Tue 23 Oct 2012

Reviewed by Dan Stumpf (Book/Film): CONFESSIONS OF AN (ENGLISH) OPIUM EATER.

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews[8] Comments

Nowadays, weird movies are so numerous as to pass unnoticed; it is, in fact, common practice lately to layer a certain amount of weirdness deliberately onto quite ordinary films to increase their appeal to trendy movie-goers and boost the box office.

But in my youth, the truly weird movies were something subversive filmmakers got away with, mainly in the B-features when no one was looking. Hence, the old weird movies played at neighborhood grind-houses to audiences of uncomprehending kids and drunks, then on local TV stations at obscure hours of the morning, diced up with ads for used cars and the amazing veg-O-matic.

Hold that thought. I’ll get back to it.

The things I read, given world enough and time, begin to amaze me. A few weeks ago, f’rinstance, I found myself somewhere deep inside Thomas DeQuincey’s memoir (sensationally serialized in the London papers circa 1821-22) Confessions of an English Opium Eater.

This is not a book I’m going to recommend to lovers of Junkie or Musk, Hashish & Blood. The density of DeQuincey’s prose is such as will daunt most readers, and I don’t blame ’em a bit. Take one typical sentence —

— and you’ll see it takes a Sherpa guide to get through some of these passes, and the reader with any sense at all for brevity and clarity may justifiably fling deQuincey’s book across the room.

Imagine my surprise, then, when I found myself not just enjoying this thing, but actually pursuing the tale (such as it is) eagerly to its end. For those who can fight through the dense prose, Confessions holds some powerful bits of sheer writing: harrowing descriptions of starving in London; stark descriptions of beggars and streetwalkers going desperately down winding, shadowy streets; gaudy evocations of wild opium dreams, and even the odd bit of humor jumping out from hiding, as his advice on taking Opium:

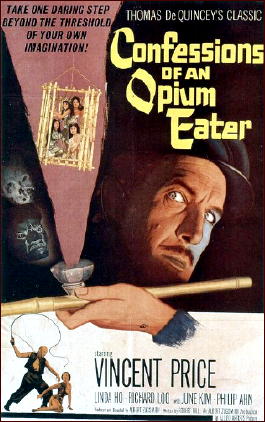

Now to return to that thought you’ve been holding, DeQuincey’s title, somewhat abbreviated into Confessions of an Opium Eater was used for a film completely unrelated (or almost completely; the hero’s name is Gilbert DeQuincey) to the book.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoRBNxuweP0

Released by Allied Artists (formerly Monogram) in 1962, produced and directed by that wild card of the Cinema, Albert Zugsmith (look him up) this was a cult film before there were cult films, a movie that emerges as simply weird for its own sake, rather than aimed at any particular audience. Spawned by a filmmaker known equally for his work with geniuses and for his own trashy bad taste, Confessions will easily boggle the mind of anyone unprepared for its tawdry neo-surrealism.

Vincent Price stars as a black-clad and bemused soldier-of-fortune charged with ending the Oriental slave trade in San Francisco, circa 1920s — an action hero if you will, and if the mantle seems to rest a bit awkwardly on his shoulders, he still bears it manfully, jumping from rooftops, hatchet-dueling with Tong assassins, freeing fair young maidens and trading repartee with the Dragon Lady — in short, everything you expect from a two-fisted hero, but done with a sardonic lyricism never seen outside this cheap little movie, with lines like: “They say in every drunkard there’s a demon, in every poet a ghost. So here am I ghost and demon…”Â

There are other surprises along the way, including an oriental den of iniquity filled with several hundred doors, sliding panels and secret passages; a tiny slave girl locked in a cage who turns out to be a jaded and diminutive old woman; an extended slow-motion dope-dream fight sequence, and an ending that made me doubt my senses. In short, this is the goods: a genuine Old Weird Movie and like nothing else you’ll ever see.

October 24th, 2012 at 12:20 am

Dan:

For whatever it is worth, and I suspect not much, but in 1966 I had lunch at the Paramount commissary with Albert Zugsmith, my guest, and later a sauna at his sumptuous home, as his guest. He was round and strong and an altogether nice fellow. However the conversation was at a surprising level. He was aiming at getting projects such as the one you describe off the ground. The other people I knew might have ended with something like the Price picture but their aspirations were in an altogether different direction. In any case, I could not do business with him, but liked him for his warmth and generosity.

October 24th, 2012 at 10:56 am

A very interesting review. I read some of De Quincey’s books in German translation and enjoyed them, but unfortunately I have not read “The Confessions of an English Opium Eater”. I should like the movie as well.

October 25th, 2012 at 4:52 pm

A very appropriate author for this site.

“If once a man indulges in murder, very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination.”

From his essay, “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts.”

October 26th, 2012 at 9:14 am

Vincent Price as Action Hero. It does amuse. I’ll get over to YouTube and check it out. This is one reason why I visit Mystery*File, to see what gems and oddities are being unearthed. And Barry Lane’s comment on Zugsmith was interesting. Nice to know he was a pleasant sort. According to Wikipedia, Zugsmith’s older sister Leane was a “leading proletarian novelist” in the 1930’s.

October 26th, 2012 at 10:27 am

I’ve been neglectful all week long in pointing out that OPIUM EATER, the film, has been reviewed once before on this blog, and then by David L. Vineyard:

https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=1274

October 26th, 2012 at 12:07 pm

Vincent Price as an action hero is not surprising. After all, he played The Saint for years. On radio rather than film, but still….

Ron Smyth

October 26th, 2012 at 12:40 pm

Had no idea Price played the Saint on the radio. Had no idea that the Saint was ever a radio show.

I know Price more for his campy/fey stuff, like those Brady Bunch episodes in Hawaii.

February 22nd, 2018 at 4:34 am

Watched this one today. It’s a very strange film. It’s not quite Bunuel — okay, it’s nowhere near Bunuel – but it’s a largely plotless film that exudes strangeness, atmosphere, sweat and sin. Price’s lyricism in dialogue is probably the most memorable part