Search Results for 'Julian Symons'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 22 Sep 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

JULIAN SYMONS – Playing Happy Families. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1995; paperback, 1995.

Though I’ve read a good bit of Julian Symons’ criticism — enough to know that we had quite different tastes and attitudes — to my memory, I haven’t read any of his fiction.

The Midway family is a happy family. John and Eleanor are celebrating 30 years of marriage, and the family has gathered in their honor. Giles, John’s brother, High Court justice; Eversley, Eleanor’s son by a previous marriage, and his wife and children; son David and his wife; and daughter Jenny.

This is the last time they will play happy families, though, because in the next week Jenny will vanish. In the aftermath all of them will learn much of themselves, and each other. Detective Superintendent Hilary Catchpole must try to learn where Jenny is, and what happened to her. None of them will enjoy their lessons.

There is a type of crime novel, not peculiar to British crime-writers but certainly one of their favorites, wherein detection is less, or at least no more, the focus than are the effects if a crime in a group of people. That’s the sort of book this is, and of the type it’s quite well done.

Symons is a smooth and literate writer, and more than adept at characterization. My problem with it is the same one I have with much of Ruth Rendell’s work. I don’t particularly enjoy looking at an album full of pictures of sad and ugly people, no matter the skill of the photographer.

Only the lead police detective here is even remotely sympathetic, and one gets the feeling that Symons doesn’t care for him too much. Well done, but to me not very enjoyable.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #17, January 1995.

Bibliographic Note: Supt. Hilary Catchpole made a second and final appearance in A Sort of Virtue (Macmillan, UK, 1996; no US edition).

Tue 9 Nov 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

REVIEWED BY JEFF MEYERSON:

JULIAN SYMONS – A Three Pipe Problem. Harper & Row, US, hardcover, 1975. Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1975. Reprints include: Avon, US, pb, 1976; Penguin, US, pb, 1984.

A Three-Pipe Problem is a very enjoyable book! Symons’ hero is Sheridan Haynes (nicknamed Sher), an actor who portrays Sherlock Holmes in a British TV series that was once popular but is now slipping in the ratings.

Sher demands absolute fidelity to the Holmes stories, which angers those who want to make the show more attractive to the audience by adding a love interest, etc.

Haynes not only longs for the days when Holmes stalked London, but has even insisted on living in the old rooms in Baker street. His obsession with Holmes causes doubts about his sanity, and problems with his wife and co-workers.

Haynes, in his role of Holmes, becomes gradually more involved in a case known as the Karate Killings, to the consternation of all. He states that Sherlock Holmes could have solved the case, then sets out to do it with the help of a Watson, and some Baker Street Irregulars (actually Traffic Wardens).

Symons keeps the various strands of his story well in hand until they all come together on a cold and foggy London night, with Haynes/Holmes tracking the Karate Killer.

Sher Haynes is a sympathetic character and the book, if improbable, is a lot of fun and very well done. Sherlockians should enjoy it.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 1, No. 3, May 1977.

Bibliographic Note: Sheridan Haynes made an encore appearance The Kentish Manor Murders (Viking, 1988).

Tue 16 Jun 2009

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

JULIAN SYMONS – The Broken Penny. Victor Gollancz, UK. hardcover, 1953. Harper & Bros., US, hc, 1953*. US paperback reprints include: Dolphin C227, 1960; Beagle, 1971; Perennial Library P480, 1980; Carroll & Graf, 1988*. (* = shown)

Many writers of espionage are content to rely on newspaper stories thinly disguised as fiction, with terrorism and hijacking their stock in trade. Though The Broken Penny (1953), recently reprinted by Carroll and Graf, is flawed, it remains a much more imaginative cold-war thriller.

Telling of the attempt to oust the communist government of a country never named, but apparently based on Poland, Symons provides a devastating picture of people under the totalitarian yoke, but he saves some room to show Britain and the British army in what is not their finest hour.

There is suspense, but mostly The Broken Penny is about the attempt of its protagonist to maintain his Idealism in a world that had gone mad in the early 1950s — and isn’t much saner as I write these words.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988 (very slightly revised).

[EDITORIAL COMMENT.] The fellow in the cover of the Carroll & Graf paperback edition looks a lot like Henry Fonda to me. The girl looks familiar as well, but I can’t put a name to the face. This is rather surprising, as there never was a film version of The Broken Penny.

In fact, and what’s even more surprising, is that according to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, of all the mystery novels that Julian Symons wrote, only one of them has ever been made into a movie, that one being The Narrowing Circle (1954; film, 1955).

The detective in that book was Inspector Crambo, who also appeared in The Gigantic Shadow (1958, published in the US as The Pipe Dream). According to IMDB, Trevor Reid played Inspector ‘Dumb’ Crambo in The Narrowing Circle, which also featured Paul Carpenter, Hazel Court and Russell Napier. (And if Hazel Court is in it, then it’s a must find.)

Included in the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, a series episode of Kraft Suspense Theater entitled “Twixt the Cup and the Lip” was based on a short story in the collection How to Trap a Crook and 12 Other Mysteries.

But it looks as though I’ll have to tell Al Hubin about this: According to IMDB, the following Symons novels were also turned to movies:

Criss Cross Code (*) as Counterspy.

The Man Who Killed Himself as Arthur! Arthur!

The Blackheath Poisonings, as a 3-part miniseries.

[??] as Die Spur führt ins Verderben. (**)

(*) This is not a novel, but a perhaps uncollected novelette first published in Lilliput, Aug-Sept 1951. (**) According to Babel Fish, a direct translation is “The trace leads into spoiling.”

[UPDATE] 06-17-09. Al Hubin has agreed that items 2 and 3 should be in CFIV, and the first also, but only if “Criss Cross Code” appeared in a Symons story collection, perhaps in retitled form.

Also, in the comments, Steve W. has pointed out that The Thirty-First of February “was made into what I remember to be a quite good episode of the Alfred Hitchcock Hour.”

True. It was, and I missed it when I was researching Symons on IMDB last night. Date: 4 January 1963, and as Steve advised me in a followup email, “the whole season is available at Hulu. Here’s the link to the Symons adaptation: HULU: 31st of February.”

So far, I’ve managed to stay away from Hulu. I spend too much time at the computer as it is, and to start watching TV here at my desk might mean never getting anything done. Nonetheless, there might be a possibility of exceptions being made. Maybe now and then?

Sat 14 Jun 2008

JULIAN SYMONS – Bogue’s Fortune.

Perennial Library; paperback reprint, 1980. Harper & Brothers, US, hc, 1957. Other US paperback editions under this title: Dolphin, 1961; Carroll & Graf, 1988, 1993. First published in the UK as The Paper Chase: Collins Crime Club, hc, 1956. Paperback reprints under this title: Fontana, UK, 1958, 1966; Corgi, UK, 1970; Beagle, US, 1971.

This is the book I began reading immediately after I finished The India-Rubber Men, by Edgar Wallace, and reviewed here not too long ago. It is also the book that I contrasted the Wallace book to in the comments that followed, saying:

“But after I finished writing up my review of the Edgar Wallace book, I started one by Julian Symons. The difference between the two — well, what comes to mind first, it’s like comparing night with day, or very nearly so.

“Symons’ story is witty and clever, and filled with engaging people — some of whom are obviously wrong-intentioned or have taken wrong turns in their life — but still engaging. The story line is filled with puzzling events that make me (the reader) want to keep reading to see what comes next, and this is the test where I think The India-Rubber Men comes up short, or at least it did with me.

“(So far I’ve only just begun Symons’ book, but neither did I turn out the light on it when it got late last night, as I did a number of times with the one by Wallace.)”

I confess that I got sidetracked in reading Bogue’s Fortune – since the time I started the book and now, my wife and I have been watching the entire 13-episode season of Eli Stone on DVD, not crime-related but we both think it’s a fabulous show. But I finished the book in one last gulp last night, closing the pages around 2 a.m., and now here I am and ready to report.

Don’t expect a long analysis of all of Symons’ work, however, or any, for that matter. This is the first one I can recall ever having read, but no matter if it’s typical of his crime fiction – and I suspect not – it will not be my last.

He was in thriller mode when he wrote this one – which is what brought up the comparison with Edgar Wallace in the first place – and I’m sticking with my original impression. It’s witty and clever, and filled with engaging people, as I said earlier.

The story – at least he’s getting to it, you say, and I am – begins with a chap named Charles Applegate about to embark on a new career, that of instructor at Bramley, an ultra-progressive school for delinquent children somewhere outside of London. He has an ulterior motive, as he is no teacher, only a detective story writer looking to place his next mystery in such an establishment.

After some hugger-mugger on the train down, his first night at the school is marred by the discovery of his also newly-arrived colleague dead in the victim’s own bed in the room next door. Murder it is, committed with the knife that Applegate took from one of the students around meal time the evening before.

This all in the first 50 pages, and by page 72 he is having the following conversation with Hedda Pont, the young matron of the school and the niece of the director. She is as equally progressive as the school, which of course part of her charm to Applegate:

“I hope you’re not going to the police,” she said.

“The police.” Applegate was quite disconcerted. “Do you know, that never occurred to me. I should have rather a lot of explaining to do.”

“That’s wonderful. Let’s do some investigating on our own.” Her blue eyes were bright as tinsel. Was it significant, Applegate wondered, that this should be the simile that occurred to him?

Not surprisingly, perhaps, it is Hedda who has a better head on her shoulders for detecting than does Applegate, and perhaps even more physically active in the case that follows as well. One begins to think that Symons is being a bit satirical here, and once started thinking in this direction, one cannot begin to stop. Nor should one, and the way the ending plays out will only reinforce that thought.

I do not think that Symons was thinking so much of Wallace when he write this, however, and while I am also not so very familiar with John Buchan, the latter’s name is invoked on page 135, in the following conversation that closes Chapter 16:

“Good night.” He turned out the light.

“Do you know the most fascinating thing of all?” Her voice came from the darkness.

“What’s that?”

“The face peering from the tower. And the man with the lobe missing off his ear. Positively too John Buchan for words.”

Don’t get the wrong idea from the first sentence in that last selection. Hedda’s previous sentence had been, “A girl just can’t be ardent all the time. Will you turn out the light? Good night.”

While both the beginning and end of this thriller adventure, combined with a little bit of detection, meet my prior expectations and then some, the middle sags a little, beginning with a 20 page exposition of the facts of the matter by one of the participants on the adversarial side, or at least his version of them, and no, it is not really known for a while whose side he is on, besides his own, and the jury may safely disregard this entire remark – or at least the second half of it.

The overall rating, then, if I were to give one, still averages out to much better than average. Much. (And if you were to ask, I would have to say that the US title is the better one. By far.)

Tue 2 Apr 2024

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS PI Review

by Robert E. Briney

STANLEY ELLIN – The Specialty of the House and Other Stories: The Complete Mystery Tales, 1948-1978. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1979.

Stanley Ellin made his first impact on the mystery field as a writer of short stories; and in spite of more than a dozen highly praised novels, it is still as a short-story writer that many readers think of him. This hefty collection contains, in chronological order, all thirty-live of the stories written during the first thirty years of his writing career. All but one of them originally appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, where the author’s “annual story” is still an eagerly awaited event. The first seven stories in the collection, starting with the title story (surely one of the most impressive debuts in the field), were prizewinners in the annual Ellery Queen contests.

Here we have “The Betrayers,” in which a young man constructs an air-tight solution to the wrong crime; the Edgar-winning fantasy “The House Party”; a second Edgar winner, “The Blessington Method,” with its unique approach to gerontology; “You Can’t Be a Little Girl All Your Life,” the story of a rape and its aftermath; “The Crime of Ezechicle Coen,” with its roots going back to the German occupation of Rome in World War II; “The Twelfth Statue,” a novelette of murder in a Rome film studio; “The Corruption of Officer Avakadian,” concerning doctors who ref use to make house calls; and “The Question,” in which the whole point of the story is compressed into a single devastating three-letter word in the final sentence. The stories vary widely in theme and setting. but exhibit the same polished craftsmanship.

In his introduction to the volume, speaking of another master of the short story, Guy de Maupassant, Ellin wrote: “Here was a writer who reduced stories to their absolute essence. And the ending of each story, however unpredictable, was, when I thought of it, as inevitable as doom.”

These words might have been written about Ellin’s own work. When Ellin’s first ten stories were issued in book form under the title Mystery Stories in 1956, the book was praised by Julian Symons as “the finest collection of stories in the crime form published in the past half-century.” With the addition of twenty-five stories and twenty years, the judgment still stands.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 26 Dec 2023

REVIEWED BY MIKE TOONEY:

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Autumn 2023. Issue #64. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: The White Elephant Mystery by Ellery Queen, Jr.

If you like detective fiction in any or all of its permutations then you can’t go wrong with Old-Time Detection. The new mingles with the old (which means, in most cases, the classic), leaving plenty for the reader to feast on.

Among the delectations: an interview with a science fiction/fantasy/detective story author; plenty of well-researched background on the creator of the world’s most famous criminal lawyer; the latest (at the time) paperback reprints from the seventies; a review of a collection of stories by the master of noir; a long-lost Dr. Poggioli story and a witty and amusing self-assessment by its author; a view of the “master conjurer” of fair play detection and a look at how he lived; news about the creator of Poirot and Marple and how the current generation is handling (and, in too many cases, mishandling) her works; a glance at how today’s publishers seem to be on some sort of nostalgia kick, which is good news for detec-fic aficionados; words about the undisputed “king of the classical whodunit”; and the editor’s appraisal of a kids’ novel that even adults can enjoy.

In it you will find:

(1) A 1976 interview with Isaac Asimov in EQMM: “I was the comic relief …”

(2) Francis M. Nevins gives us the first part of a multipart essay (2010) about Erle Stanley Gardner; however: “Those wishing to read about Gardner’s Perry Mason character must wait for Part Two.”

(3) Charles Shibuk continues his summary (1973) of the “paperback revolution” in detective/mystery publishing that was occurring half a century ago, focusing on Margery Allingham, Agatha Christie, Amanda Cross, Carter Dickson (otherwise JDC), Erle Stanley Gardner, Frank Gruber, Ngaio Marsh, Bill Pronzini, Rex Stout, Julian Symons, and Charles Williams.

(4) This is followed by Shibuk’s review (1975) of Nightwebs (1971), a collection of Cornell Woolrich’s “mainly unfamiliar works,” edited by Francis M. Nevins, Jr.: “Some of these stories are of extremely high quality, but alas, there is also much dross.”

(5) The issue’s centerpiece story is T. S. Stribling’s “The Mystery of the Paper Wad” (EQMM, 1946), which hasn’t been seen generally since first publication, followed by Stribling’s own “The Autobiography of an Ingenious Author” (1932): “The criminologist smiled at the illusion held by every man that with him all things, crimes and virtues, are possible.”

(6) In “The Full Mandrake” (2023), Rupert Holmes offers us “an appreciation of John Dickson Carr”: “If the classic fair play detective story is the magic act of literature, then John Dickson Carr is forever its master conjurer . . .”

(7) Douglas G. Greene’s assessment (1995) of JDC’s A Graveyard To Let (1949) (“. . . still, the swimming-pool gimmick is beautifully handled”), as well as Carr’s lifestyle as a New Yorker: “While he wrote in his attic study, Carr smoked continuously and tossed the cigarette butts on uncarpeted parts of the floor . . .”

(8) Dr. John Curran’s “Christie Corner” (2023) looks at what’s happening to AC’s heritage and finds all is not well, warning us about one project: “AVOID IT AT ALL COSTS.”

(9) Michael Dirda’s survey of the current scene, “Classical Mysteries Are Having a Moment” (2023): “. . . for devotees of old-time detection, recent publishing does seem surprisingly retrospective, even nostalgic.”

(10) Jon L. Breen’s article “Edward D. Hoch: King of the Classical Whodunit” (2008): “He practiced the increasingly lost art of the classical detective short story better than all but a handful of writers in the history of the genre.”

(11) There’s a mini-review of The White Elephant Mystery (1950) by Arthur Vidro: “It’s well-plotted and well-written . . .”

(12) As usual there’s a puzzle (and it’s a dilly).

(13) The issue ends with the sad news of Marvin Lachman’s passing: “Without Marv, we [at OTD] would have lacked the participation of leading professionals.”

____

Subscription information:

Published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S.: $18.00. – One-year overseas: $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros). – Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal. – Mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743.

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net

Fri 30 Sep 2022

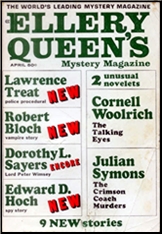

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE April 1967. Overall rating: ***

JULIAN SYMONS “The Crimson Coach Murders.†Novelette. First published in The Evening Standard, 1960, as “The Summer Holiday Murders.” A detective story writer seeking background material takes a tour through southern England. Murder gives him a chance to try his abilities. (3)

ROBERT BLOCH “The Living Dead.†A World War II vampire story; not too imaginative. (2)

EDWARD D. HOCH “The Spy Who Came Out of the Night.†Rand of Double-C is sent to Berne to decode a message. His bitterness is forced to light. (3)

JACQUELINE CUTLIP “The Trouble of Murder.†A murderer burns down his inheritance unknowingly. Dry and confusing writing, but ending is good. (4)

CORNELL WOOLRICH “The Talking Eyes.†Novelette. First published in Dime Detective Magazine, September 1939, as “The Case of the Talking Eyes.†A paralyzed woman, able to communicate only wth her eyes, overhears her son’s wife plotting to kill him. Unable to stop the murder, she manages to avenge his death. Who else could attempt such a story? (4)

RHODA LYS STOREY “Sir Ordwey Views the Body.†Anagram-pastiche [by Norma Schier] of [Dorothy L. Sayers’] Lord Peter Wimsey. (1)

DOROTHY L. SAYERS “The Queen’s Square.†First appeared in The Radio Times, December 23, 1932. Lord Peter Wimsey solves a murder no one could have committed. A red costume in red light would appear white. (3)

JIM THOMPSON “Exactly What Happened.†Man disguised as another is killed by the other disguised as him. (1)

H. R. WAKEFIELD “The Voice of the Inner Ear.†First appeared in The Clock Strikes Twelve by H. Russell Wakefield, Herbert Jenkins, 1940, as “I Recognised the Voice.†A “psychic†detective solves mysteries. (2)

L. J. BEESTON “Melodramatic Interlude.†Revenge is thwarted by the victim’s wife. Obvious but still exciting. (3)

CHRISTOPHER ANVIL “ The Problem Solver and the Burned Letter.†Richard Verner reads a clue from a typewriter ribbon. (2)

LAWRENCE TREAT “P As in Payoff.†Mitch Taylor of Homicide Squad solves a hotel robbery as he tries to gain a favor. (3)

–January 1968

Sat 25 Sep 2021

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

COLIN WATSON – Snobbery with Violence: Crime Stories and Their Audience. Eyre & Spottiswoode, UK, hardcover, 1971. St. Martin’s Press, US, hardcover, 1972. Eyre Methuen, UK, hardcover, revised edition, 1979. Mysterious Press, US, softcover, 1988 Faber and Faber, UK, paperback, 2009.

I could never quite understand why one of my favorite books about the crime genre incited such violence in some readers, who bore a grudge against Watson for his informed and informing book on mystery and thriller fiction between the Wars that seemed completely out of proportion to anything he actually wrote.

Watson, after all, was the popular author of the Flaxborough/Inspector Purbright novels that revealed the darkly comical reality beneath the English village setting of Agatha Christie and others.

Yes, he was opinionated. Even I disagree with him on some points and authors, but he is never less than succinct in his arguments, and there is no malice in them. He merely sets out to deal with the social history behind the genre in that important era and to explain its origins and nature, and does so brilliantly, with delightful cartoons from Punch, that reflect the subject of many chapters.

If nothing else he coined a phrase to describe the village mystery so common to Agatha Christie that has stuck because it is so apt: Mayhem Parva.

Julian Symons’ Mortal Consequences seemed much more controversial to me, Kingley Amis’s James Bond Dossier more eccentric. Just what nerve had Watson struck?

The book opens with an epigram from Alan Bennett’s Forty Years On: “…that school of Snobbery with Violence that runs like a thread of good class tweed through twentieth-century literature.â€

Snobbery with violence hardly seems an unfair description of the genre from Agatha Christie to Bulldog Drummond, and indeed to James Bond who Watson defends from the charge of “sex, snobbery, and sadism†by simply pointing out Ian Fleming was no more blatant nor vicious on that count than anyone else.

So what is it exactly about this well organized and argued book that upset so many. I confess on rereading I was trying pretty desperately to discover that when I ran across the following passage on Bulldog Drummond, Sapper, and the rise of Fascism in England.

Popular fiction is not evangelistic; it imparts no new ideas. Fascism sprang, in Britain as elsewhere, from frustration caused by economic chaos and political ineptitude. That same frustration had made readers susceptible to improbable heroics, but acknowledgement of a common source is not the same as saying Moseley’s Fascism derived from McNeile’s fiction.

And there it was, the passage that set forth Watson’s “controversial†theme that inflamed what Amis once called “little old maids of both sexesâ€, the thing that enraged many of his critics. Watson had dared to suggest that popular fiction, far from the monster poisoning the minds of readers, was not actually the source of all societies ills, but merely reflected the prejudice and opinions of the average man, that people indeed got the entertainment they wanted and would accept in popular fiction, and were not swayed to prejudice by the blathering of a Bulldog Drummond or to snobbery by a Lord Peter Wimsey, nor to sexual obsession by James Bond, but that H. C. McNeile, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Ian Fleming were merely highly successful at hitting on what the audience wanted and would accept at the time.

An audience that, as he quotes Margaret Lane Edgar Wallace’s biographer, audiences wanted “excitement without anxiety, suspense without fear, violence without pain, and horror without disgust,†to which Watson added crime without sin and sentiment without sex.

If there is a better description of the mystery novel and thriller in the between the Wars years, I don’t know what it is. He goes on to point out that the reader was an active participant in the game being played, not ignorant of reality enough to buy the sophistication of an Oppeheim drawing room or casino or a Christie great house where a murder will soon occur, but “able to disregard the voice of experience and reason in interest of his own entertainment.â€

In short the reader was not being plied with clever drugs, but willingly seeking the stuff out, rewarding a Sax Rohmer who confirmed his own fear of foreigners and foreign sorts, a Sapper or Sidney Horler catering to the average man’s self doubts with their “splendid†sportsman manly man heroes and slim topping women pitted against wealthy unsporting master criminals, slinky foreign women, inscrutable Easterners, and low East End types. The writers weren’t even prostituting themselves, they had merely stuck upon a gold vein of public prejudice and opinion.

This was the era of the lending library and the newly literate middle and lower middle classes equally prejudiced against the very rich, the foreign, and the poor. The era in England when an entire generation of young vital men had died in the trenches in Europe and the world no longer made sense and people were desperate to make sense of it. The writers who succeeded, who prospered were not preaching, but merely reflecting, and the more accurately they reflected their audience the more successful they were, and when they could do so with minimal disturbance of the social order they were rewarded.

Watson touches on the strangely clipped and emotionless language of the era, the blathering of a Drummond, Wimsey, or Campion, the topping girls, the sometimes silly language, even the bloodless violence.

Many of course had been through the 1914-1918 war themselves. What seems to a later generation to be a slightly comic affectation might well have been a defensive mannerism born of an experience so appalling that it rendered millions emotionally emasculated.

Again, the audience and not the writers determined the voice. The sheep were not led, but leading because to go against the prejudice of the flock was to risk a blow to the pocketbook. “Foreign was synonymous with criminal in nine novels out of ten, and the conclusion is inescapable that most people found that perfectly natural.â€

What Watson is saying that really hits home is that when we are condemning a popular writer like Rohmer, Horler, Sapper, or Edgar Wallace we are actually condemning grandpa and grandma or mom and dad, who read this because they believed this, not because they were being force fed prejudices they had not been schooled in well before they read thriller fiction.

The same was true of Ian Fleming, of Mickey Spillane, of Stephen King, or Lee Child today. We get the popular literature, the movies, the music we support that reflects what we believe and what we value. Pretending we are led down the garden path by what we consume is like blaming the apple tree because some of the apples aren’t ripe yet.

Charging commercial institutions with failing to educate the public taste is an indulgence from which intellectuals (*) will only be deterred when they grasp that a non-existent contract can neither be breached nor enforced. If commerce is to be indicted for anything, it can only be for commercialism, and whether that is a crime or not is a political question.

Watson also makes a good argument for the value of this kind of fiction which, as he points out, reflects the material life of its time in a way more serious literature does not down to the smallest detail of daily life in its need to be grounded in recognizable worlds familiar to the less than sophisticated reader. He also points out that during the heyday of the lending library readers had something like 180 to 210 books a week to choose from across all genres, but certainly in the mystery genre. Even figuring a reader reading one book a week the competition was fierce for the reading dollar. Readers, not writers dictated what was acceptable in their chosen reading with their money.

I’ll leave with Watson at his most cogent. If you disagree with this conclusion, and I don’t discount any disagreement, please quote a single legally and psychologically proven case and not apocryphal accusations or criminals and their representatives seeking an out by unfounded claims of victimhood is all I ask.

The influence of books is of a more subtle and involved nature. The most lasting, and therefore the most serious, harm they can do is to confirm — to lend authority to, as it were — an existing prejudice or misconception. During the long and lively discussion of the influence of “undesirable†literature upon behavior, there has come to light not a single case in which a formerly normal person (my italics) has been induced by his reading to commit a violent crime.

—

(*) Intellectual in England does not only connote the Left alone. There are equally those on the Right condemning the taste of the “common man†and the Middle Class.

Sat 11 Sep 2021

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Thomas Baird

EDMUND CRISPIN – The Glimpses of the Moon. Gervase Fen #10 (of 11, including two collections). Gollancz, UK, hardcover, 1977, Walker, US, hardcover, 1978.

Gervase Fen, Oxford professor of English language and literature, who it seems spends more time being detective than don, is the creation of Edmund Crispin, who in actual fact is Robert Bruce Montgomery. Montgomery was an organist, choral-music composer, and wrote background music for many movies. Humorous passages about the plight of composers and musicians appear in some of the Fen adventures in major and minor keys.

The Fen tales are academic (with Latin quotations and private jokes) but markedly satirical, and sometimes tumble into farce. Julian Symons said that “at his weakest he is flippant, at his best he is witty.”

Fen is energetic, even frenetic, and when he gets going on the case, the narrative zips right along. If you like humor mixed with your crime, then all nine Gervase Fen novels will be of interest.

Two collections of short stories have also been praised, but they are not as good as the novels. They are fair but flat, dependent on gimmicks, and Fen doesn’t really have room to operate.

In The Glimpses of the Moon, Fen is on sabbatical from Oxford to write the book on the postwar British novel, and is not particularly interested in hearing about a two-month old murder that the police had handily solved, getting their man. Fen’s interest in the case is finally piqued when the second dismembered body is discovered and he realizes the head he has been toting about in a potato sack is the wrong one (of three).

Beneath an apple tree where Fen is perched, the situation comes to a head in the pandemonious collision of a hunt, hunt saboteurs, a motorcycle scramble, a burglar’s getaway, a herd of cattle driven to pasture, a scouting helicopter, and police hurrying to arrest a miscreant. The fun almost pushes the investigation into the back seat.

Crispin writes excellent set-piece scenes where the characters make exhibitions of themselves, and Glimpses is peopled by a superabundance of eccentrics: A retired cavalry man who loathes horses, a failed foreign correspondent, an anti-popish rector in drag, a gray bureaucrat from the power board, a laconic rustic, a mad-scientist pathologist, a reclusive publican, a horror-movie-music composer, a brooding pig farmer and his nymphomaniac wife, lively and deadly policemen, even an electric power pylon come to life — all set against a background of tranquil village life in peaceful Devon.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 26 Jul 2021

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE. January 1967. Overall rating: 3½ stars.

HUGH PENTECOST “Volcano in the Mind.†Short novel. Dr. John Smith. First appeared in The American Magazine, December 1945, as “Volcano.â€

Dr. John Smith, an unobtrusive psychiatrist-detective, stops a clever murderer who is trying to drive a man to kill his wife, thus disposing of them both. Smith is very perceptive in his quiet way, but the story may be just a little dry. ****½

Bibliographic Update: Dr. John Smith appeared in three novellas in The American Magazine (collected in Memory of Murder, Ziff-Davis, 1947), one short story in EQMM, and two novels.

JULIAN SYMONS “The Santa Claus Club.†Francis Quarles. 1st US publication. Previously published in Suspense, UK, December 1960. A threatening letter typed on one of only 300 possible machines; a club where all dress up like Santa. The grand ’tec tradition? (2)

KENNETH MOORE “Protection.†An outsider wants some of the Orleans Street District action but needs protection. (3)

TALMAGE POWELL “Last Run of the Night.†A bus-driver is a killer. Obvious. (2)

HAROLD R. DANIELS “Deception Day.†A man commits a perfect murder in killing his shrewish wife. It’s too bad that justice, or conscience, had to win out. (4)

MICHAEL HARRISON “The Mystery of the Gilded Cheval-Glass.†A “hitherto unpublished†story of C. Auguste Dupin, who saves an artist from arrest by deciphering a dying ma’s last words. Let’s leave it for Poe enthusiasts. (2)

ROBERT McNEAR “The Salad Maker.†Mystery of the Absurd. That’s the right word. (1)

JAMES HOLDING “The New Zealand Bird Mystery.†The two authors of the Leroy King stories use a small scrap of writing for their deductions in solving a shipboard murder. (3)

BERNARD J. CURRAN “The Mysterious Mr Zora.†First story. Would 94,600 people not notice an extra 10¢ charge on their checking account? (1)

ELLERY QUEEN “Last Man to Die.†Reprinted from This Week, November 3 1963. Also published in the June 2004 issue of EQMM. QBI: Intelligence Department. A butlers’ club forms a tontine, the outcome of which EQ must decide. Not difficult. (3)

MICHAEL GILBERT “A Gathering of Eagles.†Previously published in Argosy (UK) January 1966, as “Heilige Nacht.†Calder and Behrens are called to Bonn to complete a cold-war breakthrough in Intelligence. Fast-moving and exciting. (4)

CHARLOTTE ARMSTRONG “The Cool Ones.†A grandmother’s quick thinking gives her grandson the clue to the location of her kidnappers. (3)

–September 1967