Tue 8 Feb 2011

by Francis M. Nevins

At the name of Lee Thayer, most mystery fans draw a blank, but in other quarters it’s still well remembered. Emma Redington Lee was born in Troy, Pa. on April 5, 1874, studied at New York City’s Cooper Union and Pratt Institute, and got a job as an interior decorator (which in those days meant a painter of murals for the homes of the wealthy) at New York’s Associated Artists in 1890.

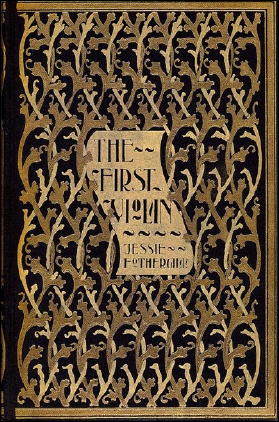

Some of her work was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 when she was still in her teens. Two years later she and Brooklyn architect Henry W. Thayer co-founded Decorative Designers, a firm which in the days before dust jackets produced binding designs, interior illustrations and the like for various New York book publishers. [An example of her work can be found at the end of this post.]

Lee and Thayer were married in 1909. The female partner is credited with having invented a method of using a split ink roller for printing color gradations on book bindings. Decorative Designs was first based in New York but migrated to Chatham, N.J. in 1921 and was dissolved, along with the partners’ marriage, eleven years later. Henry Thayer’s ex-wife called herself Lee Thayer for the rest of her life, probably because it was the byline on her detective novels.

Her first whodunit, The Mystery of the Thirteenth Floor, was published in 1919, when she was 45, and she continued turning out one or two books a year for well over four decades, a total of 61 titles.

All but one of them featured debonair red-thatched private sleuth Peter Clancy, who in Dead Man’s Shoes (1929) was joined by the intolerable imperturbable Wiggar, a Jeeves clone with an endless supply of scintillating bons mots like “Oh, Mr. Peter, sir!â€.

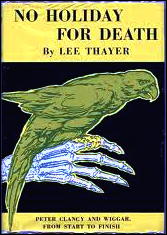

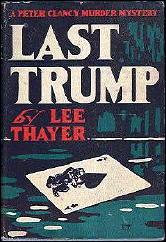

The union between master and valet lasted much longer than many marriages including Thayer’s own. She always thought of writing as a sort of sideline and kept her hand in as an artist by designing the dust jackets for all but the last three of her novels, several examples of which can be seen illustrating this column.

That she never became a household name is demonstrated by her only TV appearance. What’s My Line? was a popular CBS game show whose regular panelists (Arlene Francis, Dorothy Kilgallen and Bennett Cerf) were challenged to guess the occupations of various guests.

At the time of her appearance, May 11, 1958, she was 84 years old. Subsequently the program used her photograph in promotional ads: “This sweet little elderly lady writes blood-curdling murder mysteries!†Her last novel, Dusty Death, came out in 1966 when she was 92.

I know nothing about book design, but Thayer still seems to be highly regarded in that field. More than two dozen boxes of her Decorative Designs work are archived at UCLA, along with interviews taped very late in her life in which she reminisced about the firm’s work.

As a mystery writer she’s almost completely forgotten, and perhaps that’s the way it should be, because by ordinary standards there’s very little to recommend her. Feeble plots, clumsy writing, laughable characterizations, elephantine pace, zero fairness to the reader: you name the fault and Thayer’s books have it in spades.

Maybe it’s for this reason that I find in her what novelist and playwright Ira Levin told me he found in John Rhode: the perfect writer to take to bed. (Get that filthy thought out of your minds this instant!) But there are certain recurring elements in her novels that come close to qualifying her as an auteur.

One of these is the apocalyptic denouement. Whenever Peter Clancy has solved a murder to his own satisfaction but has no evidence that will stand up in court, God himself steps into the breach, striking the killer down from on high, while Thayer’s rhetoric swirls and squalls around and kicks up a furious storm.

In Accessory After the Fact (1943) it’s the founder of a quack religious cult who gets the treatment. The same furious deity strikes down totally secular villains in Out, Brief Candle! (1948) and Still No Answer (1958) and in who knows (I almost wrote God knows) how many Thayer novels I’ve never read.

Another Thayer hallmark is the off-the-wall crime method. Ransom Racket (1938) climaxes with Clancy’s reconstruction of a child-kidnapping: the gangsters drove a steam shovel up to the house, aligned the scoop with the baby’s upstairs bedroom window, stuffed the kid in the scoop and drove off undetected. (This is the book where Thayer writes “It was as dark as the inside of a cow†with a perfectly straight face.)

In Accident, Manslaughter or Murder? (1945) the victim is skating across a frozen lake on a moonless night, followed by the murderer in an iceboat which apparently makes no noise. Murderer maneuvers boat behind victim, swats him across the butt with an oar and propels him into a thin patch where the poor schmuck breaks through and drowns.

The novel I chose to concentrate on in my Thayer entry for 1001 Midnights was Out, Brief Candle!, which like Christie’s Death in the Air (1935) is about a murder on an airliner in flight.

It’s twice as long as it need have been, but the solution is passably clever, and I considered this the best Thayer I had read up to the time I wrote the entry. Later I discovered a copy of Evil Root (1949), which brings Clancy to a luxurious retirement home with stiff and unrefundable entrance fees and a suspiciously high death rate among recent residents. This was mystery writer/critic Jon L. Breen’s favorite Thayer, and after I’d read it I found I had to agree with him.

The Second Bullet (1934) has always had a special cachet for me because it’s set in the mountains of northern New Jersey, the state where I grew up. Thayer sets the scene as only she can: “[T]he strong autumn sun warmed the hollows with mists of purple and gold. The color of the woods sang like a great organ. The sky was that thrilling cobalt that seems as if it must be fragrant. Great clouds piled into the zenith. The air was warm and full-flavored like … claret properly unchilled.â€

An auto mishap brings Clancy and Wiggar to the remote mansion of a famous “psychic-analyst†where they discover that he seems to have shot himself to death shortly before their arrival. Concluding that the local cops are idiots who know nothing about detective work and speak in Texas cracker accents to boot (“Meet Captain Tom Joyce, inspector for this here countyâ€), Clancy decides to conceal crucial evidence, invite himself and Wiggar as house guests and stay on to investigate what he has quickly concluded is murder.

In due course he exposes yet another off-the-wall crime method. The murderer and an accomplice drove up to the victim’s isolated house in a utility truck with a long ladder. When the ladder was aligned with the victim’s second-story window, the killer climbed it and, like a demented Paladin, challenged the guy inside to a gun duel!

After twenty years as a northern Californian and resident of Berkeley, Thayer moved to the southern tip of the state and was living with relatives in Coronado in the fall of 1970 when she was interviewed by Jon Breen. At 96, Jon reported, she was still in relatively decent health and able to read with the aid of a combination lamp and magnifying glass.

She was extremely modest about her many mystery novels, saying only that “some are worse than others.†A year or so later there was an exhibition of some of her artwork at the UCLA library. She died on November 18, 1973, just a few months short of her 100th birthday.

The First Violin, by Jessie Fothergill, 1896. Cover design attributed to Lee Thayer.

February 8th, 2011 at 10:53 pm

I’m working on my review of Lee Thayer right now, so I want to save some comments for that. But, while she sounds a lot like Carolyn Wells in this review (i.e., bloomin’ daft), the book I read was better than most all Carolyn Wells.

Though it was still not very good.

I notice the comment attributed to Ira Levin concerning John Rhode. While some Rhode, especially in the 1950s, can be quite dull, at his best he’s miles above writers like Carolyn Wells and Lee Thayer, at least based on my reading of these ladies. The same would go for Freeman Wills Crofts or J. J. Connington or R. Austin Freeman. These writers were all technically superb plotters and better understood math, science and technology.

By the way, “dark as the inside of a cow” used to be an expression in both the U.S. and U.K. Though I suppose she would have been better served having a character say it.

February 8th, 2011 at 10:54 pm

The only thing is we may be making Thayer sound more interesting as a writer than she ever really was.

My memories (and it has been thrirty years since I read one of her books) was that she did not actually induce sleep, but contributed to a desire for it, though not in the same pleasant way as warm milk and cookies.

That said, thanks for all the biographical info and the look at some of the books. They mostly confirm what I thought of them, though admittedly one or two sound better than any of the one’s I read.

You have to respect a detective and writer who calls on God to handle the messy details of justice and retribution — even Melville Davidson Post’s Uncle Abner couldn’t actually conjure up Divine Retribution however much he referenced it.

“Dark as the inside of a cow.” And Chandler thought he was the genre’s master of similie and metaphor.

February 8th, 2011 at 11:06 pm

Curt

I don’t think you can (or that you meant to in a critical sense) seriously compare Thayer with Crofts, Connington, and Freeman. Where they are deliberate she is plodding; where they are dry she is barren; and where they are carefully constructed she is reckless. Their thrills may be intellectual, but they are thrills.

Thayer is the type writer, who when she does manage a few decent lines or comes up with a decent plot element the greatest praise you feel like bestowing on her is, “well, that wasn’t as stupid as usual.”

Re Carolyn Wells, one of two of her books benefit from a faint sheen of nostalia when read today; a patina of old wood stain, velvet, sepia tones, and chantilly lace. Thayer is a bit too contemporary for that, so doesn’t have the charm (for me). She is probably better than Wells technically, but overall offers even less rewards.

Wells is certainly likely to induce groans, but Thayer is more likely to induce snoring.

February 9th, 2011 at 12:14 am

David, very well stated!

I just sent my Thayer take to Steve. I can’t say it’s too different from the opinions expressed here. It definitely has semi-“alternative classic” aspects, even though it’s not as insane as the best (i.e., the worst) Wells.

February 9th, 2011 at 1:01 am

Thayer’s two greatest feats of talent in the field may well be that Lee Thayer is a good name for a mystery writer; short, memorable, and Anglo-Saxon (could be a man or a woman, English or American); and Peter Clancy and Wiggar are excellent names for a sleuth and his butler.

Sadly she seems to have spent what little ability she had on her pseudonym and the name of her sleuth and his assistant.

Curt

Looking forward to your review.

February 9th, 2011 at 8:32 am

Lee Thayer also was published in the pulps. Here are two serials and two complete novels:

Detective Story-Aug 1,1925-Sep 5,1925. Six part serial THE SNAKE IN THE GRASS.

Detective Story-Jul 10,1926-Aug 14,1926. Six part serial THAT WHICH I FEARED.

Detective Classics-June 1931. Complete novel, DEAD MAN’S SHOES.

Detective Classics-July 1931. Complete novel, THEY TELL NO TALES.

February 9th, 2011 at 11:19 am

I feel as if I was responsible for opening this Pandora’s Box.

But wait… What’s that in the corner of the trunk? A shining jewel? Could it be…?

No, it’s just the silver paper from a Hershey bar glinting feebly in this dim light. So much for Hope.

February 9th, 2011 at 12:01 pm

David

As far as her feats in the field are concerned, I think you could add the covers of the dust jackets she designed. I don’t much care for the one with the parrot on the skeleton’s hand (wrapped around to the spine and not seen) but to my eye the others are very nice combinations of artwork and expressive lettering.

Walker

Thanks for the list of her pulp appearances. When I first saw the comment you left, though, I was hoping you might have come up with a short story she did, but apparently she never did any.

The only book of hers that was came out in paperback in the US was MURDER IS OUT, which was published as Bart House Mystery #16 in 1945. (If I’m wrong about this, please let me know.)

John

You’re right. You did start all this, back with your review of THE MYSTERY OF THE 13th FLOOR on your blog:

http://prettysinister.blogspot.com/2011/02/mystery-of-13th-floor-1919-lee-thayer.html

I’m not sure why both Lee Thayer and Carolyn Wells, two women with such similar careers, have produced so many comments when their books have been discussed, but they have. Probably because they each wrote so many books and so many readers of this blog have sampled at least one of them — and haven’t forgotten the experience, either!

Coming up next: Curt’s review of The Scrimshaw Millions.

— Steve

February 9th, 2011 at 2:50 pm

How can you resist a serial titled “That Which I Feared”? What?! What?!

February 9th, 2011 at 2:53 pm

Oh, and by the way, I think some of Thayer’s jackets are quite good, like The Scrimshaw Millions (I’m just sorry my copy of it is so poor). And the hardcover binding decoration is excellent as well.

February 9th, 2011 at 6:28 pm

Were we remembering Thayer as a book designer and dust jacket artist I would be full of praise for her. As a novelist, sadly not so much.

I feel in this case like Alice Roosevelt — if you don’t have anything nice to say — sit by me.

February 9th, 2011 at 8:41 pm

I suppose it’s kind of like “she makes her own clothes,” though of course from a collector’s standpoint the attractive jackets have appeal (Carolyn Wells books often are quite attractive as well, and well-made).

I have Ransom Racket (with jacket), by the way, but now Mr. Nevins has gone and spoiled it for me! 😉

February 9th, 2011 at 9:34 pm

Curt

Re your comment #9, neither of the pulp serials Walker cited in comment #6 were published under those titles in hardcover:

Detective Story-Aug 1,1925-Sep 5,1925. Six part serial THE SNAKE IN THE GRASS.

Detective Story-Jul 10,1926-Aug 14,1926. Six part serial THAT WHICH I FEARED.

I am assuming that titles were changed by somebody somewhere along the way, and that there are not two Lee Thayer mysteries we didn’t know about before.

— Steve

February 9th, 2011 at 9:59 pm

I need to know what book that is because I simply must find out what that which she (he?) feared was!

February 9th, 2011 at 11:34 pm

THAT WHICH SHE FEARED, might well prove to be these reviews.

February 10th, 2011 at 12:55 am

Though I fear to read a Lee Thayer novel I bravely looked in my copies of DETECTIVE STORY containing the serial THAT WHICH I FEARED.

As usual with Thayer, the detective is Peter Clancy who in this story is in disguise as Doctor Charles Ely. A blurb for the serial states:

“It was only an evil dream of someone being murdered that compelled Kirby Lane to rush to the “Heywood House” in the early morning. But he faced grim reality when he found his dream had come true.”

So it looks like the so called “fear” was the dream that Warren Heywood was dead. Turned out to be true and at this point my own fear overcame me and I stopped reading.

February 10th, 2011 at 1:12 pm

News Flash — “That Which I Feared” became ALIAS DR ELY.

I know that because I recently bought this book from a seller on eBay for $4! Poor Lee, people are practically giving her books away.

David –

I will admit your last two posts made me crack up. Dishy old devil that you are.

And thanks for stopping by the Pretty Sinister Books blog.