Thu 7 Jun 2007

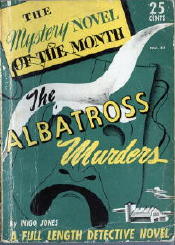

INIGO JONES – The Albatross Murders

The Mystery Novel of the Month #33; digest-sized paperback reprint, 1941. Hardcover First Edition: Mystery House, 1941.

Beginning with what’s known so far about the author, here’s a quote from Bill Deeck’s long-awaited reference book on lending library mystery publishers, Murder at 3 Cents a Day (Battered Silicon Dispatch Box):

Some detective work is therefore in order. The actual title of the book appears to be 50 Best American Short Stories 1915-1939, and one can find a complete list of the contents on the Internet, including all fifty authors.

This narrows it down, but not enough, unless authors like Erskine Caldwell, J. P. Marquand, and Dorothy Parker can be eliminated, and they probably can. But there are enough unfamiliar names there (Robert Whitehand, I. V. Morris, Lovell Thompson and a host of similar others) that at the moment, I cannot tell you that I have proceeded any further than this.

While I am presuming that the first name Inigo denotes someone of the masculine gender (about which see below), it cannot obviously be presumed that the person behind the pseudonym is equally masculine.

If by chance it is a clue to you (but not to me) that there are two Inigo Jones’s listed online at the wikipedia website, let me know. The first is considered the first significant English architect (1573-1652), while the second is a descendant of the first, one Inigo Owen Jones (1872-1954), who is noted as having been a well-known meteorologist and long-range weather forecaster.

More clues may arise from the settings of Inigo Jones, the detective story author. The Albatross Murders takes place in Shrewsbury, a small New England town, the mystery centering around the troupe of actors plying their trade in a two-months-long summer theatre. (No state is named; only New England. While no actual state name is mentioned, it had the distinct feel of Connecticut or western Massachusetts to me.) Doing the investigatory honors is Inspector Sebastian Booth.

Jones’s earlier book, The Clue of the Hungry Corpse (Arcadia House, hc, 1939; Mystery Novel of the Month #11, digest pb, 1940), takes place in New York City, and the detectives of record in that book were Lieutenant Blanding and Headquarters Detective Barry Linden, thanks again to Bill Deeck’s book. Which I admit doesn’t give us a lot more to go on, except to suggest that the author was familiar with both small town and big city American life, New England and New York City style. (I’d have eliminated Erskine Caldwell on this basis, if I hadn’t already.)

So who Inigo Jones was is a mystery as yet unsolved. There’s also, I go on to say, at last, an equally interesting case to be solved in The Albatross Murders as well – that of an actor being shot to death on stage with a gun loaded only with blanks, and in full sight of 500 people. More? It is later discovered that the bullet is not in the body, nor is there an exit wound.

There is a lot of back stage rivalry between the players – hardly unexpected, as such rivalries always seem to exist in such affairs – and in terms of both quantity and quality, there is certainly more than enough, and they are substantial enough, to keep the story going purely on the behind-the-scenes business alone. But adding some additional momentum to the tale, the local townspeople have their own secrets as well, and the events that occur after uncovering them turn especially nasty very quickly. The double combo gives Inspector Booth about as much as he can handle, or wants to.

There was a certain amount of crudity, I thought, in the detective’s initial approach. Chapter IV is twelve pages long and consists of nothing more (or less) than a re-creation of the murder, with all of the players in their places, and the body of the victim still lying uncovered on the floor.

But (and again, if this is a clue to the person behind the pen name, let me know) the author knows his way around backstage, and his detective character is no mean slouch at reasoning things through. Let me quote one paragraph from page 43, to allow you to see, I believe, for yourself:

Yes, yes, I know. Some of you are yawning already, and so was I for a while, but by page 108 the dialogue between the characters had become almost lyrical, the repartee flowing both easily and wittily, with Booth always firmly centered at the focal point. The method of the murder is clever enough, although highly unlikely, and with no perhaps about it. But one could say that of the Queen effort commented on a short while ago, couldn’t one?

Other than that, there’s really no comparison. In the final analysis, Jones’s effort comes up far short in comparison with that previously reviewed and totally superb, multi-faceted Queenian extravaganza. But even though The Albatross Murders is a minor league effort, it definitely has its pluses as well as minuses, making totally valid the final note I wrote myself – I always write comments to myself while reading – for this is what I said, somewhat in surprise, I have to admit, after the book and I got off to such a rough start together: “Not bad after all.”

And please take that statement for all that it’s worth. You can take it to the bank, deposit it, and count on it.

June 9th, 2007 at 1:56 pm

Steve:

Excellent piece on the Jones novel. Your summary comments pretty much match my own reaction to the novel: minor, not wholly believable, but readable and well written. The same is true of THE CLUE OF THE HUNGRY CORPSE. Whoever Jones was, he or she may not have been such-a-much as a mystery writer, but his/her prose is certainly a cut or two above that of most lending library authors of the period.

Thought you might like to add scans of the hardcover editions of both books to the article; they’re attached.

Best,

Bill

>> Thanks for both your comments and the cover scans, Bill. I’ll use the latter in a separate blog entry, though, and not this one, if I may. I’ll get them posted soon, I hope. –Steve

June 9th, 2007 at 3:00 pm

[…] As far as my comments about the pseudonymous Inigo Jones are concerned, nothing more has been learned than was stated in my review of his/her second mystery novel, The Albatross Murders. […]

December 6th, 2009 at 7:48 pm

[…] of this blog may remember that I reviewed this book several years ago. Check out my comments here. (All in all, I agree with Bill. This is not surprising, as Bill was seldom […]