Wed 2 Oct 2013

Mike Nevins on CRAIG RICE, CLYDE B. CLASON and MORE.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Columns , Reviews[7] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

The latest golden oldie I decided to revisit in my golden years is 8 FACES AT 3 (Simon & Schuster, 1939), which I first read in the summer of 1964, just before I entered law school. Craig Rice (1908-1957), one of the most popular female mystery writers of her generation, entered the genre with this novel, along with alcoholic criminal defense lawyer John J. Malone, drink-sodden talent agent Jake Justus, and ever-inebriated heiress Helene Brand, who would become Mrs. Jake in future outings.

Amid copious shots of booze the trio probe the stabbing death of vicious old Chicago dowager Alexandria Inglehart, whose murderer also made all the beds in the Inglehart mansion and (dare I say it?) took the time to stop all the clocks in the house at 3:00. The plot is marred by logical holes and legal howlers — sorry, Ms. Rice, but no court would enforce a will provision nullifying an outright bequest if the recipient marries after the testator’s death — and the solution is surprising but only mildly fair and a bit hard to swallow.

What I found most striking about this novel is the interweaving of some all but noirish sequences with scads of drunken escapades. Rice seems to think that hoisting a few while driving along Chicago streets that have turned to sheets of ice is the height of hilarity, although when held up against the later exploits of Malone and his buddies this one is a model of rationality and sobriety. The critics who have likened Rice’s world to Hollywood’s screwball comedies of the Thirties knew what they were talking about.

How do I know precisely when 8 FACES first came into my ken? Because, rummaging in my file cabinets between sessions with Rice’s madcap protagonists, I discovered an old notebook containing comments on the mysteries I had read back in the Sixties and Seventies. Dozens of these clumsily written paragraphs became the rough sketches for material that wound up in various essays of mine, like the ones on Cleve F. Adams, William Ard and Milton Propper; many others have been seen by no eyes but my own.

Among the subjects of the latter is Clyde B. Clason (1903-1987), who wrote ten well-regarded classic puzzle novels in the 1930s and early Forties before giving up the genre permanently. Protagonist of all ten is Professor Theocritus Lucius Westborough, a little old man whose day job is teaching classical languages and literature but whose true forte is solving bizarre murders.

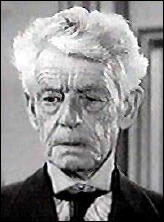

Anyone remember an actor named Cyril Delevanti? He was a dried-up old prune who, usually uncredited, played clones of himself in dozens of movies, including Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux and Limelight and John Huston’s Night of the Iguana, and a hundred or more episodes of TV series like Gunsmoke, Perry Mason, Have Gun Will Travel, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Ben Casey and The Twilight Zone.

For me Delevanti is the living image of just about every little-old-man detective character, including Henry the Waiter in Isaac Asimov’s Black Widowers stories and, of course, Clason’s Professor Westborough. In my mind’s ear I can almost hear Delevanti murmuring “Dear me†as Westborough does times without number.

Of Clason’s ten novels I’ve only read three, the earliest being THE DEATH ANGEL (1936). On a visit to a friend’s estate in southern Wisconsin while local farmers are staging a violent milk strike, Westborough is deputized by the sheriff after his host first receives a threatening note signed “The Firefly†and then vanishes.

The professor investigates the series of attempted murders that follow and encounters two clever ways of setting up a perfect alibi and perhaps a bit too much information about archery, mushrooms and the theory of electricity. Clason‘s characters tend to evade, drawl, growl, grunt, explode, supply, venture, persist, ejaculate and flare, but most of his said substitutes aren’t too outrageous and his plot convolutions are spectacular.

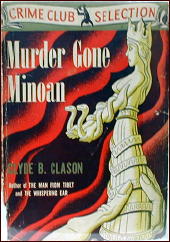

The later Westborough novels tend to revolve around ancient or exotic settings. MURDER GONE MINOAN (1939) takes place on a private island off the California coast, owned by a Greek-American department-store tycoon with a phobia about the imminence of another Depression and a passion for the millennia-old Cretan civilization. When a priceless Minoan religious image disappears from the tycoon’s Knossos-like palace, Westborough is asked to investigate and encounters a mess of amorous intrigues and two murders apparently committed by a devotee of the ancient Cretan snake goddess.

The parts of the story told in transcript and document form are neatly handled, but the mind boggles at the amount of physical action this frail 70-year-old academic takes part in, and the solution he comes up with is hopelessly unfair (except to readers who can tell whether a particular classical quotation comes from the Iliad or the Odyssey). The said substitutes, plus a small army of exclamation points, are piled on with a vengeance.

In GREEN SHIVER (1941), Clason’s tenth and last detective novel, the place and time are southern California in early 1940. As in MURDER GONE MINOAN, the first crime is the theft of an exotic religious image, this time a jade Taoist goddess which vanished from the Oriental palace of an oil widow during a public exhibition of her treasures to benefit Chinese war refugees.

Westborough, who is suddenly gifted with expert knowledge of ancient China as well as Greece and Rome, is offstage far more than in earlier Clasons but quickly gets involved in a bizarre double murder with occult overtones. The clumsy plot depends on an unplanned perfect alibi, but the Sino-Japanese war background is well evoked and Clason’s knowledge and love of Chinese philosophy and culture enliven every page.

Have I been a little unfair to Clason? According to a slew of experts — Robert Adey, Jon Breen, Bob Briney and Randy Cox, just to name a few from the early letters of the alphabet — by far the finest of his ten novels is THE MAN FROM TIBET (1938), which I’ve never read. If I ever come across a copy, I’ll be sure to write it up in this column.

In Clason’s MURDER GONE MINOAN, Westborough satisfies himself that a man claiming to be a fellow classics professor is an impostor by quoting a verse apiece from the Iliad and the Odyssey and not being corrected when he attributes each verse to the wrong epic poem. Somehow this incident brought back memories of other mysteries where the detective character used his specialized knowledge in the same general way.

Perhaps the best known is found in “The Blue Cross,†the earliest exploit of G.K. Chesterton’s most famous character. At the climax Father Brown explains to the thief Flambeau, who is impersonating a priest, how from their dialogue he knew the other was a fake. “You attacked reason. It’s bad theology.â€

One of my favorite scenes of this sort — largely because it doesn’t require reader familiarity with specialized subjects like Greek poetry or Catholic theology — occurs in Rex Stout’s 1946 novelet “Before I Die.â€

Nero Wolfe is having dinner with a young man who claims to be a third-year law student. “I hope…that you are prepared to face the fact that very few people like lawyers,†Wolfe says. “I don’t. They are inveterate hedgers. They think everything has two sides, which is nonsense. They are insufferable word-stretchers. I had a lawyer draw up a tort for me once, a simple conveyance, and he made it eleven pages. Two would have done it. Have they taught you to draft torts?â€

“…Naturally, sir, that’s in the course,†the young man replies. “I try not to put in more words than necessary.†That, as Wolfe explains at the denouement, was the tipoff. “A tort is an act, not a document, as any law student would know. You can’t draft a tort any more than you can draft a burglary.†“Before I Die†is one of the clumsiest of all the shorter Wolfe exploits but that single moment keeps it green in my memory.

Editorial Notes: My review of Murder Gone Minoan can be found here. Curt Evans’ review of 8 Faces at 3 can be found here.

October 3rd, 2013 at 4:37 pm

For some reason I cannot remember ever recommending anything by Clyde B. Clason and since I cannot find any of his books on my shelves (though I once owned some of them) I cannot easily do the necessary research. But if Mike Nevins said I did it must be so.

October 3rd, 2013 at 5:39 pm

I never argue with anyone’s personal assessment, certainly not Mike Nevins, but I suspect political correctness is showing its head here and in several reviews I’ve read lately complaining about the lack of realism in the screwball school — especially about drinking.

Seventy years ago drinking was considered funny, and bright witty heroes had been imbibing gallons of booze ever since Bulldog Drummond. Nick and Nora Charles made it de rigueur, and soon barroom floors were littered with private eyes, lawyers, and reporters. Compared to Nebel’s Kennedy most of them were teetotalers, including the Justus’s and Malone.

If you want logic don’t read anything from the screwball school, and if you want reasonable sobriety — boy are you in the wrong sub-genre. No one ever claimed Craig Rice was a master of suspense or logic — but I still find her bright and funny (especially with Stuart Palmer) even if I have to detox after every book.

October 4th, 2013 at 3:33 am

As far as I know Craig Rice’s life ended in misery because of her long lasting alcohol-abuse.

October 4th, 2013 at 4:04 pm

I was once considered to be something of an authority on Craig Rice. I agreed to write an essay about her works for a reference book and acquired copies of her books as research material. I recall finding them entertaining and the current discussion may send me back to some of them to refresh my memory.

October 5th, 2013 at 11:02 am

My favorite “the clue lies in specialized knowledge” ‘tec story is one in which the trope is reversed: in (if I recall correctly) one of Asimov’s “Black Widowers” story the giveaway that the villain is only impersonating an American and is not himself one lies in said villain’s display of a minimal knowledge of and interest in cricket. (I’m afraid that as a Yank with at least a bit of knowledge and interest in cricket myself I would not have fared well in that scenario, so I’m glad I’m not fictional.)

October 6th, 2013 at 9:08 pm

My favorite specialized knowledge — or ability — mystery is “Tarzan’s Jungle Mystery” where the jungle Lord solves the case by smell, not far off the short where Lord Peter solves one based on a wine’s bouquet.

October 7th, 2013 at 3:31 pm

Craig Rice admitted somewhere (the Time magazine interview?) that she often never knew which character would be the murderer until she wrote the final pages. She made it all up as she went along. Isn’t the whole point of her books that they’re utterly wacky and have little to do with real life? How can Mike love Keeler so much and then denigrate Rice for the same approach to creating mystery plots?

Though I don’t think Mike is being PC in his criticism of the alcohol soaked “hilarity” I have to agree with David about anyone who tends to take that stance on old-fashioned farce with funny drunks. Similarly, I always roll my eyes when I read young people reviewing movies on their blogs and writing a few chioce words (ever so self-righteously) about how awful a movie is because everyone smokes too much.