Mon 7 Sep 2009

by MIKE GROST.

Rufus King’s last works were a series of short stories set among the rich in Miami and its environs; many of them were published by Ellery Queen in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Although King’s use of Miami has been compared to John D. MacDonald, it also recalls the Florida stories of Philip Wylie. In addition to setting, other Wylie-like features include an emphasis on botany and Florida plant life, amateur detectives who discover sinister conspiracies, and the use of international intrigue.

Three of the more interesting of these stories are discussed below.

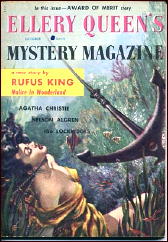

“Malice in Wonderland” (EQMM, October 1957) contains some of King’s most magical atmosphere and mise-en-scéne. The tale is written as a sort of sinister fairy tale, full of events that can be given a supernatural interpretation.

King used rich and brilliant color in these Miami stories, especially in his descriptions of deserts. In “Malice”, we see exotic ice cream dishes that are described in full color. By the way, “Malice in Wonderland” was originally the title of a 1940 novel by Nicholas Blake. When Ellery Queen first published King’s short story in EQMM, he thought the phrase would make a good title for the story, and he used it, with the permission of both Blake and King.

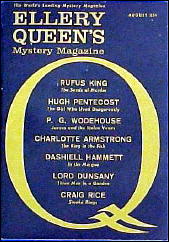

“The Seeds of Murder” (EQMM, August 1959) is an impossible crime tale. There are clues that allow one to deduce who the killer is, at least after you have figured out how the crime was done.

This is the paradigmatic detective situation in such Ellery Queen works as The Spanish Cape Mystery (1935). This story seems even closer to Queen than to Van Dine. It focuses on the sort of rich, eccentric, multi-talented extended family of adults that often pops up in Queen tales.

“The Faces of Danger” (EQMM, November 1960) is written in a partly summarized style. This style recalls, to a degree, that used by Ellery Queen in his Q.B.I. stories and parts of his Calendar of Crime.

However, King’s approach is less condensed than Queen’s. Queen used it to tell a whole story in less than ten pages, while King’s novella sprawls over forty. Both writers like to use the approach to invoke, and partially lampoon, the clichés of storytelling.

In both, there is a certain sophistication of tone, a suggestion of sophisticated satire on conventional plotting. There is the feeling in both writers in which a game is being played by the author. In this game, the author tries to come up with the “best” response by the characters to each new situation.

For example, a body might be discovered, and the next step in the story is tell what the characters are going to do. Sometimes this response is original, sometimes conventional. The more conventional responses are presented to the reader with irony, using a summarized statement to invoke the chief elements of the familiar situation.

Less familiar responses are sometimes contrasted with the clichés of fiction, to underline the originality of the situation. So a description will contain both its true content, and its opposite.

The whole effect is of a game the author is playing with the reader, challenging them to guess how the characters will behave in any new situation, suggesting a duel of wits between the writer and the reader over the most original response to any event in the plot.

This is in keeping with, but further extends, the basic active reading approach of most mystery fiction. In most mystery tales, the reader is not supposed to sit back, and just let the events of the tale wash passively over them.

Instead, the reader is challenged to deduce the true solution of the mystery at every turn. The reader, in turn, constantly monitors the author’s plot for logical consistency, and surprise. This sort of active readership is applied to every event in the mystery plot.

In Queen and King, this approach is extended not just to the mystery puzzle plot itself, but every fictional development in the story: the characters’ attitudes, responses to events, social conditions and backgrounds, police procedure, the romance subplot, details of the social milieu such as butlers and mansions, in short, every aspect of the story. This allows active readership as a universal response to the tale.

King always likes verbal fireworks in his tales; such an approach gives him many opportunities in that direction. It allows for an exuberant writing style, one filled with elaborate turns of phrase and much wit.

September 8th, 2009 at 7:22 pm

This is the first I’ve been able to see the remarkable cover painting for “Malice in Wonderland”. It goes well with the equally atmopheric story.

The cover of THE FACES OF DANGER, King’s last book, is a good tribute to a writer who loved the sea.

Re-reading the excellent reviews from 1001 MIDNIGHTS, it suggests I should pay more attention to Rufus King’s plotting skills in future readings. There is much to learn…

July 18th, 2010 at 2:43 pm

[…] Piece No. 13 (reviewed by Bill Deeck) Rufus King’s Florida short stories (by Mike Grost) Holiday Homicide (reviewed by Mike Grost) Design in Evil (reviewed by Mike Grost) […]