his camera.

It starts slowly. The first two chapters are spent with two people sorting out their feelings for each other, obviously in love but not able to say it to each other at the right time. The blurb on the cover of the paperback edition calls this an invasion of “Chandler territory,” but as far as this beginning is concerned, I have a strong feeling that collectors of the complete works of Raymond Chandler would not care for it at all.

This is “hippie country,” no doubt about it, a leftover from the 60s, with dialogue that every so often sounds like psychological/philosophical jargon — sorry, I can’t tell which — and there is a definite haze of psychedelia clinging to the rest of the story, which is all about some dastardly corporation plot that was cooked up during the war in Vietnam. It’s no wonder that Grove Press decided it was their cup of tea.

Originally published by Random House in hardcover, this book may prove to be hard to find. If you ever spot a copy, though, it’s worth picking up. The plot is a relatively shallow one, but Emma is a tough lady, and even though this particular adventure takes a lot out of her, it’s a shame there wasn’t ever another one.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File #23,, July 1990 (somewhat revised).

[UPDATE] It is a correct statement that this was the only work of crime fiction written by Ernest Larsen. I do not know if it is the same Ernest Larsen, but he may also be the author of a well-regarded work of non-fiction covering the movie The Usual Suspects in considerable detail (BFI, 2002).

« Previous Page — Next Page »