Search Results for 'Stuart Palmer'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 2 Apr 2023

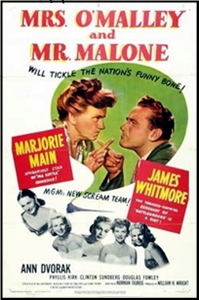

STUART PALMER & CRAIG RICE “Once Upon a Train.†Hildegarde Withers & John J. Malone. First appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, October 1950. Original title or published later as “Loco Motive.†Collected in People vs. Withers & Malone (Simon & Schuster, 1953; Award paperback, 1965). Filmed as Mrs. O’Malley and Mr. Malone (MGM, 1950, with Marjorie Main as Harriet “Hattie” O’Malley and James Whitmore as John J. Malone).

In Ellery Queen’s introduction to the collection of Withers-Malone stories, of which there were six, they say that this was the first known collaboration between two mystery writers on a tale in which their respective primary characters showed up to solve a case together. This could very easily be true.

When Malone, a somewhat disreputable Chicago lawyer finds that his most recent client, a city official accused of embezzling $30,000 from municipal funds, and a man he has just gotten off from those charges, is on a train headed for New York City — and without paying him — what is there to do rush to the station and board the very same train.

Along with several other people crying for his scalp, as it is clear that the man’s innocence is still very much in doubt. It is no wonder that his body is found at length very much dead. And in whose train compartment? None other than the horse-faced schoolteacher Miss Withers, whose accommodation adjoins Mr. Malone’s.. As they furiously move the body back and forth between their separate compartments as needed, which is often, they still manage to find time to solve the case together.

Which case is one the screwballiest detective stories you can imagine, with a laugh or a chuckle every other paragraph, if not oftener.

When they made a movie out of this, they had to change Miss Withers name to Mrs. O’Malley for copyright reasons, and no, Marjorie Main is not my idea of Miss Withers, either, but James Whitmore did passably well as Mr. Malone, if not better.

Sun 21 Jul 2019

STUART PALMER “The Riddle of the Dangling Pearl.” Novelette. Hildegarde Withers. First published in Mystery, November 1933. Collected in Hildegarde Withers: Uncollected Riddles (Crippen & Landru, 2002). Reprinted in The Big Book of Reel Murders: Stories that Inspired Great Crime Films, edited by Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime, softcover, forthcoming November 2019). Film: The Plot Thickens, RKO, 1936, with Zasu Pitts as Miss Withers and James Gleason as Oscar Piper.

Things were different back in 1933. When Inspector Oscar Piper of the NYPD gets a call from an associate curator at the Cosmopolitan Museum of Art asking for police assistance, he being shorthanded at the moment, sends schoolteacher Miss Hildegarde Withers to act in his stead.

It’s a good thing she’s on hand, though, for as soon as she arrives she sees the man she is to meet falling down a long flight of stairs and landing on the floor below, quite dead. This is only the prelude to several other extraordinary things happening at the museum that day, including the disappearance of a extremely valuable Cellini cup, ordinarily kept under close guard at all times.

While I was reading this early Miss Withers tale, I was somewhat annoyed by the clutter of characters, much more than usual, I thought, not to mention the flurry of activity surrounding them, almost non-stop. Once finished, though, and looking back, it’s easy to see how well the story was constructed, brick by brick, and everything in its place, precisely when needed.

While there’s no depth to either the characters or the story, it is a lot of fun to read.

I’ve not seen the movie based on this story in a long time, but I have to agree with Otto Penzler’s assessment in his introduction to the story that Zasu Pitts was the wrong person chosen to replace Edna May Oliver in the leading role. He adds that “The screenplay provides a different motive for the murder, different suspects, and a different murderer.” He does go on to say that the movie retains the same comic tone as the story, however.

Tue 23 Feb 2016

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini & George Kelley:

STUART PALMER & CRAIG RICE – People vs. Withers and Malone. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1963. Paperback reprints: Award A146F, 1965; International Polygonics, 1991.

Intermittently from the late Forties into the early Sixties, Palmer and his good friend and fellow mystery writer Craig Rice, with whom he had worked on the scripting of the 1942 film The Falcon’s Brother, collaborated on half a dozen novelettes for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Each story teams the crusty Miss Withers, that “tall, angular person who somehow suggested a fairly well-dressed scarecrow,†with Rice’s hard-drinking, womanizing Chicago lawyer, John J. Malone. And all six are collected in this volume.

Working in tandem, Withers and Malone solve what the dust-jacket blurb describes as “hectic, hilarious homicides.†A fair assessment: Both Palmer and Rice wrote cleverly constructed, fair-play whodunits flavored with (sometimes wacky) humor, and the blending of their talents produced some memorable stories.

One is the title novelette, in which Hildegarde and John J. hunt for a missing witness in the murder trial of a Malone client and wind up pulling off some courtroom pyrotechnics to rival any in the Perry Mason canon.

In “Cherchez la Frame,†the two sleuths travel to Hollywood to look for the missing wife of a Chicago gangster and find her strangled with Malone’s tie in his hotel bathroom.

But the best of the stories is probably the first Withers and Malone collaboration, “Once Upon a Train†(original title: “Loco Motiveâ€). This spoof of the intrigue-on-the-Orient-Express genre takes place on the Super-Century en route from Chicago to New York and features a dead man lurking sans clothing in Miss Withers’s compartment, the murder weapon conveniently planted in Malone’s adjoining compartment, and a combination of quick thinking by the little lawyer and a bizarre dream by the angular spinster that unmasks the culprit.

“Once Upon a Train†was one of two Withers and Malone stories sold to MG — “resulting finally,†Stuart Palmer writes in his preface, “in Mrs. O’Malley and Mr. Malone, a starring vehicle for James Whitmore, in which Miss Withers mysteriously changed into Ma Kettle.†Palmer and Rice were two of the scriptwriters on that 1951 film.

Each of these six stories is enjoyable light reading and should appeal not only to fans of either or both series, but to anyone who enjoys what Ellery Queen refers to in the book’s introduction as “madcap capers … full o’ fun.â€

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

[UPDATE] 08-09-09. The following comment was left by Jeffrey Marks on Yahoo’s Golden Age of Detection group, and is reprinted here with his permission. Jeff is the author of Who Was That Lady? Craig Rice: The Queen of the Screwball Mystery (Delphi Books, 2001).

“The stories, delightful as they are, were written almost exclusively by Palmer (a few were written after Rice’s death, so it’s a certainty.)

“Rice had indicated that although she had not known Palmer when she began the Malone series, Palmer epitomized the character — she thought Palmer resembled him in mannerism, appearance and dress.

“So she didn’t have a lot of qualms in turning him over to Palmer to write stories. Palmer made a few minor changes to the character. Malone, who had just been a rumpled dresser, now wore colorful ties and nicer suits. Other than that, Malone stayed close to Rice’s version of the lawyer.

“Rice was very uninvolved in the movie as well, being a ward of the state when it was being made. She was able to use the money to get out of debt and get control of her finances back as well.â€

Sun 14 Jun 2015

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

STUART PALMER – The Puzzle of the Silver Persian. Doubleday/Crime Club, hardcover, 1934. Dell #18, paperback, mapback edition, 1943. Bantam, paperback, 1986. Rue Morgue Press, trade paperback, 2010.

Miss Hildegarde Withers is spending the reward money from the last investigation she was involved in on a trip to Europe.

Unfortunately, she is seasick the first few days of the voyage and misses out on the activities that presumably drive a young lady to suicide by leaping off the ship six hundred miles from shore.

Or was the young lady pushed or pulled off the ship? The bar steward is accused of murdering her and takes cyanide in full view of the police. This clears up the case, in the minds of some.

Later on, however, the ship’s passengers who dined at the table with the no-longer-presumed suicide start getting black-bordered warnings. Then one of her tablemates dies, seemingly by accident. Another comes near death by poisoned cigarettes, obviously not a fortuitous circumstance.

Miss Withers investigates — and mucks it up, as far as I’m concerned. She also, at least in this novel, is a creature without personality. Stuart Palmer, it would seem, assumes either that his readers will know Miss Withers well and he doesn’t have to expend energy establishing her reality or that it really doesn’t matter if she’s not a distinct individual.

Also not believable is the pharmacopeia aboard the ship. It contains potassium of cyanide and, apparently, sodium of cyanide. What fearsome distempers these are intended to cure is left to the imagination.

There is, in addition, a chief inspector of Scotland Yard who tastes the contents of the jar in which the potassium of cyanide is supposed to be. A trifle foolhardy, one would think.

For puzzle lovers — and those who like novels in which cats figure prominently — only.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 4, July-August 1987.

Wed 4 Mar 2015

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Usually I try to have my column finished by the end of each month so it can be posted around the beginning of the next, but having a February column ready by late January proved impossible. Reason One: To my surprise and delight, a book of mine that came out last year, a little trifle called Judges & Justice & Lawyers & Law, was nominated for an Edgar by Mystery Writers of America, which meant that first I had to decide whether at my advanced age I wanted to come to New York late in April for the Edgars dinner, and second that I had to find a decent place to stay that wouldn’t cost me a pair of limbs that I still need.

Reason Two: I was recently asked to write something for the 75th anniversary issue of EQMM, which comes out next year, and have been spending time trying to cobble something together that would be worthy of the occasion. I’m happy to report that the piece is coming along nicely.

Reason Three: I’m also trying to put the final touches on another book — one that has nothing to do with our genre and wouldn’t be nominated for an Edgar even if pigs started to fly — and last-minute glitches have been gathering on the horizon like Hitchcock’s birds.

Reason Four: Keep reading.

Reason Five: I simply couldn’t think of anything relevant to the genre that I wanted to say, so finally I decided to give up the idea of a February column and shoot for March. Bang.

A number of years ago I devoted part of a column to a Stuart Palmer story, now more than 80 years old, which begins at a St. Patrick’s Day parade on which the APRIL sun is shining down. I couldn’t imagine how that howler got past any editor but at least took comfort from the fact that the story never appeared in EQMM and therefore that the gaffe didn’t get by the eagle eye of Fred Dannay, probably the most meticulous editor the genre has ever seen.

A week or two ago I stumbled upon another Palmer story for which I can’t say the same. “The Riddle of the Green Ice†first appeared in the Chicago Tribune (April 13, 1941) but was reprinted in Volume 1 Number 2 of EQMM (Winter 1941-42) and included in The Riddles of Hildegarde Withers (Jonathan pb #J26, 1947), a paperback collection Fred edited.

In the first scene the display window of a jewelry store on Manhattan’s 57th Street is smashed and the thief gets away. Palmer specifically tells us that the robbery took place on a “rainy Saturday afternoonâ€. A few pages later he gives us a scene that occurs on the following Monday, which he solemnly assures us is “four days after the shattering of the jewelers’ window….â€

Yikes! How in the world could an eagle-eyed editor like Fred Dannay have missed that? Palmer’s story also appears in Fred’s collection The Female of the Species (1943), and sure enough the same gaffe pops up in that printing. Double yikes!!

In another column dating back a few years I wrote that of all the authors Anthony Boucher reviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle back in the 1940s, Ray Bradbury, who had just died, was probably the last person standing. Recently I learned I was wrong. Surviving Bradbury by several years was Helen Eustis, author of the Edgar-winning novel The Horizontal Man (1946), who died on January 11 of this year at age 98.

Well, technically perhaps I wasn’t wrong. The book was published during Boucher’s tenure at the Chronicle and he mentioned it a few times, for example when MWA awarded it the best-novel Edgar, but he never actually reviewed it for the paper. I wonder who did. Except for her later novel The Fool Killer (1954), Eustis never wrote anything else in our genre. Our loss.

For anyone like me who began seriously reading mysteries in the Eisenhower era, the name of John Dickson Carr was then and still is one to conjure with. He’s been dead since 1977, but no one has yet come close to taking over his position as the premier practitioner of the locked-room and impossible-crime type of detective novel.

We never met but I remain eternally grateful to him not only for giving me countless hours of reading pleasure, but also for telling his readers that in a small way I reciprocated. In the last full year of his life he reviewed my first novel for his EQMM column (March 1976) and called it the most attractive mystery he’d read in months.

Since his death he’s been the subject of at least two major books: Douglas G. Greene’s biography The Man Who Explained Miracles (1995) and S.T. Joshi’s John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study (1990). Now those volumes are about to be joined by a third. James E. Keirans’ The John Dickson Carr Companion will run around 400 pages and include an entry for every novel, short story and published radio play in the canon and just about every important character in any of the above, not to mention sections on such subjects as Carr-related alcoholic beverages, automobiles, weapons, London landmarks and Latin quotations.

How do I know so much about this as yet unpublished book? Because I’ve been asked by the publisher (Ramble House) to run my aging eyes over the book in pdf form and make any corrections I think it needs. That, amigos, is Reason Four behind the absence of a February column. I don’t know precisely when the Companion will be ready for prime time, but my best guess is a few months from now.

I haven’t finished going over the entire book yet but there’s one Carr-related literary incident that I’m willing to bet Keirans doesn’t mention. To know about it you have to have read the published volume of the correspondence between the Russian emigre novelist Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) and the distinguished literary critic Edmund Wilson (1895-1972). Nabokov — or, as Wilson called him, Volodya — was fond of mystery fiction; Wilson — or, as Nabokov called him, Bunny — hated it.

In a letter dated December 10, 1943 and addressed to Wilson and his then wife, novelist Mary McCarthy, Nabokov indicates that he’d recently read a whodunit entitled The Judas Window. The title of course is that of the novel published in 1938 under Carr’s pseudonym of Carter Dickson, but Nabokov’s letter seems to indicate that he thought the book had been written by McCarthy.

“I did not think much of [it], Mary. It is not your best effort…. [T]hat lucky shot through the keyhole is not quite convincing and you ought to have found something better.†How could such a mistake have happened? Wouldn’t the Dickson byline have been on any copy Nabokov might have read? However it happened, you’d expect that either Wilson or McCarthy would quickly have corrected Nabokov’s misapprehension.

But in fact there’s not another word about the book anywhere in the correspondence, and the editor of the collection of letters, Prof. Simon Karlinsky, was unfamiliar with detective fiction and printed Nabokov’s words without comment. Somehow I wound up with a copy of the first edition of the correspondence (Harper, 1979) and wrote to Prof. Karlinsky with a correction. In the revised and expanded edition (University of California Press, 2001), both Carr and I are acknowledged in footnotes to the Nabokov letter.

Fri 7 Aug 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Ellen Nehr:

STUART PALMER – Cold Poison. M. S. Mill Co./William Morrow, hardcover, 1954. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club [3-in-1 edition], June 1954. Pyramid R-1040, paperback, 1964.

Miss Hildegarde Withers is the definitive little-old-lady sleuth upon whom many future spinster, schoolmarm, and librarian sleuths were based.

Her prominence on the mystery scene was ensured by a 1932 film based on her first adventure, The Penguin Pool Murder, starring Edna May Oliver; and the ensuing fourteen novels and short-story collections in which she is featured brought her even greater recognition.

Five other films, with a variety of female stars, reinforced the much-loved image of a snoopy, highly intelligent, eccentric woman who helps the police in their investigations.

In Cold Poison, Miss Withers has semi-retired (from her teaching position) to California, but old habits die hard — especially when the production manager of Miracle-Paradox Studios asks her to investigate the four un-comic, Penguin-decorated valentines promising death that have been received in the cartoon department where Peter Penguin’s Barn Dance is being animated.

Using the subterfuge of chaperoning Tallyrand, her French poodle who is modeling for the artists, Hildegarde starts by going to see the one practical joker among the suspects. She finds him dead of what turns out to be poison-ivy poison.

When she calls her old policeman friend, Inspector Oscar Piper, in New York, Oscar realizes that this case could very well tie in with one he couldn’t solve in New York four years before, so he flies to the Coast to assist.

He and Hildegarde become familiar with the world of cartooning and the various characters and their jobs — which takes up a good part of the book. When all clues are assembled, Hildegarde sets up a final confrontation in the screening room at the studio, even though she lacks the final clue necessary to confirm her suspicions.

During this showing of the valentines and Hildegarde’s attempt to compare them to sketches by members of the cartooning staff, an attempt is made to poison her coffee — and a little-known fact arises that helps her solve the case.

This entertaining case was Hildegarde’s next to last; her final appearance was in Miss Withers Makes the Scene (1969), which was begun by Palmer and completed by Fletcher Flora after Palmer’s death.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 7 Aug 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Ellen Nehr and Marcia Muller:

STUART PALMER – The Penguin Pool Murder. Brentano’s, hardcover, 1931. John Long, UK, hc, 1932. US softcover reprints: Bantam, 1986; International Polygonics, 1991; Rue Morgue Press, 2007. Film: RKO, 1932, with Edna May Oliver as Miss Hildegarde Withers and James Gleason as Police Inspector Oscar Piper.

In this novel, which introduced Hildegarde Withers to the mystery-reading public, Miss Withers takes her grade school class to the New York Aquarium, where one of her students sees a body floating in the penguin pool.

As soon as the police arrive, Hildegarde begins making suggestions; and after having another teacher take the students back to school, she insists on helping Inspector Oscar Piper by taking notes in shorthand (which she has studied as part of her hoped-for avocation as police assistant). Hildegarde takes time off from teaching to run around New York with Oscar until, with her guidance, the baffling case is solved.

This is a low-key introduction to one of the genre’s more likable investigative pairs. Hildegarde is typical old-maid schoolteacher: austere, sensible, and entirely out of patience with what she considers the police’s inefficient and bumbling ways.

Oscar, on the other hand, is your typical cigar-smoking cop: tough on the outside but thoroughly cowed by what he would never admit is a formidable woman. The friendship and affection that develops while they are investigating the strange death among the penguins — with Oscar doing the legwork and Hildegarde supplying insight — is one that continues throughout the thirteen-book series and numerous short stories.

(Hildegarde acts on the theory that years of dealing with children in the classroom make her an expert on devious behavior patterns in adults, too — and Oscar is eventually forced to admit she is right.)

At the end of this first adventure, Hildegarde and Oscar go off hand in hand to the marriage-license bureau; however, they must have changed their minds on the way, because they remain platonic — albeit fond — friends throughout the rest of the series.

Outstanding among the other Hildegarde Withers novels are The Puzzle of the Red Stallion (1936), Miss Withers Regrets (1947), and The Green Ace (1950).

Hildegarde’s shorter cases can be found in such collections as The Riddles of Hildegarde Withers (1947) and The Monkey Murder, and Other Hildegarde Withers Stories (1950), both of which are digest-size paperback originals published by Mercury Press.

A later series character, Howie Rock, is an obese, middle-aged former newspaperman who appears in Unhappy Hooligan (1956) and Rook Takes Knight (1968). The first of these novels makes use of Palmer’s unusual background as a circus clown for Ringling Brothers.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Bibliographic Update: Another collection of Miss Withers stories has been published since 1001 Midnights first appeared, and it’s one well worth your attention: Hildegarde Withers: Uncollected Riddles, Crippen & Landru, 2002.

Thu 6 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

STUART PALMER – The Puzzle of the Red Stallion. Bantam, paperback reprint; 1st printing, February 1987. Hardcover edition: Doubleday Crime Club, 1936; hc reprint: Sun Dial Press, date unknown (cover shown). British title: The Puzzle of the Briar Pipe. Collins, 1936. Film: RKO, 1936, as Murder on a Bridle Path (with Helen Broderick as Hildegarde Withers & James Gleason as Police Inspector Oscar Piper).

I’ve not seen the movie recently, which means not within the past 40 years or more, but the synopsis and the various comments on IMDB makes it sound as though the book was translated into film, amazingly enough, about as closely as it could be done.

When a young woman riding her horse through New York City’s Central Park is found dead on the ground, it is presumed at first that her horse threw her, but when schoolteacher Miss Withers finds a spot of blood on the horse’s upper leg, even Inspector Piper has to agree that something suspicious has happened.

And when more clues prove conclusively that the woman was murdered, there no shortage of suspects, including an ex-husband whom she had jailed for non-payment of alimony; her ex’s father; the stablehand whom advances she spurned; another fast-living type named Eddie for which the same goes; the obnoxious stable owner who’d love to get her hands on the titular horse; that lady’s meekish sort of husband; and more.

This is a good but far from great example of the 1930s concept of the comic crime novel, and no, you should not expect anything resembling good professional procedure on the part of the police and medical experts who are called in. In fact, quite oppositely, both are fairly inept at what they are supposed to do.

But what can you expect when the police allow an old maid, a spinster, if you will, to follow the head of homicide around on his cases, picking up and stashing away clues at her own discretion, running interference for him when he?s about to go off in wrong directions, and generally being in charge of the case, albeit of course strictly unofficially?

Comedy is a matter of taste, and in this case, it worked only intermittently for me. The was the sixth novel Hildegarde Withers was in, and by this time I think Stuart Palmer simply fired up the plot and let things cruise along on automatic.

There is some good detective involving pipes and the people who smoke them, and there is also the reddest of red herrings. You get the good with all of the pleasure of watching an author work up a fine case of deductive reasoning, and you take the bad with a small grimace of my goodness, did he really do that?

He does, and he did.

Sun 20 May 2007

As you may remember, Mike Grost and I recently exchanged some friendly comments after my

review of

Step by Step, the 1946 film starring Lawrence Tierney and Anne Jeffreys. The director, Phil Rosen, began in the day of the silent movies and was close to the end of his career when he made

Step by Step. The screenwriter for the film was noted mystery writer Stuart Palmer, author of the Miss Withers detective novels.

Mike has a long page of commentary about Stuart Palmer and his work at his own Classic Mystery and Detection website. If you’re a fan of Palmer’s, I invite you to go and read it first, and even if you’re not.

A recent addition to that page is a lengthy discussion of Step by Step, which Mike has agreed to allow me to reprint here. In his comments Mike not only compares Palmer’s writing techniques in the two media, print vs. film, but he also takes a look at Phil Rosen’s traits as a director, comparing some aspects of Step by Step with The Young Rajah, a silent film he made in 1922.

— Steve

Step by Step

Palmer’s last Hollywood film Step by Step (1946), is an entertaining comedy espionage-thriller. Palmer scripted, from George Callahan’s story. The tale has some elements in common with Palmer’s prose mysteries:

* The hero, an ex-Marine played by hulking Lawrence Tierney, bears some resemblance to Miss Withers — in personality, that is. (Miss Withers is frequently compared to horses, while he-man Tierney looks more like a gorilla.) Like Withers, the hero is a snoopy, comic, highly persistent amateur detective, who stumbles over suspicious circumstances, and butts in to investigate where he is not wanted.

* He has a comic but intelligent and helpful dog to whom he talks — Hildegarde will soon acquire her poodle Talleyrand in Four Lost Ladies (1949).

* The code is hidden in an unusual hiding place (inside the jacket). Palmer had written several mysteries about hard-to-find hidden objects: “The Riddle of the Dangling Pearl”, “Once Upon a Crime” and “Rift in the Loot.” Those prose short stories were puzzle plots, in which the reader had no idea where the object was till the solution of the story. In Step by Step, however, the viewer learns right away where the code manuscript is.

* The bad guys do lots of impersonation, reminding us that Miss Withers liked to impersonate people, and so do some of the villains in her stories, notably in “Rift in the Loot” (1955). Impersonation of sorts also turns up in some of Palmer’s Strange Person plots.

* The way that the senator, his secretary and chauffeur are all echoed and impersonated by spies who are a fake senator, secretary and chauffeur, perhaps recalls the symmetry that plays a role in some of Palmer’s stories.

* Some of Palmer’s mystery puzzle plots revolve around men who wear each other’s clothes: The Penguin Pool Murder (1931), “The Riddle of the Double Negative” (1947) and “Once Upon a Crime” (1950). In Step by Step, the hero wears the murder victim’s jacket. This plays a role in the thriller plot — but it is not the subject of a puzzle plot mystery, unlike Palmer’s prose fiction. The heroine also tries on the hero’s Marine uniform.

* A hammer keeps playing a role in the story, popping up again and again with new and different connections to events. This is a bit like the Palmer characters who are Mysteriously Involved, and who keep getting tied in to the mystery plot in new ways.

* The blinking light in the finale recalls the moving beams of light in Arrest Bulldog Drummond. Palmer perhaps thought that “telling a story with light” was a good approach to the film medium. Such use of light is also found in director Edgar G. Ulmer’s films.

One wonders if “B-13,” part of the spy code, is Palmer’s homage to John Dickson Carr’s radio play, “Cabin B-13” (1943).

The other members of the creative team also have personal elements in Step by Step. George Callahan’s use of electronic bugs by the spies recalls the even more unusual television jukebox in The Shanghai Cobra, for which he also wrote the story.

Director Phil Rosen was reduced in 1946 to low budget B-movies like Step by Step, but during the silent era he had worked on major films like The Young Rajah (1922).

* Rosen has Tierney doing much of his early sleuthing clad only in bathing trunks, in scenes that recall Rudolph Valentino in a swim suit rowing for Harvard in

The Young Rajah (Rudy wins the Big Race).

* Rosen doesn’t have a budget for the sort of opulent costumes seen in The Young Rajah, but he does have a large cast of men in every sort of unusual clothes: in addition to his shirtless hero, there is a doctor in whites, a true and false chauffeur, both in uniform, and more leather clad cops than you can shake a stick at. The cops have two different kinds of motorcycle uniforms. Such elaborate uniforms were also a tradition in Columbia Pictures B-Movies, such as the Boston Blackie films of the 1940’s.

* The retired Vermont sea captain in Step by Step might reflect the fondness Rosen showed for New Englanders in The Young Rajah.

Thu 26 Oct 2023

Posted by Steve under

General[9] Comments

From A Reader’s Guide to the American Novel of Detection (1993) by Marvin Lachman, and posted previously on the Rara Avis Internet group by Tony Baer:

The Shudders, Anthony Abbot

Charlie Chan Carries On, Earl Derr Biggers

Wilders Walk Away & Hardly a Man is still Alive, Herbert Brean

Triple crown, Jon Breen

The Junkyard Dog, Robert Campbell

Hag’s Nook, 3 coffins, crooked hinge, case of the constant suicides, Patrick butler for the defense, the burning court, John Dickson Carr

Kill Your darlings, Max Allan Collins

The James Joyce Murder & death in a Tenured Position, Amanda Cross

The Hands of Healing Murder, Barbara D’Amato

A Gentle Murderer, Dorothy Salisbury Davis

The Judas Window, The reader is Warned, The Gilded Man, She Died a lady, He wouldn’t Kill Patience & Fear is the same, Carter Dickson

Method in Madness & who Rides a Tiger, Doris miles Disney

Old Bones, Aaron Elkins

The horizontal Man, Helen Eustis

The case of the Howling Dog, …the counterfeit eye, ….lame canary, …perjured parrot, …crooked candle, …black eyed blonde, Erle stanley Gardner

What a Body!, Alan Green

The Leavenworth Case, Anna Katherine Green

The Bellamy trial, Frances Noyes Hart

The Devil in the Bush, Matthew head

The Fly on the Wall, Tony Hillerman

9 times 9, Rocket to the Morgue, H.H. Holmes

A Case of Need, Jeffery Hudson

Friday the Rabbi Slept Late, Saturday the Rabbi Went Hungry, Harry Kemelman

Obelists Fly High, C. Daly King

Emily Dickinson Is Dead, Jane Langton

Banking on Death, Accounting for Murder, Murder Makes the Wheels Go Rounds, Murder Against the Grain, When in Greece, Emma Lathen

The Norths Meet Murder, Murder Out of Turn, The Dishonest Murderer, Frances and Richard lockridge

Through a Glass Darkly, Helen mcCloy

Pick Your Victim, Pat McGerr

Rest You Merry, Charlotte MacLeod

Paperback thriller, Lynn Meyer

The Iron Gates, Ask For Me Tomorrow, vanish in an Instant, beast in View, Margaret Millar

Death in the Past, Richard Moore

Murder for Lunch, Haughton Murphy

The 120 Hour clock, Francis Nevins, Jr.

The body in the Belfrey, katherin Hall Page

The Puzzle of the Blue Banderilla, stuart Palmer

Remember to Kill Me, Hugh Pentecost

Generous Death & No Body, Nancy Pickard

Unorthodox Practices, Marissa Piesman

The roman Hat Mystery, the French Powder Mystery, The Greek Coffin Mystery, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, The Chinese Orange Mystery, Calamity town, Cat of Many Tails, Ellery Queen

Puzzle for Puppets, Parick Quentin

Death from a Top Hat, Clayton Rawson

The Gold gamble, Herbert resnicow

8 Faces at 3, Craig Rice

Strike Three You’re Dead, Richard Rosen

The Tragedy of X, The Tragedy of Y, Barnaby Ross

The Gray Flannel Shroud, Henry Slesar

Reverend Randollph and the wages of Sin, Charles Merrill Smith

Double Exposure, Jim Stinson

Carolina Skeletons, David Stout

Fer de Lance, The rubber band, too many cooks, some buried Caesar, the silent speaker, in the best families, the black mountain, the doorbell rang, a family affair, rex stout

Rim of the Pit, Hake Talbot

The Cut Direct, Alice Tilton

The Greene Murder Case, SS van Dine