February 2018

Monthly Archive

Tue 20 Feb 2018

EDWARD D. HOCH “The Problem of the Miraculous Jar.” Dr. Sam Hawthorne. First published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, August 1996. Collected in All But Impossible (Crippen & Landru, 2017). Reviewed by Mike Tooney here. (Thanks to Randy Cox for providing this information.)

It is November 1939 and even in the small New England town of Northmont, rumors of the impending war are getting stronger by the day. When a married couple are given a welcome home party after their return from a trip to Europe and the Holy Land, no one expects that someone will die later that same evening, including Dr. Sam Hawthorne, one of the attendees.

Cause of death: cyanide in a jar brought back as a gift from Cana, the site of Jesus’s first miracle, the transformation of water into wine, a feat that seems to have been duplicated here, except that in this case the wine (which was not in the jar when the party was over, only water) is found the next day to have been tainted with poison.

Question: How could anyone change water into poisoned wine inside a locked house surrounded by unmarked snow?

Answer: It’s a damned good trick, that’s what it is. Ingenious, in fact, until you know the answer, and then it’s dumbfoundedly easy.

Except only on occasion, Hoch wasn’t the greatest wordsmith in the world, but his plain-spoken style of writing has to be a lot more difficult to duplicate than you’d think it would be. I also think there is enough plot — with lots of characters complete with backstories, motives, false trails and the like — to fill a complete novel.

Ingenious, too! Or did I say that already?

Tue 20 Feb 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

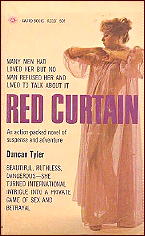

DUNCAN TYLER – Red Curtain. Beacon 205, paperback original; 1st printing, 1959. Award A202F, paperback reprint, 1966.

Obscure books, especially those that are either detective or mystery fiction, have always been favorites of mine, and here is one so obscure that [as of the time this review was first written], Al Hubin had not yet heard of it. What’s even more interesting is that the copyright is in the name of Don Smith, who was soon to become the author of a long series of “Secret Mission” espionage thrillers. While I own about half of them, I’ve never read any, but I’ve always assumed that the Phil Sherman starring in them was some kind of super-agent in the James Bond mode.

Why I am bringing this all out is that there is a Philip Sherman in this book as well, but he’s not a super-agent of any kind, at least not yet. He is an American business man working in Europe who naively gets suckered into some shady business transactions with the Russians, and when things go badly, he naively (again) attempts to break his partner out of a Russian labor prison. This in a country where he doesn’t even speak the language.

If you were to see the front cover [of the Award edition], you would also know there is a woman involved, but not nearly as much as the back cover would have you believe. The last few chapters make the rest of the book worth reading, but if a lot of action is what you might be looking for, the early going is awfully sluggish and slow. It seems to be an accurate peek at life behind the Iron Curtain for its time, however, and maybe that’s the greatest value it ever had.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File #23, July 1990 (slightly revised).

Mon 19 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

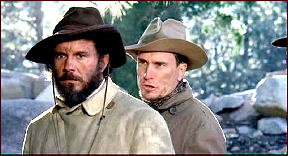

THE GREAT NORTHFIELD MINNESOTA RAID. Universal Pictures, 1972. Cliff Robertson, Robert Duvall, Luke Askew, R.G. Armstrong, Dana Elcar, Donald Moffat, Elisha Cook (Jr.), Royal Dano. Screenwriter-Director: Philip Kaufman.

Filmed in a style that approaches cinéma vérité, Philip Kaufman’s The Great Northfield Minnesota Road has a quasi-documentary feel to it, providing the viewer with an experience that’s almost akin to watching an historical recreation. The movie isn’t so much about plot as it is about atmosphere and, more significantly, about its portraiture of both outlaws and ordinary townsfolk.

Indeed, when it’s at its best, the movie, with its naturalistic performances and lack of artifice allows the audience to be temporarily transported to a small, calm Midwest town in the year 1876 and the midst of great cultural and technological changes.

Enter the outlaws who will wreak havoc in the town. Cliff Robertson and Robert Duvall star, respectively, as Cole Younger and Jesse James in this superbly constructed feature about the Younger Gang’s last and final bank robbery that occurred in the town of Northfield, Minnesota. Both actors portray their characters as both instigators of events and as individuals able to make the most out of life’s circumstances and opportunities after the Confederate loss in the Civil War.

The two are technically in cahoots, but they have very different personalities. Cole is the more introspective of the two; Jesse is the more reckless of the two and betrays a real hatred for the North. He’s also not fully to be trusted. Case in point: when Jesse learns that Cole’s sights are set on Northfield, he attempts to get there before Cole is fully recovered from being wounded in an ambush. Cole, for his part, seems just as intrigued by the societal and technological changes he witnesses in Northfield as he is by his upcoming final bank robbery.

Be on the lookout for the beautiful sequence, filmed documentary style, in which he watches a rudimentary baseball game being played on the outskirts of town with Allen (Dana Elcar), one of the town elders. The message is delivered in a most subtle manner, but it’s abundantly clear. The era of gunslingers is fading away, the anarchic spirit represented by the Younger and James gangs will soon to be replaced by a new, more orderly national pastime, one that will eventually unite a formerly bitterly divided union.

Some might argue that such a sequence takes the viewer out of the film and that it is unnecessary to the plot. But it’s moments like these –and there are a few of them scattered throughout the picture—that are what makes The Great Northfield Minnesota Road stand out from the rather bloated pack of cinematic representations of Cole Younger and Jesse James.

Sun 18 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

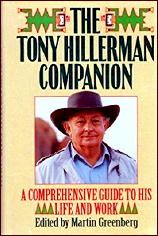

MARTIN GREENBERG, Editor – The Tony Hillerman Companion. HarperCollins, hardcover, 1994; paperback, 1995.

Well, the photo on the dust jacket finally provided confirmation from my wife — Tony Hillerman and I resemble each other. I think it’s the ears.

The Companion contains several sections, the first two being a book-by-book synopsis of Hillerman’s detective novels by Jon Breen, and then a lengthy 1993 interview with Hillerman by Breen. Then there is an article chosen by Hillerman on the Navajos, a section on Navajo Clan names, and then the longest section of the book, 200 pages of character concordance.

The book ends with several short non-fiction pieces by Hillerman, and three of his short stories. There are also several pages of photos, in which he manages to resemble me two or three times.

For a real aficionado of Hillerman’s books this would be indispensable, and for anyone interested in them at all very enjoyable. Breen is an excellent interviewer, obviously thoroughly familiar with Hillerman’s work and with a great appreciation of it.

The Navajo material was interesting, as were Hillerman’s non-fiction pieces — the part of the book most likely to be new to his fans. The Concordance was the least interesting to me, and I think likely to any but his most involved fans. At $25 a throw I’d say it’s best read from the library for all but his most enthusiastic followers, but for them it will be a treasure.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #14, August 1994.

Sat 17 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

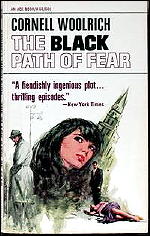

CORNELL WOOLRICH – The Black Path of Fear. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1944. Reprint editions include: Detective Novel Magazine, April 1945; Avon #106, paperback, 1946; Ace H-66, paperback, circa 1968; Ballantine, paperback, 1982.

THE CHASE. United Artists, 1946. Robert Cummings, Michele Morgan, Steve Cochran and Peter Lorre. Screenplay by Philip Yordan, from the novel The Black Path of Fear, by Cornell Woolrich. Directed by Arthur Ripley.

Woolrich at his pulpiest turned in to film noir at its weirdest. Such a treat!

As the book opens, Bill Scott and Eve Roman are just arriving in Havana, fleeing from her husband, gangster Eddie Roman. By the end of the first chapter, she will be dead and he’ll be framed for her murder, which is a lot to pack into one chapter, but Woolrich doesn’t skimp on atmosphere or color as the plot rushes on. He writes about a crowded bar in a way that had me tucking my elbows in, and there’s a very atmospheric chase scene from the fugitive’s POV up a darkened stairway, lit only by the flashlights of his pursuers.

In a typical Woolrichian coincidence, Bill hooks up with a street-smart Cuban Miss named Midnight with a grudge against cops that impels her to help him track down the real killers. And once again we get that superb atmosphere of darkened doorways, twisted streets, and even into the bowels of an opium den, painted in fevered but fast-paced prose. And for a conclusion there’s a knock-down drag-out fight scene, and a bitter, romantic coda Chandler might have envied.

Black Path was filmed in 1946, and before I go into it, perhaps a word about the film’s creators might be helpful:

Producer Seymour Nebenzal was a big name in the early German cinema, with films like M and 3-Penny Opera on his resumé . After he fled Germany to the U.S. his films went into a “cheap-but-interesting†period of things like Hitler’s Madman, but he did produce remakes of his German films Mistress of Atlantis and M.

I have heard passing references to director Arthur Ripley before; UImer referred to him as “a sick man, mentally & physically” and his output was meager, with a few films that had to be finished by other hands. He was apparently a man of ill health and gloomy outlook, who worked most of his early career in comedy for Mack Sennett, Harry Langdon and W.C. Fields (he directed Fields’ classic short Barber Shop.)

After many years as a gag man for Capra and others, Ripley directed Voice in the Wind, The Chase, and part of Siren of Atlantis, then nothing till Robert Mitchum asked him to direct Thunder Road. Damn Strange if you ask me.

Together Nebenzal and Ripley make The Chase something unique, aided by photographer Franz Planer (who sent on to Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T) and a choice cast that includes Steve Cochran as an acquisitive gangster and Peter Lorre as his matter-of-fact executioner, who gripes about sending flowers to the funeral of their late competitor (“A hundred and fifty bucks. I don’t care what you say, that’s inflation.â€)

Narrative-wise, The Chase is something else again. It follows the book pretty faithfully for the first half, then Ripley and writer Philip Yordan apparently decided to leave off and make another movie about the same characters. There’s a scene of shocking surprise, followed by a trite “cheat,†and all at once we’re into a movie where Bob Cummings is a disturbed vet with fits of amnesia.

It’s to the credit of all concerned that this works as well as it does. As I watched, I found myself going from “Aw c’mon!†to “Come on, snap out of it, Bob – and hurry!†as the characters from the first half of the film move toward and away from what looks like predestined fate.

The Chase can’t be called a complete success, but it has its moments, and I guarantee it’s one of the strangest you’ll ever see.

Fri 16 Feb 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

JOHN BUXTON HILTON – Hangman’s Tide. Inspector Simon Kenworthy #3. Macmillan, UK, hardcover, 1975. St. Martin’s, US, hardcover, 1975. Charter/Diamond, paperback, US, August 1990.

It was quite a surprise to see this one out in paperback. Hilton is a fine writer, but it’s always seemed to me that his stories of Inspector Kenworthy of Scotland Yard would be a little too rustic to have much market appeal in this country. Here it is, though, and apparently it’s the first of several.

This particular one takes place in a backwoods marshy corner of England, where a former school administrator has been murdered in gruesome fashion — she’s been hanged to death on a floating scaffold, the platform of which is designed to sink out from under the feet of the victim as the tide comes slowly in.

As usually happens in Hilton’s books, the roots of the crime go far back into the past — indirectly, to a period 300 years earlier, since the murder copies the events of an execution that too place three centuries ago — and directly, a generation of two past, when life may have been simple but certainly wasn’tany easier, as an unhappy woman’s diary clearly shows.

Kenworthy uses a questioning technique that’s often deliberately antagonistic, on the principle that more may be revealed when the answerer is angered than not. He is also deliberately eccentric, known for flouting the rules whenever he sees fit, and invariably equipped with a vivid flair for the dramatic.

The first third of the book is the best. The middle portion sags badly when Kenworthy departs the scene for a short while, leaving the investigation in the stalwart hands of his assistant, Sgt. Wright, while the ending can easily leave the reader with the uneasy feeling of “Is that all there is?” Nonetheless the characters are fleshed out in fine fashion, and in this case, that’s all it takes to make the book worth reading.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File #23, July 1990 (very slightly revised).

Thu 15 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

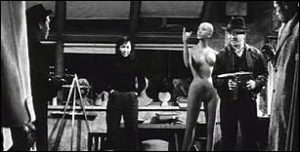

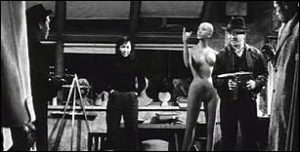

UNDERWORLD BEAUTY. Nikkatsu, Japan, 1958. Original title: Ankokugai no bijo. Michitarô Mizushima, Mari Shiraki, Shinsuke Ashida, Tôru Abe, Hideaki Nitani. Director: Seijun Suzuki.

Sweaty and more than a little bit sleazy, Underworld Beauty borrows liberally from the American gangster genre, film noir, and the juvenile delinquent film, all the while creating something exciting and new, if not completely coherent.

Directed by Seijun Suzuki, this compellingly hip Japanese crime film exudes raw energy and sparkles with punctuations of gunfire. It eventually reveals itself to be an offbeat love story with the dark fatalistic humor of Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956), the sly direction of Sam Fuller, and the aesthetic of a 1950s hot rod exploitation film about rebellious teens and their jazz-infused dance parties.

Filmed in black and white Cinemascope, Underworld Beauty opens with former convict Miyamoto (Michitarô Mizushima) making his way through the dank Tokyo sewers. He’s down there in the muck to retrieve stolen diamonds that he hid away in a wall below the urban streets prior to his incarceration.

The film follows Miyamoto, clad in a black jacket and fedora, as he makes a deal with a yazuka crime boss, tries to make amends with his former partner, and begins a love-hate relationship with the latter’s wild sister Akiko Mihara (Mari Shiraki). Through a twist of circumstance, Miyamoto’s former partner ends up swallowing the diamonds, only to die from falling from a roof.

Akiko’s boyfriend, who works as a designer of mannequins, cuts open the newly deceased and steals the diamonds out of the body. In a whirlwind of cinematic frenzy, the story moves ahead with various deceptions, a double-cross, a kidnapping, and a final dramatic shootout in a steamy furnace room. The acting may be decidedly mediocre, but the energy is infectious.

Thu 15 Feb 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

MARISHA PESSL – Night Film. Random House, hardcover, 2013; trade paperback, 2014.

Mortal fear is as crucial a thing to our lives as love. It cuts to the core of our beings and shows us what we are. Will you step back and cover your eyes? Or will you have the strength to walk to the edge of the precipice and look out?

Night Film dares you to look into that precipice, and both the view and the journey are well worth it.

I’m not easily impressed by so called Meta-fiction. Too often I find the attempt gimmicky and distracting, the writing, characterization, plot, and basics of story-telling lost in a maze of clever ideas that are too much trouble to bother with for the work that it results in.

In the case of Night Film none of that is true.

This one is a stunner, both entertaining and fun, and revealing of deeper matters. I am seriously in awe of and envy of Marisha Pessl’s gifts as a writer.

Dead is Ashley, the daughter of cult film maker Stanislas Cordova (“Everybody has a Cordova story whether they like it or notâ€) whose dark and violent films reflect something sinister about the man himself. It’s ruled a suicide, but investigative journalist Scott McGrath thinks there is more to the death of the troubled young woman than meets the eye and, with his assistants, Nora and Hopper, begins to delve into the personal history of the reclusive Cordova family and their multiple truths, a journey complicated by McGrath’s own secrets — even those hidden from himself.

As plots go, this one predates Citizen Kane, but that is the last mundane thing about this inventive and suspenseful literary thriller that spins out in a dozen directions at once from its premise.

Dazzling is a word that is overused, but this one is just that.

Replete with photographs, reproductions of websites, even a Wi-Fi interactive Night Film Decoder App for your PC or other device that can be used to access secrets and films triggered by a symbol of a bird on many of the photographic pages. This could all be hugely annoying and ultimately pointless, if the book wasn’t so good; it needs none of that to work.

That is all icing on a cake that is a delight unadorned. Suspense novel, thriller, detective puzzle, psychological profile, case study in the outre and the weird, study in film history and theory, Night Film will remind you of nothing so much as Theodore Rozack’s brilliant novel Flicker, but as shockingly new now as that book was then.

The book has everything, including a diabolical curse, and enough twists and turns to give even the most jaded reader of detective novels and thrillers whiplash. Read this one, enjoy it, delight in it. Books this good just don’t come along that often.

Mon 12 Feb 2018

Posted by Steve under

General[11] Comments

I’m posting this from my cell phone. I had the hard drive from my laptop replaced last week which was fine but I’m still trying to get all the associated hardware working in sync again.

I had to take it back to the PC repair shop today since the touchpad was interfering with the mouse, making the cursor jump all over the place. Disabling the touchpad is supposed to be easy. Except on a few select Dell models.

Guess whose model was selected?

No prizes for guessing right.

Sun 11 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

PORT OF SHADOWS. Les Films Osso, France, 1938. Original title: Le quai des brumes. Jean Gabin, Michele Morgan and Michel Simon. Screenplay by Jacques Prevert, from a novel by Pierre Dumarchais. Directed by Marcel Carné.

A dark, poetic film that looks forward to film noir and the later novels of David Goodis.

Jean Gabin, the French Bogart-before-there-was Bogart, plays an army deserter heading for Le Havre, looking to find a ship to flee the country. What he finds are a stray dog that adopts him on the highway into town, and a lot of have-nots willing to share their meager fortunes with him, and discourse Goodis-style on life, love and dreams.

Also hanging around town are a few local hoods in some kind of scrape with a shady store-keeper and his daughter (Michele Morgan, looking more radiant and lovelier here than in any of her American films) and it’s not long before Gabin and his mutt find themselves in the proverbial thick of things as he tries to understand the tangled relationships and get out of town.

I’ll say up front that this thing is awfully contrived; characters turn up in unlikely places with no more reason for being there than to move the plot along. But I’ll also say that Director Carné handles it so gracefully one doesn’t want to notice.

The small-time gangsters are evoked with just the right measure of terse absurdity, their put-on hard-boiled act melting away at Gabin’s genuine toughness, and the winos and poets fill in the background vividly, talking with that awesome redundancy one finds in dark artists like Woolrich, Goodis and Jim Thompson.

The outcome is as pleasingly phony as the rest of it, but I have to say Carné rings in a moving surprise at the very end. The final image of the little dog walking down a highway to nowhere in particular is one that will stay in my mind long after whole other movies are forgotten.

« Previous Page — Next Page »