Tue 3 Apr 2012

by Josef Hoffmann

If we were to believe the language of publishers, booksellers and collectors, there is a multitude of so-called “crime classics.†And yet not every crime novel that has exercised a certain appeal on a particular number of readers, even decades after its publication, deserves the attribute “crime classic.â€

At a time of “retromania†(Simon Reynolds), at a time in which computers, the internet and e-books can and perhaps will tend to compile, store and make accessible all texts, longevity in itself is not sufficient as a criterion.

The term “crime classic†denotes a distinction, a seal of quality, which raises the novel concerned above the average, especially when books are produced and distributed more or less industrially in masses. So which crime novels have the prerogative to maintain a presence and to claim the attention of generations of readers?

If we try to determine the particular characteristics of a crime classic, we might concentrate on the intrinsic qualities of the narrative text, such as an ingenious plot and lustrous prose, or on extrinsic features such as its continuous presence in the book market over decades and special regard among literary critics.

At any rate, “classic†in the sense of a crime novel does not mean that it corresponds to the literary-aesthetic ideals of a so-called classic era, that it distinguishes itself from romantic or realistic or other epochal styles, or that it demonstrates a particularly exquisite language.

Classic is also not identical to nostalgic. That said, any nostalgic reading need, satisfied by a certain crime novel that revives good old or bad old times, does not necessarily mean that the novel is not a crime classic.

It seems obvious to assume a complex interplay of the intrinsic and extrinsic qualities of a crime novel, which ultimately lead a particular crime novel to stand the test of time, to still appear “fresh†even after decades have passed, and to enrich its reader.

I now intend to examine more closely how such interplay works, creating tradition and literary history.

While Edmund Wilson’s infamous polemic “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?†might be arrogant, it does provide an opportunity to undertake certain differentiations. A distinction must first be made between “crime classics†and the classics of world literature.

“Crime classics†are not classics that also happen to be crime novels. “Crime classics†require other criteria of attribution. If we were to apply Wilson’s standards of modern classic literature (James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann), there would be at most a dozen crime novels that would meet these standards and deserve the title of “classic.â€

Using Gertrude Stein’s criteria for “masterpieces†would produce even fewer. In her view, masterpieces do not describe the things of reality, recognised by the reader to his enjoyment; rather, they create and embody a being in themselves, something fundamentally new. This is the case in very few crime novels, if at all in any.

Furthermore it should be noted that a “crime classic†is not automatically every work by any crime author who has also written, among other things, a few “crime classics.†If, for example, we consider the best, most successful crime novels by Agatha Christie to be “crime classicsâ€, this does not mean that her weaker publications should also achieve this status.

Crime authors are rarely so perfect, from a literary point of view, to suggest that those who have written a number of “crime classics†will never dip below this level, and always write masterfully. Such an assumption is disproved by many weak crime novels by good authors.

Ultimately, the criteria for all subgenres of crime novels are not the same. Different standards apply to the traditional whodunit, which make the novel a “crime classic,†than to a gangster story or a psycho thriller.

In a whodunit much more emphasis is placed on a perfectly structured, thoroughly logical and at the same time original plot, on the clever distribution of “clues†throughout the text and a surprising and plausible solution to the riddle than is the case in a gangster story.

What is required of all “crime classics,†however, is that they demonstrate a certain superior level of prose, and that their specific dramatic suspense works.

One criterion that is insufficient to qualify a novel as a “crime classic†is some random innovation; e.g., a particular method of murder or a criminal deduction technique, which is presented in a novel for the very first time. In spite of the innovative element a crime novel might still be written using lousy language and a sloppy plot, so that the predicate “crime classic†is not appropriate.

Equally insufficient is the fact that a crime writer (or his works) was read widely at the time and showered with praise by critics. I question, therefore, whether even a single work by Edgar Wallace deserves to be considered a “crime classic†although he was appreciated by highly competent authors such as Gertrude Stein, Dashiell Hammett and H. R. F. Keating.

Positive acknowledgement by literary critics is an extrinsic feature. A prerequisite here is continuity over a long period of time, which does not mean that all criticism highlights the same aspects of a crime classic and appraises them positively. Perspective and standards can shift, particularly over the course of decades.

Not every critic must provide identical reasons for his praise. A further extrinsic characteristic of a crime classic is that it is generally read more than once. Especially in the case of the traditional whodunit a large time span is often left between readings, so that the forgetful reader can try to solve the mystery anew.

But we should remember Chandler’s criterion that a really good crime novel must also provide reading pleasure even if the last chapter is missing (and even if the experienced reader figures out the end of the story).

In other words, every crime classic must possess literary qualities and may not profit merely from the uncertainty as to how the story ends. It must touch the reader, so that scenes, lines of dialogue, comparisons or other elements of the novel become indelible in his memory. It may not leave one cold, but instead must challenge the reader to adopt a position for or against the crime novel or some of the statements contained therein.

More specifically, a crime classic must distinguish itself by means of such a complex power of literary qualities that a single reading, or a reading in a particular historical period, does not exhaust these literary riches, but rather the work provides new aspects for later readings or subsequent generations of readers.

Upon first perusal in youth, the aspects that play a role and are assessed positively will be different to those in more mature years, or in later life. The manner in which this is caused by a crime novel might well remain a mystery to most readers, upon which critics and literary scholars can continue to work. I only wish to warn against awarding the distinction of crime classic prematurely to all old crime novels that appear, in some way, to be worth reading.

To conclude, here are some suggestions related to the discussion: Are the following crime novels crime classics or simply cult novels for those in the know?

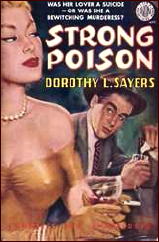

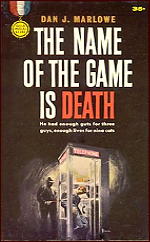

Dan J. Marlowe: The Name of the Game Is Death (1962), praised by Ed Gorman, Stephen King.

Ted Lewis: Jack’s Return Home (1970), praised by Paul Duncan, Max Décharné.

Simon Troy: Waiting for Oliver (1963), praised by Mary Ann Grochowski, Bill Pronzini.

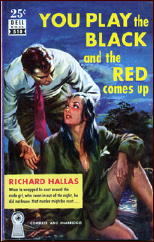

Richard Hallas: You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up (1938), praised by David Feinberg, E. R. Hagemann.

Vin Packer: Whisper His Sin (1954), praised by Anthony Boucher, Jon L. Breen.

Mildred Davis: The Room Upstairs (1948), praised by Marvin Lachman, Jean-Patrick Manchette.

Norbert Davis: The Mouse in the Mountain (1943), praised by Bill Pronzini, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

James Reasoner: Texas Wind (1980), praised by Ed Gorman, Bill Pronzini.

Sources:

Italo Calvino: Warum Klassiker lesen?, Munich/Vienna 2003 (English edition: Why Read the Classics, in: The Uses of Literature, 1986)

Raymond Chandler: Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner & Kathrine Sorley Walker, London 1962

J. M. Coetzee: Was ist ein Klassiker?, Frankfurt am Main 2006 (English edition: What Is a Classic?: A Lecture, in: Stranger Shores. Literary Essays 1986-1999, New York 2001)

T. S. Eliot: Was ist ein Klassiker?, in: Ausgewählte Essays, Berlin/Frankfurt am Main 1950, 469-511 (English edition: What Is a Classic?, London 1945)

H. R. F. Keating: Crime and Mystery: the 100 Best Books, London 1987

Ezra Pound: ABC des Lesens, Frankfurt am Main 1967 (English edition: ABC of Reading, New York 1934)

Gertrude Stein: Was sind Meisterwerke. Essay, Zürich 1985 (English edition: What Are Masterpieces and Why Are There So Few of Them?, 1940)

Edmund Wilson: Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?, in: Howard Haycraft (ed.): The Art of the Mystery Story, New York 1992, 390-397

Translated by Carolyn Kelly.

April 3rd, 2012 at 6:16 pm

The first thing I should say is that the choice of cover images to go with Josef’s article was mine and not his.

I am assuming that most mystery readers will go along with my choices as being crime classics, but if the consensus is that I’m wrong, I can easily replace any ringer with another better choice.

It isn’t as though I ran out of books to choose from.

As far as the list of possible cult classics, Josef, you left us with, I’d have to say that that’s the most you could say of them, that they are “cult classics” only.

They are neither widely enough known or even available, in my opinion, to be true crime classics. (One or two of them I am, I confess, only vaguely aware of.) But the term “cult classics” fits them well.

At least two of them have been reviewed on this blog. The others ought to be.

April 3rd, 2012 at 6:58 pm

I am still confused about what you define as a crime classic. You mentioned a great deal about what isn’t, to the point I am not sure any fiction could be considered a classic.

My definition of a classic is any work appreciated, admired and remembered over many generations.

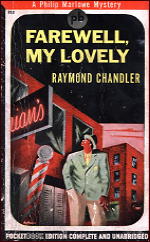

Of all the books mentioned and pictured, I would call only two as classics, MURDER OF ROGER ACKROYD by Agatha Christie and FAREWELL, MY LOVELY by Raymond Chandler.

I am a huge fan of Norbert Davis but find his best work was SALLY’S IN THE ALLEY.

I am not even sure these books are cult classics. Jim Thompson is the best example I can think of at the moment as a cult writer.

Cult classics are work with an intense following that lasts generations. Not books a few critics liked.

April 3rd, 2012 at 7:01 pm

Steve, did you just add the picture of crime classic HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES by Sir Conan Doyle?

April 3rd, 2012 at 7:04 pm

Yes. I had it ready and forgot to include it until I saw the post online.

We’ll add that one to your list of classics.

April 3rd, 2012 at 7:07 pm

Michael, referring to your Comment #2, perhaps I should let Josef reply, but I think he describes what his idea of what a crime classic is in the two paragraphs toward the end that begin with:

“In other words, every crime classic must possess literary qualities and may not profit merely from the uncertainty as to how the story ends…”

and goes on from there.

Your definition is concise and to the point, however:

“My definition of a classic is any work appreciated, admired and remembered over many generations.”

Nothing for me to disagree with there!

April 4th, 2012 at 6:43 am

For me a true crime classic is Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, but also Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me. Both crime novels were groundbreaking, both were translated in other languages, both have been appreciated by many readers and a lot of critics, both provoke a statement for or against it. The role of critics and literary experts seems to be important because to be a classic is not the same as to be popular. Is Homer’s Ulysses still popular?

April 4th, 2012 at 7:29 am

I have to correct my last question. The character Ulysses is still popular, but I doubt if the epic itself, the Odyssey has still many readers. Nevertheless it is a classic.

April 4th, 2012 at 8:27 am

Very interesting. I like your distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic criteria, since it helps point up the sometimes ambiguous nature of the term “classic.”

However, I don’t think that “every crime classic must possess literary qualities,” if by literary qualities you mean what would count in “literary” circles as good writing. My favorite Golden Age writer, John Dickson Carr, is the perfect test case. Can any of his novels really be said to possess literary qualities, other than brilliant plotting and (often) strong pacing? But plot and pacing are surely not what’s meant by literary qualities here. You write, “[the book] must touch the reader, so that scenes, lines of dialogue, comparisons or other elements of the novel become indelible in his memory.” Nothing in Carr touches me this way, except for the unintentionally comic ineptitude of his characterizations. Nonetheless, to say that The Crooked Hinge or The Three Coffins or The Judas Window or He Who Whispers are not classic detective stories is absurd.

April 4th, 2012 at 9:47 am

What makes a classic is an interesting question. Four people have posted comments and we have three different definitions of the word.

#8. John, I don’t consider anything Carr or even Queen wrote to be a classic since they are no longer appreciated by the current generation. I do consider Carr and Queen vital and important authors for their impact on the genre of fiction and literature itself.

Josef, a long time ago I had a discussion in the comments with the long missed David Vineyard about the role of critics. He believed the critic’s role is to decide what is good and what is not. My belief as a former professional critic is the job of the critic is to describe and inform the reader what to expect from the book (or whatever) so the reader can decide for him or herself if they would enjoy reading it. The idea a critic can judge the worthiness of any form of art or fiction better than the unwashed masses of readers is overrated.

You mentioned Hammett’s MALTESE FALCON. I agree it is a classic that people are still reading today and enjoying. It more than any other book represents what the PI is in literature.

Is Hammett’s THIN MAN a classic? It began a popular genre, the romantic mystery. I don’t consider the book a classic, but I do consider the movie a classic, because today more remember the movie than the book.

April 4th, 2012 at 10:15 am

“I don’t consider anything Carr or even Queen wrote to be a classic since they are no longer appreciated by the current generation.”

Unfortunately I have to agree with the second part of your statement. On the other hand, I believe there are works by both authors which at one time were considered classics. If this is so, then the agreement of which books are considered classics and which are not is always in a state of flux, not so? I find the idea both acceptable and dissatisfying.

Another question. The most recent books mentioned so far are ones written by Jim Thompson. Michael, like you, I think he’s more of a cult classic author, but we can leave that discussion for another time. How old must a book be before it’s considered a classic? Several generations, I would agree, but does that allow for books from the 60s? The 70s? Or have books from those eras not yet withstood the test of time?

April 4th, 2012 at 10:20 am

I also wish David Vineyard were here to contribute to this discussion. It has been a year since this month since he last left a comment. He had several physical and other health problems, I know, but every day I look for one of his argumentative, informative and invariably cheerful comments in my inbox.

April 4th, 2012 at 10:30 am

It would be interesting to have someone write a similar study of those detective novels and crime fiction works that are considered the tour de force of a particular author. Does this automatically make them a “crime classic?”

All this labeling is extremely subjective I think. A noir lover will have a list of crime classics that will be completely different from a detective fiction reader who devours impossible crime plots. I know my criteria are very different and I agree with J. Morris that the literary aspects of a crime novel are not that important when it comes to classifying it a classic. It’s the specificity of the genre that I think really determine its classic status. Otherwise it transcends the genre and then becomes real literature. I think Hoffmann is trying to elevate genre fiction to literature status in order to consider it classic. That’s why Hammett is analyzed to death by academics whereas much more imaginative writers and more entertaining writers are repeatedly overlooked. It is absurd, as J. points out, to exclude Carr’s brilliant works because he isn’t “literary” or his stories “don’t move us.” Isn’t fiction really about the power of the imagination first and foremost? I have always felt it to be the first criteria to judge a writer on. I’m in a minority, I know.

Hoffmann’s point about a classic being translated into other languages also is valid, though these days so much of popular bestselling fiction gets translated into many languages. Making a bestseller available to a wider audience by translating it isn’t so much about its classic or literary status as it is about making money for foreign publishers, the author and the author’s agent. Will the Stieg Larsson novels be considered classics fifty years from now? I hope not.

The paperback originals (and other books) listed at the end are far from “crime classics” as Hoffman outlines the criteria. I say that most of them are indeed cult classics especially Hallas’ and Marlowe’s books both of which are popping up all over the internet on the book blogs that love to discuss noir, hardboiled and “pulp” (a category becoming more generic and less specific as time goes by) fiction. I have never heard of Simon Troy or Ted Lewis or ANY of their books. But I know I’m going to go looking for those two titles now and also Davis’ book – she’s a writer I have read little of but who I keep coming across in my book hunting travels but keep passing over.

WHISPER HIS SIN may, in fact, be a true classic not in ALL of crime fiction but in the realm of gay noir fiction, a subgenre that admittedly is a very small subset of the larger genre and has a very small following of which I am proud to call myself one of the cognoscenti.

April 4th, 2012 at 11:28 am

Let me apologize for calling #8 J. Morris, John (unless your name is John). I was lazy and saw J.F. Norris name by mistake.

I agree it is easier to define genre or sub-genre classics than fictional classics. My favorite genre is mystery lite, Norbert Davis’s work when discovered reaches the reader of that genre even today. Gregory Mcdonald’s FLETCH is a classic for the sub-genre, but the rest of the series is not.

But classic can be overused (much like I just did).

Steve, (from #10), yes, time is a key part of what is a classic. But it depends on what you mean by classic. Will the work live forever? Is the work relevant to what followed?

#7. Josef bring up Homer’s ODYSSEY. Yes, it is a classic because it is still read and taught in schools. It remains relevant to modern society.

April 4th, 2012 at 11:50 am

What a stimulating discussion. A few points:

1) I like to make a distinction between the terms classic and classical, the first a measure of quality, the second describing a particular type of work. Thus, THE MALTESE FALCON is a classic but not classical, while an average novel by John Rhode is classical but not classic. (Just as many of Gershwin’s popular songs are classic but not classical and some obscure composer’s failed symphony is classical but not classic.)

2) As for the Ellery Queen team, dismissing them from classic status because they don’t appeal to the present generation may be too hasty. For one thing, I understand that in some parts of the world (notably Japan) they are still popular, and it is always a possibility that their great appeal is skipping a generation. There have been great authors (F. Scott Fitzgerald, for example) who went into eclipse late in their lives or after their deaths but were rediscovered by later readers and critics. And some books (MOBY DICK for one) were unappreciated flops when they first appeared and only were recognized as classics decades later.

3) Whether WHISPER HIS SIN or any other individual title can be called a classic, I think Vin Packer’s work will live on as a reflection of her times. Successful as she’s been under various names, she has yet to receive her due.

4) I’m not so sure John Dickson Carr didn’t “possess literary qualities,” at least some of the time.

April 4th, 2012 at 2:25 pm

#14. Jon.

What role does a critic play in determining if a book (or whatever) is a classic?

And you made a good point about EQ.

April 4th, 2012 at 2:44 pm

This is a delightfully written and thoughtful analysis. My own understanding of a literary ‘classic’ is a work that sufficiently renews its referents with each generation to be timelessly appealing.

Perversely, the referents change with every generation. For example, the eponymous vicar of Wakefield was accepted as transparently benign by the 19th century reader but some 20th century critics read him as Goldsmith’s sly parody of Anglican hypocrisy. And so it goes.

Perhaps it is that very polymorphous mutability that grants a classic immortality.

April 5th, 2012 at 9:10 am

Some questions: Is it typical for a crime classic that it is made into a movie? Should crime classics be read in school? Are the best crime novels by Patricia Highsmith and Chester Himes crime classics?

By the way, I agree with John Yeoman’s opinion.

April 5th, 2012 at 10:06 am

Josef, any famous book is likely to have been adapted for film. Crime novels tend to be visual stories which make them even more appealing.

All classics should be read in school so to expose the young reader to the best of all genres of fiction. Which classics would depend on the reading level of the students.

I don’t consider Highsmith or Himes work as classics, but worthy work to be remembered.

April 5th, 2012 at 12:15 pm

Michael–I don’t have any pat answer to the role of critics in making a classic, but all of the books we think of as classics have been written about by critics and historians, whether genre specialist (like Boucher or Haycraft) or concerned with the wider world of literature. The opinion of a critic or two isn’t going to make a classic any more than popularity alone, but there’s a critical consensus on the classic stature of some books and writers. Ross Macdonald’s literary reputation was made less by Boucher (who was practically Macdonld’s press agent) than by mainstream novelists Eudora Welty and William Goldman. (And Macdonald is another writer who has gone into inexplicable critical eclipse since his death. Who would have thought David Goodis would be canonized in the Library of America before Ross Macdonald? He’ll be rediscovered, though, as will John D. MacDonald.)

Josef–On the movie question, while many (and possibly most) of the classic crime novels have been filmed, so have many more lesser ones. Some of the more cerebral detective stories (Queen, Carr, etc.) would be very difficult to film successfully. I don’t see very much correlation between film adaptation and classic status.

April 5th, 2012 at 1:25 pm

#19. Jon, how much of the dated appeal of Travis McGee’s lifestyle will be held against John D. MacDonald in the future?

Can film overshadow a classic book? Hammett’s leaps to mind (especially THE THIN MAN), but Gregory Macdonald’s FLETCH was one of the best books to reflect its era, yet the movie overshadows it in the memory of the public.

April 5th, 2012 at 8:02 pm

Thanks for the laugh, Michael, since as it happens my first name IS John! But my nom de plume (I write fiction, poetry, and criticism) has always been J. Morris, as there’s another John Morris out there publishing poetry, the dirty rat. (I did a piece on The Three Coffins recently that was issued as a CADS supplement.)

Nothing to add re classics other than: 1) Good discussion! and 2) ok, at his very best, Carr could sometimes conjure up a bit of literary style.

April 5th, 2012 at 8:44 pm

J. “John” Morris —

Thanks for stopping by. We promise not to confuse you with J. F. Norris again, also John!

Michael in Comment #20 —

I agree with Jon Breen. I have a feeling that Travis McGee is a great candidate to make a comeback in popularity. He’s dated now, I’d have to agree, but as time goes one and we get away from his bestseller days, maybe we can get a better (and more specific) perspective on what gave his adventures such an impact then, if not now.

Or maybe it will be MacDonald’s non-McGee books which will survive longer, which would be quite a turnaround, since it was McGee that made MacDonald a household name, no doubt about it.

Why the steep decline for Ross Macdonald’s books, though, I really can’t say. But time has caught up with Goodis, a cult author for years if there ever was one, and maybe Macdonald will be a hot author again. I’d love to think so.

April 5th, 2012 at 8:48 pm

Michael, going way back to Comment #9, where you said:

“…the job of the critic is to describe and inform the reader what to expect from the book (or whatever) so the reader can decide for him or herself if they would enjoy reading it.”

This sounds more the role of a reviewer to me. I’d say a critic is somebody who goes into more depth. Someone who can tell you why you should have enjoyed something when you didn’t; or contrariwise, why you shouldn’t have enjoyed something you did.

April 5th, 2012 at 9:20 pm

J. Morris, I second Steve in hoping you visit again.

As for Ross and John. Right now the attention seems to be aimed at the fifties pulp hardboiled writers that inspired so many of today’s writers of violent bloody thrillers rather than characters created in the sixties.

April 6th, 2012 at 10:43 am

Regarding JDM: Writers who are associated with the attitudes and mores of a particular time will seem dated for a while shortly thereafter, but when we get farther away from their time, their merits may be appreciated anew. Again, F. Scott Fitzgerald is a good example. I agree with Steve that the non-McGees may eventually be regarded as JDM’s most important work. When the first critical studies of his work came out, I was surprised they focused so much on the McGees and so little on the earlier stand-alones.

Steve’s distinction between reviewer and critic (though the line is sometimes hard to draw) helps answer the question of the critic’s role in making a classic. The early reviewer, right or wrong, has little to do with recognition of a classic, which takes time to establish, but the later critical perspective is indispensable to it.

By the way, J. Morris’s chapbook on Carr’s THE THREE COFFINS is an amazing piece of work, probably unprecedented in the extensiveness of its analysis of one detective novel’s plot.

April 6th, 2012 at 3:24 pm

Thank you so much, Jon. That’s a compliment I’ll savor, coming from you, whom I’ve read all my life.

April 6th, 2012 at 11:28 pm

Concerning JDM, there is a very interesting site which has discussed many of his books and stories: http://thetrapofsolidgold.blogspot.com