|

MURDER

MYSTERY MONTHLIES: The Early Crime Digests, by Peter Enfantino

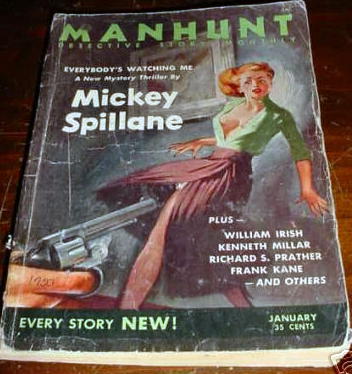

Hard boiled magazine crime fiction began evolving into a much more serious form after WW II. Gone were all the gimmick stories about blind detectives and Sherlockian gumshoes and super-hero-like crime busters (the Phantom, etc.) In was the same realism found in Hammett, etc. No other magazine reflected this change better than Manhunt – best writers, best design, best circulation numbers. Despite the fact that it was basically a story dump for the clients of Scott Meredith, its contribution to crime fiction can still be felt today. -Ed Gorman Manhunt was not only the first of the hardboiled crime digests, but the best during the period 1953-1958, before it began to decline in quality. Main reason was the range of writers they published. Not only front-rank crime writers such as James M. Cain, Rex Stout, Fredric Brown, Mickey Spillane, Erle Stanley Gardner, John D. MacDonald, and Ross Macdonald, and newcomers who would eventually join the front rank such as Evan Hunter, but a surprising array of literary figures of the day – Nelson Algren, Erskine Caldwell, James T. Farrell, Charles Jackson, and Ira Levin. No other magazine except EQMM even came close to publishing good stories by that many major names. -Bill Pronzini I’ve been collecting crime digests for over a decade now, and the question I get asked the most is: “So is Manhunt the best crime digest of all time?” Funny you should ask. For the last three years, I’ve been working on an annotated index to Manhunt, so obviously I have something of a fondness for the title. But is it the best? Well, first of all, I haven’t read every single issue of every single crime digest ever published. All I can comment on is the material I’ve read and, so far, it’s pretty damn good. Other titles give it a run: a lot of first-rate stories appeared in Ellery Queen in the 1940s and 1950s, Alfred Hitchcock and Mike Shayne in the 1960s, and the various short-lived digests of the 1950s (Justice, Web Detective, Ed McBain, etc.), but Manhunt wins out for the same reason the New York Yankees usually dominated: they had all the heavy hitters. Mickey Spillane, John D. MacDonald, David Goodis, Harry Whittington, Gil Brewer, Jonathon Craig, Jack Ritchie, Hal Ellson, Fletcher Flora, Craig Rice, Ed McBain (who, along with his good friends Evan Hunter, Richard Marsten and Hunt Collins, saw 45 stories published in Manhunt), and many others. A veritable who’s who of “hard crime” in the 1950s. Manhunt was first published by Flying Eagle Publications in January 1953. Having a publisher who was willing to pay the best rates undoubtedly helped editor John McCloud lure these authors away from their well paying “day jobs” at Gold Medal for a little moonlighting. Obviously the plan paid off, since editor McCloud reported in the second issue that the premiere had all but sold out and readers were clamoring for more copies. The magazine continued publishing for 14 years and 114 issues, with a few hiccups along the way: in 1957, in an experiment to increase circulation, Flying Eagle changed the format of Manhunt from digest to “bedsheet” (full magazine sized) so that the title would not be placed behind larger magazines (and therefore lost to the consumer). The experiment was a failure and, after 12 issues, the digest format returned, albeit on a bi-monthly schedule. Unfortunately, the damage had been done, and the top writers headed for greener pastures, leaving Manhunt (which, by this time, had changed editorial hands a few times) to lesser known scribes. The once great magazine saw a continuing downward spiral of quality and sales, resorting, in the last few years, to reprinting some of the classics that put them on the map in the first place. That’s a very sketchy and obviously truncated version of the history of Manhunt, which brings me to this column. Steve Lewis has been kind enough to let me share my obsession (and make no bones about it, this is an obsession) with the readers of Mystery*File. So what will make up this column and why should you care? I frequent a lot of book shows, and I see a lot of outrageous prices on these things. Should you fork over $40 for a July 1960 Off-Beat Detective (no, you shouldn’t), or $30 for a May 1961 Web Detective (yes, you should)? Will owning a full set of The Saint make you a better person (no, it won’t), or should you just settle for the four issues of Justice (yes, you should)? The meat of this first column contains a story-by-story guide to the first issue of Manhunt, consisting of title, author, word count, a short summary (sometimes very short so not to spoil), critical comments, and a little background on the author when I can provide it. I don’t always provide all of the above, since it’s hard to give a detailed description of a 1000-word story, and one-hit wonders like Sam Cobb pretty much disappeared after their moment of glory. Every other column will be dedicated to a successive issue of Manhunt. In the alternating installments, you’ll be treated to the delights of Don Pendleton’s Executioner, Mystery Monthly, Two-Fisted Detective, or any one of the literally thousands of digests sitting atop my long shelf. I’ll cover two or three random issues per column, and we’ll all discover the delights that may have otherwise been overlooked in a musty corner of Aunt Addie’s Antiques, or offered for wayyyy too much dough on eBay. By the way, I’d love to hear from fellow Digestaholics. You can reach me by clicking here. MANHUNT Vol. 1,

No. 1 January 1953

Everybody’s Watching Me, by Mickey Spillane (a serial in four parts) (29,500 wds total) ** Joe Boyle stumbles into bigtime trouble when he delivers a message to mobster Mark Renzo from fellow mob man Vetter. After using his face and most of his body to stop the fists of Renzo’s goons, Boyle finds himself in the helpful, loving arms of a tomato known as Helen Troy (or as her late night patrons call her, Helen OF Troy). Together the two fall in love and into other dangerous situations. In the 1950s, no one sold more gritty, hardboiled fiction than Mickey Spillane. I, the Jury (1947), My Gun Is Quick (1950), The Long Wait (1951), The Big Kill (1951), Vengeance Is Mine (1951), One Lonely Night (1951), and Kiss Me, Deadly (1952) all sold millions of copies while pushing the boundaries of violence and sex in mainstream fiction. The American Booksellers Association reported that only the Bible outsold Spillane in 1952. His character Mike Hammer (“hero” of all the aforementioned novels except The Long Wait) bedded women and broke teeth like no other popular creation before him. Hammer’s translation to the big screen was equally popular (Robert Aldrich’s version of Kiss Me, Deadly with Ralph Meeker, is regarded by many as the greatest noir film of all time), with new movie and TV adaptations popping up every couple years. Without Spillane’s massive popularity, it’s unlikely that publishers like Gold Medal and Lion would have taken a chance on such hardboiled writers as Gil Brewer, Vin Packer, Jim Thompson, and David Goodis, and even more unlikely that Flying Eagle would have launched Manhunt. It’s appropriate that Spillane should lead off the premiere issue. Despite his popularity, Spillane had many detractors (most of them literary critics (Footnote 1) ) who decried the Mick’s blend of blood and bosoms. Spillane is definitely an acquired taste, one that either hooks you immediately or turns you off. Whatever it was he had, it appealed to an enormous amount of readers, as Spillane quickly became the biggest selling hardboiled author in the middle sector of the 20th century. Die Hard, by Evan Hunter (7000 wds) *** Matt Cordell, ex-PI, current drunk, is asked by Peter D’Allessio to save his son Jerry, whose life has become a nightmare of heroin addiction. Cordell initially turns down the request but reconsiders when the elder D’Allesio is gunned down in front of him. Cordell finds that there’s a hell even worse than the one he occupies. Cordell is an ex-private investigator who lost his license after beating his wife’s boyfriend and now finds his solace on a barstool. All six of the Matt Cordell stories have basically the same framework: Cordell is either drunk or in the process of becoming so when someone approaches him to take on a case. He first refuses, then relents, usually after a drink. He makes love to, or assaults, every woman that crosses his path, depending on their intentions. He gets shot a few times. He has a few more drinks. He solves the case. He heads for the next bar. Ed McBain’s style and trademarks show through in his Cordell stories. The graphic sense of violence (particularly in “Dead Men Don’t Dream,” where the reader discovers Cordell’s fondness for breaking bones), the “you are there” feel to his descriptions of the city, and the staccato dialogue – all could have been lifted from any one of the novels set in McBain’s justifiably famous 87th Precinct. Because the set-ups are so similar, it is probably a good idea for the reader to space these stories out rather than reading them in one sitting. Perhaps this is why McBain abandoned the Cordell character after just a handful of short stories and one novel (I’m Cannon – for Hire, published by Gold Medal in 1958, wherein Cordell, renamed Cannon, is hired to protect a man from a killer). Cordell’s descent into a bottle full of Hell is not pretty and probably wasn’t a lot of fun to write about either. (Footnote 2.) I’ll Make the Arrest, by Charles Beckman, Jr. (4000 wds) ** Well-known actress Pat Taylor is strangled, and the cop investigating the murder happens to be the corpse’s old beau. This cop is determined not to take prisoners. Charles Beckman wrote seven stories for Manhunt in the first two years of the magazine’s existence, as well as stories for Pursuit (“A Hot Lick for Doc”), Double-Action Detective, Trapped, Mystery Tales (“Nymph in the Keyhole”) and Popular’s pulp Detective Tales (with wonderful titles such as “Die-Die Baby” and “Doll, Drop Dead!”). He also wrote the novel Honky Tonk Girl, which would probably be forgotten if it wasn’t published by the notoriously collectible Falcon Books in 1953. Falcon published digest-sized paperbacks, and Honky Tonk Girl would prove to be their last. (Footnote 3.) The Hunted, by William Irish (10,000 wds) * A woman is falsely accused of murder in a geisha house and is aided by a sailor on shore leave. William Irish was a pseudonymn of Cornell Woolrich, the highly-regarded mystery writer who found major success in the 1940s in print and on radio. Woolrich’s dramas became a mainstay of such radio shows as Escape and Suspense. “The Hunted” is not a very good story. It’s rife with dull, cliched dialogue and inexplicable plot twists and deux ex machinas. The entire story reads almost like a radio drama: the events occur only long enough to get to the end of an hour. It’s also (in these PC times) insanely racist: Character to his Chinese landlord: “How do you find an address in a hurry?” Landlord: “You ask inflammation lady at telephone exchange.” Then again, Francis M. Nevins writes in his book-length biography of Woolrich, First You Dream, Then You Die, that the story is “a fine action whizbang.” An interesting footnote to the story is that in 1953, when the editors of Manhunt were putting together the premiere issue, they solicited a story from Woolrich and received “The Hunted,” purported, by Woolrich, to be a brand new story. It was only after the publication that a reader wrote in to Flying Eagle to report that the story was actually a reprinting of a story that appeared in a 1938 issue of Argosy with the title of “Death in Yoshiwara.” Nevins writes that the editors of Manhunt “were not amused.” The Best Motive, by Richard S. Prather (5500 wds) *** One of my favorite PI’s, Shell Scott, tackles the case of the stalker and the stalkee. Luscious newlywed Ellen appeals to Scott’s good samaritan side (and his libido as well) when it appears she’s being stalked by a crazed ex-boyfriend. A couple of really good highlights in “The Best Motive” illustrate why Shell Scott was such a popular PI in the PI-infested 1950s: After Shell is forced to abandon his car as it’s ripping through a guardrail over a cliff and into the sea, he remembers locking an unfortunate thug in the trunk; and the bar that Scott frequents, “The Haunt,” is populated by waiters dressed as skeletons. Shell Scott not only starred in 35 novels, but several short stories (collected in the Gold Medal paperbacks Three’s a Shroud, Have Gat – Will Travel, The Shell Scott Sampler, and Shell Scott’s Seven Slaughters) and achieved what only a few other PI’s can brag about: their own magazine. Shell Scott’s Mystery Magazine presented (albeit briefly, issuing only nine issues from February through November 1966) such Manhunt authors as Jonathon Craig, Hal Ellson, John D. MacDonald, and Henry Kane, as well as spotlighting a Shell Scott “short novel” each issue. When SSMM went bellyup (due to poor sales), creator Richard Prather was not even informed that the magazine had been discontinued and was not paid for quite a bit of the fiction that he had written for the digest. A tenth issue was prepared but never released. (Footnote 4.) Shock Treatment by Kenneth Millar (5000 wds) ** Evelyn, the wealthy heiress and Tom, her newlywed husband (the requisite gigolo) enjoy a weekend in the woods until Evelyn goes into diabetic shock. Will Tom show his true colors or true love? Told entirely in dialogue, an interesting experiment, with Evelyn coming off as a shrewish Lucille Ball. Kenneth Millar later went on to acclaim as (John) Ross MacDonald, creator of Lew Archer, the PI of The Moving Target and The Drowning Pool (both of which were made into movies starring Paul Newman). His wife was the successful mystery writer, Margaret Millar. Author Bill Pronzini writes that MacDonald’s Lew Archer, Private Investigator “ranks with Hammett’s Continental Op collections and Chandler’s Simple Art of Murder as the finest volumes of so-called hard-boiled crime stories.” (Footnote 5.) The Frozen Grin, by Frank Kane (8500 wds) ** Private eye Johnny Liddell helps the DA investigate the murder of a prostitute. Really nothing special, “The Frozen Grin” is a typical tale with dumb heavies, broads with big breasts, and henchmen who can’t shoot (or stab) straight. That said, I have a special fondness for Liddell, due mostly to his Dell paperback series of the 1960s. With titles like A Real Gone Guy, Trigger Mortis, Bare Trap, and atmospheric covers (by artists such as Bill George, Victor Kalin, Harry Bennett, Robert Stanley, and king of the noir, Robert McGinnis), these books are a collector’s treasure. Frank Kane (1912-1968) had a freewheeling style of writing. It seemed to be all over the place at the same time. He could write dark: There

was a dull, crunching sound as the man’s nose broke. Liddell

chopped

down at the exposed back of the other man’s neck in a vicious rabbit

punch. Sammy hit the floor, face first. Didn’t move.

or light: She

slid out of his arms, shrugged her shoulders free of the gown. It

slid down past her knees, and she stepped out of it. Her breasts

were full, pink tipped; her waist trim and narrow. Her legs were

long, tapering pillars; her stomach flat and firm.

Her eyes dropped down to her nakedness, rolled up to his face. “I’ll do my best to make sure you’re not bored, Johnny.” Frank Kane’s famous creation didn’t dip his toes solely in the Manhunt waters. In addition to the 19 stories published in Manhunt, Liddell starred in 29 novels from 1947 (About Face) to 1967 (Margin for Terror) and several short stories in that same span. Liddell stories could be found in Ed McBain’s Mystery Book, Mike Shayne, Accused, The Saint, and Crack Detective Stories. In total, sixteen of Liddell’s cases (six from Manhunt) were collected in Johnny Liddell’s Morgue (Dell, 1956) and Frank Kane’s Stacked Deck (Dell, 1961). Kane wrote two books under the pseudonym of Frank Boyd: The Flesh Peddlers (Monarch, 1959) and Johnny Staccato (Gold Medal, 1960), the latter a TV tie-in of an offbeat series starring John Cassavetes as Staccato, a private investigator who moonlights as a jazz pianist. The program lasted only one season but boasted a veritable who’s who of TV among its guest stars: Michael Landon, Elizabeth Montgomery, Cloris Leachman, Mary Tyler Moore, and Cassavetes’ real-life wife, Gena Rowlands. Kane cut his literary teeth in the pulps and on radio, where from 1945 to 1950 he wrote over 40 scripts for The Shadow (with wonderfully pulpish titles such as “Etched With Acid,” “Unburied Dead,” and “Scent of Death”). The author also created, wrote, and produced the TV show Claims Agent, based on his own character, Jim Rogers. Backfire, by Floyd Mahannah (22,000 wds) **1/2 Pete Mavrey meets a beautiful but troubled woman named Bernice Falkner. Bernice has been harrassed by an ex-boyfriend and, attempting to escape him forever, fakes her own death. She then contacts Pete and drags him down into her web of deceit, murder, blackmail, and other general nasty stuff. “Backfire” has an interesting premise that is well-executed during its first three quarters, but then suffers from way too much expository and a ludicrous wrap-up. Mavrey’s one of those likeable charcters that always seems to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Floyd Mahannah (1911-1976) wrote five crime novels: The Yellow Hearse (1950), The Golden Goose (1951), Stopover for Murder (1953), The Golden Widow (1956), and (1957). His first published short story appeared in the June, 1949 issue of The Broken AngelEllery Queen (“Ask Maria”). The Set-Up by Sam Cobb (1500 wds) ** Short-short about a crime beat reporter and his financial woes. Answering a strangulation murder, he discovers a way out of his monetary mess. As an author, Cobb turns out to have been a brick wall for me. I’ve checked all of the paperback, mystery, western, horror, and mainstream reference books, plus the web, and I found that there's more information on the web for me than this guy! He did contribute a story called “Cheat” to the short-lived digest, Private Eye (two issues, both in 1953), and then disappeared from the literary landscape forever. Footnotes (1) In his biography of John D. MacDonald, Hugh Merrill writes that “John D. MacDonald returned hard-boiled writing to the realm of literature and pulled it from the sewer of sadism where (Mickey) Spillane had dragged it.” (The Red Hot Typewriter: The Life and Times of John D. MacDonald, St. Martin’s Press, 2000, p.2 ). (2) An interesting aside is that when Gold Medal collected six of the eight Cordell stories (the only two excluded are “Return” and “The Beatings”) in I Like ’Em Tough (Gold Medal, 1958) and the subsequent novel, Evan Hunter’s fifth pseudonym, Curt Cannon, was created (sixth pseudonym actually, since Hunter/McBain was born Salvatore Lombino). I assume this change was made because Hunter, at the time, was publishing novels of a more literary slant such as The Blackboard Jungle and Mothers and Daughters. Hunter would use the pseudonyms Ezra Hannon (Doors, 1975) and John Abbott (Scimitar, 1993) later in his career. When Warner reprinted their paperback of Doors in the 1980s, they changed the cover to read “Ed McBain” rather than “Ezra Hannon” to cash in on the success of the 87th Precinct, but forgot to change the author’s name on the title page! The entire oeuvre of Lombino- McBain- Hunter- Marsden- Collins- Cannon- Hannon- Abbott is a long and winding maze, and a complete bibliography would be a welcome addition to my shelf. (3) The most collectible Falcon digest is The Evil Sleep! by Evan Hunter. Though it’s been reprinted (as So Nude, So Dead by Richard Marsten), it still fetches several hundred dollars from collectors when it can be found. (4) The info about Shell Scott’s Mystery Magazine was provided to this writer by Richard Prather while I was preparing a “Shell Scott” issue of my defunct magazine, bare*bones. More info can be found in bb Vol. 1, Number 2 (Spring 1998). (5) Bill Pronzini in 1001 Midnights (Arbor House, 1986), pages 525-526. For my money, this is the best mystery reference book on my shelf. Comprised of lengthy reviews of over 1000 important crime novels, 1001 Midnights is indispensable to both beginning and veteran readers of mystery fiction. EDITORIAL POSTSCRIPT. Concerning the mysterious Sam Cobb, I decided to work on the possibility that it was a pen name for someone else whose work was in the same issue, the editor not wanting to have two stories appearing as by the same person in the same magazine. Now going to the contents page of the July 1953 issue of Private Eye (also the first issue of that magazine), who else had stories besides the unknown Cobb? And, more importantly, which authors overlapped and were in both of the two issues in which “Cobb” appeared? Answer: Ed McBain had a story in Manhunt #1, and “Hunt Collins” (aka Ed McBain) had a story in story in Private Eye #1. What do you think? Do two and two make four, or twenty-two? Note: Later installments of this column can be found be going here. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. stevelewis62 (at) cox.net This column previously appeared in Mystery*File 47, February 2005. Copyright © 2005 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

Return to

the Main Page.

|