Search Results for 'Inspector Hanaud'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 18 Apr 2020

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

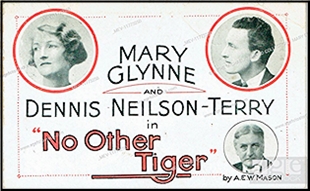

A. E. W. MASON – No Other Tiger. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1927. George H. Doran, US, hardcover, Doran, 1927. Reprinted in the UK several times in paperback. Stage play (see bottom photo): First produced at Opera House, Leicester, 3rd December and St. James’s Theatre, 26th December 1928.

A. E. W. Mason, bestselling author, playwright, spy, producer, and literary bon vivant, is best remembered today for penning one of the classics of the adventure genre, the often filmed The Four Feathers, but to modern mystery readers he is equally known as the creator of Inspector Hanaud, who with his “Watson,†Mr. Ricardo, appeared in popular novels such as The Prisoner in the Opal, They Wouldn’t Be Chessmen, and his most admired classic The House of the Arrow, so it may come as some surprise that his best mystery novel, a fast paced tale of adventure, revenge, madness, mystery, and atmosphere not only doesn’t feature Hanaud, some don’t even classify it with his mystery novels.

No Other Tiger opens in Burma.

There is a rough truth, no doubt, in the saying that adventures occur to the adventurous. But fantastic things may happen to anyone. No man, for instance, was ever less fantastically-minded than Lieutenant-Colonel John Strickland, late of the Coldstream Guards. He disembarked from the river steamer at Thabeikyin and motored by the jungle road over the mountains to the Burma Ruby Mines at Mogok with the simple romantic wish to buy a jewel for a lady. Yet in that remote spot, during the sixty hours of his stay, the first fantastic incident happened to him, of a whole series which was to reach out across the oceans and accomplish itself in the fever of lighted cities.

Within hours of his arrival in Burma a man is killed, Maung H’la, who is apparently mauled by a tiger,and true to his nature Strickland takes up his weapon for a dangerous tiger hunt with the local hunter wounded, a hunt where Strickland finds no tiger, but a savage man, a European … “no other tiger passed that way that night,†he encounters in the jungle.

Mason splendidly evokes the danger and the suspense of the hunt carefully building up the lore of tiger’s danger ( “You’ll hear him suddenly snarling and tearing the kill at the foot of your tree, and you’ll find the impulse to loose off your rifle at that jungle-cat overwhelming. Yes, even though I have warned you! You’ll feel that you must! No other sin in your whole life will ever tempt you more.â€) and even more carefully builds to the moment Strickland encounters the human tiger.

Strickland’s first impression of him, after his shock of surprise, was of enormous power, the power of an animal… For the face he saw was not merely haggard and lined, but to Strickland’s strained fancies, horribly evil, evil to the point of majesty… evil seemed to flow from this man, so savage, so furtive he looked, such a mixture of cunning and cruelty was stamped upon his features… He stood out in the open, his eyeballs glistening in the moonlight, the sweat shining on his face; and he moved his head slowly from side to side like a great cobra before he strikes. There was something bestial, something subtle. Strickland actually shuddered in his retreat. Thus, he thought, must Lucifer have looked on the morrow of his fall.

The dead native, it seems, had once served in England and was something of a scoundrel suspected of something illegal there, and he recently panicked when he saw the lean tigerish European arrive. And soon Strickland discovers that Lady Ariadne Ferne, the woman he came to Burma to buy a fabulous jewel for, is tied to Maung H’la and the mysterious tiger man through her friend Corinne, the famous dancer, who according to Commissioner Thorne would have stood in the dock with Maung H’la if the latter had been tried.

On return to England, as you ought to expect from this era, Strickland learns Lady Ariadne is engaged to another, and being a good sport gives her the jewel anyway, but soon, through her crowd he meets the beautiful Corinne and her fiance, the Spaniard Leon Battchilena, a rotter if there ever was one.

It becomes Strickland’s job to untangle the web that connects Maung H’la and Corinne to the too trusting Adriadne and the mysterious man in the jungle, a mystery that involves a handsome young English bridegroom, a miscarriage of justice, terrible suffering (“he must always have silk against his skinâ€), a cold blooded murder, and a man turned into beast whose inhuman vengeance is key to the whole business and who must be confronted by Strickland and his beloved Adriadne in a deadly tiger trap set by the treacherous Corinne (a change there was in the very atmosphere of the room, not so much a chill as a tension. Corinne had a feeling that now at last she was put upon her trial ) for her innocent friend as she schemes to escape justice for her crimes.

This colossal figure of a man, with murder and revenge and violence in his thoughts… was making for the window, to shut off all possibility of escape.

The theme of the book is the Victorian horror of atavism that inspired Stevenson’s Hyde, Stoker’s Dracula, and Doyle’s Hound, for though an innocent man is the victim, inhuman temper, strength, and bestiality make him impossible to identify with or pity, he is a beast that has to be put down an epic tragic villain (he…coupled his ferocity with cunning. He took big chances, but not small ones). Mason is never better than when he is portraying the almost inhuman qualities of his two legged tiger who he wisely keeps just outside the readers’ sight as a deadly shadow for much of the book.

Better yet are the portrayals of some quite strong, intelligent, modern (for the time), and fierce women (“She’s dead now. I know it. She’s dead now,” and the cry ringing out through the windows across the moonlit lawn and glistening river—just at the hour when Elizabeth Clutter actually did die.).

Even when they faint it isn’t without good reason.

It is easily Mason’s best mystery novel, with solid detection, mystery, a line of suspense, a splendid villain and some equally splendid characters good and bad (Strickland for one has twice the nerve and brains of most silly ass heroes of this era), even a comical French policeman has quiet dignity.

It’s only a shame it was never filmed though a BBC radio play version is available that rather gives away all the mystery element in the opening.

Yes, it is melodrama, but it is well written melodrama.

Any thriller is only as good as its villain, and this one has a dandy, worthy to stand by those great throwbacks of Victorian nightmare.

And there is that memorable simple line that says so much and provides the books perfect title.

No other tiger passed that way that night.

No other tiger…only the human one.

Mon 30 May 2016

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

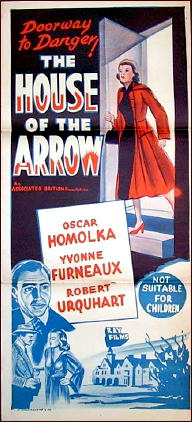

HOUSE OF THE ARROW Associated British Pictures, UK, 1953, Oskar Holmoka, Yvonne Furneaux, Robert Urquhart, Josephine Green, Harold Kasket, Pierre Le Fevre. Screenplay by Edward Dryhurst, based on the novel by A. E. W. Mason. Directed by Michael Anderson.

Alfred Edward Wooley Mason was a bestselling novelist whose works included such classic tales of adventure and mystery as The Four Feathers, No Other Tiger, Sapphire, Fire Over England, The Drum, and stories such as “The Crystal Trench†(adapted on Alfred Hitchcock Presents with Hitchcock himself directing); a literary icon whose circle of friends and collaborators in theater included Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Ford Maddox Ford, Anthony Hope Hawkins (The Prisoner of Zenda), and Stephen Crane; an agent of British Naval Intelligence whose pre-WWI Spanish network would still be functioning successfully, and much to the benefit of the Allies, in the Second World War and into the post War era; and, perhaps most importantly here, the author of five acclaimed mystery novels and one short story featuring Inspector Hanaud of the Sureté who was the inspiration for Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and his “little gray cells.â€

House of the Arrow is perhaps the most famous of the Hanaud novels, as evidenced by it having been filmed three times, first in 1930 with Benita Hume and Dennis Nielson-Terry as Hanaud; then in 1940 with Diana Churchill and Kenneth Kent as Hanaud; and, finally, this version in 1953 with Yvonne Furneaux and Oscar Holmoka as Hanaud.

This version, updated to modern post-war France begins in Dijon in the Burgundy region of France where Jeanne Marie Harlowe, an elderly and sickly widow, has just died apparently in the natural order of things. At the reading of her will Madame Harlowe leaves her fortune and estate to her adopted daughter Betty (Yvonne Furneaux) much to the consternation of her brother-in-law, from her first marriage Boris Waberski (Harold Kasket), who believes the fortune should go to him.

Shortly afterward Waberski makes a formal accusation against Betty of having murdered her adopted mother, prompting Betty’s companion, Englishwoman Ann Upcott (Josephine Green), to write Betty’s British solicitor for help.

Responding is Jim Frobisher (Robert Urquhart) who arrives in Paris to talk with the officer of the Sureté assigned the case, Inspector Hanaud (Oskar Holmoka, dapper rather than rumpled for once, even the famous eyebrows tamed), who seems quite surprised his upcoming visit to Dijon is known since he only just decided to go.

Hanaud settles the phony case brought by Waberski in short order, but things aren’t as they seem, he is certain of one thing: “If murder was done I mean to know, and I mean to avenge.†And what with a mysterious seller of illicit chemicals, accusing letters popping up everywhere, mysterious voices, and a missing arrow — it’s waxed point preserving an exotic untraceable poison — it becomes clear Hanaud has every reason to be suspicious.

What, if anything does the empty house next door, once occupied by the Germans, have to do with the mysterious goings on? Who is writing the poison pen letters and why? Why are the two young women so secretive? Whose voice did Ann hear the night of the murder, and why does the clock she saw seem smaller in daylight? Where is the mysterious poisoned arrow Hanaud discovered referenced in a book from the Harlowe library at the drug sellers business?

When a second murder, that of the seller of illicit drugs, occurs Hanaud must act fast before a third murder and injustice can further complicate matters.

Mason’s longish novel is savagely condensed, but thanks to atmospheric direction by Michael Anderson (Around the World in 80 Days), good use of shadow and light and clever but unobtrusive camera angles in limited but well done sets, above all Holmoka’s delightful turn as the vain, brilliant, playful, and very Gallic Hanaud, and a script that manages to keep things mostly clear in the mind of the viewer while still preserving a few surprises, this is a superior mystery film.

Though, as in the novel, and in many mystery novels and films, Hanaud causes quite a bit of the tension himself by revealing so little, but at least in this one with some justification.

I first read of this film ages ago in William K. Everson’s The Detective in Film, and it has taken me forty some years to catch up with it, but it proved well worth it. House of the Arrow is a wry, intelligent, atmospheric, fast paced, mystery with a tour de force performance by Oskar Holmoka as Hanaud. Whatever its minor flaws, they are more than compensated for by the films intelligence, wit, and fidelity to the spirit if not the exact word of Mason’s classic novel.

If you are looking for a fine adaptation of a classic mystery novel ably brought to the screen with skill and wit, you could not do better.

Wed 12 Sep 2012

THE HOUSE OF THE ARROW. Associated British Pictures, UK, 1953. Oskar Homolka (Inspector Hanaud), Robert Urquhart, Yvonne Furneaux, Josephine Griffin, Harold Kasket, Pierre Lefevre, Pierre Chaminade. Based on the novel by A. E. W. Mason (Hodder, 1924). Director: Michael Anderson.

This is the third of three adaptations of Mason’s classic detective novel to the screen. The other two (1930 and 1940, respectively) are said not to exist. (If this is not true, I’d like to be corrected on this statement.) I first read the book a long time ago – a Modern Library Giant that contained two other works I also consider classics: Trent’s Last Case and Before the Fact – but alas, never since. (It has since been reprinted in an easy to obtain paperback published by Carroll & Graf in 1984.)

In any case, while I’d like to be able to contrast the book with the film, I cannot. My memory does not go back nearly that far, almost 60 years ago. So I must encourage you to take the comments that follow with as large a grain of salt that you can muster, but they are, I assure you, well intentioned and (I hope) worthy of further discussion.

As good as this movie is – and it is very good – I think what it displays is that no one can make a movie based on a work of detective fiction and have it work as well as it did in printed form. Movies and episodes of various TV series have been made that are excellent detective puzzlers, so it can be done.

I’d include the Jim Hutton season of Ellery Queen shows in the latter category, and many of the Murder, She Wrote series. You can name your own movies, including those made for TV, but I doubt that many of the ones you might bring up were based on printed novels or even short stories, if any at all, and if they were, I’m willing to wager that the original printed version was better.

I’m talking fair play detective fiction, mind you, not suspense thrillers, or noir fiction. Some of the Suchet versions of Poirot stories follow the originals closely, but are they better? I’ve been watching the first season of the Perry Mason television series, for example, and most of the shows I’ve watched are simply awful, with gaps in continuity and logic that are simply bewildering. Maybe they existed in Erle Stanley Gardner’s novels, too, and I’m willing to concede that maybe they were. I’m almost afraid to go back and see for myself.

Perhaps it’s that the pure puzzle category of detective fiction doesn’t translate well to film, or that film people simply don’t know how to do it. They have to jazz up Miss Marple and even Hercule Poirot so much, even to changing the endings (is that really so?), that they could change the names of all the characters and no one would have any ideas where the stories came from.

I think (but as I suggested above, I am not sure) that the producers of this cinematic version of The House of the Arrow intended to follow the story line of the book as closely as possible. I’ll assume that to be the case.

There are plenty of false trails for this to be true, although only a small number of suspects, a French manor house where the murder takes place (if it was indeed murder) so intricately filled with connecting rooms and corridors that Inspector Hanaud of the French Surete must carry floor plans of the building around with him as he goes, a mysterious poison brought back to France from South America (I believe) on an antique arrowhead, and a detective (the aforementioned Hanaud) who is the epitome of Golden Age detectives: jaunty, pugnacious, all-knowing, and positively beaming with delight to be confronted with a case that’s up the challenge of his abilities, of which he can assure you, are second to none.

And Oskar Homulka is positively the right actor for the job. Not particularly handsome, his flair for the dramatic, as well as the comic jest at just the right time, is right on, every moment of the film. The black-and-white photography is superb, near noir-like in the angles that are taken and the mood that is invoked. Dead is an old woman, presumably of natural causes, but some anonymous letters and a disgruntled would-be heir cause suspicion to be aroused.

But I confess, it took me two viewings to follow the story, and while I know who and why, I’m still not sure exactly sure how the many details that put who, why and how fit together in a nicely satisfying whole. Nor is this is not a fair play mystery, one in which you say to yourself “Of course,†and slap yourself on the head with a “Doh†when all is revealed. The book may be equally at fault in this regard. If any of you reading this have read the book more recently than I, or have better memories, can say yea or nay in this regard, please do.

A very enjoyable movie, nonetheless, in spite of this long and perhaps rambling preamble, with lots of thoughts and no complete answers on my part, I’m afraid, but if you’ve read this far, you really ought to see this movie, if it ever comes your way.

Thu 21 Apr 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

This section could be called the Golden Age Traditionalists. Early crime and mystery drama on television is, quite simply, divided into two strands. The British one (namely BBC), which had its roots in Radio and in the Theatre, and the American one (namely NBC), which had its roots in Radio and (in a limited capacity) in the Cinema.

British television (BBC), in the beginning, experienced something of a race in technology. Inventor John Logie Baird’s mechanical system versus EMI-Marconi’s electronic system. In February 1937, the EMI-Marconi system was formally adopted by BBC Television.

The BBC’s Royal Charter made it their duty to “inform, educate and entertain.” The first two were served with TV news broadcasts and with various instructional documentaries. The third element started off as little more than “photographed stage plays.”

It was the lofty, upper-middle-class BBC view of the time that either scenes from West End theatre productions or studio-produced adaptations of artistically intellectual novels made up almost the only “entertainment” programmes.

However, television Crime & Mystery genre history was made in 1937 — when George More O’Ferrall produced the medium’s first (hitherto unperformed) Agatha Christie play, The Wasp’s Nest, on 28 June 1937. The 25-minute TV presentation, broadcast live, starred the portly Francis L. Sullivan, a popular actor of the time who had earlier achieved a great success as Hercule Poirot in Christie’s 1931 West End stage hit Black Coffee.

The other great television genre “first” was the NBC experimental broadcast of Conan Doyle’s 1924 “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs,” transmitted from the stage of the Radio City Music Hall on 27 November 1937 as The Three Garridebs. Luis Hector played Sherlock Holmes and William Podmore was Dr. Watson.

Arriving in the latter part of the literary genre’s Golden Age, BBC presentations included television adaptations of plays by Emlyn Williams (Night Must Fall, 1937), Edgar Wallace (The Case of the Frightened Lady, On the Spot, Smoky Cell and The Ringer, all 1938), Christie (Love from a Stranger, 1938), Patrick Hamilton (Gaslight, 1939) and Edgar Allan Poe (The Tell-Tale Heart, 1939).

Of related interest was a black comedy about 19th century body snatchers Burke and Hare, and their mentor Dr. Knox, in The Anatomist (1939; presented again in 1949). The first actual UK made-for-television genre series was Telecrime (1938-39), a programme consisting of 10 and 20-minute whodunits set to test the viewer on their powers of observation and deductive reasoning.

The BBC hurriedly closed down their Television Service in September 1939 due to the outbreak of war in Europe.

Telecrimes (now plural) returned in post-World War Two 1946, written again by Miles Horton and now with James Raglan as Inspector Cameron. A similar viewer-participation series, Consider Your Verdict, was shown in 1947.

Starting in July 1946, the works of Edgar Wallace continued to be popular with The Ringer, The Green Pack (1947), On the Spot and The Case of the Frightened Lady (both 1948), and The Squeaker (1949) adapted for television.

Joining the Wallace adaptations, among others in the TV Crime & Mystery genre, were G.K. Chesterton’s play Magic (1946), the Anthony Armstrong thrillers Ten-Minute Alibi (1946), and later, in 1948, The Case of Mr. Pelham. In Gilbert Thomas’ Scotland Yard detective play Murder Rap (1946), Desmond Llewelyn played the intrepid Inspector Fearon.

Patrick Hamilton also saw plenty of small-screen time, with Rope (January 1947), featuring young Dirk Bogarde as murderer Charles Granillo, Gaslight (1947 and 1948), The Duke in Darkness (1948) and The Governess (1949).

Fans greeted Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1947) and Martin Vale’s The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947) with glee. Agatha Christie was represented with Love From a Stranger (1947), adapted by Frank Vosper, and Three Blind Mice (1947), the latter written especially by her for BBC Television to mark Queen Mary’s birthday.

There was also a version of Maria Marten, or The Murder in the Red Barn (1947), with William Fox in the villainous Tod Slaughter role. Dorothy L. Sayers (and Miss St. Clare Byrne) had Busman’s Honeymoon (October 1947) adapted for television, with Harold Warrender as Lord Peter Wimsey and Ruth Lodge as Harriet. Toward the end of 1947, a dramatization of George du Maurier’s Trilby (October) was shown, with Abraham Sofaer as the spooky Svengali.

J. B. Priestley’s intriguing drama An Inspector Calls was dramatized in May 1948, with George Hayes as Inspector Goole (the Alastair Sim role in the famous 1954 film version). From May 1948, saturnine storyteller Algernon Blackwood told a chilling Saturday Night Story straight to camera. Anthony Holles was Inspector Hanaud in A.E.W. Mason’s At the Villa Rose (1948). On Christmas Eve 1948, the BBC presented He That Should Come, a Nativity play written by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Under the TV programme banner of Triple Bill (June 1949), Sidney Budd adapted Christie’s Witness for the Prosecution (presented alongside Denis Johnston’s Irish Rebellion play The Call to Arms and Peter Brook’s one-man [Marius Goring] show Box for One). Christie’s body-count play, then called Ten Little Niggers, was produced in August 1949.

At the end of the year, as a part of BBC’s Edgar Allan Poe Centenary (in October 1949), the TV play versions of The Cask of Amontillado, Some Words With a Mummy and The Fall of the House of Usher (all adapted by Joan Maude and Michael Warre) were presented.

Towards the end of the decade, television began adopting regular programming schedules. Emulating the long-standing BBC Radio form, strands like Children’s Television, Sport, Theatre, and Variety began producing their own series and soon established their weekly slots.

Outside of radio (where other genre authors composed works especially for BBC Radio, such as Sax Rohmer with the eight-part serial Shadow of Sumuru, December 1945-January 1946), the TV genre consisted mainly of documentaries — for example, It’s Your Money They’re After (1948), with Scotland Yard explaining some of the then-new and ingenious frauds, and The Man On the Beat (1949), showing how a policeman becomes our protector.

There was also the occasional, early drama series: The Inch Man (1951-52), concerning the adventures of a hotel house detective, and the now-legendary Sherlock Holmes (October-December 1951) series of stories starring Alan Wheatley as Holmes and Raymond Francis as Watson; the stories were adapted for television by Observer film critic C.A. Lejeune. (But more on the TV Sherlock Holmes later.)

1952 saw the beginning of the Francis Durbridge suspense thrillers, bringing UK television’s early Crime & Mystery period to a close.

In the second section of this two-part Evolution of the TV Genre, I will be looking at the same 1930s/1940s period in US television.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Wed 27 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

A. E. W. MASON – At the Villa Rose. Hodder, UK, hardcover, 1910. Scribner, US, hardcover, 1910. Four-act play version: Hodder, 1928.

Silent film: Stoll, 1920 [Hanaud: Teddy Arundell; Miss Harland: Manora Thew]. Sound film: Haik, France, 1930, as Mystere de la Villa Rose. Also: Twickenham, 1930 [Hanuad: Austin Trevor; Miss Harland: Norah Baring], aka Mystery at the Villa Rose. Also: ABPC, 1939; released in the US as House of Mystery [Hanaud: Kenneth Kent; Miss Harland: Judy Kelly].

Reprinted many times, both in hardcover and soft, including: Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hc, 1936; Harlequin 460, Canada, pb, 1959 (both shown).

Middle-aged Julius Ricardo is on holiday at Aix-les-Bains. One evening at the casino he notices Celia Harland, beautiful companion to wealthy Madam Camille Dauvray. Rescued from starvation, and probably worse, by her kind-hearted employer, Miss Harland is now romantically involved with rich young Englishman Harry Wethermill.

Both men are staying at the Hotel Majestic, and next morning Wethermill bursts into Ricardo’s room with the news Madam Dauvray has been murdered at the Villa Rose, her confidante and maid Helene Vauquier bound and chloroformed, and Miss Harland, madam’s car, and all her extremely valuable jewelry are gone.

Wethermill insists Inspector Hanaud of the Paris Surete, also holidaying in the town, aid the local authorities with their investigation, not least in finding the missing girl, even though he appears to be the only person who believes her innocent of the terrible crime.

My verdict: Several undercurrents swirl about the villa and red herrings abound. Was the young woman using her skill as a faux medium to hoodwick her employer and if so, why?

How was a vital witness killed in a cab which did not stop in its journey between station and hotel?

What can be deduced from a pair of cushions?

The identity of the murderer is well concealed. There are clews for readers to spot as they go along, but I missed most of them!

Etext: http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/vllrs10.txt

Sun 13 Oct 2019

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

A. E. W. MASON – At the Villa Rose. Inspector Gabriel Hanaud #1. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1910. Scribner’s, US, hardcover, 1910. Serialized in nine parts in The Strand Magazine, beginning December 1909, as “Murder at the Villa Rose.” Reprinted many times, including Scribner’s Crime Classics, US, paperback, 1979, as Murder at the Villa Rose. Filmed four times: At the Villa Rose (silent, 1920), At the Villa Rose (1930), Le mystère de la villa rose [The Mystery of the Villa Rose] (in French, 1930), At the Villa Rose (1940). Also produced as a stage play (London, 1920).

A classic, as the Scribner’s paperback suggests? Consider the date it was first published, 1910, and here it is, back in print again. How many other books published in 1910 can you think of that you can say that about? And how many people of good taste must have read it by now? If it’s a classic, it will have had to have earned the title.

It is dated. If it were to be submitted to a publisher as newly written, there’s no doubt a revision would be demanded. Reading the first chapter relieves some fears, however — the symptoms of old age are there, but the book has not yet succumbed to the afflictions of rigor mortis.

In that first chapter, with precise pictorial writing, Mason described the first meeting of Mr. Ricardo with Mlle. Celie. She is on the verge of melancholy hysteria and despair outside a French casino; nest she is being soothed by the wealthy young English inventor, Mr. Wetherall.

On the very next night, Celie’s benefactress, whose companion she is, is robbed and murdered. The girl stands accused, at least of complicity. All the evidence, as well as the testimony of the maid, points directly to her. Nor does her background as a stage-variety spiritualist speak well on her behalf.

Mr. Wetherall asks that the famed M. Hanaud of the Paris Sûreté be called in. Hanaud is not only a gifted detective, but he is also a forerunner of all those other masterminds who know, or guess, and do not tell. Of course I know that Conan Doyle often allowed Holmes to lapse into this poor excuse for a storytelling device, but at least Holmes never insulted Watson, at least not directly, nor did he ever ridicule him for poorly asked questions, as Hanaud so badly treats Ricardo.

Speaking of whom — on pages 79-80 of the paperback edition Ricardo very nicely summarizes the eight salient features he sees in the mystery. Included in the replies Hanaud later makes to the questions that Ricardo happens to ask is one based on one of those very points. The latter (as a gentleman) accepts the rebuke when Hanaud loudly suggests that Ricardo has foolishly missed a vital point of the case.

The mystery is solved by page 145. The remainder of the books recounts that final version of the reconstructed crime, and Hanaud’s feeble attempt to explain the guesses in deduction that he made.

Well, as you can see, I was already biased. This may be too harsh a judgment, and by no account should you take this to mean that Hanaud’s version is impossible. It’s just that the facts, as described, I submit there is no reader who would have come to the same conclusion as Hanaud did by guesswork, pure and simple.

A classic? From a historical point of view, perhaps so. As a mystery, it’s an outdated one.They just don’t write them like this any more.

–Reprinted in slightly revised form from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 4, No. 5, Sept-Oct 1980.

Thu 7 Oct 2010

100 Important Books From Before the Golden Age —

David L. Vineyard

These are from the gray dawn of the origins of the genre up to 1913. Short story collections are included and a few novels that are only related (but closely) to the genre. They appear here in approximate chronological order, but not strictly so. Some books by an author are listed together even though they were published later.

My rule on these was simple. They had to fit within the dates and I had to have read them. The end date of 1913 marks the publication of Trent’s Last Case by E. C. Bentley, recognized as the beginning of the Golden Age. A few toward the end were not published in book form until after Bentley, but had been serialized before and so fit in the pre-Golden Age category.

Historians of the genre will note that Dickens was not writing detective stories and I agree, but many of these early books are direct progenitors of the detective novel as we know it and in their handling of crime and criminals important to the genre.

â— Captain Singleton by Daniel Defoe (the memoirs of a privateer, mostly the imagination of Defoe)

â— The Newgate Calendar by Anonymous (romanticized accounts of the likes of Dick Turpin, George Barrington, and Jonathan Wild)

â— Jonathan Wild by Henry Fielding (while the novel is satirical it could almost be a playbook for the career of Vidoq)

â— Caleb Williams by William Godwin (the first crime novel — and still a rousing tale of chase and pursuit as well as an early social reform novel)

â— The Romance of the Forest by Mrs. Radcliffe (many of the Gothic trappings used by the genre later on and all the supernatural is rationally — if not always logically — explained)

â— The Tales of Hoffman by E. T. A. Hoffman (he may actually predate Poe with the first detective story)

â— Rookwood by Hugh Ainsworth (most notable for the long section of the novel known as Dick Turpin’s Ride, a forerunner of Raffles, the Saint, and the gentlemen crooks)

â— The Bride of Lammermoor by Sir Walter Scott (a fictional account of an actual murder with some Gothic trappings, one of Scott’s Tales of the Landlord series)

â— Wieland by Charles Brockden-Brown

â— Confessions of an Unjustified Sinner by James Hogg (both this and Wieland are examples of the foundations of the psychological crime novel)

â— The Spy by James Fenimore Cooper (the story of one of Washington’s agents during the American Revolution)

â— The Memoirs of Vidoq by Eugene Francois Vidoq (non-fiction, more-or-less about the thief turned detective who gave us Dupin, Vautrin, Jean Valjean, Lecoq, and Sherlock Holmes as well as the modern police force as we know it — and the origin of ‘cherchez la femme’)

â— Tales of Mystery and Imagination by Edgar Allan Poe (no comment needed)

â— The House of Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne

â— Memoirs of a Bow Street Runner by Richardson (again non-fiction, more-or-less)

â— Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens (Fagin an early model for the criminal mastermind)

â— A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (international intrigue)

â— Bleak House by Charles Dickens (Inspector Bucket)

â— The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens

â— The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (the first and still one of the best detective novels)

â— The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins (Collins’ best book and with the wonderful villainy of Count Fosco)

â— Armadale by Wilkie Collins

â— No Hero by Wilkie Collins

â— John Devil by Paul Feval pere (the first Scotland Yard detective in Gregory Temple and an early prototype for Moriarity)

â— The Black Coats by Paul Feval pere (an early novel of organized crime)

â— The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas pere (all the mystery men in literature owe a debt to Edmund Dantes)

â— The Horror at Fontenay by Alexandre Dumas pere

â— The Mysteries of Paris by Eugene Sue (a huge crime novel by the Dickens of Paris)

â— The Wandering Jew by Eugene Sue (the use of a Tontine as a plot device and an early use of the reading of the will for dramatic purpose)

â— Les Miserables by Victor Hugo (politics, crime, injustice, Jean Valjean — yet another Vidoq figure — and the implacable Javert)

â— The History of the Thirteen by Honore de Balzac (Vidoq yet again, here as Vautrin)

â— Monsieur Lecoq by Emile Gabiorou (Gabiorou was Feval’s secretary and took the name of his hero from one of Feval’s villains — Lecoq is the most important figure between Dupin and Holmes)

â— Uncle Silas by J. Sheridan Le Fanu (still one of the seminal books in the genre)

â— Wylder’s Hand by J. Sheridan Le Fanu

â— The Leavenworth Case by Anna Katherine Greene (one of the classics and likely her best)

â— The Trail of the Serpent by Mary Elizabeth Braddon (splendid nonsense recently republished in a trade paperback edition with extensive notes and introduction)

â— Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume (helped to make the cab of the title the symbol of Victorian London — even though Hume is a colonial and a terrible writer)

â— The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson (most editions also include “Pavilion on the Links” and “The Sire De Maltroit’s Door,” both seminal to the genre)

â— The New Arabian Nights by Robert Louis Stevenson (virtually at the birth of the genre Stevenson is already poking fun at it)

â— The Wrong Box by Robert Louis Stevenson & Lloyd Osborne (humorous use of the Tontine plot beloved by the Victorians)

â— The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (again, no comment needed)

â— The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

â— The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

â— The Big Bow Mystery by Israel Zangwill (an early and great locked room)

â— The Chronicles of Martin Hewitt by Arthur Morrison (the first reaction against the colorful detective as represented by Holmes, and good in their own right)

â— The Hole in the Wall by Arthur Morrison (a fine crime novel worthy of Dickens or Stevenson)

â— As a Thief in the Night by E.W. Hornung (the first Raffles collection)

â— The Experiences of Loveday Brooke: Lady Detective by C. L. Pirkis (early female sleuth — if not the first — written by a woman)

â— The Shooting Party by Anton Chekov (Chekov’s only novel and it’s a murder mystery)

â— Hilda Wade by Grant Allen (completed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, an exceptional mystery of the chase and pursuit kind)

â— Pudd’nhead Wilson by Mark Twain (if not a detective story, good use of detectival skills)

â— The Old Man in the Corner by Baroness Orczy (still the best of the armchair sleuths and the final story still has a kick)

â— The Man in Gray by Baroness Orczy (an early example of the historical mystery)

â— Secrets of the Foreign Office by William Le Queux (spy stories featuring Duckworth Drew — fun in the right mood)

â— The Count’s Chauffeur by William LeQueux (an early and influential use of the automobile in crime fiction)

â— The Innocence of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (first and best of the paradoxical priest)

â— The Secrets of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (ironically these were written almost twenty years before Chesterton became a Catholic in 1922)

â— The Man Who Was Thursday by G. K. Chesterton (the detective novel as parable and allegory)

â— My Adventure on the Flying Scotsman by Eden Phillipotts ( a novella really — Phillipotts is important both on his own — The Red Redmaynes — and because he encouraged young Agatha Christie to keep writing)

â— The Passenger From Scotland Yard by Henry Wood (murder, smuggling, and trains)

â— The Great Tontine by Hawley Smart (one of the best of uses of the Tontine plot) [1]

â— The Rome Express by Major Arthur Griffith (this helped to popularize the idea of intrigue on a train) [1]

â— Mr. Meeson’s Will by H. Rider Haggard (a mix of adventure story and trial novel with a somewhat racy finale)

â— The Red Thumb Mark by R. Austin Freeman (no sooner had fingerprints been accepted as evidence in court than Freeman proved they could be forged — not unlike the detective work that would break the real Sir Harry Oakes case in 1943 in the Bahamas)

â— The Singing Bone by R. Austin Freeman (the invention of the inverted detective story, the most important innovation since Holmes)

â— John Silence by Algernon Blackwood (the finest of the psychic detectives, everyone a classic — you may never look at cats or French villages the same again)

â— November Joe by Hesketh Prichard (fine tec tales of a Canadian half-breed trapper)

â— The Eyes of Max Carrados by Ernest Bramah (Carrados is a bit of a superman, but these are still great reading)

â— The Prisoner of Zenda by Anthony Hope (prototype for a thousand books of international intrigue to come)

â— The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings by L.T. Meade & Robert Eustace (an international criminal conspiracy not unlike those so popular today)

â— The Exploits of Valmont by Robert Barr (highly entertaining stories and an early forerunner of Poirot)

â— The Gentle Grafter by O. Henry (clever stories about charming con man Jeff Peters)

â— The Beetle by Richard Marsh (a mix of horror and detective story, in many ways second only to Dracula for genuine chills) [1]

â— Dr. Nikola by Guy Boothby (the Italian Peril and great fun, Nikola one of the great villains in the literature)

â— The London Adventures of Mr. Collin by Frank Heller (Philip ‘Flip’ Collin is the Danish Raffles)

â— Carnaki, Ghost Finder by William Hope Hodgson (supernatural sleuth and some real chills)

â— The Thinking Machine by Jacques Futrelle (Futrelle of course perished on the Titanic, but luckily there are two good collections of this series)

â— Cleek, the Man With Forty Faces by Thomas Hanshew ( a great favorite of John Dickson Carr with an penchant for impossible crimes almost as impossible as the hero, but fun in the right mood and who can resist a Scotland Yard man named Maverick Narcom?)

â— The Man in Lower 10 by Mary Roberts Rinehart (this was serialized before The Circular Staircase was published — my own choice as her best)

â— Kim by Rudyard Kipling (granddaddy of the Great Game)

â— In the Fog by Richard Harding Davis (too little read today, a splendid little book, and be sure to get the edition with the color plates by Frederic Dorr Steele) [1]

â— At the Villa Rose by A. E. W. Mason (without Hanaud there is no Poirot)

â— The Exploits of Arsene Lupin by Maurice Leblanc (the French Raffles and in much of the world a rival to Holmes himself)

â— 813 by Maurice Leblanc (Lupin’s greatest case in which is client is the Kaiser)

â— The Mystery of the Yellow Room by Gaston Leroux (one of the great locked room tales of all time)

â— The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux

â— Stories of the Railroad by Victor L. Whitechurch (these tales of Thorpe Hazel are some of the best short detective stories of their era)

â— Uncle Abner: Master of Mysteries by Melville Davidson Post (the finest collection of American detective stories since Poe)

â— The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason by Melville Davidson Post (Perry’s last name is no coincidence)

â— Ashton Kirk Investigator by John McIntyre (McIntyre went on to become a serious novelist about gangsters; A-K also features in Ashton Kirk Secret Agent and others)

â— Prince Zaleski by M. P. Shiel (the last gasp of the Decadent era — unique is plot and execution)

â— The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad (the first serious novel about terrorism)

â— The Four Just Men by Edgar Wallace (the birth of the modern thriller)

â— The Romance of Terence O’Rourke, Gentleman Adventurer by Louis Joseph Vance

â— The Lone Wolf by Louis Joseph Vance (Vance’s Michael Lanyard would become the standard for most the gentleman crooks to come, and his adventures are still worth reading)

â— The Achievements of Luther Trant by Edwin Balmer & William McHarg (perhaps the first psychological sleuth)

â— The Power House by John Buchan (Graham Greene calls it the first modern spy novel)

â— The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu by Sax Rohmer (say what you will — I love it — one of the most influential books in the genre — Racist? Yes, the Anglo-Saxons are all idiots as S. J. Perlman pointed out)

â— The Silent Bullet by Arthur B. Reeve (the introduction of Craig Kennedy the Scientific Detective, dated, but these stories show some energy)

â— The Great Impersonation by E. Phillips Oppenheim (the last of the great Edwardian spy novels, within the next year both The Thirty Nine Steps and Riddle of the Sands would leave if forever behind)

â— The Lodger by Mrs. Belloc Lowdnes (the classic novel of Jack the Ripper)

â— Fantomas by Marcel Allain & Pierre Souvestre (the newspaper serialization barely squeezes in — the surreal criminal Fantomas is unique in the genre)

[1] The Great Tontine by Hawley Smart, The Rome Express by Major Arthur Griffith, In the Fog by Richard Harding Davis, and The Beetle by Richard Marsh, are all collected in one volume as Victorian Villainies edited by Graham and Hugh Greene