February 2018

Monthly Archive

Sat 10 Feb 2018

THORP McCLUSKY “The Crawling Horror.” First published in Weird Tales, November 1936. Reprinted in Avon Fantasy Reader #6, 1948, and The Macabre Reader, edited by Donald A. Wollheim (Ace D-353, 1959), among others.

This strange story is told by a farmer to a local doctor who in turn tells it to us. The farmer has rats in his house and barn, but when they begin to disappear, he gives the credit to his several cats. Then the cats start to vanish. Can his dogs be next?

He is sitting in front of his fireplace, reaches down to pet his dog and … I’ll quote:

“It was a slimy sort of stuff, transparent-looking, without any shape to it. It looked as though if you picked it up it would drip right through your fingers. And it was alive — don’t know how I knew that, but I was sure of it even before I looked. It was alive, and a sort of shapeless arm of it lay across the dog’s back, and covered her head. She didn’t move.”

What do you think? What would you do?

PS. Things get worse from here. This is only the beginning.

Sat 10 Feb 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

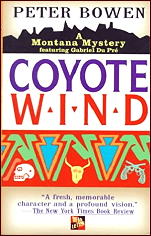

PETER BOWEN – Coyote Wind. Gabriel Du Pré #1. St. Martin’s, hardcover, 1994; paperback, 1996.

Bowen is the author of three books about Yellowstone Kelly. This is his first mystery, and the first of a projected series.

Gabriel Du Pré is a brand inspector in Montana, and a French Indian, a Métis, a descendant of the voyageurs. He’s widowed, with a 14 and a 21-year old daughter, the latter happily married and turning out babies, the former bright and rebellious. He has an ongoing relationship with a 40-year woman with four children whose husband has left her, and he has taste for fiddling and whiskey.

He’s inveigled by the Sheriff into accompanying a cowboy from a ranch owned by a family of rich Eastern drunkards up into the hills to the site of a newly discovered old plane wreck. He finds skeletons there, and a skull with a bullet hole. The plane turns out to have crashed nearly 40 years ago, and the skull to be part of a legendary local unsolved murder. It will turn more lives than one upside down before all the connections are made and all the old ghosts laid to rest.

I liked this a lot. I liked the writing. and I liked the characters. Bowen has a distinctive voice,one which matches narrative and story admirably. Du Pré is one of the more original leads to come along in the last few years, and one of the more appealing. Bowen has a love and a feel for the Montana landscape and way of life that is evident on every page, though it never interferes with the story.

It seems to me a very masculine book, though there are a couple of strong female characters, and I’ll be interested to see if it appeals to women at all. It’s a slender book, but just the right size for the story it has to tell. This is one of the best I’ve read this year.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #14, August 1994 (slightly revised).

Bibliographic Note: Barry was certainly correct about Du Pré becoming a continuing character. There are now fourteen in the series, with Bitter Creek being the most recent one, coming out in 2015.

Thu 8 Feb 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

REX STOUT – Please Pass the Guilt. Nero Wolfe & Archie Goodwin #45. Viking, hardcover, September 1973. Bantam, paperback, October 1974.

When this book was published, Rex Stout was 87, and it had been four years since Death of a Dude, the previous book in the series. I hate to say it, but like many other mystery writers with long careers, the ones written at the ends of their careers are far from their best.

In Stout’s case, I have to confess that I never thought the detective end of things was his strong suit. What I remember about the books is hardly ever the endings, but the setups for the stories and the comfortable feeling of settling down in a familiar milieu and enjoying the personalities of the cast of characters, their idiosyncrasies and habits, the wit and the repartee, all wrapped up in another episode of their long crime-solving careers.

All of the latter is still present, and the case is interesting at the beginning — a bomb goes off in a drawer in a TV executive’s office and kills one of the employees working there. But was the bomb meant for the executive who owned the office, or was it intended for the dead man, and if so, how did the killer know he was going to open that drawer at that particular time?

But there are no witnesses, no clues, and with all of the combined resources that Wolfe has to hand — namely, Archie, Saul, Fred and Orrie — the investigation goes absolutely nowhere. It goes so badly that Archie has to apologize to the reader for it. There is no flow to the story, the rhythm is off, and while I don’t know if this is different from earlier books, but the paragraphs are often unwieldy long, including large chunks of dialogue.

Worse, the solution (to me) comes from almost nowhere, with no motivation for the killer. I am willing to stand corrected on this, but even if I missed something, this is a book that is nowhere near Stout at his prime.

Wed 7 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

MAX BRAND “Werewolf.” Novella. Western Story Magazine, 18 December 1926. Included in Men Beyond the Law (Five Star, hardcover, 1997; Amazon Encore, softcover, 2013). [Thanks to Sai Shankar for coming up with the latter information.]

ALL day the storm had been gathering behind Chimney Mountain and peering around the edges of that giant with a scowling brow, now and again; and all day there had been strainings of the wind and sounds of dim confusion in the upper air, but not until the evening did the storm break. A broad, yellow-cheeked moon was sailing up the eastern sky when ten thousand wild horses of darkness rushed out from behind Mount Chimney and covered the sky with darkness.

You don’t get a much more evocative opening than that for a Western novella called “Werewolf,†and the story lives up to both its title and that opening in ways you won’t expect from Max Brand (who did write some fantastic fiction).

I can honestly say this is the strangest story I have ever read by Brand, and as honestly say it is one of the most satisfying, mixing all those elements of mythology and classical literature with a rousing good adventure story set in the more or less modern West (modern enough for telephones anyway).

On that bitter night Chris Royal (“There were no political parties in Royal County or in Royal Valley, for instance. There were only the Royal partisans and their opponents.â€) walks into Yates Saloon to escape the storm where Cliff Main, gun happy brother of killer Harry Main, is looking for trouble over a girl both like.

Words are exchanged, and there is the smell of cordite in the air.

Cliff Main is dead and Chris Royal alive.

At least until Harry Main comes to avenge his dead brother. Chris doesn’t much fancy his odds against Harry Main. His crossbred hound, Lurcher would have better odds, and Lurcher isn’t much to look at. Being convinced that he’s a coward, like the hound Lurcher, who isn’t much good but is loyal to Chris and loved by him, and that he has no chance against Main, Chris hightails it for the high country.

Which is where this story turns decidedly weird.

Because something is trailing Chris, and it isn’t Harry Main … “it was no animal of flesh and blood at all, but a phantom sent to cross his way with a foreboding of doom.â€

He’s not far off.

An old Indian Chris meets fishing in the river sets the philosophical tone of the tale. He warns Chris that no man can escape his fate, and when they hear the wolf that had trailed Chris the night before he explains it is a werewolf:

“There are two kinds of werewolves,” said the chief, holding up two fingers of his hand. “The first are the ones which have been men and become wolves. They are only terrible for a short time, and then they become stupid. Then there are others. They are the wolves that cannot become men until they have killed the warrior who has been marked out for them.”

That old Indian is more than a convenient literary device, I warn you.

Chris masters his fear after that and returns home to face Harry Main, his preternatural calm in the face of almost certain death almost unnerving the mankiller, but even with Main out of the picture there remains that second kind of werewolf, the one that cannot become a man again until it has killed the warrior marked for it, and in that game a worthless cowardly dog named Lurcher get a chance to redeem himself as his master has.

It is an odd duck of a story by any measure, part Western revenge story, part tale of redemption of man and dog, part dog story, and part … well you decide, but I will reveal this much, werewolf in this story is both a metaphor and not a metaphor.

If you ever wondered what Max Brand might have written for Weird Tales, this is the story.

Tue 6 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

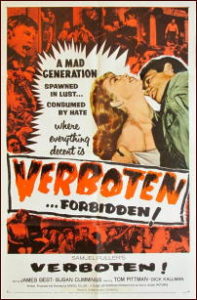

VERBOTEN! RKO Radio Pictures, 1958/Columbia Pictures, 1959. James Best, Susan Cummings, Tom Pittman, Paul Dubov. Screenwriter-director: Samuel Fuller.

Highly uneven and overly didactic, Samuel Fuller’s Verboten! is a quirky, stagey film about an American GI in Occupied Germany at the end of the Second World War. After he loses two of his colleagues and he himself gets injured in combat, Sergeant David Brent (James Best) finds himself the houseguest of an anti-Nazi German girl (Susan Cummings) who nurses him back to health. To no one’s surprise — certainly not to this viewer — Brent falls in love with his German companion. But since marriage and fraternization between the two is forbidden — verboten! — Brent decides to leave the Army and to serve in the civilian occupation of Germany.

Little does he know that his wife’s friend Bruno Eckhart (Tom Pittman) and her younger brother are both secretly working with the Werwolf, the underground pro-Nazi “resistance.†Much of the movie is filled with heavy-handed dialogue about the difference between ordinary Germans and Nazis and the ways in which Hitler manipulated the German people into following him.

Some of this is effective; a lot of it is over the top and actually serves to take away from the potency of the subject manner. There is, however, a stunningly effective sequence in which Eckhart attempts to rally a coterie of young, angry men to the Nazi cause in the rubble of occupied Germany. Pittman, who was a compelling screen presence, tragically died in a car crash in late 1958 at the young age of 26 several months before Verboten! was released in theaters.

Fuller, always a maverick, utilizes Beethoven when showing the Americans in combat and Wagner for the Germans. That aesthetic choice, along with the choice to insert highly graphic newsreel footage from the concentration camps in the film, has the unusual effect of giving the entire movie a semi-documentary feel in which fiction and fact are intertwined in a decidedly ambitious, but ultimately mediocre war film. Verboten! is a movie wants to say a lot, to shout it from the rooftops, but does so in such a frenetic manner that the message gets drowned out by its own unfortunate shrillness.

Sun 4 Feb 2018

I’ve asked Ian Dickerson, the author of the following book to tell us more about it. He’s most graciously agreed:

IAN DICKERSON – Who Is The Falcon?: The Detective In Print, Movies, Radio and TV. Purview Press. softcover, December 2016.

Back in the dim and distant past, when I was just a lad, I discovered the adventures of the Saint. (I know, I know, I’ve kept that quiet….) In those heady days I was a sucker for any new Saint-like adventure so when the BBC ran out of old black and white Saint films to show and moved onto something called ‘The Falcon.’ my place in front of the television was assured for a few more weeks.

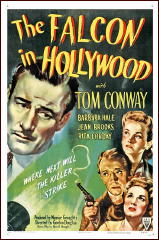

Those early Falcon films were remarkably Saintly, and although the later ones got a little more creative — The Falcon and the Co-Eds anyone? — they were still firmly in the gentleman detective genre and my teen -aged self was happy.

Fast forward a few years — well, okay, quite a few years — and I discovered old time radio shows. But I soon had a problem, I had all the episodes of The Saint on tape and being greedy I wanted more. Then I discovered the Falcon had also appeared on radio! Aha, problem solved I thought! But when I listened to the tapes I discovered the Falcon — that radio Falcon — was a hard boiled 1940s PI and bore virtually no resemblance to the gentleman detective of the George Sanders and Tom Conway films. At a time when the Internet was only really just booting up, I had no way of establishing what had happened, but I rather enjoyed those hard-boiled PI adventures so quickly ordered some more.

Fast forward a few more years and with the help of the now mature Internet, I discovered that not only had the Falcon also appeared in books, magazines and on TV, but that the radio show had run for over a decade and there had been over four hundred and eighty episodes.

I wanted to learn things; to find out why there were two different characters and how they’d come to be changed, to find out more about the Falcon’s TV adventures and see if I could find copies of them, I also wanted to know more about his stint on radio — who played him? Who wrote the stories? What were they about? And for the geek in me … had I listened to all the ones that were available? (I certainly have now!)

And I wanted to celebrate a character that had survived sixteen films, a handful of books, thirty-nine episodes of television and that long run on radio.

So I wrote a book.

Who is the Falcon? tells the story of all the Falcon’s adventures in print, on radio, in film and television. And there’s even a Falcon short story from the 1940s thrown in for good measure.

Sat 3 Feb 2018

CORNELL WOOLRICH “Vampire’s Honeymoon.” Lead story in the collection Vampire’s Honeymoon, Carroll & Graf, paperback original, 1985. First published in Horror Stories, August-September 1939.

First of all, there’s a reason why this story wasn’t reprinted until the C&G paperback collection came along, almost 50 years after its first appearance in a what’s called a weird menace or “shudder pulp.” It really isn’t very good.

The title tells it all, or nearly so. A man, a well-educated fellow, goes to a party engaged to one girl, and leaves with another — a beautiful woman who he meets on a fourth-floor terrace as she seems about to jump — or float? — off. No one knows who she is, nor did anyone see her enter.

They are engaged the next day and are soon married. The husband, as it turns out, is not the brightest bulb in the box. He cannot figure out why is suddenly afflicted with anemia, with small bites in his neck. Large mosquitoes, he tells the doctor. We the reader know better.

All of the standard tropes about vampires are part and parcel of this tale: his new wife cannot be seen in mirrors, she stays inside in bed all day, is immune to bullets, and I’m sure I’m not giving anything away by telling you that a wooden stake is part of how the story ends.

The story isn’t totally simplistic — Woolrich was too good a writer for that to be true — but it only hints at creepiness and once read, I doubt that anyone will remember it more than a day later. The other stories in the collection, all fairly long, may be better, and you may find me talking about them on this blog as time goes on.

For the record, though, in case I don’t, their titles are “Graves for the Living,” “I’m Dangerous Tonight,” and “The Street of Jungle Death.” I may be mistaken, but I don’t believe that any of these are vampire stories.

Fri 2 Feb 2018

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

The timing couldn’t have been worse. If I had learned of his death a few weeks sooner I would have made him the subject of last month’s column, which was centered on the year 1930. The year he was born.

Donald A. Yates’ birthplace was Ayer, Massachusetts. In 1936 his family moved to Michigan and he spent his formative years in Ann Arbor, where in his teens he met and became close friends with local detective novelist H. C. Branson, to whom someday I must devote a column. He entered the University of Michigan in 1947, choosing pre-law as his major because he “had consumed dozens of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels and was entranced by the prospect of becoming myself a crackerjack courtroom lawyer.â€

But after finding one of his courses “so cut and dried, dusty and lacking in drama and emotion†and learning that most of the courses he’d need to take were of the same ilk, he switched his major to Spanish and graduated in 1951. After two years in the Army he returned to academia and earned his M.A. and Ph.D., the subject of his doctoral dissertation being Argentine detective fiction. He joined the Michigan State faculty in 1956 and remained a professor until 1982 when he took early retirement.

I first met Don in the late 1960s when he was teaching Spanish and Latin American literature at Michigan State and I was fresh out of law school. He had been a professor for more than ten years and had made a name for himself as a translator of the now internationally renowned Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), who was little known outside his native Argentina until the early 1960s.

Like Poe, Borges wrote all sorts of literary works: poetry, essays, fantasies, and some landmark detective-crime stories that were like no others ever written before or since. It was one of these, “The Garden of Forking Paths,†translated by Anthony Boucher and published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (August 1948), which first introduced Borges to a wide English-language audience.

But he remained relatively obscure until a few years after Don had begun his career at Michigan State. He had become interested in Borges while studying for his doctorate, and LABYRINTHS (New Directions, 1962), edited by Don and another young professor named James E. Irby, was one of the first collections of the Argentine’s work to appear in English, published almost simultaneously with FICCIONES (Grove Press, 1962), with which Don was not connected.

Together the two volumes established Borges’ reputation as a titan of international literature. Among the now classic crime stories collected in LABYRINTHS with Don serving as translator were “The Garden of Forking Paths†(why Boucher’s translation wasn’t used remains a mystery) and “Emma Zunz,†which today has been rendered politically incorrect almost to the point of unrevivability by time, feminism and the Holocaust.

Don’s LABYRINTHS translation of another now world-famous Borges detective story, “Death and the Compass,†originally appeared in the Mystery Writers of America anthology TALES FOR A RAINY NIGHT, edited by David Alexander (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1961). Fred Dannay was offered the translation first but, for reasons that remain unclear, turned it down.

Don was under the impression that Fred thought it “too far above the heads of the magazine’s readers†but, unless my aging memory has deceived me, Fred told me that the Borges story, which had first been translated several years before, had struck him as too similar to the plot of the Queen novel THE PLAYER ON THE OTHER SIDE, which he was either working on at the time or had recently completed. “Death and the Compass†appeared in EQMM for August 2008, long after Fred’s death.

During the decades following the Sixties, Don’s translations of various Latin American crime stories appeared in EQMM and elsewhere. Among the authors whose appearances in English were to his credit are Augusto Mario Delfino, Marco Denevi, Alfonso Ferrari Amores, Antonio Hel_, Maria de Montserrat, Manuel Peyrou, Hernando Tell_z and Rodolfo J. Walsh.

In the early 1970s the Catholic religious publisher Herder & Herder was bought by McGraw-Hill and expanded into several new areas. It was for Herder that Don edited LATIN BLOOD (1972), an anthology of mystery tales from Central and South America, which includes three stories by Borges: the by now much reprinted masterpieces “The Garden of Forking Paths†and “Death and the Compass†plus the unfamiliar, rousingly Chestertonian “The Twelve Figures of the World†(co-authored by Borges’ longtime friend Adolfo Bioy Casares).

Don also translated for the same publisher Manuel Peyrou’s THUNDER OF THE ROSES (1972), a murky and labyrinthine political thriller with detective overtones, set in an imagined variant of the Third Reich and heavily indebted for its plot elements to Borges. The morning after dictator Cuno Gesenius has been murdered, a tormented intellectual named Felix Greitz publicly assassinates Gesenius’ double. Did Greitz think he was killing Gesenius? Was he trying to protect his own wife, a member of the anti-Gesenius underground who disappeared shortly before the dictator’s death? Did he kill Gesenius and then shoot the double to convince the authorities he didn’t know the dictator was already dead?

Police inspector Hans Buhle saves Greitz from execution on condition that he work inside the underground to expose Gesenius’ murderer. Whether he or Buhle or we ever find out or are meant to find out the truth is debatable. That seems to be the purpose of Peyrou’s Borgesian labyrinth: to make us perpetually uncertain.

In his introduction Borges compared Peyrou with Dostoevski and praised the novel’s “shrewd interrogations and treacherous dialogues; the spheres of the search and of what is sought are interwoven and become confused. We experience the melancholy that is the attribute of any dictatorship, the systematic oppression of stupidity, but also mockery and courage. I do not hesitate to declare that Manuel Peyrou is one of the first storytellers of Hispanic letters.â€

In 1969, when Borges was in the States on a lecture tour, Don invited me to have lunch with the great Argentine and his then wife. Knowing very little about Borges at that early stage of my life and my relationship with Don, I can recall nothing of what we said over the meal. I do remember that while we were eating a man with a camera came to our table and requested permission to take a picture. Borges agreed. The man told him to say Cheese. “Might I say Chesterton instead?†Borges asked. As I hinted above, GKC was always one of his favorites.

Over the decades Don wrote several detective short stories of his own. One of his earliest, written during his time in the military, was “The Wounded Tyrolean,†which was based on a cryptic reference in Ellery Queen’s THE SPANISH CAPE MYSTERY (1935) to a case the great sleuth was unable to solve. The tale, which has no connection with EQ except that its title comes from an allusion in a Queen novel, wasn’t published until well over half a century later when it appeared in the Fall 2012 Michigan Quarterly Review.

Don’s earliest published story that I’m aware of is “Inspector’s Lunch,†which appeared in something called the Birmingham Town Hall Magazine back in 1955 and was reprinted in The Saint Mystery Magazine for May 1959; the most recent (except for the Wounded Tyrolean tale) is the Sherlockian “A Study in Scarlatti†(EQMM, February 2011).

Don was an enthusiastic Baker Street Irregular, being invested as “Mr. Melas†(The Greek Interpreter) back in 1960 and founding a Napa Valley branch of the Irregulars after he retired from Michigan State and moved to California’s wine country. Well into his final years he’d fly into New York for the annual BSI dinner whenever his failing health permitted.

As the Wounded Tyrolean anecdote suggests, Don was a devotee of Ellery Queen from an early age. When he was 16 he took a bus from Massachusetts to Manhattan and visited with Ellery’s co-creator Fred Dannay, the beginning of a friendship that lasted until 1982 when Fred died. In 1979, during an elaborate dinner at New York’s Lotos Club celebrating the 50th anniversary of the publication of the first Queen novel, THE ROMAN HAT MYSTERY, Don paid two heartfelt tributes to EQ. One was what he called an acrostic sonnet, with the first letters of each of the fourteen lines spelling out the name FREDERIC DANNAY. The second, on a more lighthearted note, was a song to be sung to the tune of the Mickey Mouse Club theme, with the last line, where Mickey’s name is spelled out, being replaced with E-L-L-E-R-Y Q-U-E-E-N. Both Fred and I heard Don sing that song. I wish I had a copy.

For most of the world the great author with whom Don was associated was Borges, but personally I was more interested in another writer with an international reputation: Cornell Woolrich, the Hitchcock of the written word. Don first met Woolrich at the Mystery Writers of America awards dinner in 1961. What followed, Don wrote, was “a long and glorious evening, the first of many…that I would spend doing the nightspots with him, with this lonely writer who would never let you say goodbye until daylight was in the street.â€

On his frequent trips from East Lansing to South America and back on various Fulbright grants Don often stopped off in Manhattan and spent time with Woolrich, getting to know that haunted recluse as well as he allowed himself to be known. Woolrich died in September 1968, and I believe it was on the visit the following year during which Don introduced me to Borges that he read to me from a memoir he had written about the master of suspense. Many years later I included excerpts from it with his permission in my Woolrich book FIRST YOU DREAM, THEN YOU DIE (1988). The final version of his memoir can be found in THE BIG BOOK OF NOIR, edited by Ed Gorman, Lee Server and Martin H. Greenberg (Carroll & Graf, 1998).

He died at his home in St. Helena on October 17, 2017, with his wife Joanne and their beloved dogs at his side. The cause was aplastic anemia, a condition which develops as a result of bone marrow damage. As most readers will remember, October was the time when the Napa Valley wine country was plagued by wildfires. I became concerned about Don and called him. His house was still intact, he told me, but he and Joanne had packed their bags and, with their dogs, were ready to leave on a moment’s notice.

I never heard from him again. It must have been soon after our conversation that he died. In his final years he was working on a memoir of Borges which, so Joanne tells me, remains unfinished. If she can turn the raw material into a book, it will be a tribute to one of the most fascinating people I knew during much of my adult lifetime. And to another fascinating man I only met once.

Thu 1 Feb 2018

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

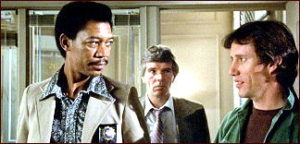

EYEWITNESS. 20th Century Fox, 1981. Also released as The Janitor. William Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, Christopher Plummer, James Woods, Steven Hill, Morgan Freeman. Director: Peter Yates.

In order to appreciate Eyewitness, aka The Janitor, you need to suspend your disbelief. And then do it again. And yet again. Because there are far too many implausible aspects to this Peter Yates-directed thriller to make it anything other than a mere curiosity.

As in the sense of: how did the filmmakers think that many audiences were going to react to the unlikely romance between a janitor who lives with his vicious attack dog in a small untidy apartment and a wealthy, New York society news anchorwoman? And did they really think that Christopher Plummer was the best actor to portray an Israeli agent – one, I should add, who can’t seem to hold his own against a janitor?

Then there’s the plot. (Spoilers Ahead!) Daryll Deever (William Hurt) and his best friend Aldo (James Woods) are Vietnam veterans working as janitors in New York City. Their boss is a Vietnamese guy who was on the opposite side during the war. When he gets murdered, Darryl pretends he knows more about the crime than he really does so he can get close to TV journalist Tony Sokolow (Sigourney Weaver), who is investigating the story.

What charms her most is when he tells her he’s been her greatest fan for years and is consumed with her and how much he loves her. She’s so taken by this obsessive janitor that she’s ready to leave her urbane Israeli fiancé Joseph (Plummer) who, to everyone’s surprise – or not, is an Israeli secret agent. Lo and behold, it turns out that Joseph is the one who murdered Darryl’s boss. You see, until then everyone thought it had to be Aldo because he hates Asian people so much. That’s why he lives in Chinatown, of course.

Roger Ebert liked this movie a lot more than I did, arguing that all of the things that I found absurd to be indicative of the film’s playing with audience expectations. There’s nothing wrong with playing with expectations, of course. But I don’t think that’s what’s going on here. I think it’s more of a case of a horribly miscast film and a romance at the heart of it that really doesn’t pass the laugh test.

Indeed, the best line in the whole film is when Aldo screams at Darryl saying that this whole romance is absurd because Darryl is just a janitor. If that was in the script, then I’ll give the screenwriter and director credit for some self-awareness. But part of me thinks it was Woods, at his unhinged best, ad-libbing. Final note: look for Steven Hill and Morgan Freeman portraying a pair of world-weary cops working the case. As much as I didn’t care for Eyewitness, I’d watch a movie with these two any day.

« Previous Page