Sat 15 Aug 2020

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: BLOOD MONEY (1933).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

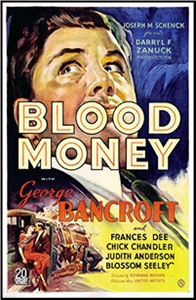

BLOOD MONEY. 20th Century, 1933. George Bancroft, Judith Anderson, Frances Dee, Chick Chandler, Blossom Seeley. Director: Rowland Brown

Where a movie like SOUND OF FURY (reviewed here, and Sweet Lord, how I hate that title!) tries to analyze its characters, a dandy little film called BLOOD MONEY seeks only to understand them, with much happier results: fast-paced and thoughtful, cynical and sentimental, BLOOD MONEY deals out the tale of a bail bondsman (flamboyantly played by beefy George Bancroft) and his sadder-but-wiser gal — a remarkable tum by Judith Anderson, better known for prim, patrician parts in REBECCA and LAURA, in slinky gowns, brassy makeup, and weary sang-froid.

This is a film that sustains itself on attitude rather than plot, but what story there is spins around Bancroft’s sudden infatuation with debutante Francis Dee, who (the script hints) likes men who play rough. Bancroft jilts Anderson for Dee, who ditches Bancroft for a fling with Anderson’s kid brother (Chick Chandler) a bank robber out on bail, then connives to have him betray Bancroft, thus heading the whole cast into shootings, gang war and general aggravation.

That’s the crux of the thing, but BLOOD MONEY doesn’t waste a lot of time on it; what it does is limn some vivid cameos of colorful characters and let them live and breathe on the screen a while. Chandler and Dee do a fine, understated sketch of flashy self-destruction, and there are some memorable bit parts of gang bosses, bent politicos and crooked cops. There’s even a flamboyant lesbian. But what stays in the mind is the relaxed and altogether real-feeling relationship between Bancroft and Anderson, as written by Hal Long (who also wrote ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES) and directed by Rowland Brown, a talented director whose penchant for violence got him black-listed.

The scene where Anderson and Bancroft break up tugs at all the right strings: it’s upstairs at Anderson’s speakeasy, with everyone partying down below. Bancroft tries to let her down gently, she grimly hands him his hat, and he slowly walks downstairs, feeling like a heel. As faded, jaded Blossom Seeley croons “Melancholy Baby,” he tosses off a last drink at the bar and mutters, “That song kills me,” before walking out of her life. It’s a moment worthy of the great romantic films, and all the more moving for showing up in a film as fast and tough as this one.

August 15th, 2020 at 6:58 pm

I have seen Blood Money and have little to comment on, but I was surprised at how appealing Judith Anderson was; always the opposite in her other projects.

August 15th, 2020 at 7:35 pm

Dan nails this one, a surprisingly strong star performance from two actors more often cast in strong character roles rather than leading roles.

Anderson is particularly appealing, and Bancroft scores well in the kind of role later played more often by the likes of Wallace Berry or Brian Donlevy.

This one is fast, violent, poignant when it wants to be, and cynical when it needs to be with numerous good bits, and a rare straight role for the usually humorous Chandler.

August 16th, 2020 at 12:57 am

Here’s something I did not know: This was Judith Anderson’s first full length movie, and she did not make another until REBECCA in 1940.