|

IN THE FRAME, by Vince Keenan

BOOKS

You know you’re in the

hands of a truly unscrupulous narrator when a priest meeting him for

the first time says, “You’re a bad egg. As bad as they come.” The

description suits Giorgio Pellegrini, the protagonist of Massimo

Carlotto’s The Goodbye Kiss.

This novel, originally published in 2000, is the latest example of

“Mediterranean noir” from Europa

Editions. You know you’re in the

hands of a truly unscrupulous narrator when a priest meeting him for

the first time says, “You’re a bad egg. As bad as they come.” The

description suits Giorgio Pellegrini, the protagonist of Massimo

Carlotto’s The Goodbye Kiss.

This novel, originally published in 2000, is the latest example of

“Mediterranean noir” from Europa

Editions.Giorgio, wanted for political crimes committed half-heartedly in his native Italy, has decided that seven years on the run is enough. He blackmails his old contacts in the movement into delivering “the best deal on the bad rep market.” Once he’s paid his debt to society, Giorgio sets out to earn a little bourgeois respectability for himself using the only tools at his disposal: an utter lack of morals and an eye for opportunity. In short order, he’s forcing other ex-revolutionaries to commit hold-ups for him and cheating the spectacularly crooked cop with whom he’s made a devil’s pact. (“Something about him always made me think he was rotten. Not just corrupt. Rotten. The right sort of guy to form a partnership with.”) Carlotto, a former left-wing militant, fugitive, and convict, knows whereof he speaks. He also writes like an unholy combination of Patricia Highsmith and Jim Thompson. When so many contemporary noir authors wallow in darkness for its own sake, Carlotto makes sure that every shadow in his book is cast by forces either psychological or political. Giorgio is no posturing tough guy but a genuine sociopath, issuing immediate assessments (“Somewhere along the way she registered it was too late to get back to even a vague facsimile of the woman she once was”) and acting on them with ruthless precision (“All she lacked was a violent, unjust death, and I’d provide that very soon”). Even more chilling is Giorgio’s pursuit of success in the new Europe with a zeal he only pretended to feel for the ideals of his youth. Carlotto has concocted an elegant thriller that also paints a scabrous picture of a society that has lost its moral bearings. Europa Editions is not only publishing recent foreign fiction. The company is also reissuing older titles that have been unfairly neglected. Patrick Hamilton’s work as a playwright produced the landmark suspense films ROPE and GASLIGHT. Now his 1941 novel Hangover Square is back in print.  Shy, hulking George Harvey

Bone has suffered from “dead moods” all his life. With a ‘click,’

his consciousness slips and he becomes someone else. “Imagine it

– wandering about like an automaton, a dead person, another person, a

person who wasn’t you, for twenty-four hours at a stretch!” The

moods are exacerbated by his feelings for would-be actress Netta

Longdon, a denizen of the Earl’s Court neighborhood of London.

“You might say he wasn’t really ‘in love’ with her: he was ‘in hate’

with her. It was the same thing – just looking at his obsession

from the other side.” One version of George vows to win Netta’s

heart. The other is determined to kill her. Shy, hulking George Harvey

Bone has suffered from “dead moods” all his life. With a ‘click,’

his consciousness slips and he becomes someone else. “Imagine it

– wandering about like an automaton, a dead person, another person, a

person who wasn’t you, for twenty-four hours at a stretch!” The

moods are exacerbated by his feelings for would-be actress Netta

Longdon, a denizen of the Earl’s Court neighborhood of London.

“You might say he wasn’t really ‘in love’ with her: he was ‘in hate’

with her. It was the same thing – just looking at his obsession

from the other side.” One version of George vows to win Netta’s

heart. The other is determined to kill her.The novel opens with a clinical definition of schizophrenia. Hamilton’s depiction of the disorder is surely one of the most remarkable in fiction. Every ‘click’ receives its own evocative description, as if George is experiencing the sensation for the first time. His brain feels “enclosed behind glass (like Crown jewels or Victorian wax fruit).” At other times it’s “as though the soundtrack in a talkie had mysteriously broken down,” or “as though ... scenes and activities were all taking place in the tank of an aquarium or even at the bottom of the ocean – a noiseless, intense, gliding, fishy world.” It makes sense, then, that George would be drawn to Netta, given that “her thoughts .. resembled those of a fish – something seen floating in a tank, brooding, self-absorbed, frigid.” Hamilton is equally meticulous in laying out Netta’s pathology. The chapter in which he focuses on her is extraordinary, delving into why “it was convenient for her to act this free-and-easy Earl’s Court life – irregular, unpunctual, self-consciously ‘broke,’ unconventional.” Hamilton claims that Netta possesses “a feeling for something which was abroad in the modern world ... something to do with blood, cruelty, and fascism.” The story climaxes on the night that German troops invade Poland, giving it additional intensity. Hangover Square’s structure is somewhat repetitive, and the book is shot through with a sense of foreboding that verges on oppressive. But Hamilton’s portrait of a man and a continent on the brink of insanity retains its power. Film aside: Hangover Square was adapted for the screen in 1945. Actor Laird Cregar would seem an ideal choice to play George Harvey Bone, but the plot was radically altered; George became a composer driven to kill when he hears loud noises. Cregar died soon after the film was completed. His friend and costar George Sanders believed the experience contributed to his death. The critic David Thomson calls the movie “a wretched travesty of Patrick Hamilton’s novel,” and notes that “Hangover Square – for all (director John) Brahm’s style, and Bernard Herrmann’s mad music – still waits to be filmed properly.”

DVDs

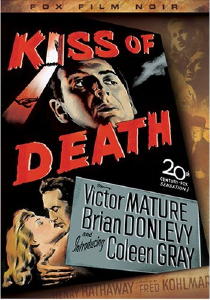

No one who has seen

Richard Widmark’s chattering psychopath Tommy Udo toss a woman in a

wheelchair down a flight of stairs in KISS

OF DEATH (1947) has ever forgotten it. The release of the

film on DVD will introduce an entirely new audience to this legendary

scene, which still packs a wallop. No one who has seen

Richard Widmark’s chattering psychopath Tommy Udo toss a woman in a

wheelchair down a flight of stairs in KISS

OF DEATH (1947) has ever forgotten it. The release of the

film on DVD will introduce an entirely new audience to this legendary

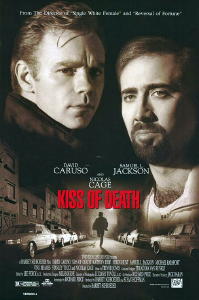

scene, which still packs a wallop.The movie, inspired by the experiences of New York district attorney Eleazar Lipsky, was an early look at the treatment of criminal informants. Low-level thief Victor Mature is forced by circumstance to play ball with D.A. Brian Donlevy. In order to put his past behind him, Mature testifies against the wild man Udo. When the system fails him, Mature must protect his family himself. Director Henry Hathaway, as in his other crime dramas CALL NORTHSIDE 777 and THE HOUSE ON 92ND STREET, films the action in documentary style. The script by Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer has dated – I doubt a hardened criminal would fall for Donlevy’s home and hearth shtick – and it includes voiceover by a woman who is not identified until twenty-two minutes in. But it digs deep into the issues presented by the use of informants as they play out on both sides of the law. Widmark’s Tommy Udo is as galvanizing a figure as he was six decades ago. When we first meet him he’s fantasizing about killing a cop, and things go downhill from there. Pushing words through his hyena’s grin, Udo is one of filmdom’s most loathsome villains. Considering the role was Widmark’s movie debut, it’s a wonder he ever worked again. Film Noir Reader editors Alain Silver and James Ursini are called on once more to provide a commentary track. I hear their voices around my place so often that I should start charging them rent. They do their customary fine job here, analyzing whether the film’s closing voiceover alters what we see in the final shots. The 1995 remake of KISS OF DEATH wasn’t accorded much respect when it was released. At the time, I found it a rock-solid piece of work. The DVD debut of the original prompted me to give it another look. The screenplay by urban novelist par excellence Richard Price (CLOCKERS, SAMARITAN) is an object lesson in updating material. His script retains the premise and structure of the Hecht/Lederer version while incorporating many sharply-observed contemporary elements. The district attorney is no longer an avuncular presence interested in the welfare of his informants, but a ruthless political operator (well played by Stanley Tucci) willing to sell out his own case for a judgeship. CSI: Miami’s David Caruso, in the Victor Mature role, exploits his position as a stool pigeon to settle personal scores. Mature’s line to the D.A. from the earlier film – “Your side of the fence is almost as dirty as mine” – seems more at home in this one.  The remake’s answer to

Tommy Udo is Little Junior Brown, a muscle-bound asthmatic given

genuine menace by Nicolas Cage. Little Junior is a

forward-thinking hoodlum who develops acronyms (or, as he says,

“akanyms”) to visualize his goals. He rejects one suggested by

Caruso because it’s “too negative.” Cage wisely doesn’t recreate

Widmark’s signature moment, but he does engage in acts of violence that

are almost as disturbing. Plus he bench presses an exotic dancer,

an impressive feat in its own right. The remake’s answer to

Tommy Udo is Little Junior Brown, a muscle-bound asthmatic given

genuine menace by Nicolas Cage. Little Junior is a

forward-thinking hoodlum who develops acronyms (or, as he says,

“akanyms”) to visualize his goals. He rejects one suggested by

Caruso because it’s “too negative.” Cage wisely doesn’t recreate

Widmark’s signature moment, but he does engage in acts of violence that

are almost as disturbing. Plus he bench presses an exotic dancer,

an impressive feat in its own right.Barbet Schroeder directs with a genuine feel for the lower middle-class neighborhoods of Queens, New York, and fills the frame with up-and-coming actors like Ving Rhames and Hope Davis. While the livewire presence of Widmark gives his scenes in the 1947 film an up-to-the-minute feel, the remake has the appealing, retro air of a throwback. Samuel L. Jackson’s character, a frosty New York cop with a perpetually weeping eye, wouldn’t be out of place in Donlevy’s office. The original KISS OF DEATH is an acknowledged noir classic, but the new edition more than holds it own. It’s one of the most underrated crime films of the 1990s. Note: Other installments of In the Frame can be found be going here. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME.

Copyright © 2006 by

Steve

Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

Return to

the Main Page.

|