Wed 30 Nov 2016

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: THE 39 STEPS (1959).

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews[4] Comments

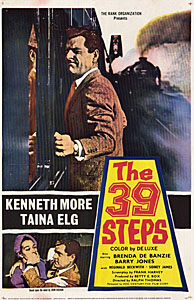

THE 39 STEPS. Rank Films, UK, 1959; 20th Century Fox, US, 1960. Kenneth More,Tania Elg, Barry Jones, Brenda de Banzie, Reginald Beckwith, James Hayter, Faith Brook, Dunacan Lamont, Jameson Clark, Sidney James. Screenplay by Frank Harvey, based on the novel by John Buchan. Directed by Ralph Thomas.

This color almost scene-for-scene remake of the 1936 Alfred Hitchcock classic has many things to recommend it, and had there been no film of the book by the master would stand as the best version of the story committed to film. Four films of the classic novel of escape and pursuit by John Buchan have been made including a slightly more faithful to the book version with Robert Powell and a version done for PBS. The Powell has things to recommend it, less so the PBS version. Not too long ago Jonathan Demme was thinking of doing yet another adaptation of the book.

Of course, Hitchcock himself remade it at least twice using the essential story from his own film, once as Saboteur with Robert Cummings and once more as North By Northwest with Cary Grant. For all the changes, both are variations on the same theme and plot. With the possible exception of “The Most Dangerous Game,†The 39 Steps may be the most borrowed plot in film and modern genre fiction. Even Bob Hope’s My Favorite Blonde owed much to it, including the presence of Madeline Carroll.

This version produced by Betty Box, opens with Richard Hannay (Kenneth More) footloose and at loose ends in London. In the park he encounters a Nanny (Faith Brook) and tries to return a rattle dropped on the ground only to be rebuffed. Still trying to return the rattle he saves her from nearly being run down by a car and ends up with the pram, which had no baby in it, and her purse with no identity but a gun and tickets to a music hall performance that night at the Palace (and that’s a fairly placed clue for the handful unfamiliar with the film versions).

The Nanny shows up, and promises to tell him the story behind the empty pram, but only after they watch Mr. Memory (James Hayter), a little man with a prodigious memory for facts. They go to Hannay’s flat, where she reveals she works for the government and is being hunted by a spy ring led by a man missing the top joint of his little finger. Something important about a military project is being smuggled out of England and it has to be stopped (the classic Hitchcockian definition of a McGuffin, that exists only to move the plot forward).

Hannay goes to make tea and while he is doing that, the two men (Duncan Lamont and Jameson Clark), who tried to run her down earlier and who have followed her to Hannay’s flat, kill her with a dagger Hannay brought back from his adventures (in the book he is an engineer from South Africa, in the Hitchcock he’s Canadian, and here he appears to have been connected with the Foreign Office though not as an agent).

He knows the police will never believe him and the two killers are waiting outside in case he tries to leave. His only hope is to follow the few clues Nanny gave him and go to Scotland and try to see the important man she named.

Aside from the color, what sets this apart from the Hitchcock classic is its on location filming. Some spectacular shots, narrow misses, and eccentric characters (shopworn medium Brenda de Banzie and her cuckold husband Reginald Beckwith), a few new bits including Hannay asked to speak at a girls school rather than a political meeting as in the book and first film (a scene ‘borrowed’ and set in a nudist meeting in the film of Irving Wallace’s The Prize, another Steps influenced thriller), all add to the mix that made the first film so charming and this one a worthwhile remake.

If nothing else, the location color shooting expands the films feel for Buchan country, something suggested by a few scenes in the original.

Along the way Hannay meets Miss Fisher (Tania Elg), who is traveling with a group of school girls, who doesn’t believe a word he says, but has seen and knows too much, ending up handcuffed to him as he tries to reach London and discover just where and what the 39 steps are (this version does restore the original meaning of the steps of the title even if we never see them).

The cast is first rate, but it is More’s film, and like Robert Donat before him, the success depends greatly on his charm and abilities as a light comedian as much as a dramatic actor. Elg does quite well, but lacks the cool Hitchcock blonde demeanor of Madeline Carroll. It isn’t her fault, even Deborah Kerr had trouble recreating icy Carroll’s beauty in The Prisoner of Zenda scene-for-scene remake. Barry Jones (Brigadoon, Seven Days to Noon) is especially sinister as Professor Logan who exudes charm and threat with the same soft tones.

Sidney James, Reginald Beckwith, and James Hayter all bring their usual skills to bits in the film, as does Brenda de Banzie as a phony medium half convinced of her own con and attracted to all the wrong men. Ralph Thomas was always a competent director and often more, and screenwriter Frank Harvey not only wrote or co-wrote some of the best films of the period but was a first class novelist as well (The Mercenary).

Hitchcock’s film is the classic, and there is no suggestion this is anything but a shadow of that, but it is a strong and quite entertaining shadow, and as the first version of the story I saw, it has some pride of place for me. It served as my introduction to the works of John Buchan and to Kenneth More, and both have served me well in terms of entertainment over the years.

The 39 Steps has been adapted to four films, radio, the stage (a major hit on Broadway and London’s West End), comic books, appeared as a serial in Argosy, and audiobooks. The book is a recognized minor classic (major in the mystery genre), and Alfred Hitchcock’s film a classic in itself.

This version may not reach that high bar, but it does have charm, excitement, wit, and attractive leads in an entertaining film, and that’s not such a low bar to achieve for any film, especially a remake.

November 30th, 2016 at 7:33 am

My comments on this film, as well as the 2008 made-for-British-TV version, can be found here:

https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=13416

November 30th, 2016 at 6:30 pm

There’s also a riotous adaptation for the stage.

November 30th, 2016 at 6:37 pm

My friend Paul has recommended the play to me as well. I’ve had a couple of chances to see it, but I’ve muffed it every time. Maybe next year!

November 30th, 2016 at 8:33 pm

The BBC radio dramatization of this, GREENMANTLE, and MR. STANDFAST is first rate, aided by having the same cast and usually played as a complete series.