Search Results for 'R A J Walling'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 20 Mar 2011

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

R. A. J. WALLING – Marooned with Murder. Morrow, hardcover, 1937. UK edition published as Bury Him Deeper, Hodder & Stoughton, hc, 1937.

R. A. J. Walling, a British journalist and newspaper editor who began writing mysteries as a hobby in his late fifties, received a good deal of acclaim during his time. (His first book was published in 1927, his last posthumously in 1949.)

The New York Times stated in 1936 that Walling had considerable skill in weaving mystery plots; the Saturday Review of Literature decided that he wrote suavely baffling stories; the eminent critic Will Cuppy said of one of his early novels that it was “absolutely required reading.”

This reviewer couldn’t agree less.

In the first place, Walling wrote some of the dullest mysteries ever committed to paper; it may even be said that he elevated dullness to a fine art. And in the second place, his series sleuth, private inquiry agent Philip Tolefree, is a twit.

He says things like, “You’re a vandal, Pierce. You’ve feloniously broken into my ivory tower. Never mind. I’d have been bored in another half hour. How’d you find me out? Sit down, my dear fellow. Cigarette? Pipe? Well, carry on. What’s the trouble now? Or did you come for the sake of my beautiful eyes?”

He is also fond of quoting obscure Latin phrases, treating his sometime Watson, Farrar, as if he were an idiot, and withholding information from everyone including the reader.

Although Tolefree operates out of a London apartment, most of his cases seem to take him into the countryside. He solves them in the accepted Sherlockian manner of detection and deduction, using an inexhaustible fund of knowledge both esoteric and ephemeral.

Another reason he is so successful at unmasking murderers is his familiarity with such matters and motives as skeletons in closets, hidden relationships, peculiar wills, strange disappearances, and Nazi infiltrators, since nearly all his investigations seem to uncover one or any combination of these.

Marooned with Murder is no exception; its central plot points are hidden relationships and a strange disappearance. It begins well enough, with a dandy premise: Tolefree and Farrar, on a holiday in the Scottish Highlands, decide to rent a boat and sail her out of one of the fjordlike lochs into the Atlantic.

A sudden storm shipwrecks them on the tiny island of Eilean Rona, where they are rescued by the lord of the isle, Martin Gregg; artist Bill Parracombe; and two odd and fiercely loyal Scotsmen, Fergus and Jamie. Also staying at the island’s ancient castle for the summer are Gregg’s wife and small son, and the boy’s governess.

The storm continues to batter Rona, preventing any of them from leaving. A chance remark by Farrar, about a retired sea captain he knows named Strachan who lives over on the mainland, for some reason seems to frighten everyone; so does the remark that Tolefree is a detective.

It soon becomes clear that Strachan had been hunting lost treasure on the island and disappeared one foggy Sunday three months before, along with his boat and a mysterious companion; and that the inhabitants of Rona know something about that disappearance and are desperate to protect their guilty knowledge.

So far, so good. But Walling spoils the stew by interminable passages of cat-and-mouse dialogue, annoying cryptic remarks from Tolefree, and a lot of rather silly running around. He also lets the reader know early on that Tolefree and Farrar do not fear for their lives; they think their hosts are all swell people, even though one of them may be a murderer.

The result is plenty of mystery but no menace and therefore no tension. And the mystery isn’t satisfying, either, when its rather predictable solution is revealed.

Walling has been called (by his publishers) “the foremost exponent of the seemingly ‘quiet’ mystery, the civilized story with … excitement and drama seething below the surface.”

Readers who don’t find that a euphemism for dull, and would like to examine Walling’s work for themselves, should try The Corpse in the Coppice (1935), The Corpse with the Floating Foot (1936), The Corpse with the Eerie Eye (1942), and A Corpse by Any Other Name (1943). The last-named title has some effective descriptions of Londoners coping with the wartime blackout and blitz.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 20 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

R. A. J. WALLING – The Corpse with the Dirty Face. Morrow, hardcover, 1936. UK edition; Hodder & Stoughton, hc, 1936.

Upon first inspection the black markings smeared across the victim’s face appear to be huge inkstains sustained during the act of murder. Later it’s learned that they were permanently disfiguring powder burns the dead man received during the war — World War I, that would have been.

They’re still important enough as a factor in solving the murder to give the case its title, and a good deal of diligent detective work is needed to unravel the maze of conflicting alibis that bars the way. Also needed is an explanation for the several uncharacteristic changes of plan the victim made for the evening during the crucial time just before his death.

On the scene from very nearly the beginning is Mr. Tolefree, a private detective of the “softboiled” English butler variety. The only character to display real signs of life is the dead man’s daughter, determined not to let her loved one be accused of the crime.

It takes a strenuous grip on a great number of assorted facts to solve the puzzle before Mr. Tolefree does, and even so I question the fairness of one of the essential clues. Making up for it is a solidly constructed piece of misdirection at one point, and equally pleasing was a bit of unexpected subtlety in the prologue. Even with the portentous warning Walling gives the reader in the very first paragraph, it goes unnoticed very easily. On the whole, nicely done.

A good movie it wouldn’t make, however. Too many shots of heads, doing nothing but talking.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 6, Nov-Dec 1979.

[UPDATE] 03-20-11. This, of course, is the review I promised as a follow-up to Geoff Bradley’s review of an earlier Walling mystery, which produced a lot of comments, mostly neutral (ho-hum) to negative. This one I liked, though, in spite of all the flaws I found and pointed out. Whether I’d feel the same way, today, I cannot tell you, nor have I read another by Walling since.

Coming up next: Bill Pronzini’s 1001 Midnights review of the same author’s Marooned with Murder. Be warned. He did not like it, and he is willing to tell you why.

Thu 17 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[18] Comments

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

R. A. J. WALLING – The Dinner-Party at Bardolph’s. Jarrolds, UK, hardcover, 1927. Hardcover reprint; Hodder & Stoughton, 1937. US title: That Dinner at Bardolph’s. Morrow, hc, 1928. Series character: Inspector Pierce.

A few years ago (certainly more than five, probably less than ten) I was walking past my local library and saw outside a trolley of books for sale. They consisted of tatty, much read recent books but amongst them was this title in a 1937 Hodder & Stoughton edition. It clearly wasn’t from the library itself — it’s far too old and had no library stamps — so I guess it must have been some sort of donation though I haven’t really heard of that happening over here (though I think it is common in the US).

Anyway for the sake of 30p I couldn’t really leave it there so, against my better judgement, I forked over the cash and brought it home to join the thousand or so other books awaiting my attention.

It might have stayed in the loft forever, or until my executor starts disposing of the contents, but Barry Pike had an article on another Walling book in the current issue of CADS (that well known literary magazine) and I was inspired to fish it out and give it a try.

And I’m glad I did. In many ways it was dated and slow-moving, the whodunit element was not particularly cunning, and the actions of the narrator a gentleman of the old school – were hard to credit, yet it was fascinating and held my attention well.

The story involved the death by shooting — at first assumed to be suicide — of the titular character and the subsequent disappearance of all the dinner guests. The narrator and his hardworking factotum-cum-chauffeur are involved in the clandestine movements of two of them but when murder is uncovered they become caught up in a chase to clear the names of the innocent and find out what is behind the crime.

And, as I said, it all worked — for me anyway. I probably won’t go actively searching out more Walling’s to read — I have so many other books piled up and clamouring for my attention, but if I come across one in a second hand book shop I will probably pick it up.

Editorial Comment: Geoff mentions in passing the existence of a mystery fanzine called CADS, but he failed to point out two things. First of all, that he is the editor and publisher, and then secondly, that the magazine is still going strong.

If you’re interested in articles about authors and reviews of mystery fiction that are both solidly and substantially done, you should most definitely be reading CADS. The most recent issue was #59, and copies should still be available at a cost of $14 by air or $12 by surface mail. #60 will be ready in a few weeks, says Geoff, but since postage fees will be going up in early April, the price hasn’t been determined yet.

Geoff’s mailing address can be found here, but the ad’s way out of date. Email Geoff to double check on the availability of #59 or to reserve a copy of #60. (Tell him I sent you.)

Wed 23 Aug 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

The Amazing Colossal Belgian:

A Quartet of Christie Expansions

Part 2: “Murder in the Mews”

by Matthew R. Bradley

“The Market Basing Mystery” (The Sketch, October 17, 1923; The Blue Book Magazine, May 1925) was collected in the U.S. in The Under Dog and Other Stories (1951), and in the U.K. first in Thirteen for Luck! (1966), a catch-all volume for young readers, and then in Poirot’s Early Cases (1974). It was expanded into the title novella (aka “Mystery of the Dressing Case”) of Murder in the Mews and Other Stories (truncated as Dead Man’s Mirror; 1937), which debuted in Redbook Magazine (September & October 1936). With his formidable “little gray cells,” Agatha Christie’s Belgian super-sleuth, Hercule Poirot, perhaps found the mystery itself less baffling than that barrage of appearances and titles!

First mentioned here, and thought to be based upon Basingstoke and/or Christie’s future home of Wallingford, Market Basing would be the setting for stories and novels featuring Jane Marple, Superintendent Battle, and Tommy and Tuppence Beresford; Poirot himself returned there in Dumb Witness (aka Poirot Loses a Client; 1937). Inspector Japp, while off duty “an ardent botanist,” suggests a weekend with Poirot and Hastings in that “little country town,” where he craves anonymity: “Nobody knows us, and we know nobody.” But Constable Pollard, transferred from a nearby village where he’d met Japp through “a case of arsenical poisoning,” interrupts them over an English breakfast at the local inn.

He summons them to “rambling, dilapidated” Leigh House, rented eight years ago by the virtual recluse Walter Protheroe, shot through the head; the locked door, bolted windows, and pistol in his hand suggest suicide, but per Dr. Giles, the bullet entered behind his left ear — yet the gun was in his right hand, the fingers not closed over it. There is no obvious motive, with the only apparent suspects his devoted housekeeper of 14 years, Miss Clegg, and his recently arrived guests from London, Mr. and Mrs. Parker. Examining the scene, Poirot focuses on two aspects: the smell — or lack thereof, inconsistent with Protheroe’s being a heavy smoker — and the handkerchief he had carried in his right-hand coat sleeve.

The former suggests that the window had been open all night, and the latter indicates that he was left-handed; a broken cuff-link found by the body is identified as Parker’s by Miss Clegg, who says they were neither expected nor welcome. A tramp who often slept in an unlocked shed reports overhearing Parker attempting to blackmail Protheroe, revealed as an alias for Wendover, a Naval lieutenant who “had been concerned in the blowing up of the first-class cruiser Merrythought, in 1910.” Put on trial, Parker is cleared by Poirot, who gets Miss Clegg to admit that having found Protheroe a suicide, she blamed Parker, implicating him by repositioning the gun, bolting the window, and planting the cuff-link.

Almost six times as long as the original, “Murder in the Mews” was adapted in 1989 with David Suchet on Britain’s ITV in Agatha Christie’s Poirot, which unsurprisingly omitted “Market Basing.” The third-person novella features Japp (now a Chief Inspector) but not Hastings, while Pollard and Giles have been supplanted by Divisional Inspector Jameson and Dr. Brett, respectively. This marks Jameson’s only literary appearance; played, as he was in “Mews,” by John Cording, he was interpolated into their 1990 adaptation of “The Lost Mine” (The Sketch, November 21, 1923; The Blue Book Magazine, April 1925) from the collections Poirot Investigates (1925) — here in the States — and Poirot’s Early Cases.

Taking a shortcut through Bardsley Gardens Mews to Poirot’s flat on Guy Fawkes Night, he and Japp remark that it would be perfect for a murder, since the fireworks marking the plot to blow up Parliament would hide the sound of a shot. The next morning, Japp asks Poirot to accompany him back there when summoned by Jameson to the scene of what at first seemed a suicide; he and Brett, who forced open the door, show them the body.

The set-up, with the misaligned wound and gun, is the same, but Christie rings her changes on the victim — young widow Barbara Allen, who lives with her friend Jane Plenderleith and is engaged to Charles Laverton-West, “M.P. for someplace in Hampshire” — and suspects.

Charles, with no apparent motive yet a flimsy alibi, resents being questioned, due less to guilt than to being, says Japp, a “[b]it of a stuffed fish. And a boiled owl!”; housekeeper Mrs. Pierce merely provides a torrent of chatter. Blackmailer Major Eustace met Barbara years ago in India and knew that “having borne an illegitimate child who died at three” she invented a fictitious late husband, a revelation she feared would damage Charles’s career.

Carried over are the clues of the smokeless room (Poirot invokes Conan Doyle’s “curious incident of the dog in the nighttime,” which did nothing) and cuff link, with a wristwatch replacing the handkerchief, supported by a writing table that has the pen tray on the left.

Eustace admits visiting Barbara, ostensibly to offer investment advice, but the neighbors report his saying goodbye to her at 10:20; his subsequent movements are accounted for, yet when it is realized that nobody actually saw or heard her half of the conversation from inside the doorway, he is arrested. Confronted with the truth, Jane reluctantly agrees that she cannot let Eustace — already facing a long prison sentence for an unrelated swindle — take the blame for Barbara’s death. Jane admits finding her body and suicide note, which she burned, and restaging the scene to frame Eustace, so despite its title, the case remains, as Japp puts it, “Not murder disguised as suicide, but suicide made to look like murder!”

Among her clever recombining and expanding of elements, Christie adds one that nicely shows the ingenuity of Jane, who professes first perplexity at the possibility and method of Barbara’s suicide, and then outrage at the notion of murder. Visibly discomfited when asked to unlock a cupboard full of umbrellas, golf clubs, and tennis racquets, she displays anxiety over an attache case containing old magazines and other trivia. She is later seen throwing it into the lake by the golf course, whence it is retrieved, now empty, but this is a superb piece of misdirection: she had diverted their attention to the case when her real concern was Barbara’s left-handed clubs, tossed into the undergrowth along the course.

— Copyright © 2023 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Up next: “Dead Man’s Mirror.”

Edition cited —

“The Market Basing Mystery” and “Murder in the Mews” in Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories: William Morrow (2013)

Tue 12 Feb 2019

Posted by Steve under

Magazines[18] Comments

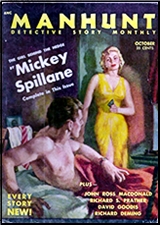

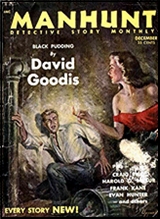

THE TORTURED HISTORY OF MANHUNT

by Jeff Vorzimmer

The first issue of Manhunt appeared on newsstands in late 1952 and within two years became the widely acknowledged successor to Black Mask, which had ceased publication the year before. The stories in Manhunt captured the noir of Cold War angst like no other fiction magazine of its time and paved the way for television anthology shows such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

Manhunt can best be described as a joint venture between publisher Archer St. John and literary agent Scott Meredith, both based in New York. In 1952, St. John published comic books and had recently ventured into and, in fact, developed 3D comics and graphic novels. His company, St. John Publishing, produced what is considered the first graphic novel, It Rhymes with Lust, in 1950, which was part crime, part romance, and followed that up later the same year with The Case of the Winking Buddha. Neither book sold very well and the line, dubbed “Pictures Novels,†was discontinued after the second title.

Archer St. John, always an admirer of Black Mask magazine, the premier pulp magazine from the 1920s through the 40s, felt that since that magazine’s demise there was a void in the world of crime-fiction magazines and an opportunity. Of course, comic book publishers don’t usually have big editorial staffs nor do they solicit manuscript submissions. For that, St. John approached Scott Meredith, a literary agent who was beginning to turn the publishing world on its ear with practices such as charging would-be writers reading fees and submitting manuscripts to publishers simultaneously, creating an auction system of competing bids.

For Scott Meredith it was an opportunity to get his stable of writers in print and create another stream of income. St. John served as the front man to avoid any ethical questions or conflict of interest charges that Meredith might otherwise face. St. John would manage the production of the magazine from layout and illustration to the printing and distribution of the magazine while Meredith’s office would supply a steady supply of fiction and editing.

Of course, it was not a very well-kept secret within the publishing business. Those in the business, with even a passing familiarity with the roster of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, would notice a preponderance of his clients on the pages of Manhunt. In fact, all ten of the most prolific contributors to the magazine were Meredith authors who, between them, contributed over one-fifth of all stories that appeared in Manhunt over the course of its fourteen-year run.

Manhunt has often been referred to, then and now, as a closed shop, only available to the Meredith stable of authors, but that’s not entirely true. As often as not, writers not represented by an agent would submit stories directly to Manhunt. These were forwarded to the Meredith office and occasionally published in the magazine, though the authors were not usually signed to a publishing contract on the strength of a single story.

This would sometimes create awkward moments when a producer from a television studio such as Revue, producers of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and M Squad, would call up the agency looking to secure the rights to a story they read in Manhunt. The Meredith agent would stall the producer, scramble to locate and sign the author, then make the deal.

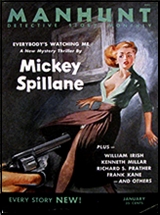

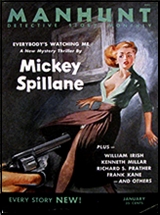

Archer St. John originally wanted to call the magazine Mickey Spillane’s Mystery Magazine to compete with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, albeit with grittier, more hard-boiled stories. Having Spillane’s name on the masthead would have been appealing to both St. John and Meredith in that, by 1952, Spillane’s first six books had combined sales of 20 million copies. His first book, I, The Jury had sold 3.5 million copies by 1953, when it was adapted for the screen.

When Scott Meredith checked Spillane’s contract with his publisher, Dutton, he found a clause that gave the publisher total control of Mickey Spillane’s name in conjunction with any books or periodicals. If they were to use Spillane’s name on the magazine they had to get Dutton’s permission. However, Dutton balked at the idea.

Dutton felt that short stories were a distraction for Spillane, and they wanted him to get back to the business of writing novels. At that point, it had been over a year since Spillane had delivered his last novel to them (and it would be ten years before he delivered his next one). The name of the magazine was changed to Manhunt, a named borrowed from a then-defunct crime comic book.

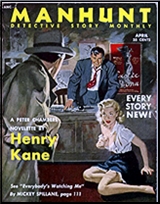

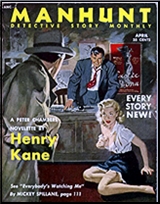

St. John intended to kick off the magazine with a Mickey Spillane story. He had heard that Collier’s Magazine had turned down a novella Spillane had written, “Everybody’s Watching Me,†and offered to serialize the novella in the first four issues of the new magazine and pay Spillane $25,000 (equivalent to $237,000 today). If Spillane’s name could not be on the masthead, it would at least be on the cover of the first four issues.

The print run of the first issue, dated January 1953, was 600,000 copies and sold out in five days. It was digest size (5½”x7½”), 144 pages and priced at 35¢ and $4 for a year’s subscription. In addition to the lead story by Spillane, the issue also included stories by Cornell Woolrich under the name of William Irish; Ross Macdonald, under his real name, Kenneth Millar; and Evan Hunter, later known by the pen name Ed McBain.

It also included a story featuring Richard Prather’s detective Shell Scott, featured in six novels of his own over the previous three years, and, who rivaled Spillane’s Mike Hammer in popularity, and another featuring Frank Kane’s Johnny Liddell. Stories by Floyd Mahannah, Charles Beckman, Jr. and Sam Cobb (Stanley L. Colbert) rounded out the issue.

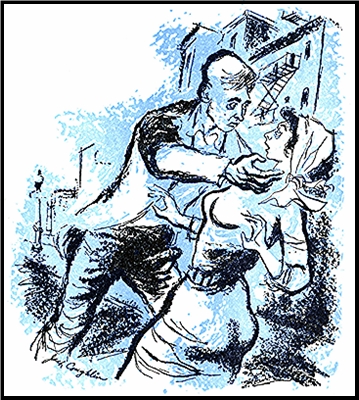

St. John had his favorite artist, Matt Baker, a black man in the predominantly white world of comic book illustration, do the artwork for Manhunt. Baker was the artist who had done the panels for the first of the two graphic novels St. John had published, but brought an entirely new look to the Manhunt illustrations, heavy ink and each highlighted with a different spot color. Each story had one illustration on the first page in a style not unlike Manhunt.

Pages from the February 1953 issue of Manhunt with illustrations by Matt Baker

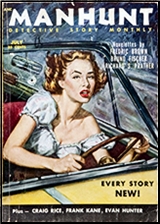

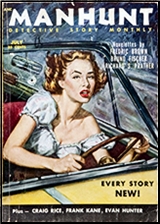

Baker himself would do most of the illustrations for the first nine issues, thereby setting the style used for the entire 15-year run. Up-and-coming young artists such as Robert McGinnis, Walter Popp and Robert Maguire, as well as older, more established artists, such as Frank Uppwall and Willard Downes, painted the covers.

The editorial note on the contents page of the second issue stated that the press run of the first issue probably should have been closer to a million copies. St. John apparently split the difference and ran 800,000 copies of the second issue. In addition to the second installment of “Everybody’s Watching Me,†the lead story was another by Kenneth Millar, a Lew Archer story titled “The Imaginary Blonde†under his new pseudonym John Ross Macdonald.

There were also two more stories by Evan Hunter under the pseudonyms Richard Marsten and Hunt Collins, a Paul Pine story by John Evans, as well as stories by Jonathan Craig (Frank E. Smith), Fletcher Flora, Richard Deming, Eleazar Lipsky and Michael Fessier.

In addition to the contributors of the first two issues, the third issue was notable in that it included stories by older, more established writers such as Leslie Charteris with a Saint story, Craig Rice (Georgiana Craig) with a John J. Malone story, as well as stories by William Lindsay Gresham and Bruno Fischer.

The third issue also contained another two stories by Evan Hunter, one under the pseudonym Richard Marsten. In fact, Evan Hunter contributed 16 stories to the first 9 issues of Manhunt under his own name and various pseudonyms and 48 stories over the entire life of the magazine, making him the most prolific contributor by far. For a magazine that was supposed to be all about Mickey Spillane, it was turning out to be about Evan Hunter.

By mid-1953, St. John, with Meredith’s help, started a campaign to lure big name authors to Manhunt. They approached James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, Rex Stout, Erle Stanley Gardner, Nelson Algren and Erskine Caldwell. They offered as much as $5,000 (about $47,000 today) for a 5,000-word story. This was the kind of money writers could expect from the slick magazines, but not from the pulps.

Many writers like Erle Stanley Gardner initially balked at the idea of publishing in Manhunt, but eventually succumbed. Gardner’s first response to his agent was, “I hate to turn down an offer of $5000 for a story, but, confidentially, I don’t like this magazine concept with which Manhunt started out. I think it is a definite menace to legitimate mystery fiction.â€

By the end of the decade all the big-name writers, including Gardner, had agreed to publish stories in Manhunt, though many appeared only once, the last being the only appearance by Raymond Chandler. His story, “Wrong Pigeon,†previously published only in England, appeared in the February 1960 issue.

The year 1953 would be the peak year for St. John Publications. Manhunt was turning out to be one of its biggest-selling titles, spawning spin-off titles Verdict and Menace, and its 3D comics were selling millions of copies. The company had 35 different comic book titles with several lines of romance comics, Mighty Mouse and Three Stooges comic book lines, for a total of 169 issues published that year.

Another of Archer St. John’s projects was a man’s magazine that would include articles of interest to men, photos of women in various stages of undress and quality fiction. However, he was concerned about the post office not allowing the mailing of what they would certainly deem pornographic material to subscribers. After Playboy appeared in December 1953, he was emboldened to move ahead with the project.

In 1954, Archer brought in his 24-year-old son Michael to help run the business, while he focused on the new men’s magazine, Nugget. Again, he turned to his favorite artist, Matt Baker, to do the illustrations in the magazine. Although that year would turn out to be another good year for St. John Publications, there was trouble on the horizon.

In the spring of 1954, there was a backlash against violence in comic books that were clearly aimed at children. The crusade was led by New York psychiatrist Fredric Wertham who published the now-infamous Seduction of the Innocent, a book-length study of the adverse effects of violent comic books on young minds, and led to a Senate investigation, which issued its own Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency Interim Report that included a list of comic book titles it deemed inappropriate for children. There were, of course, some St. John titles on the list.

It was also apparent in early 1954 that 3D comics were just a passing fad. Sales of 3D comics plummeted to the point that, by March of 1954, 3D titles had all but disappeared. The sales of comic books in general were in a slump, brought on in large part by the scare created by politicians and PTA groups after the Wertham study.

Other forces were coming to bear that would have a personal effect on Archer St. John and the fate of St. John Publications. In August of 1954, President Eisenhower signed The Communist Control Act, which outlawed the Communist Party in the United States. Anyone who had ever been a member of the Communist Party could face imprisonment or even the revocation of citizenship.

Archer’s brother, the famous journalist Robert St. John, living a self-imposed exile in Switzerland and doing research for books on South Africa and Israel, was determined by the FBI to have been a member of the Communist Party. On September 24, 1954, Robert St. John was summoned to the American Consulate in Geneva and stripped of his passport. When Robert asked why his passport was being taken from him, the reply from the Consul-General was that it was because of his Communist Party activity.

Robert turned to his brother Archer back in the States for help to get his passport reinstated and the necessary affidavits for the appeal. Over the following months Archer, who was very close to his brother Robert, became increasingly frustrated by the stonewalling he got from the U.S. government on his brother’s case.

Adding to his personal turmoil was the fact Archer was separated from his wife and living at the New York Athletic Club. His employees at St. John Publications also suspected he was addicted to amphetamines in addition to being an alcoholic. By mid-1955 Robert’s case had still not been decided, though he had submitted numerous affidavits from noted citizens that affirmed that he was never a member of the Communist Party.

In August, Archer told family members that he was being blackmailed, but didn’t give anyone any details. His son Michael told him not to give in to the blackmailers. Archer told his son that he was staying at the apartment of a friend but wouldn’t tell Michael where.

On Friday night August 12, 1955, Robert St. John got a call in Switzerland from Archer in New York who told him, “Never in my life have I felt so frustrated. I feel like I’m banging my head against a stone wall. I see no possibility of my getting your passport back. I’ve done everything in my power to help you, but I’ve failed. I’m sick over this.†The next morning Robert got a call telling him that his brother had overdosed on sleeping pills, an apparent suicide. He was 54 years old.

At times, Archer St. John’s life resembled a story from the pages of Manhunt — Al Capone’s gang once kidnapped him when he was young newspaper publisher — and his death was no different. The apartment where Archer had been staying was a duplex penthouse owned by an attractive, redheaded former model and divorcee named Frances Stratford. She had been sleeping in an upstairs bedroom and had found Archer downstairs lying next to the couch, unresponsive, at 11:30 a.m. that Saturday morning.

A couple had been seen leaving the apartment the night before, and the police were investigating. On Monday, the New York Daily News reported, “A couple of shadowy West Side characters, a man and a woman, suspected of feeding dope pills to magazine publisher Archer St. John, were being hunted … by detectives investigating St. John’s mysterious death in the penthouse apartment of a former Powers model.â€

After St. John’s death, his wife, Gertrude-Faye, known as “G-F†or “Geff,†showed up at the offices of St. John Publications and promptly fired the entire staff, including Matt Baker. Apparently, she hadn’t wanted anyone around who knew about her husband’s affairs. The irony was that none of the staff knew anything about St. John’s private love life, not even Baker who was probably as close to him as anybody.

Despite the failure of the previous Manhunt clones, Verdict, which lasted only four issues in late 1953 and Menace, which lasted two issues, the following year, Michael St. John decided to expand his own editorial staff and to introduce yet two more titles, Mantrap and Murder! in 1956. Unfortunately, the new titles suffered from the same lackluster sales of the first two spin-off titles and were discontinued just as quickly.

Undaunted by the failure of four new titles in as many years, Michael kept searching for a formula that would repeat the success of Manhunt. What Michael and his business manager, Richard Decker, came up with was an opposite, more genteel, direction. They approached Alfred Hitchcock with an offer to license his name and image for a mystery digest.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine was an immediate success and, in fact, sales would steadily increase throughout the rest of the decade while those of Manhunt were in steady decline, down to 169,000 by 1957. Its digest size, with two-column layout and heavily inked spot color illustrations, were identical to Manhunt’s.

In an effort to boost sales of both Manhunt and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, St. John and Decker decided to increase the size of both magazines from their current digest size to regular magazine size to get, what they hoped would be, more attention on newsstands. What it got Manhunt was the unwanted attention of the Federal District Attorney.

After only the second issue at the bigger magazine size, Michael St. John, Richard E. Decker, Charles W. Adams (the Art Director) and Flying Eagle Publications (a subsidiary of St. John’s Publications and holding company of Manhunt) were indicted on March 14, 1957, for “mailing or delivery copies of the April, 1957, issue of a publication entitled Manhunt containing obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy or indecent matter†in violation of United States Penal Code 18 U.S.C. §1461.

In District Court in Concord, New Hampshire, St. John’s lawyers moved to have the charges dismissed on the grounds that the complaint didn’t identify what article was specifically being charged in the issue as “obscene, lewd, filthy or indecent.†They argued that “the indictment is so loosely drawn that it would not afford them protection from further prosecution.†District Court Judge Aloysius J. Connor agreed and threw out the indictments on August 7, 1957.

Federal prosecutors promptly refiled charges with specific complaints: “All six of the stories have definitely weird overtones and can certainly be characterized as crude, course, vulgar, and on the whole disgusting. But tested by the reaction of the community as a whole — the average member of society — it seems to us that only the feature novelette, ‘Body on a White Carpet,’ and the illustration appearing on page 25 accompanying the story entitled ‘Object of Desire,’ could be found to fall within the ban of the statute as limited in its application by the important public interest in a free press protected in the First Amendment.†The defendants faced a fine of $5,000 ($43,000 in today’s dollars) and up to five years in prison.

The offending illustration by Jack Coughlin accompanying the story

“Object of Desire†on page 25 of the April 1957 issue.

On December 1, 1958, the final verdict of the District Court jury was that Flying Eagle Publications and Michael St. John were guilty and fined $3,000 ($26,000 today). Judge Connor gave St. John a separate fine of $1000, a suspended sentence of six months in jail and two-year probation. Richard E. Decker and Charles W. Adams were acquitted. Michael St. John immediately appealed the verdict and the case went to Federal Appeals Court.

On January 21, 1960, the Federal Appeals Court in Boston set aside the verdict of the District Court and ordered a new trial. Chief Judge Peter Woodbury found that the prosecutors had erred in their instructions to the jury by telling them that two defendants, Decker and Adams, originally listed on the indictment had “been separated from this action†rather than that they were acquitted.

A year later the Court of Appeals upheld the decision of the Circuit Court on January 10, 1961, and Judge Bailey Aldrich upheld the original fine of $5,000. After three years and nine months of litigation, St. John Publishing was financially drained. The circulation of Manhunt had dropped to 100,000, and Richard Decker had split with St. John in the summer of 1960, taking Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine with him to Palm Beach, Florida.

Scott Meredith had always been annoyed with what seemed to be chronic cash-flow problems at St. John, and it only got worse. The magazine limped along for the next six years, and fewer of Meredith’s writers appeared in the magazine. Only 33 stories by the top ten Meredith contributors appeared in the 1960s.

Only three Evan Hunter stories appeared in Manhunt in the 60s, the last story, fittingly, in the last issue of April/May 1967. By then the circulation had dropped to a little over 74,000 copies. Michael St. John decided to get out of the publishing business entirely and sold off all the assets of St John Publishing, including Nugget.

— From the forthcoming book The Best of Manhunt, Stark House Press, July 2019

Sources:

Aldrich, Baily, Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals, Flying Eagle Publications v. United States, 285 F.2d 307, January 10, 1961

Ashley, Michael, author, Kemp, Earl and Ortiz, Luiz editors, Cult Magazines A-Z: A Curious Compendium of Culturally Obsessive & Curiously Expressive Publications, 2009, Nonstop Press

Benson, John, Confessions, Romances, Secrets, and Temptations: Archer St. John and the St. John Romance Comics, 2007, Fantagraphics Books

Benson, John, Romance Without Tears, 2003, Fantagraphics Books

Fugate, Francis L. and Roberta B., Secrets of the World’s Best-Selling Writer, 1980, William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Carlson, Michael, “Interview with Mickey Spillane,” Crime Time website, June 29, 2002

Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, July 8, 1925, pg. 16

Collins, Max Allan and Traylor, James L, Spillane (to be published in 2020)

Cook, Michael L., Monthly Murders: A Checklist and Chronological Listing of Fiction in the Digest-Size Mystery Magazines in the United States and England, 1982

Horowitz, Terry Fred, Merchant of Words: The Life of Robert St. John, 2014, Rowman & Littlefield

Meredith, Scott and Meredith, Sidney, The Best From Manhunt, 1958, Perma-Books

Morgan, Hal and Symmes, Dan, Amazing 3-D, 1982, Little, Brown and Company

Morrison, Henry, Literary Agent and former Scott Meredith Literary Agency employee (1957-1964), Interview, January 29, 2019

Nashua Telegraph, Nashua, NH, January 22, 1960, pg. 2

Nashua Telegraph, Nashua, NH, January 11, 1961, pg. 2

New York Daily News, New York, NY, August 15, 1955, pg. C5

N. W. Ayers & Sons Directory of Newspapers and Periodicals, 1954-1967

The Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa, Canada, March 2, 1957, pg. 2

The Portsmouth Herald, Portsmouth, NH, March 15, 1957, pg. 7

The Portsmouth Herald, Portsmouth, NH, December 2, 1958, pg. 8

Quattro, Ken, Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could, 2006, www.comicartville.com

Waller, Drake, It Rhymes with Lust, 1950, 2007, Dark Horse Books

Woodbury, Peter, Chief Judge, United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit, Flying Eagle Publications v. United States, 273 F.2d 799, January 21, 1960

Sat 12 Jan 2013

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

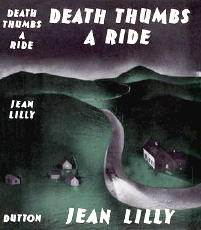

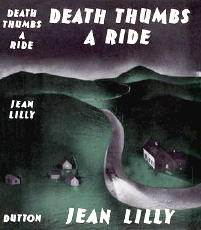

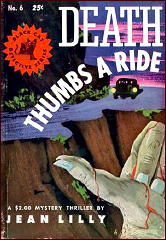

JEAN LILLY – Death Thumbs a Ride. Dutton, hardcover, 1940. Black Cat Detective Series #6, digest-sized paperback, 1943.

“Two murders would probably have gone unsuspected during the last year if Eunice Hale had not eaten a chicken croquette of questionable virtue.” The two murders were the death of a woman, of apparently natural causes, at a tourist camp in the Adirondacks and the presumed hit-and-run death of a senator’s gardener in the same area.

Even with the aid of the chicken croquette they would have remained unsuspected except for the interest of vacationing district attorney Bruce Perkins, who is asked to investigate a jewel theft but prefers to find the alleged hit-and-run driver and begins to doubt the naturalness of the woman’s death.

While the opening sentence is a good one, the rest of the prose does not get any better than slightly above pedestrian and the characters are essentially lifeless. Lilly somewhat makes up for this with her primary setting, unusual in mysteries, I believe: a lower-middle-class tourist camp. (Could there be such a thing as an upper-class tourist camp?)

Lilly also provides a, for the most part, fair-play mystery. For the most part, I say, since I could find no explanation, and I certainly couldn’t figure out how the gardener died, or even if it was murder. Maybe the Black Cat publication was abridged and the publisher neglected to mention it.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 4, Fall 1992.

Bibliographic Notes: Death Thumbs a Ride was the last of three recorded cases for DA Bruce Perkins, and the last of four crime novels written by Jean Lilly:

LILLY, JEAN (McCoy), 1886-1961. Born in Milford, Michigan; died in Wallingford, Pennsylvania.

The Seven Sisters (n.) Dutton 1928 [Connecticut]

False Face (n.) Dutton 1929 [Bruce Perkins; Academia]

Death in B-Minor (n.) Dutton 1934 [Bruce Perkins; Long Island, NY]

Death Thumbs a Ride (n.) Dutton 1940 [Bruce Perkins; New York]

Thanks to Allen J. Hubin and Crime Fiction IV for the above information. Also note that the contemporaneous Kirkus review suggests that there are no loose ends, at least in the hardcover edition.

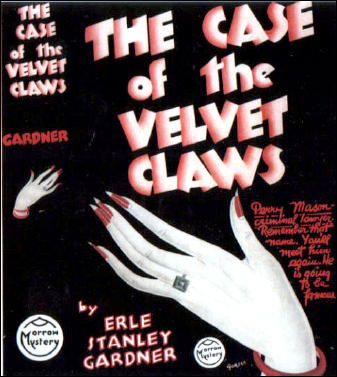

Thu 28 Jul 2011

THE FRONT COVER:

THE INSIDE FRONT JACKET FLAP:

A MORROW MYSTERY

To Readers of Detective Stories:

One day last December our editorial and sales departments agreed that too many mystery stories are being published in America and decided to accept no more such novels for at least six months. The next day two manuscripts were received. They were both by the same author. They were both detective stories. They were both accepted at once for publication.

The Case of the Velvet Claws is one of those manuscripts. The second will be published in the fall. (*) And both sales and editorial departments claim the credit for being the first to prophecy that Erle Stanley Gardner will find a place immediately as one of the most popular authors of detective fiction.

We hope that after reading this book you will agree we were justified in changing our minds.

* The Case of the Sulky Girl.

Perry Mason, criminal lawyer, is retained by a much-too-beautiful woman who obviously is concealing more than she is telling. She has heard that Perry Mason not only a law unto himself, but that he never lets a client down. She has been indiscreet, and is involved in blackmail.

The case is immediately complicated by murder, and Perry Mason finds himself as busy keeping clear of the law himself as he is in saving his client. The action is swift, dramatic, convincing. The handling and solution of the case are well developed and logical — perhaps because the author is a practicing lawyer with a trained legal mind.

Mr. Gardner’s writing has a style and personality of its own. His characters are colorful and vital. The lawyer, Perry Mason, and his charming secretary, Della Street, we believe, will become famous characters to all detective story enthusiasts.

WILLIAM MORROW & COMPANY

386 Fourth Avenue New York

THE INSIDE BACK JACKET FLAP: A detailed synopsis of –In Time for Murder, by R. A. J. Walling, a mystery novel also published by Morrow.

THE BACK COVER: A statement of the philosophy of the publisher relative to detective fiction, and a list of the titles they had recently published:

R. A. WALLING

Stroke of One

–In Time for Murder

CHARLES G. BOOTH

Those Seven Alibis

Gold Bullets

CHRISTOPHER BUSH

The Case of the April Fools

Cut Throat

WALTER F. EBERHARDT

A Dagger in the Dark

ROGER DENBIE (upcoming)

Death on the Limited (April 1933)

COVER PRICE: $2.00.

NOTE: Thanks to Bill Pronzini and Mark Terry for the cover images used to provide the information above.

Wed 3 Nov 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

SELDON TRUSS – Where’s Mr. Chumley? Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1948. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1949. Reprinted in Two Complete Detective Books, No. 59, November 1949.

Where indeed is the Reverend Mr. Chumley, curate at Charwell? The police suspect that he is off with an illicit lover, but those who know the good man are dubious, perhaps incredulous. As well they might be, for the unfinished letter to his “lover” turns out to be a forgery.

Under the guise of a commercial gentleman, Chief Inspector Gidleigh, C.I.D., takes charge of the investigation into Chumley’s disappearance and has also to contend with a possible abortionist, a seeming suicide, and the odious Mr. Twigg. Nobody’s fool, Gidleigh gets part of it right.

While Truss is not in the top rank of mystery writers, he (she?) is certainly high in the second tier. Humor, interesting and sympathetic characters, if one does not count the child Maisie of the marbly eyes, and a splendid plot make this novel, as well as others by Truss, worth trying to find.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

Bio-Bibliographic Data: If (Leslie) Seldon Truss (1892-1990) is not male, I hope someone will leave a comment to let us know. His (I am presuming) writing career extended from 1928 to 1969, and included some 40 crime novels, including one written as by George Selmark.

Inspector Gidleigh appeared in 22 or 23 of these (when one non-Gidleigh book was reprinted, Gidleigh showed up in it as the detective in charge), while Detective Inspector Shane appeared in six and Inspector Bass in yet another three.

[UPDATE] 11-07-10. From Victor Berch comes the following note about Seldon Truss:

“Here is what I’ve managed to gather from a variety of records: Leslie Seldon Truss was the son of George Marquand, an agent for a produce company, and Ann Blanch (Seldon) Truss on August 21, 1892 in Wallington, Surrey, England.

“According to his enlistment record in WW I, he had previously been a film producer for Gaumont Film Co. On the record dated Oct 8, 1915, he lists his age as 23 years and 2 months. He served with the 2nd Scots Guard during WW I.

“He died Feb 5, 1990 at Hastings and Rother, East Sussex, England. He was a member of the Society of Authors and the Crime Writers Association. I think this should clear up his sex gender once and for all.”

Wed 6 Oct 2010

100 Good Detective Novels

by Mike Grost

These are all real detective stories: tales in which a mystery is solved by a detective. Real detective fiction tends to go invisible in modern society, in which many people prefer crime fiction without mystery.

The list is in chronological order but unfortunately omits many major short story writers: G. K. Chesterton, Jacques Futrelle, H. C. Bailey, Edward D. Hoch, and other greats.

Émile Gaboriau, Le Crime d’Orcival (1866)

Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone (1868)

Israel Zangwill, The Big Bow Mystery (1891)

Anna Katherine Green, The Circular Study (1900)

Edgar Wallace, The Four Just Men (1905)

Cleveland Moffett, Through the Wall (1909)

John T. McIntyre, Ashton-Kirk, Investigator (1910)

R. Austin Freeman, The Eye of Osiris (1911)

E. C. Bentley, Trent’s Last Case (1913)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Valley of Fear (1914)

Clinton H. Stagg, Silver Sandals (1914)

Johnston McCulley, Who Killed William Drew? (1917)

Octavus Roy Cohen, Six Seconds of Darkness (1918)

Mary Roberts Rinehart & Avery Hopwood, The Bat (1920)

Donald McGibeny, 32 Caliber (1920)

Carolyn Wells, Raspberry Jam (1920)

Freeman Wills Crofts, The Cask (1920)

A. A. Milne, The Red House Mystery (1922)

G. D. H. Cole, The Brooklyn Murders (1923)

Carroll John Daly, The Snarl of the Beast (1927)

Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest (1927)

Horatio Winslow and Leslie Quirk, Into Thin Air (1929)

Samuel Spewack, Murder in the Gilded Cage (1929)

Thomas Kindon, Murder in the Moor (1929)

Mignon G. Eberhart, While the Patient Slept (1930)

Victor L. Whitechurch, Murder at the College / Murder at Exbridge (1932)

Ellery Queen, The Greek Coffin Mystery (1932)

Anthony Abbot, About the Murder of the Circus Queen (1932)

S. S. Van Dine, The Dragon Murder Case (1933)

Helen Reilly, McKee of Centre Street (1933)

Dermot Morrah, The Mummy Case (1933)

Dorothy L. Sayers, The Nine Tailors (1934)

Milton M. Propper, The Divorce Court Murder (1934)

John Dickson Carr, The Three Coffins / The Hollow Man (1935)

Georgette Heyer, Merely Murder / Death in the Stocks (1935)

David Frome, Mr. Pinkerton Has the Clue (1936)

Nigel Morland, The Case of the Rusted Room (1937)

Cyril Hare, Tenant for Death (1937)

Baynard Kendrick, The Whistling Hangman (1937)

Ngaio Marsh, Death in a White Tie (1938)

R. A. J. Walling, The Corpse With the Blue Cravat / The Coroner Doubts

(1938)

Dorothy Cameron Disney, Strawstacks / The Strawstack Murders (1938-1939)

Rex Stout, Some Buried Caesar (1938-1939)

Rufus King, Murder Masks Miami (1939)

Theodora Du Bois, Death Dines Out (1939)

Erle Stanley Gardner, The D.A. Draws a Circle (1939)

Agatha Christie, One Two, Buckle My Shoe / An Overdose of Death (1940)

J. J. Connington, The Four Defences (1940)

Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely (1940)

Frank Gruber, The Laughing Fox (1940)

Anthony Boucher, The Case of the Solid Key (1941)

Stuart Palmer, The Puzzle of the Happy Hooligan (1941)

Kelley Roos, The Frightened Stiff (1942)

Cornell Woolrich, Phantom Lady (1942)

Frances K. Judd, The Mansion of Secrets (1942)

Helen McCloy, The Goblin Market (1943)

Anne Nash, Said With Flowers (1943)

Mabel Seeley, Eleven Came Back (1943)

Norbert Davis, The Mouse in the Mountain (1943)

Robert Reeves, Cellini Smith: Detective (1943)

Hake Talbot, The Rim of the Pit (1944)

John Rhode, The Shadow on the Cliff / The Four-Ply Yarn (1944)

Allan Vaughan Elston & Maurice Beam, Murder by Mandate (1945)

Walter Gibson, Crime Over Casco (1946)

George Harmon Coxe, The Hollow Needle (1948)

Wade Miller, Fatal Step (1948)

Alan Green, What a Body! (1949)

Hal Clement, Needle (1949)

Bruno Fischer, The Angels Fell (1950)

Jack Iams, What Rhymes With Murder? (1950)

Richard Starnes, The Other Body in Grant’s Tomb (1951)

Richard Ellington, Exit for a Dame (1951)

Lawrence G. Blochman, Recipe For Homicide (1952)

Day Keene, Wake Up to Murder (1952)

Isaac Asimov, The Caves of Steel (1953)

Henry Winterfeld, Caius ist ein Dummkopf / Detectives in Togas (1953)

Craig Rice, My Kingdom For a Hearse (1956)

Frances and Richard Lockridge, Voyage into Violence (1956)

Harold Q. Masur, Tall, Dark and Deadly (1956)

James Warren, The Disappearing Corpse (1957)

Seicho Matsumoto, Ten to sen (Point and Lines) (1957)

Michael Avallone, The Crazy Mixed-Up Corpse (1957)

Ed Lacy, Shakedown for Murder (1958)

Lenore Glen Offord, Walking Shadow (1959)

Allen Richards, To Market, To Market (1961)

Christopher Bush, The Case of the Good Employer (1966)

Randall Garrett, Too Many Magicians (1967)

Michael Collins, A Dark Power (1968)

Merle Constiner, The Four from Gila Bend (1968)

Bill Pronzini, Undercurrent (1973)

Nicholas Meyer, The West End Horror (1976)

Thomas Chastain, Vital Statistics (1977)

William L. DeAndrea, Killed in the Ratings (1978)

Clifford B. Hicks, Alvin Fernald, TV Anchorman (1980)

Donald J. Sobol, Angie’s First Case (1981)

Kyotaro Nishimura, Misuteri ressha ga kieta (The Mystery Train

Disappears) (1982)

K. K. Beck, Murder in a Mummy Case (1986)

Jon L. Breen, Touch of the Past (1988)

Stephen Paul Cohen, Island of Steel (1988)

Earl W. Emerson, Black Hearts and Slow Dancing (1988)

Editorial Comment: This will do it for today, but I do have one more list to post. David Vineyard sent it to me this morning. It’s a followup to his previous list, consisting of what he calls “100 Important Books From Before the Golden Age.” The cutoff date for these is 1913, which is where his earlier list began. While not all of the books on this new list may be crime fiction, they’re all important to the field. Look for it soon!

Thu 19 Nov 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

MICHAEL CONNELLY – The Narrows. Little Brown & Co., hardcover, May 2004. Reprint paperback: Grand Central, March 2005.

Harry Bosch is working as a PI when he’s approached by Graciela McCaleb to look into the death of her husband Terry, a former FBI agent, and friend of Harry’s. Terry had presumably died of a heart attack while working on his boat on an extended charter, but Graciela has discovered that Terry’s medication had been replaced, causing his death.

Meanwhile FBI agent Rachel Walling, exiled to the Dakotas after the botch-up of the serial killer case involving “The Poet” is assigned to a task force near Las Vegas because it looks like the latter has returned with the discovery of the bodies of several men pin-pointed by a GPS device sent to the Bureau.

Looking into Terry’s death, Harry discovers that Terry was investigating several unsolved crimes and offering his expertise to the local police. Among those cases was one involving those missing men.

Harry also finds of photos of Graciela and her children, along with a photo of a road sign bearing the word “Zzyzx,” which is where the bodies of those missing men are discovered. So pretty soon Harry is nosing around in an FBI investigation, and Rachel Walling decides to tag along with Harry once she realizes she’s only being used as a stalking horse by her colleagues.

A pretty good effort. I gather this was the one Connelly wrote to show his displeasure with the way Clint Eastwood adapted his novel Bloodwork by killing off his Terry McCaleb character. It is quite suspenseful and decently plotted.

Harry even gets beat up somewhat, one of the prerequisites of the PI novel, even though by story’s end he has decided to go back to the LAPD.