|

MacKINLAY KANTOR AND THE POLICE NOVEL

by John Apostolou  Although no

mystery writer has ever won a Pulitzer Prize, some recipients of this

prestigious award have written mysteries. Among the Pulitzer

winners who have contributed to our genre are William Faulkner, John P.

Marquand, Norman Mailer, and the author whose work is discussed in this

essay – MacKinlay Kantor.

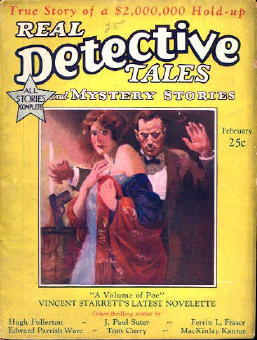

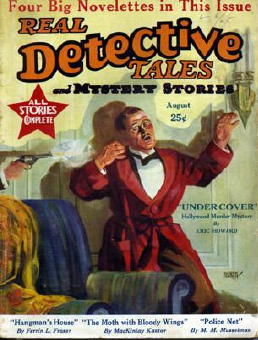

SOURCES:A popular and prolific author, MacKinlay Kantor produced some fifty books of fiction and nonfiction as well as hundreds of short stories and magazine articles. He was a newspaper reporter, a screenwriter, a poet, a war correspondent, and, above all, a writer of historical fiction about the American past. His crowning achievement was Andersonville, a Civil War novel about an infamous Confederate prison camp, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1956. PULP STUFF Little remembered today is the fact that MacKinlay Kantor wrote a considerable amount of crime fiction, most of it appearing in pulp magazines during the years 1928 to 1934. While struggling to establish himself as a writer, he turned out dozens of stories for the crime pulps. His first pulp stories, “Delivery Not Received” and “A Bad Night for Benny,” were purchased by Edwin Baird, editor of Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories. Paid at the rate of one cent a word, Kantor received a check for only $36. Real Detective Tales, a lesser-known pulp, was published in Chicago. Robert Sampson tells us that the stories in this magazine “emphasized amateur investigators of remarkable mental abilities and adventures among the gangsters of the Prohibition era. The action was brisk, the scene contemporary.’” [FOOTNOTE 1.] Frequent contributors included Vincent Starrett, Seabury Quinn, and Eric Howard.  Several of the stories

Kantor wrote for Baird were

horror tales, with such titles as “The Thing in the Tunnel” and “Three

Men Hanging.” On one occasion, Baird asked him if he could do a

novelette based on an existing piece of cover art. Kantor

accepted the assignment and wrote “The Chicago Racket,” as by Joe

Feeney, in two days. His best stories from this period are “The

Second Challenge,” which featured a railroad detective, and “The Light

at Three O’Clock,” a locked room mystery. Both stories have often

been reprinted. Several of the stories

Kantor wrote for Baird were

horror tales, with such titles as “The Thing in the Tunnel” and “Three

Men Hanging.” On one occasion, Baird asked him if he could do a

novelette based on an existing piece of cover art. Kantor

accepted the assignment and wrote “The Chicago Racket,” as by Joe

Feeney, in two days. His best stories from this period are “The

Second Challenge,” which featured a railroad detective, and “The Light

at Three O’Clock,” a locked room mystery. Both stories have often

been reprinted.Kantor churned out pulp fiction to support himself and his family, while devoting his major effort to producing mainstream novels: Diversey, El Goes South, The Jaybird, and an unpublished novel, Half Jew. His attitude toward writing for the pulps is revealed in the following quote: I wrote it [“The Light at Three

O’Clock”] in a solitary few hours of

a single day, when I had fled to my workroom after reading the morning

mail. Bills, nothing but bills; necessity, nothing but

necessity. I had to get another check within a few days. My

typewriter was the only machine for manufacturing it. FOOTNOTE 2.

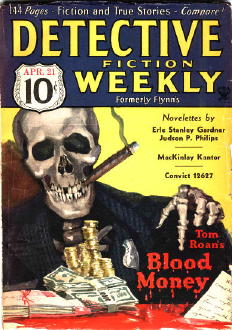

Eventually Baird raised Kantor’s rate to two cents a word, but one day in Baird’s office, the editor announced he was lowering the rate back to a cent a word. Kantor stalked out, never to write for Real Detective Tales again. He continued, however, to write for the pulps, mainly for Detective Fiction Weekly. His fortunes as a writer were improving. He moved from the Midwest to New Jersey in 1932 and was now represented by a first-rate New York agent, Sydney Sanders. The editor of Detective Fiction Weekly, Howard Bloomfield, liked Kantor’s work and purchased sixteen of his short stories and a serialized novel in less than two years. The following excerpts from a profile, probably written by Bloomfield, gives us a picture of Kantor at age 29: Mr. Kantor is an extraordinary young man,

and probably the one writer we know who really looks like a

writer. Tall, loose-jointed, horn-rimmed glasses, long brown

hair, he emerges periodically from New Jersey with a brief case under

his arm and a pipe in his mouth. ... One of his passions is

playing a guitar; another is reading histories of the Civil War; and a

third is playing the fife. FOOTNOTE 3.

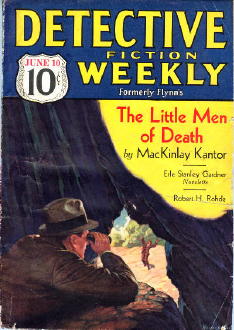

The one novel Kantor wrote for Bloomfield was printed in five parts and titled “The Little Men of Death” (June 10-July 8, 1933). Kantor relates a bizarre tale of poison darts and voodoo vengeance, with the action taking place in the wilds of New Jersey. It begins with explorer Edwin Garris being erroneously reported dead. The false report providing him virtual anonymity, Garris conducts a battle against “the little men of death,” sinister beings from the Peruvian jungle. The novel, though essentially a potboiler, is a smooth, well-written example of thriller fiction.  During his long writing career, Kantor displayed little interest in series characters, but he did write three police stories featuring the Glennan brothers for Detective Fiction Weekly. The titles are “Sparrow Cop” (Mar. 18, 1933), “The Trail of the Brown Sedan” (January 6, 1934), and “The Hunting of Hemingway” (April 21, 1934). These stories, reprinted years later in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, represent the best work Kantor ever did for the pulps. Although he did not think highly of his pulp work, Kantor wrote that the second Glennan brothers story “has a kind of sharpness and pungency not always found in pulp magazine material.” [FOOTNOTE 4.] The same comment could be made about the other two stories. Drawing upon his experience as a news reporter, Kantor was able to create exciting police yarns, realistic in tone. The Glennan brothers, Nick and Dave, are members of a big city police department. Nick, who often displays courage and deductive skill, is the main character, while his older brother, Dave, plays a lesser role as a hardworking detective sergeant. The three stories, taken together, could be considered a novella chronicling Nick’s rise from the rank of a rookie cop, walking his beat in a city park, to that of a highly regarded police detective. Kantor wrote a few other police stories, but most of his tales for the pulps are of the surprise-ending type popularized by O. Henry. Plots are often farfetched and make liberal use of coincidence, with the settings usually in rural areas or small towns. The Glennan brothers trilogy, however, is a real achievement, clearly a forerunner to today’s police procedural novels. Authorities on the police procedural have unfairly neglected the contributions of Kantor, Frederick Nebel, Victor Maxwell (probably a house name), and other pulpsters in the early development of that subgenre. Kantor’s pulp stuff, although not on a par with the work of Hammett and Chandler, is certainly superior, especially in characterization, to most pulp era fiction. But Kantor had no illusions about the quality of his pulp stories. In 1940, looking back on his early career, he made this candid, though overly modest, assessment: I used to write a great deal of stuff for

the pulp detective-and-crime story magazines, in the years when I had

to make a living that way, and I don’t think that my rather complicated

talents were harmed in the least. The severe routine of such

endeavor stimulated my sense of plot and construction, which needed

such stimulation very badly indeed. I was well aware that the

stuff I wrote had little value, except in most cases it made

entertaining narrative. FOOTNOTE 5.

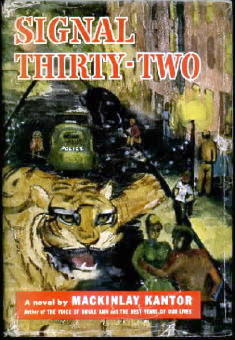

POLICE WORK In 1934, MacKinlay Kantor experienced his first major success with the publication of Long Remember, an historical novel concerning the Battle of Gettysburg. Now enjoying a degree of popularity, he ceased writing for the pulps and began submitting short fiction to the slick magazines. Only a few of his slick stories fall in the crime category; two worth mentioning are “Rogues’ Gallery” (Collier’s, August 24, 1935) and “Gun Crazy” (Saturday Evening Post, February 3, 1940). “Rogues’ Gallery,” a tale about the murder of a sculptor who leaves an elaborate dying clue, became Kantor’s most frequently reprinted short story. “Gun Crazy” served as the basis for a low budget movie with the same title, now considered a film noir classic. The movie was directed by Joseph H. Lewis and released in 1950. The screen credits indicate that the script was written by Kantor and Millard Kaufman; however, it was revealed in 1992 that Kaufinan had acted as a front for black listed writer Dalton Trumbo. When World War II ended, Kantor showed his concern with the problems faced by returning veterans in the novel Glory for Me, written in verse. The book was adapted to the screen as The Best Years of Our Lives, winner of seven Academy Awards. In the years following the war, Kantor was one of several writers who brought realism to the portrayal of police work. Lawrence Treat, Hillary Waugh, and John Creasey began writing police procedural novels, the first being Treat’s V As in Victim, published in 1945. Sidney Kingsley’s drama DETECTIVE STORY opened on Broadway in 1949, and in the same year, Jack Webb’s Dragnet reached the public in its initial form as a radio series.  In 1948, Kantor began a

fifteen-month period of

intensive research into the world of cops. He had received

permission from Thomas Mulligan, the Acting Police Commissioner of New

York City, to accompany police officers during all their activities, a

privilege never afforded to any civilian, other than a working

journalist. Kantor chose to concentrate on the 23rd Precinct,

which included posh apartments on upper Park Avenue as well as the

slums of East Harlem, a high-crime area then absorbing a massive wave

of immigration from Puerto Rico. Taking full advantage of his access to

police facilities, he soon made friends with senior officers and

patrolmen, and frequently rode in prowl cars during regular duty tours. In 1948, Kantor began a

fifteen-month period of

intensive research into the world of cops. He had received

permission from Thomas Mulligan, the Acting Police Commissioner of New

York City, to accompany police officers during all their activities, a

privilege never afforded to any civilian, other than a working

journalist. Kantor chose to concentrate on the 23rd Precinct,

which included posh apartments on upper Park Avenue as well as the

slums of East Harlem, a high-crime area then absorbing a massive wave

of immigration from Puerto Rico. Taking full advantage of his access to

police facilities, he soon made friends with senior officers and

patrolmen, and frequently rode in prowl cars during regular duty tours.The end result of his research was a major novel, Signal Thirty-Two, published in 1950 with jacket art by the author’s wife, Irene Layne Kantor. The title refers to a phrase used on police radio that simply means “Assist Patrolman” or “Investigate” but implies danger and extreme emergency. In Signal Thirty-Two, Joe Shetland and Dan Mallow are partners who patrol the streets of the 23rd Precinct in a police car. Shetland is an experienced cop; Mallow is a rookie. As in the Glennan brothers stories, the younger man learns what it is to be a cop and proves himself in the course of a number of incidents – some dangerous, some routine. Other important characters are Blondie Dunbar, a rookie cop with whom Mallow served in Europe during the, war, and Dunbar’s sister, Ellie, who becomes Mallow’s wife. Kantor weaves three threads through the book: the day-to-day police work of Shetland and Mallow, the sometimes strained relationship between Mallow and Ellie, and Dunbar’s use of illegal methods to earn a promotion to detective. Mallow’s love affair with Ellie and their marital problems seem tame by today’s standards, and Dunbar’s transgressions never develop into a truly dramatic situation. The novel is most effective when it presents us with realistic accounts of policemen on patrol and their encounters with criminals. These may have been events Kantor had actually observed. Memorable passages depict an exciting chase across tenement rooftops in pursuit of rape suspects, a frantic attempt to save the life of an emaciated infant, and a dramatic gunfight between Shetland and a thief on a crowded bus. In each of these rather long passages, Kantor makes use of heightened language in a powerful stream-of-consciousness style. Since the novel features uniformed policemen and contains no mystery to be solved, Signal Thirty-Two does not quality, by the definition fonnulated by Hillary Waugh and George Dove, as a police procedural. To use an analogy from television, the novel is closer to Adam 12 than to Dragnet. What Kantor gives us is a police novel, perhaps the first novel to take a probing look into the police subculture. Signal Thirty-Two is a forerunner to Joseph Wambaugh’s The New Centurions and Dorothy Uhmak’s Law and Order, but without the rough language and sexual frankness one finds in modem fiction. Kantor was greatly impressed by the dedication and valor of the men in the NYPD, especially the World War II veterans who formed a majority of the police force at that time. He thought being a cop was more than a job to these veterans. In a nonfiction piece for True magazine, he wrote that they were motivated by “a peculiar curiosity-a desire to observe and share the heartbeat of human existence.” FOOTNOTE 6. Some errors about Kantor’s work have crept into mystery reference books. Diversey, his first novel, is erroneously called a crime novel about Chicago gangsters. The gangster characters playa small part in the book, which is clearly not a crime novel. Kantor’s novel Midnight Lace has also been incorrectly labeled a crime novel because it has the same title as a 1960 thriller movie, which starred Doris Day. But there is absolutely no connection between Kantor’s book and the film MIDNIGHT LACE. The film is based on a play by Janet Green.  A FULL AND ACTIVE LIFE After winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1956, MacKinlay Kantor became a minor celebrity. He sold Andersonville to Hollywood for a substantial sum, received several honorary degrees, and continued to write historical novels, the most notable being Spirit Lake, the story of an Indian raid on settlers in Iowa. Collections of his magazine articles and short fiction were published, including a 1960 paperback collection of his crime stories, It’s About Crime. Among Kantor’s favorite subjects were the Civil War and the U.S. Air Force. In a letter to a friend, Ernest Hemingway wrote that Kantor “would be a pretty fair country writer if he would just resign this commission in the Confederate Air Force.” [FOOTNOTE 7.] Although this remark seems rather condescending, Kantor would often quote it with pride and amusement. Kantor was a colorful character who led a full and active life. He loved America and was devoted to his family. He had a fondness for dogs and a fascination with guns. He enjoyed singing and playing the guitar. A bit of a performer, Kantor took part in reenactments of Civil War battles and played a small role in the movie WIND ACROSS THE EVERGLADES. More infornlation about his life, the good times and the bad, can be found in My Father’s Voice: MacKinlay Kantor Long Remembered, a 1988 biography/memoir by his son, Tim Kantor. No attempt will be made here to evaluate MacKinlay Kantor’s place in the broader field of American literature. My purpose is a limited one: to bring Kantor’s crime fiction, especially the Glennan brothers trilogy and Signal Thirty-Two to the attention of mystery fans. Although Kantor is certainly remembered by Civil War buffs, most readers today are unaware of his work in our genre. Besides producing entertaining crime fiction, Kantor gave us a book, Signal Thirty-Two, that deserves to be recognized as an important contribution to the development of the police novel.  NOTES NOTES1. Robert Sampson, “Detective Tales (Rural Publications),” entry in Mystery, Detective, and Espionage Magazines, edited by Michael L. Cook (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983), p. 158. 2. McKinlay Kantor, “Bills, Nothing but Bills,” Story Teller (NY: Doubleday, 1967), p. 44. 3. “Flashes from Readers,” Detective Fiction Weekly, 10 June 1933, p. 140. 4. Kantor, “Jersey City Cops,” Author’s Choice (NY: Coward-McCann, 1944), p. 121. 5. Kantor, quoted in Kantor entry in Contemporary American Authors, by Fred B. Millett (NY: Harcourt, Brace, 1940), p. 414. 6. Kantor, “Two Cops of the Twenty-Third.” True, December 1950, p. 104. 7. Ernest Hemingway, quoted in a letter from John D. MacDonald to this author, 31 December 1984. This article first appeared in slightly different form in The Armchair Detective, Volume 30, Number 2, Spring 1997. Copyright © 1997, 2006 by John Apostolou. A

CHECKLIST

OF CRIME FICTION BY

MacKINLAY KANTOR

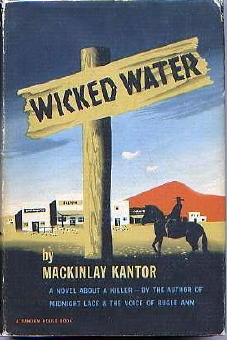

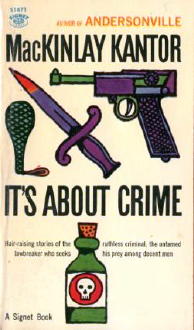

by John Apostolou & Steve Lewis. NOVELS  “The Little Men of Death.” Serialized in Detective Fiction Weekly, June 10-July 8, 1933. Wicked Water. Random House, hc, 1948. [Historical novel, US West, 1899: “The battle between cattle barons who want the land left open for their cattle and the killer they hire to convince the homesteaders to keep moving.”] Unicorn Mystery Book Club #40, hc reprint: four-in-one edition, April 1949. Bantam 809, pb, 1950. Bantam1238, 2nd pr., 1954. One Wild Oat. Gold Medal #122, pbo, 1950. Gold Medal 122, 2nd pr., 1951. Gold Medal 675, 3rd pr., 1957. Gold Medal s1181, 4th pr. 1961. Signal Thirty-Two. Random House, hc, 1950. Book club edition, hc reprint. Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, hc reprint: multi-title volume, Winter 1951. Bantam A965, pb, 1952. Bantam F2029, later pr., February 1960. STORY COLLECTIONS Author’s Choice. Coward-McCann, hc, 1944. Armed Services Editions #813, pb, October 1945. Contains 40 stories, 5 of which are criminous: “The Second Challenge.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, February 1929. “Neither Hand Nor Foot.” Detective Fiction Weekly, August 6, 1932. “Trail of the Brown Sedan.” Detective Fiction Weekly, January 6, 1934. [Nick & Dave Glennan.] “Rogues’ Gallery.” Collier’s, August 24, 1935. “Gun Crazy.” Saturday Evening Post, February 3, 1940.  It’s About Crime. Signet S1871, pbo, 1960. Contains 11 crime stories: “Rogues’ Gallery.” Collier’s, August 24, 1935. “Nobody Saw Him Fall.” Detective Fiction Weekly, December 23, 1933. “The Shadow Points.” Dime Detective, March 1, 1933. “Sparrow Cop.” Detective Fiction Weekly, March 18, 1933. [Nick & Dave Glennan.] “The Grave Grass Quivers.” The Elk’s Magazine, July 1931. “The Strange Case of Steinkelvintz.” Chicago Daily News Midweek, 1929. “Something Like Salmon.” Detective Fiction Weekly, August 19, 1933. “Blue Jay Takes the Trail.” Complete Stories, 1933. “The Light at Three O’Clock.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, July 1930 “Wolf! Wolf!” Real Detective, 1932. “The Watchman.” Collier’s, 1936. Story Teller. Doubleday, hc, 1967. No paperback edition. Contains 23 stories, 2 of which are criminous: “The Light at Three O’Clock.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, July 1930. “Maternal Witness.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, August 1930. UNCOLLECTED DETECTIVE PULP FICTION [This section may easily be incomplete.] “A Bad Night for Benny.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, March 1928. “Delivery Not Received.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, April 1928. “The $10 Thousand Bag.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, June 1928. “This Guy Baum.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, July-August 1928. “Three Cheers for Justice.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, September 1928. “The Bug Catcher.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, October 1928. “The Kidnapped Alphabet.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, Dec 1928-Jan 1929. “When St. Peter Descends.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, March 1929.  “Three Men

Hanging.” Real Detective Tales

and Mystery Stories, April-May 1929. “Three Men

Hanging.” Real Detective Tales

and Mystery Stories, April-May 1929.“Ballots and Bullets.” Munsey’s, June 1929. “The Moth with Bloody Wings.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, August 1929. “Damon and the Demon.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, September 1929. “The Return of Danny Eggers.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, October 1929. “Watchman Wanted.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, February 1930. “A Check from the Deceased.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, April 1930. “Death in the Evening.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, May 1930. “The House with the Animal in It.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, September 1930. “Spooks in the Night.” Clues, 1st November, 1930. “Death Beneath the Hood.” Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, January 1931. “The Beast That Was Black.” Detective Fiction Weekly, September 3, 1932. “Packet of Death.” Detective Fiction Weekly, September 17, 1932. “The Sickle and the Hounds.” Detective Fiction Weekly, October 1, 1932. “The Body in the Flume.” Detective Fiction Weekly, October 15, 1932. “Death Grew on the Ground.” Detective Fiction Weekly, October 29, 1932. “The Cannon Kills.” Clues, November 1932. “The Torture Pool.” Detective Fiction Weekly, November 12, 1932. “The Painted Throat.” Detective Fiction Weekly, January 28, 1933. “Shot at Seven.” Dime Detective, June 1, 1933. “The Critter with Claws.” Detective Fiction Weekly, June 23, 1933. “Corpses Sat in the Car.” Detective Fiction Weekly, September 23, 1933. “Peg Leg.” Detective Fiction Weekly, April 14, 1934 . “The Hunting of Hemingway.” Detective Fiction Weekly, April 21, 1934. [Nick & Dave Glennan.] Bill Contento, The FictionMags Index. Michael L. Cook & Stephen T. Miller, Mystery, Detective and Espionage Fiction (1915-1974). Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV. www.abebooks.com YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Copyright ©

2006 by John Apostolou & Steve Lewis.

|