Mon 21 Jun 2010

A Review by David L. Vineyard: PETER DICKINSON – A Summer in the Twenties.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[4] Comments

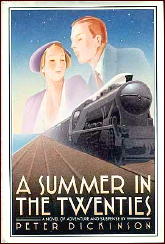

PETER DICKINSON – A Summer in the Twenties. Pantheon, US, hardcover, 1987. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1981.

The year is 1926, and the Twenties are Roaring with flappers and social conscience and colliding with the death of the Victorian era and Red scares about rising Bolshevism. That’s the background for Peter Dickinson’s A Summer in the Twenties.

This one is more a thriller than a detective story though Dickinson was one of the bright lights of the late flowering of the fair play detective story. He and Robert Barnard almost single-handedly revived the genre injecting humor and style as well as real insights into character and action and in many ways extending the traditions begun by Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Michael Innes, even as P.D. James and Ruth Rendell were taking the genre in their own directions.

Dickinson’s best books were those featuring Superintendent Jimmy Pibble, and his Poison Oracle — in which the detection is done by a chimp who has been taught to communicate in a private zoo in the curious palace of a desert sheikdom — was chosen by H.R.F. Keating for his Crime and Mystery Stories The 100 Best Books (reviewed by Marv Lachman here ).

Thomas (Tom) Hankey is the hero of this one, the son of Lt. General Lord Milford, and a product of the privilege and wealth of the upper classes at a time when that meant more than money. At the novel’s start he is in the South of France pursuing the beautiful Judy Tarrant, another product of the same class.

But this idyll is cut short when Tom is summoned home by his father. A crisis is brewing in England, one that borders on revolution — the General Strike of 1926.

For those unfamiliar with the General Strike, it was an attempt by the British working class to shut down transportation and other industry in England to show both their importance to the country’s economy and protest social injustice, triggered by a lockout of coal miners. Instead it inspired paranoia in the upper and middle classes and the government, with memories of the recent Russian Revolution still fresh and the Tory government anxious to break the back of the Trades Unions.

While there were certainly some radicals on the left with visions of a revolution, that was far from the aims of the mass of strikers — but in this case appearance trumped reality. It became a defining moment in the class war in England and inspired the plots of many a thriller in the Sydney Horler and Sapper class. Dennis Wheatley’s first Gregory Sallust novel Black August was a Wellsian variation inspired by the General Strike.

And true to the spirit that would carry England through the Blitz, the upper and upper middle class rallied, manning the vital jobs of the working class and keeping the country going. Whatever your politics, it was a splendid effort mindful of WW II when even the then Princess Elizabeth was in uniform driving a staff car.

That’s why Tom’s father has called him home, to train as a volunteer engineer on the railway:

His father has more sympathy for the miners than the owners, but the General Strike is anathema to him.

Tom is quickly dispatched to the slums of Hull, a mining town unlike anything in his life experience. There his wish to do his duty clashes with his innate sympathy for the workers and his sense of decency and fair play. Confronted by bullies and violence on both sides, gangs of hooded men with guns, he finds merely doing the right thing to be a challenge, and his feelings for Judy Tarrant are soon tested when he meets fiery Kate Barnes and a passionate agitator.

What makes reading Dickinson a pleasure is that the characters are well drawn and above all human. They make mistakes, have prejudices on both sides of the question, and manage to change, grow, and rise to the occasion as needed. Tom, Judy, and Kate all grow. He is also the brightest of writers, capable of real humor and rare intelligence.

Though there is little mystery element there is a good deal of action some railway lore and the growth of the main characters, especially Tom …

This being Dickinson there is a killer and a mystery resolved, though a minor one, but as a portrait of a unique time and a picture of good people trying to resolve the differences that divide them, coming together for a common good, and facing the very real class divisions that separate them A Summer in the Twenties is a solid smart read.

If you don’t know Dickinson, he is well worth meeting. He took up writing at age forty after seventeen years as an editor at Punch. He was successful both as a children’s author and a mystery writer, winning a Gold Dagger from the Crime Writer’s and the Carnegie Medal for his children’s books, and his books, including King and Joker, The Lively Dead, One Foot in the Grave, Walking Dead, The Lizard in the Cup, and Skin Deep are all good examples of his many virtues.

Previously reviewed on this blog:

The Lively Dead (by Steve Lewis)

June 21st, 2010 at 8:21 pm

David

This book by Dickinson, which is new to me, is not in Al Hubin’s CRIME FICTION IV, and from your review, I think it should be, even if with a hyphen, indicating only marginal crime content.

It may be difficult to read, due to the small size of the cover image, but a blurb on the front calls the book “A Novel of Adventure and Suspense.”

What do you think? Is this a book that should be called to his attention?

I also love the cover art. That’s a nice looking train. It may be too stylized to be authentic, but it does look nice.

— Steve

June 21st, 2010 at 8:46 pm

This clearly belongs in Hubin, and maybe without the hyphen since there is a murder and a bit of detection involved in it as well as sabotage and armed men wearing hoods. Someone called it the kind of thing Bulldog Drummond might have gotten up to with brains.

Granted it isn’t primarily a detective story, but it is as the cover says a novel of adventure and suspense — and a damned good one too.

June 22nd, 2010 at 6:34 am

Yes, this belongs in Hubin. I’m surprised to hear it’s not in there. I like Dickinson a lot but haven’t read this one, though I started it once before getting sidetracked.

June 22nd, 2010 at 3:46 pm

This one is a bit different from Dickinson’s general work — longer, and not principally concerned with crime, although there is a murder and the hero to some extent solves it, and the revelation of who the killer is remains key to the resolution of the novel. The atmosphere of violence and danger from both sides is well developed and it certainly fits into the thriller category if less into the classic mystery like most of Dickinson’s adult output.