Thu 11 Feb 2021

A Book! Movie!! Review by David Vineyard: PHILIP MacDONALD – The List of Adrian Messenger // Film (1963).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[17] Comments

PHILIP MacDONALD – The List of Adrian Messenger. Col. Anthony Gethryn #12. Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1959. Bantam A2186, US, paperback, 1961; #F2643, 1963. Herbert Jenkins, UK, hardcover, 1960.

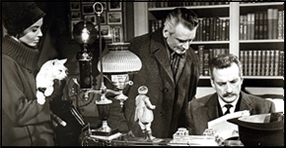

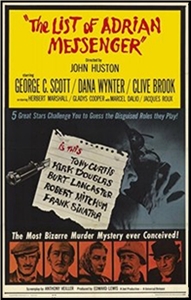

THE LIST OF ADRIAN MESSENGER. Universal-International, 1963. Kirk Douglas, George C. Scott, Dana Wynter, Jacques Roux, Herbert Marshall, Clive Brook, Gladys Cooper Guest Stars: Tony Curtis, Burt Lancaster, Frank Sinatra, Robert Mitchum. Screenplay by Anthony Veiller. Directed by John Huston. Available on DVD.

When writer Adrian Messenger asks a friend to use his influence to look into a disparate list of men from all walks of life and all parts of the United Kingdom it seems like nothing but a whim, but shortly after, when Messenger is killed in a plane crash the friend in question turns to Anthony Gethryn to look into the list, almost immediately one fact arises, all ten men died of untimely accidents, including Adrian Messenger, making for a strangely coincidental eleven accidental deaths seemingly unrelated deaths.

Semi-amateur sleuth Col.Anthony Gethryn (The Rasp, Warrant for X) suspects something, and with the help of one of the survivors, a Frenchman, Raoul St. Denis, who coincidentally was once a member of the French Resistance run by Gethryn anonymously in the war, it soon becomes apparent Adrian Messenger was onto something sinister and deadly.

At first Gethryn’s friend at the Yard, Lucas, and his old ally Inspector Pike, think Anthony is jumping at conclusions, but between a dying message left by Messenger in the lifeboat with St. Denis, and an expanding investigation it becomes clear there is a killer on the loose, one who has carefully over the years eliminated anyone who might know him for an as yet unknown reason.

A series, if not serial, killer who eventually tallies sixty seven murders over much of the globe, all disguised as accidents, a criminal genius who only has two more deaths to go, an old man and a fourteen year old boy, the Marquis of Gleneyre and his grandson, heirs to a considerable fortune.

Worse, there may be nothing the law can do to stop him.

The List of Adrian Messenger is the final novel in the Anthony Gethryn series that began at the height of the Golden Age of the Detective Novel from a writer whose books such as The Rasp, Warrant for X, Escape, Mystery of the Dead Police (X vs Rex), and Patrol led him to Hollywood and a long career as a screenwriter penning everything from Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca.

It is not the end of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction; writers such as Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, John Dickson Carr, and John Rhode, not to mention Ellery Queen and Rex Stout in this country, continued to write for sometime after MacDonald’s death. Still it is coda to the era, and works both as a fair play mystery novel, and not unusual for MacDonald, as a suspense novel and a thriller, making it a compellingly readable mix of the old and the new.

Series killers, even serial killers, weren’t new to the Classical Detective story. Christie’s The Alphabet Murders, Conan Doyle’s Sign of the Four and A Study in Scarlet, MacDonald’s own Mystery of the Dead Police and Murder Gone Mad and the plot here has some interesting ties to MacDonald’s plot for his original screenplay for Circle of Danger in the motive for the killer.

What interests me here is where the 1959 novel and the fine 1963 film by John Huston vary, because while the Huston film uses large chunks of dialogue directly from the novel it varies importantly from the book on one key point, one that puts Anthony Gethryn in the mainstream of the high handed Great Detective model and ironically sets him against the entire genre.

So at this point:

Spoiler Warning!

Spoiler Warning!

Spoiler Warning!

One of the key personality traits of the Great Detective has always been his high handed behavior, hiding key facts from his Watson, playing God (almost all the Ellery Queen novels after The Door Between are concerned with Ellery’s unease playing God in his role as Great Detective), and acting as a figure of justice and vengeance and not merely law. When Sherlock Holmes at the end of “The Speckled Band†mused he wasn’t much bothered by the fact his actions led to the death of the brutal doctor Conan Doyle could hardly have imagined how many writers would take it to heart.

Philo Vance practically encouraged the murderers he caught to commit suicide. Even Charlie Chan saw quite a few of his killers dying by their own hand rather than waiting for a messy trial and even Agatha Christie’s seemingly cozy Miss Jane Marple defined herself as Nemesis and not merely a puzzle solver. John Dickson Carr’s Dr. Gideon Fell burns down a house to keep the police from charging a murderer in The Man Who Could Not Shudder to avoid a miscarriage of justice.

But few act as decisively as Anthony Gethryn does here.

In the film, as in the book, the killer, George Brougham (Kirk Douglas), is known about half way through the book, but he has left no trail. The police have nothing but suspicions, and short of catching him in the act, and nothing suggests he will be that stupid, he only needs to wait patiently to kill the fourteen year old heir who simply cannot be watched for the rest of his life.

Knowing that Anthony Gethryn (George C. Scott) deliberately lets Brougham know that he is close to uncovering his secrets and forces him to try to kill Gethryn, the attempt, and Brougham’s fate sealed at a fox hunt (which plays a large part in film and book though more so in the film because director Huston was devoted to riding to the hounds on his Irish estate) Brougham meeting a satisfyingly grim justice impaled on a farm implement he meant to use to kill Gethryn.

At which point the film pauses to show us the clever make up disguises used by Douglas and his four major guest stars.

And this is where the movie lets down fans of the book somewhat, because the ending of the book is considerably more stunning, Gethryn telling Lucas after he has seemingly walked away from the case.

Gethryn doesn’t just set a trap to capture Brougham, though he does use the young Marquis as bait to catch Brougham in the act, he knows that short of allowing Brougham to kill the boy in front of witnesses the law has almost no case, so Gethryn, St. Denis, members of the French resistance, Hispanic allies and friends of Gethryn, and the Marquis and Adrian Messenger’s cousin Jocelyn (Dana Wynter in the film) lure George Brougham to California and arrange for him to be hoist on his own petard, to die in an accident while fleeing a foiled attempt to kill the boy.

In short they conspire to and successfully execute George Brougham, by “accident,†or as St. Denis notes in the books final line, “What you would call, I think, a justice poetic…â€

I think it is that ending that gives the novel a unique place in the history of the Golden Age of the Fair Play Detective novel. The world has changed, and murder is no longer committed by gentlemen who can be expected to conveniently put a bullet in their own brain rather than face trial, imprisonment, and shame.

George Brougham has no shame. He is a modern killer, amoral, a sociopath, a cunning murderer willing to kill dozens to achieve his goal. He is evil, but a more mundane and frightening kind of evil than a Fu Manchu or a Moriarty. He is a human monster born out of WW II, ruthless, clever, and above the ability of the law to stop him.

The oh so civilized rules of the Golden Age Detective Novel have broken down and no longer apply, it is no longer just a game. The victims are ordinary men and potentially a boy who has harmed no one. The killer is as amoral and efficient as the monsters who marched millions into ovens to die in death camps, and his motive isn’t political, it’s money and power.

To defeat him, Anthony Gethryn has to forgo the academic and cool analytic of the Great Detective he becomes an avenger as much as a Bulldog Drummond, James Bond, or Mike Hammer, an agent of chaos and not order, the classical role of the Great Detective.

Hercule Poirot will find himself in the same role in his final adventure, Curtain. It is a concession of the Golden Age to the modern world. The brain and the intellect is not enough in the face of evil, the dragon must be met on his own level. Which at least, for me, makes The List of Adrian Messenger a fairly revolutionary statement from one of the masters of the Golden Age puzzle.

Murder is no longer a game and its victims no longer pawns. That idea that real people are dying and murderers walk among us is almost more than the fragile conceit of the Golden Age can bear.

I think a fairly good argument can be made MacDonald was putting the audience and his fellow writers on notice that the cozy comfortable world they created was no longer enough for readers and no longer sustainable as mystery fiction. You have to wonder whether he would have carried Gethryn beyond this point if he had lived longer, or if he had said all that could be said about the Great Detective from his point of view.

February 11th, 2021 at 6:57 pm

A very very interesting review, David. Thanks very much!

I remembering seeing the movie when it first came out, but all I recall of it, of course, is the ending. Everything else is gone. I’m sure I’m not alone in this regard. I think this is a movie that the gimmick ending “ruins” the rest of the film in everyone’s mind.

I wonder (but only idly so) why Huston decided to go that way.

I also wonder (I have some time on my hands) why MacDonald decided to pull Gethryn out of mothballs for this one. Except for one novelette in between WARRANT FOR X and this one, it had been 22 years since Gethryn solved a case.

Was this (I wonder) part of his deliberate statement to detective fiction readers you suggest in your final paragraph?

Obviously I am full of wonderment tonight. Thanks again.

February 11th, 2021 at 7:43 pm

Lament for the Murderers

– A.D. Hope

Where are they now, the genteel murderers

And gentlemanly sleuths, whose household names

Made crime a club for well-bred amateurs;

Slaughter the cosiest of indoor games?

Where are the long week-ends, the sleepless nights

We spent treading the dance in dead men’s shoes,

And all the ratiocinative delights

Of matching motives and unravelling clues,

The public-spirited corpse in evening dress,

Blood like an order across the snowy shirt,

Killings contrived with no unseemly mess

And only rank outsiders getting hurt:

A fraudulent banker or a blackmailer,

The rich aunt dragging out her spiteful life,

The lovely bitch, the cheap philanderer

Bent on seducing someone else’s knife?

Where are those headier methods of escape

From the dull fare of peace: the well-spiced dish

Of torture, violence and brutal rape,

Perversion, madness and still queerer fish?

All gone! That dear delicious make-believe,

The armchair blood-sports and dare-devil dreams.

We dare not even sleep now, dare not leave

The armchair. What we hear are real screams.

Real people, whom we know, have really died.

No one knows why. The nightmares have come true.

We ring the police: A voice says “Homicide!

Just wait your turn. When we get round to you

You will be sorry you were born. Don’t call

For help again: a murderer saves his breath.

When guilt consists in being alive at all

Justice becomes the other name for Death.â€

February 11th, 2021 at 7:43 pm

Disclaimer:

I’ve never read Adrian Messenger, the novel.

(This will be remedied in the near future.)

Adrian Messenger the movie – well …

This is an early example of “filming the deal”.

As nearly as I can reconstruct, Kirk Douglas and John Huston had existing deals with Universal that everybody wanted to burn off as quickly (and profitably) as possible.

After a few false starts, somebody found the Messenger novel, which apparently involves a Master of Disguise (correction welcomed if needed).

It was pitched to Douglas (the disguise business) and to Huston (the fox hunting angle) and the deals were made: Douglas would get to show off and Huston could film the hunts on his Irish estate.

If you see the movie again, you might take note that it’s a really low-budget production: it’s in black-and-white, and the interiors are mainly shot in Hollywood (with the Beverly Hills Raj in full array).

So whatever “statement” Philip MacDonald might have had in mind – I guess that was the McGuffin.

I haven’t even brought up the reason for which Messenger the movie is best known these days – given that it’s beside the point of the comment.

I can explain if you’d like; I have on some other sites.

If you’d like a preview, look up an actor named Jan Merlin …

February 11th, 2021 at 7:44 pm

Huston may not have been in charge, no auteur stuff here unless Kirk Douglas fills that role.

February 11th, 2021 at 7:46 pm

And yes to all Mike Doran has written just above.

February 11th, 2021 at 7:56 pm

As another followup to Mike’s comment, there is on the film’s IMDb trivia page, lots of backstage info about the file, and yes, his mysterious comment about Jan Merlin is expanded upon:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057254/trivia

February 11th, 2021 at 8:04 pm

I didn’t expect such scintillating insights from a review of this film. I was very well rewarded. A fine set of ruminations; much to mull over. I haven’t read the book but only now do I realize its significance.

Evolution of evil in the detective novel: I suppose I agree with all the reviewer states. Grim efficiency did absorb the globe after WWII (arguably even after WWI).

Did Conan Doyle see it coming? Well in ‘Speckled Band’ there’s also this:

“Violence does, in truth, recoil upon the violent, and the schemer falls into the pit which he digs for another…”

As for the film: I actually enjoy the film quite a bit. It’s a fave of mine for both atmosphere and also, the setting of English fox hunts (do they still have them?)

The gimmicky movie ending is questionable but somehow redeemed by the ‘fun factor’.

Huston is the real puzzler. What a Mephistophelean personality. And for such a knowledgeable film craftsman he made some oddball directorial choices. Not just this film but several others. In his interview with Bill Moyers he clearly shows that he knew every time, the ramifications involved; although he was naturally speaking in some retrospect and he was a phenomenal drinking man (which I greatly admire). I still marvel at the story of he and Peter O’Toole riding horseback, both stark naked and potted drunk, across his estate. Anyway his statement was something-to-the-effect that when the studio wanted a bad picture from him, he was willing to comply with that stupidity, as avidly as when they wanted a great picture from him. I suppose it’s rather like saying he was ‘beyond having to prove himself’.

This is just my recollection of the interview, I’m open to correction on anything I’ve stated.

Anyway the remaining plum in the pudding of the ‘Adrian Messenger’ (movie) is the performance of Kirk Douglas. Gad, what arrogance; what swagger. He really seemed to be enjoying his role.

‘Evil has it’s heroes as well as Good’

–duc de la Rochefoucauld

February 11th, 2021 at 8:23 pm

Back to Kirk Douglas: The List of Adrian Messenger is a Joel production, one of Douglas’s companies.

February 11th, 2021 at 9:35 pm

Steve,

I suspect like Holmes in THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES Gethryn was just too perfectly suited to this story not to use him, and MacDonald may also have been aware this might be his last book and want to revisit past triumphs.

Then I really do suspect he had something to say about the Golden Age of the Mystery.

And while I don’t doubt Douglas control over this, he had done the same thing working with Kubrick in the same general time frame, Huston was always a literary director, and here he hews pretty close to the novel, some scenes, as in THE MALTESE FALCON lifted directly from the book.

As for being filmed in Hollywood, there was no real reason to go too far afield at the time since shooting anything but exteriors in England would have been pointless.

It’s shot in black and white not because it was cheaper, but because the gimmick of disguise would not have worked in color, the techniques to make it work just didn’t exist at the time (you could argue they barely work in the film save in Douglas case), and a bunch of waxy looking actors in obvious putty would have done no one any good. I suspect that decided the black and white aspect more than anything else.

I imagine too the interiors and much else had to do with this being an old fashioned mystery thriller harkening back to an earlier kind of film. It is not beyond Huston to have chosen to make a film about the most artificial kind of story with a look of artifice as well as saving a buck. For all that I cannot say the production looks cheap. The detail in many scenes is far beyond what cheap sets look like.

Huston and Hitchcock both shots sets largely with interiors in this era, including PSYCHO. I wouldn’t read too much into that aspect. Huston tended to shoot on location when he could get a vacation out of it like THE AFRICAN QUEEN or NIGHT OF THE IGUANA, not just for the sake of location shooting.

What is remarkable is that both Douglas and Scott could easily have chewed the scenery in this like two angry pit bulls and instead play in fairly seriously. There are some fine chilling moments, particularly when Douglas reveals himself a little at the dinner table in telling the story of his father’s death by wolf and how he tracked them down, and one of my favorite lines, Scott’s “Evil is.”

Another bit I particularly liked is Mitchum’s , the most extensive of the cameos, and one that doesn’t fool anyone, but which is a nice bit anyway with a fair to middling Cockney accent that somehow still sounds like Mitchum.

But again, while the film is just an entertainment whether you like it or not, I think MacDonald is saying something here in the book. The book is more interesting if you know some of MacDonald’s short fiction in the post War era and one of his few novels, the non series GUEST IN THE HOUSE which features a sort of professional house guest who moves in on a family, but when they are in danger reveals his wartime skills as a killer can be very useful.

That taken with the screenplay for CIRCLE OF DANGER suggest to me MacDonald was likely saying something very like what I suggest with this book about the limits of the Pre War Golden Age Detective novel.

February 11th, 2021 at 9:54 pm

My favorite bit of dialogue from the movie, spoken by Douglas:

“Two angles equal to a third, are equal to each other.”

February 12th, 2021 at 8:34 am

Someone should mention Jerry Goldsmith’s eerie, evocative score, reminiscent of Prokofiev’s “Montagues and Capulets” in ROMEO AND JULIET

February 12th, 2021 at 1:26 pm

Dan, Thank you for being that someone.

February 12th, 2021 at 2:46 pm

One minor correction: Gethryn isn’t in “The Rynox Murder” (which doesn’t really have a detective at all).

February 12th, 2021 at 2:58 pm

You’re quite right, Jonathan, and I’ve retroactively edited it out of the review. Now only you and I will know, and thanks!

February 12th, 2021 at 8:03 pm

Jonathan O.

Quite right, but he is in the Michael Powell movie RYNOX, albeit not as a detective. A curiosity I can’t explain.

February 12th, 2021 at 8:51 pm

RYNOX was at one time available on YouTube, but it seems to have disappeared. I can’t even find it on DVD. Am I looking in all the wrong places?

February 18th, 2021 at 11:33 am

Belatedly:

Evil does exist. Evil IS.

Not George C. Scott’s line, but Kirk Douglas’s.

(OK, George Brougham’s, but you get the idea.)

And he says it to the Fourth Wall.

If memory serves, this line made it into the trailer.