|

PLAYING WITH

FIRE:

DAN J. MARLOWE, AL NUSSBAUM AND EARL DRAKE by Josef Hoffmann There’s

no giving up, and no breathing space,

no vacillation in thought, courage or mood. The fire arts, with aspect most dramatic, force the battle between man and form. The most important active agent, FIRE, is also the greatest enemy. - Paul Valéry, Pieces sur l’art One night a woman falls ill and, within a few days, dies. With her, her husband loses everything that had bound him to his middle class way of life. He gives up his job as a senior clerk in a tobacco wholesale company, sells his house and leaves Washington D.C. He could take up his former profession again. Not that of a bookkeeper or an insurance salesman, but of a professional gambler. However the man, aged 43, makes a very different decision. He moves to New York City, finds a room in a small hotel, and begins to write. Dan James Marlowe is on his way to becoming a free-lance writer.  Marlowe had always loved

stories. He gives a

lot of thought to the stories he himself now wants to tell, making

drafts of scenes, dialogues and characters. Then he begins to

write. He even attends writing courses in the nearby YMCA.

One day, literary agent James Reach comes to give a talk to the

class. Dan Marlowe attracts his attention. The two become

friends. Reach sends Marlowe’s first manuscript to various

publishers. In the meantime, Marlowe, is already writing a

sequel. He has nothing else to do. Both novels, Doorway to Death and Killer with a Key are published by

Avon in 1959, just two years after Marlowe had decided to devote

himself to writing. Marlowe had always loved

stories. He gives a

lot of thought to the stories he himself now wants to tell, making

drafts of scenes, dialogues and characters. Then he begins to

write. He even attends writing courses in the nearby YMCA.

One day, literary agent James Reach comes to give a talk to the

class. Dan Marlowe attracts his attention. The two become

friends. Reach sends Marlowe’s first manuscript to various

publishers. In the meantime, Marlowe, is already writing a

sequel. He has nothing else to do. Both novels, Doorway to Death and Killer with a Key are published by

Avon in 1959, just two years after Marlowe had decided to devote

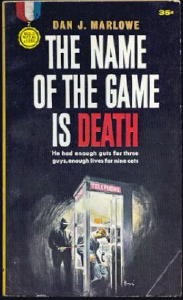

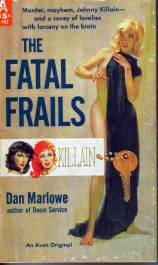

himself to writing.Whereas most writers produce for years in vain before having a work published, Marlowe is successful in his new life right from the start. Before the very eyes of his reading public he acquires and perfects his craft. His story-telling proceeds according to a strict and professional calculation. His novels are constructed on the foundation stone of a detailed draft of at least 5000 words. He also writes newspaper articles and short stories for “girlie magazines.” Marlowe writes daily, often working on one or more projects at a time. What is important to him is not so much what he is writing, as that he is writing. And that he can earn a living from it. He sees himself not as an artist but as a story teller. He is driven by a presumptuous, almost heroic will to compete with television. His stories were to be so gripping that the readers would not be interested in turning on the television. The power of his narrative and his language were to bind them totally to the book (as Poe once postulated). With some of his texts Marlowe actually achieved this aim. Not included among these texts, however, are his first five novels, featuring the hero Johnny Killain. Killain works as a night porter, bouncer and part-time detective in a hotel. In many points this hotel is similar to Marlowe’s own New York abode. Killain is a character very typical of the “hard-boiled detective story”: of massive physique, aggressive, cool, reckless, a survivor. He is bubbling with sarcastic wit and, of course, is a great man for the women. Although the Killain novels contain some of the qualities of the “Black Mask school” of the 20s and 30s, today they seem in parts to be full of clichés and straining after effect. For Marlowe, they provide a good basis for his later writing. Then comes Backfire (1961), a turning point leading in the direction of his best novels. It tells the story of a policeman caught up in a tragic love affair, and touches on much darker emotional realms than the fast-moving Killain stories: it is reminiscent of Simenon, Goodis and Whittington.  1962 sees the

appearance

of Marlowe’s “masterpiece”

– in the opinion of George Kelley, Bill Pronzini, Marcia Muller

and other experts. With this book Dan Marlowe takes his place

among the great American crime writers. It is called The Name of the Game Is Death.

In a review for the New York Times, Anthony Boucher writes: “This is

the story of a completely callous and amoral criminal..., told in his

own self-justified and casual terms, tensely plotted, forcefully

written, and extraordinarily effective in its presentation of a

viewpoint quite outside humanity’s expected patterns.” 1962 sees the

appearance

of Marlowe’s “masterpiece”

– in the opinion of George Kelley, Bill Pronzini, Marcia Muller

and other experts. With this book Dan Marlowe takes his place

among the great American crime writers. It is called The Name of the Game Is Death.

In a review for the New York Times, Anthony Boucher writes: “This is

the story of a completely callous and amoral criminal..., told in his

own self-justified and casual terms, tensely plotted, forcefully

written, and extraordinarily effective in its presentation of a

viewpoint quite outside humanity’s expected patterns.”The book is about a bank robber and murderer. In his bourgeois life he calls himself Roy Martin, or Chet Arnold, and by profession is a “tree surgeon.” The story is told from the point of view of the anti-hero, Marlowe’s preferred narrative perspective from now on. The action is strewn with memories of fundamental and often violent experiences from his childhood and youth. A feeling of identification with the “I”, the criminal narrator, is awakened. The process by which the novel’s hero finally breaks with society is described on the back cover of the Gold Medal paperback in a modified extract: On the day they sentenced Olly Barnes to

fifteen years, I quit the human race. I never went back to my job

and I’ve never done a legitimate day’s work since.

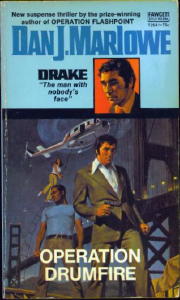

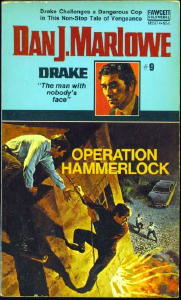

I bought a gun in a hockshop and was surprised to learn how easy it is to knock off gas stations. The money piled up and I bought a second-hand car and drove the 180 miles back across the state. Back to Winick, the guy who railroaded Olly Barnes. I rang his doorbell one night and shot him in the face, four times. He went backward in a kind of shambling trot. “That’s for Olly”, I told him. But he didn’t hear me. He was dead before he hit the floor. Winick was the first. He wasn’t the last. The story begins at a later stage in the gangster-hero’s career. After a bank raid “Chet Arnold,” alias “Roy Martin” and his partner Bunny split up. Chet Arnold goes into hiding in Phoenix, Arizona. He has a gun shot wound which needs time to heal. Bunny travels to Hudson, Florida, taking with him the largest part of the booty. When the envelopes full of money sent to be called for by one “Roy Martin” suddenly stop arriving, the gangster goes in search of Bunny and the money. This transition from the role of criminal on the run to that of bloodhound seeking revenge marks an effective turn in the plot. It allows the author to weave elements of the detective story into his gangster story, the latter thriving more typically on action and violence. The double life of the hero as gangster and “tree surgeon” also facilitates abrupt changes of milieu and perspective. This short novel, extremely dense both in action and incident, holds the reader spellbound, like the ritual of a bull-fight. It describes a pitiless and professional game of life and death, as promised in the title. The front cover of the Gold Medal original edition advertises with the comment: “He had enough guts for three guys, enough lives for nine cats”. How true! The passionately a-social, nameless, and, at the end, faceless criminal does have “guts.” Without the slightest hesitation he risks death, rushing headlong into fire. The book’s hero has no clearly defined identity, no real name. These he was to receive from his author only many years later with the help of one Al Nussbaum. At that time Al Nussbaum was serving a 40-year prison sentence for bank robbery. While writing The Name of the Game Is Death, Marlowe, who was an avid reader, presumably was inspired not only by relevant books such as Jim Thompson’s The Getaway, but also by newspaper reports on crimes. Perhaps he read about the spectacular bank robberies of Al Nussbaum and Bobby Wilcoxson, committed in 1960 and 1961. During a raid which took place on 15.12.1961, Wilcoxson shot a watchman in the Lafayette National Bank, Brooklyn N.Y., and wounded a policeman. Nussbaum and Wilcoxson were on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted List.” J. Edgar Hoover described the 32 year old Wilcoxson as “the most wanted man since Dillinger” and the 27 year old Nussbaum as “the most cunning fugitive in the country.” They were caught in 1962. Wilcoxson was sentenced to life in prison, Nussbaum to 40 years, not least because he kept so consistently silent. Dan Marlowe’s documentary, “Anatomy of a Crime Wave,” which he wrote together with Albert Nussbaum in 1964, begins with the question: How does one manage to gain “honorary titles” such as those conferred by J. Edgar Hoover? Our question is: How did Marlowe and Nussbaum ever manage to get together? On the run from the FBI, Nussbaum had spent some time in hiding. He scarcely left his flat and, as an attempt at camouflage, even claimed to be a writer. During this time he got to know the daily routine of a writer. Nussbaum did not write, but he did read a lot; among other things, The Name of the Game is Death. He was so impressed by the book that he got in touch with the author through the publishers. After his arrest he wrote to Marlowe from jail. Marlowe then visited Nussbaum, got to know him, and wrote about him. This resulted in a life-long friendship.  Their first joint production, “Anatomy of a Crime Wave,” was intended for publication in the mass circulation magazine, The Saturday Evening Post. Publication was stopped, however, as a result of objections made by the FBI to the editors. Apparantly the FBI was afraid that the documentary about the bank robber, written as it was with such exactitude and verve, could lead to imitations or to the creation of a legend. The story presents Wilcoxson as an extremely tough guy, and Nussbaum as a highly intelligent technician and planner. Together they make up a criminal “super-team”: “Separately, neither man had shown a particularly dangerous potential in previous skirmishes against society; together, after meeting in federal prison at Chillicothe, Ohio, they fused like nitric acid and glycerine to form an equally explosive compound.” (“Anatomy of a Crime Wave,” page 1, manuscript) It was almost as if in Marlowe’s literary imagination this explosive mixture had found a form and a name – Earl Drake, alias Chet Arnold. The figure has some of the author’s own features; his age, his knowledgeable passion for horse-racing, betting and gambling, and his great love of animals. The name Earl Drake was Al Nussbaum’s invention. Earl is borrowed from Roy Earle, the gangster in W. Burnett’s “High Sierra,” played in the film by Humphrey Bogart. Drake was a reminder of Sir Francis Drake, the sea-farer, explorer and pirate - quite a name for the lawless hero of a series of novels. For years, friends of Marlowe’s, among them Nussbaum, tried to persuade him to write a sequel to his highly renowned The Name of the Game Is Death. Marlowe was not quite sure how this was supposed to work. The story had been conceived as a separate and complete book. The main figure had received burns from head to toe. Thus, he could only re-appear as an invalid, or someone in need of permanent care. Nussbaum suggested to Marlowe that he go through the novel for him, looking out for the elements which constituted the figure of the hero, and for ways in which the story might be continued. Nussbaum then produced an outline of the character for the series, gave him a name, and drew up a 60-page concept for the sequel. In three weeks flat Marlowe wrote the second volume of the Earl Drake series. It appeared in 1969 published by Gold Medal under the title One Endless Hour. Earl Drake, the god-like phoenix, is burned in a fire and then born again. But Drake is not conceived as a mythical being. He is still a vulnerable human being. The miracle performed by an ingenious cosmetic surgeon on Earl Drake’s skin cannot be repeated. Drake may not go through fire ever again. Yet somehow he keeps coming into close contact with fire: exploding petrol tanks, Molotow cocktails, burning buildings all threaten him with fatal burns. The pattern of tension in the Earl Drake stories functions as the reverse of the German saying: “a burnt child dreads fire.” The creator of Earl Drake does not dread fire. On the contrary, his crime fiction is almost pyromaniacal. Only very few of his novels and short stories have no decisive fires and explosions. Marlowe is all too capable of kindling fires, causing flames to flicker, conjuring up an inferno. In the subsequent ten Earl Drake volumes, fire is announced in the very titles: Operation Fireball, Operation Drumfire and Flashpoint, for which Marlowe received the Edgar Allan Poe Award for the best “paperback original” for the year 1970. As so often with literary prizes, this Edgar was awarded for a book which is in no way the most successful work of this revered author. Marlowe’s best creative period was already behind him. This period is symbolically flanked by the first and second volumes of the Drake series, dating from 1962 and 1969. Also from this period are his best non-Drake novels, Strongarm (1963), Never Live Twice (1964), Four for the Money (1966), The Vengeance Man (1966), and one of his best short stories, “All the Way Home” (1965). The latter was later included by Arthur Maling in the anthology When Last Seen. In this story Marlowe distances himself somewhat from typical crime fiction, but both in theme and symbolism he remains close to fire. Fire, according to psychoanalytical studies of crime fiction, often glimmers unnoticed and can flare up dangerously at some point in a person’s life: it is the lust of uncontrolled drives, dammed up and held back by taboos, but never quite extinguished.  From 1969 onwards, and

with the exception of some

short stories, newspaper articles and high-low-books, Marlowe wrote

Earl Drake novels almost exclusively. At the recommendation of

Fawcett, his publisher, however, he allows the hero to undergo a

change. The professional criminal becomes a sometime undercover

CIA agent. Each book is given the password “Operation,” even new

editions of old Earl Drake novels. From 1969 onwards, and

with the exception of some

short stories, newspaper articles and high-low-books, Marlowe wrote

Earl Drake novels almost exclusively. At the recommendation of

Fawcett, his publisher, however, he allows the hero to undergo a

change. The professional criminal becomes a sometime undercover

CIA agent. Each book is given the password “Operation,” even new

editions of old Earl Drake novels. The reason? Commercial considerations. Since 1967, Fawcett Gold Medal had been publishing the gangster series “Parker,” by Richard Stark (Donald Westlake), the first volume of which was published in 1962, the same year as The Name of the Game Is Death. It was assumed at Fawcett that the market could only take one gangster series, and as Stark’s novels were more established, they were given priority over the Earl Drake series. In view of the sales successes of spy and political thrillers à la James Bond, the Earl Drake series was also to be pointed in this direction (with the exception of Operation Whiplash in which the setting and action of the first two Drake stories are taken up again). The last novel in the series, Operation Counterpunch, appeared in 1976, a year which changed Marlowe’s life completely. He suffered a minor stroke which damaged his memory. He no longer knew who he was, where he lived, what he had done before, etc. All of his personal memory was gone. His writing and language abilities, however, were still intact. Thus he found himself in a situation similar to one he had described some years earlier in Never Live Twice. After Marlowe had recovered somewhat, one of the first things he did was to look for a job. Fortunately, an acquaintance of his visited him and was able to tell him who he was, etc. Marlowe remained in California for health reasons, but in order to reconstruct his former life fully he had to gather information. He was helped in this by his friend, Al Nussbaum. Nussbaum had been released from jail shortly before Marlowe’s stroke. They had kept up their correspondence for more than ten years, writing one or two letters a week. In the mid 60s Nussbaum had himself begun to write and Marlowe supported him fully in his literary efforts. The remarks he added in the margins of Nussbaum’s short story manuscripts are often enough to fill just as many more pages of typescript. Marlowe helped him to get the stories to publishers. In return, Nussbaum provided him with advice, above all technical information, based on his expert knowledge of weapons, safe locks, alarm installations etc., not to mention his experience in the detailed planning and realisation of crimes, and other insider knowledge. Sometimes Marlowe’s descriptions were so exact that he had to leave out some essential detail so as not to be accused of providing instruction manuals for criminal acts. Marlowe and Nussbaum both wrote under various pseudonyms, sometimes they even use the same ones: Jaime Sandaval and Albert Avellano. Avellano is Spanish for hazelnut tree, Nussbaum means nut tree in German, and Albert is Nussbaum’s first name. The friendship between the famous crime fiction writer, who as a result of his public status was elected mayor pro tem of the small town of Harbor Beach, Michigan, and the jailed weapons dealer and bank robber Nussbaum, becomes manifest in Marlowe’s texts in the number 81332. This number turns up again and again, either as a car or plane registration, or as part of an address, etc. It is Nussbaum’s prisoner’s number, which Marlowe, as his friend, used as an “inside” joke. Because Marlowe was in need of help due to his amnesia, Nussbaum put himself at his disposal. His main task was to provide Marlowe with the information he needed about his person, his past, and his relations to other people. Marlowe was still able to write in his accustomed style but he no longer knew what he had already written so there was a danger he might repeat himself. Nussbaum, who knew Marlowe’s texts better than anyone else, helped him.  Although he did not write any more crime novels, he did continue to write non-stop. He published short stories in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, in other mystery magazines, and in anthologies and other magazines. He also wrote spy stories and sports stories for youth publications, plus articles and reviews for newspapers. As a secondary source of income Marlowe continued to bet on race horses, and as he was always a very clever gambler, managed as a rule to win more than he lost. All his life Marlowe was an able business man. Like many of his colleagues he handled his ideas and texts economically, sometimes extracting and re-using parts of them. He was also driven by a wish to improve his stories, make them more effective. “By Means Unlovely” is probably Marlowe’s last work. It centers around a chapter from the Killain novel Killer with a Key (1959), which he adapts slightly, giving it a successful new ending. This short story appeared in 1987 – one year after Marlowe’s death – in the anthology Murder, California Style, put out by the Southern California Chapter of the Mystery Writers of America. This highly representative collection is dedicated to, among others, Dan J. Marlowe. “Nobody wrote tougher prose than Dan J. Marlowe. Nobody,” according to Barry Gifford. In his legendary Black Lizard series Barry Gifford made The Name of the Game Is Death and three other Marlowe novels available to the American public of the 80s, thus also re-discovering him for many former readers. Although Marlowe’s books have been out of print for several years now, the reputation of his gangster-hero remains unbroken among fans of hard-boiled crime stories. With Earl Drake, alias Chet Arnold, Marlowe created one of the most unmistakable figures in American crime fiction. The very name Drake resounds with associations: the fire spitting dragon, the proverbially harsh lawgiver Draco, the aristocratic and the archaic. Drake lives according to his own laws, ignoring the rule of law, morals or social conventions. “You’re amoral”, the prison psychiatrist told him. “You have no respect for authority. Y our values are not civilized values.” Earl Drake does not contradict him. To his lover Hazel he explains his behaviour by means of a comparison: “Years ago I saw a cartoon in a magazine. A slick-looking battalion is marching along in perfect cadence except for one raggedy-assed, stumble-footed guy out of step with a rock-faced sergeant alongside him giving him hell. The tag line underneath has the out-of-step character telling the sergeant he hears a different drum. The inference being that he can’t help it if the rest of them are out of step. That’s me. I march to a different band.” The image of a different rhythm, a different beat, also applies to the rebellious, radical attitude to life of the youth and pop culture of the 60s. The spoken language and rhythm of the first two Drake novels are reminiscent of the pop, fast-moving style of the films and music of those years. So too are the somewhat bizarre plots which at times remind us of the films of John Waters. John Waters, by the way, counted James M. Cain and Jim Thompson among his favourite authors as Marlowe did. But the heros and heroines of Thompson, Goodis, Whittington and many others of the hard-boiled paperback original writers all have their roots more in the 40s and 50s. Earl Drake on the other hand is a product of the 60s. His unyielding attitude, his toughness and insubordination are coupled with a fine sensitivity, wit and fantasy. In the pursuit of his desires Drake is as a-social, insistent and merciless as the unconscious itself. But in his case “id” is always in harmony with a biting intelligence, with technical expertise, cool, callousness and even discipline. To put it in Freudian terms: Drake embodies an optimal combination of “id” and “ego”, with the “super-ego” coming to grief. This too is a myth of the 60s: the release of suppressed energies through the elimination of the repressive super-ego. Although displaying this type of local color, Marlowe’s narrative and linguistic style still have their appeal today thanks to his laconic and non-compromising attitude. His tones still grate on our ears or hit us in the gut. The shock that Marlowe creates has nothing to do with the horror perpetrated by series killers who leave bloody heaps of human limbs strewn along their path. The gangster Earl Drake is not a psychopath. He is a clear thinking, realistic and sensitive individualist who nevertheless uses violence as if it were self evident, i.e. professionally, like a gambler his chips, in short, with a certain indifferent superiority. In Marlowe, violence and crime simply seem normal. The toughness of his crime stories stems from the core of his narrative and descriptive style. They are impressive presentations of the shadier side of the “pursuit of happiness” as anchored in the American Bill of Rights. In conclusion I would like to thank the late Al Nussbaum, who was generous enough to provide me with a lot of very interesting material for this essay. Whoever takes a look through back issues of Hitchcock magazines and anthologies has a good chance of finding some of Nussbaum’s more than one hundred published short stories, either under his own name or one of his many pseudonyms (Carl Martin, Albert Avellano, A. F. Oreshnik, Alberto N. Martin, etc.). His last story to date appeared in the September 1992 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, with a brief introduction to the author contained in one of the footnotes. This article first appeared in slightly

different form in the Australian crime magazine Mean Streets, 10 December 1993.

Copyright © 1993, 2006 by Dr. Josef Hoffman. BIBLIOGRAPHY: DAN J(ames) MARLOWE,

1914-1986.

Adapted from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. Doorway to Death. Avon T-307, pbo, 1959. [Johnny Killain]  Killer with a Key. Avon T-349, pbo, 1959. [Johnny Killain] Doom Service. Avon T-392, pbo, 1960. [Johnny Killain] The Fatal Frails. Avon T-452, pbo, 1960. [Johnny Killain] Shake a Crooked Town. Avon T-491, pbo, 1961. [Johnny Killain] Backfire. Berkley G575, pbo, November 1961. The Name of the Game Is Death. Gold Medal s1184, pbo, January 1962. [Earl Drake] Fawcett Gold Medal T2663, pb, revised edition, January 1973. Black Lizard Books/Creative Arts, pb, April 1988. Vintage, pb, April 1993. Strongarm. Gold Medal k1340, pbo, September 1963. Black Lizard Books/Creative Arts, pb, December 1988. Never Live Twice. Gold Medal k1441, pbo, 1964. Black Lizard Books/Creative Arts, pb, April 1988. Death Deep Down. Gold Medal k1524, pbo, 1965. [McGinnis cover]  Four for the Money. Gold Medal d1734, pbo, 1966. The Vengeance Man. Gold Medal d1645, pbo, 1966. Black Lizard Books/Creative Arts, pb, November 1988. Route of the Red Gold. Gold Medal d1791, pbo, 1967. [McGinnis cover] The Raven Is a Blood Red Bird [with William C. Odell]. Gold Medal d1874, pbo, 1967. One Endless Hour. Gold Medal, pbo, 1969. [Earl Drake] Fawcett Gold Medal T2662; 2nd pr., January 1973. Operation Fireball. Gold Medal R2141, pbo, 1969. [Earl Drake; McGinnis cover] Fawcett Gold Medal R2567, pb, May 1972. Flashpoint. Gold Medal R2283, pbo, August 1970. [Earl Drake; McGinnis cover] = Reprinted as Operation Flashpoint, Gold Medal T2446, pb, 1972. Fawcett Gold Medal M2934, pb, as Operation Flashpoint, – . Operation Breakthrough. Gold Medal T2486, pbo, October 1971. [Earl Drake] Operation Checkmate. Fawcett Gold Medal T26231, pbo, October 1972 [Earl Drake]  Operation Drumfire. Fawcett Gold Medal T2541, pbo, April 1972. [Earl Drake] Operation Stranglehold. Fawcett Gold Medal T2723, pbo, May 1973. [Earl Drake] Operation Whiplash. Fawcett Gold Medal T2866, pbo, October 1973. [Earl Drake] Operation Hammerlock. Fawcett Gold Medal M2974, pbo, June 1974. [Earl Drake] Operation Deathmaker. Fawcett Gold Medal M3175, pbo, January 1975. [Earl Drake] Operation Counterpunch. Fawcett Gold Medal, pbo, February 1976. [Earl Drake] - As by GAR WILSON [house name] Guerrilla Games. Gold Eagle, pbo, June 1982. [Phoenix Force #2] ADULT FICTION: In a previous short article, researcher Bart Choveric points out the evidence that strongly suggests that Marlowe wrote several works of erotic fiction in 1971 under various pen names. CHILDREN’S FICTION - Not included at the present time. SHORT FICTION - Not included at the present time. Is there a Gold Medal Pantheon? Probably not, but if one existed, I’d put Dan J. Marlowe in it. Marlowe, as far as I’m concerned, wrote one of the best GM novels ever, The Name of the Game is Death. The book has such a great opening scene that you wonder if the rest of the book can live up to it, but it does, and the ending even tops the beginning. When it comes to paperback originals, this book is one of the classics. The plot has to do with a man named Earl Drake, a professional bank robber and cold-blooded killer. He likes animals, which is nice, but he doesn’t have anything resembling a conscience. Marlowe doesn’t spare him, or the reader, and the book’s narrative drive is tremendous. This is a read-in-one-sitting novel if there ever was one. And it’s one that you might want to read again as soon as you finish it the first time. I know I did. Drake returns in One Endless Hour, which isn’t quite as exciting as The Name of the Game. But then few books are. It’s still well worth your time, as Drake escapes from a mental institution and gets ready to rob another bank. Drake seems to be a little bit softer in this one. Maybe the events of The Name of the Game had something to do with that. A softer Drake, however, is still about three times as tough as your average crook. Another don’t-miss Gold Medal.  Unfortunately, someone at GM got the idea that Earl Drake would make a great series character, working undercover for the U.S. Government, and he was pressed into service in a number of books, all with “Operation” in the title. You don’t have to worry about finding these, though they’re entertaining in their own way. They just don’t represent the best of Marlowe’s work or the best of Gold Medal, but I’m betting they paid Marlowe’s bills and left him with a little spending money. And while you’re reading Marlowe, don’t forget that he wrote several other terrific GM originals. One of the best, and another classic, is The Vengeance Man, which comes about as close to equaling such Jim Thompson works as The Killer Inside Me and Pop. 1280 as any book possibly could. The psycho who narrates is just as chilling as Thompson’s Lou Ford, and I once asked Marlowe if in writing The Vengeance Man he’d been influenced by Thompson’s books. He said that he had, and it shows. Yet another one not to miss is Strongarm. I happen to object to the prologue in this one, and I wonder if GM’s editors didn’t ask Marlowe to add it. I think readers could figure things out for themselves without it, and it gets in the way of another eye-popping opening chapter. The main character is called Pete Karma, which isn’t his real name, and I’ve often wondered if Marlowe didn’t intend for Karma to be the series character that Earl Drake became. Too bad I never asked him. And then there’s Four for the Money, a stand-alone bank robbery novel that’s just a tiny notch below the other Marlowe books I’ve already mentioned. It has all of Marlowe’s virtuesterse narrative, brisk pacing, tight plotting, and interesting characters. You can’t go wrong with this one, either. Word of Warning: One book you should probably avoid is the revised edition of The Name of the Game is Death. I’ve never read it, but GM had it rewritten at least slightly to make Drake more acceptable as a series hero. My advice would be to stick with the original. Non-Gold Medal Bonus: Before he broke into the Gold Medal fold, Marlowe wrote a series of five books for Avon. These all featured a guy named Johnny Killian, Bell Captain at the Hotel Duarte. You could call the Killian novels apprentice work, but Marlowe knew what he was doing from the start. Don’t pass any of these up if they come your way. This column first appeared in Mystery*File 46, November 2004.

YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Unless otherwise specified, copyright © 2004, 2006 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors. |