Sat 19 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Glass Key.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Pulp Fiction , Reviews[5] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins:

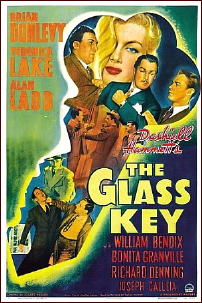

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Glass Key. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1931. Serialized in Black Mask magazine: “The Glass Key” (March 1930). “The Cyclone Shot” (April 1930), “Dagger Point” (May 1930), “The Shattered Key” (June 1930). Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including Pocket #211, pb, 1943 ; Dell 2915, pb, 1966. Film: Paramount, 1935, with George Raft. Also: Paramount, 1942, with Alan Ladd, Brian Donlevy, Veronica Lake.

Hammett’s fourth novel is set in a nameless city modeled on Baltimore, where he grew up. Like Personville in Red Harvest, the city is controlled by crooked politicians in league with various mobster factions; but in The Glass Key Hammett gives us an insider’s view of the corruption and in fact creates a corrupt political henchman as his protagonist.

Ned Beaumont — tall, thin, a dandy and a compulsive gambler and tuberculosis victim like Hammett himself — is the best friend and most trusted adviser of Paul Madvig, the lower-class ethnic who controls the city.

Against Beaumont’s advice, Madvig has made a deal for mutual political support with upper-crust Senator Henry, hoping that the payoff for him will include Henry’s lovely daughter, Janet, with whom he’s infatuated.

Then Senator Henry’s son is murdered in circumstances that implicate Madvig. As Madvig’s enemies plot to speed the politically wounded leader’s fall from power, Beaumont sets out to clear his friend and patron, limit the damage to his machine, and keep the other side’s crooked candidates from defeating Madvig’s crooked candidates in the upcoming election.

In the process he endures perhaps the most savage beating in crime fiction, and the equally painful experience of becoming involved himself with Janet Henry, his best friend’s woman.

The Glass Key is one of Hammett’ s most powerful novels but also one of crime literature’s most frustrating classics. Its third-person narrative voice, like that of The Maltese Falcon, is so objectively realistic and passionlessly impersonal that it seems to draw an impenetrable shield between characters and reader.

As a result, generations of critics have debated all sorts of factual questions that writers less bold than Hammett would have answered unequivocally.

Did Ned really intend to sell Madvig out to his rival Shad O’Rory, or is he playing double agent?

For what earthly reasons did he permit Jeff, O’Rory’ s unforgettable moronic bone-crusher, to beat him almost to death? Is he really in love with Janet Henry or does he have a suppressed homosexual desire for Madvig?

Reading the novel again and again only fuels these controversies, for Hammett refuses on principle to enter into any of his characters’ thoughts and feelings, and forces us to judge from what they say and do — from inherently misleading and uncertain data. No wonder there’s no consensus about The Glass Key!

Hammett himself, and such experts as Julian Symons and Frederic Dannay (Ellery Queen), thought it was his best novel; a number of academic literary critics rank it as his worst.

Hammett’s vision was one of the darkest in the history of crime fiction. He saw the world as an incomprehensible place in which no one can ever really know another, and created the world of The Glass Key to match.

Whatever the ultimate verdict on its literary status, it’s a compulsively readable, coolly sardonic portrait of an unredeemable nightworld and ambiguous relationships, and stands beside The Maltese Falcon as one of the earliest classics of noir crime fiction.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

September 19th, 2009 at 9:39 pm

Dorothy Parker can be counted among those who thought this was Hammett’s best book. I put it a little behind Falcon, but still count it high among his works, and for me many of the unanswered questions only add to the books value.

The book is the closest to a novel as opposed to mystery novel that Hammett wrote. Those questions that readers are still asking may haunt us, but they keep us turning back to the book the way you usually only turn back to classics of literature, not detective stories.

I’ve seen both films, though the print of the first wasn’t that great. The second version with Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake and that great screenplay by Jonathan Latimer deserves to be a classic. William Bendix is unforgettable as Jeff (Guinn ‘Big Boy’ Williams wasn’t bad in the first version). There is also a fair version done on live television that used to be available on VHS though it has one of those memorable live scenes when the corpse leaves the scene too soon. Beaumont’s escape from Jeff is done fairly well for a live scene.

September 19th, 2009 at 10:25 pm

David

The live TV production you mention, could that be STUDIO ONE, 11 May 1949?

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0712469/

— Steve

September 19th, 2009 at 10:40 pm

Steve

I think that is the one. Have to dig around to find the tape and be sure. All things considered it wasn’t a bad little film. It was one of a handful of old television shows released by Video Yesteryear.

David

September 6th, 2011 at 5:31 pm

Can anyone get copies of the Black Mask magazine with the Glass Key, (story), just the illustrations would be worth it.

April 15th, 2020 at 9:22 am

[…] Glass Key has been reviewed, among others, at Mystery*File (Curt J. Evans); and Mystery*File (Francis M. […]