|

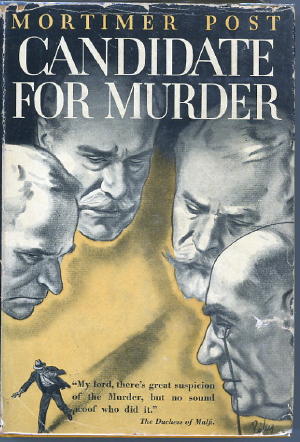

A DOLLAR WELL INVESTED: A NOTE ON MORTIMER POST, by Allen J. Hubin A couple of weeks I ago I went again to the annual Twin Cities Book Fair (at the state fairgrounds). Dozens of dealers from around the Midwest turn up at these events, and most of the books are pricey indeed. But I did run across a well worn first edition of Candidate for Murder by Mortimer Post for a dollar, probably the only book at this price at the fair, and I thought I might read it, so I made the big investment. (I’d owned a much nicer copy many years before, but it went with the sale of my collection in 1982.) Aside from the price, I'm not entirely sure what drew me to the book – certainly not its condition; more probably its Golden Age vintage. After purchase, I did a little checking to see what stature, if any, the book had in our field. But it seems generally to have been overlooked by the later commentators. No sign of it even in Barzun & Taylor, which is most surprising of all given the academic credentials of Candidate’s known author and its university setting. The book does seem relatively scarce. It never achieved an overseas edition nor a U.S. reprint, so the first edition was the only one published. A check of www.abebooks.com found seven copies offered from $25 to $100. My dollar seemed an even better bargain, but the bargain got better yet, as will be evident shortly. The publisher (Doubleday Crime Club, 1936) offers this useful blurb about the book (in part):  The celebrants at the

dinner dance given by Chatham University’s Faculty Club were horrified

at the discovery of the murdered bodies of Geoffrey Nye, Chairman of

the Political Science Department, and of Babette Whipple, his

niece. Those murders coming as they did a week after the suicide

of a foreign student, Carl Schacht, at the same club, threw the campus

into a turmoil of excitement, suspicion and fear. The celebrants at the

dinner dance given by Chatham University’s Faculty Club were horrified

at the discovery of the murdered bodies of Geoffrey Nye, Chairman of

the Political Science Department, and of Babette Whipple, his

niece. Those murders coming as they did a week after the suicide

of a foreign student, Carl Schacht, at the same club, threw the campus

into a turmoil of excitement, suspicion and fear.Four members of the university faculty, inseparable companions, constituted themselves unofficial detectives under the guidance of Lowell Gaylord, of the English Department. The three other members of the quartet were, respectively, professor-emeritus of Medicine, chairman of the Department of Biochemistry, and dean of the Law School. These four men because of their training and background inevitably approached the problem of murder from four different angles. But in the end it was the combination of these four different approaches that brought about the downfall of an intelligent and scientific killer. I’d read about three quarters of the book before some papers fell out of the back. One was a clipping of Isaac Anderson’s review of Candidate in the NY Times Book Review (12/27/36), another a handwritten note on a 3x5 card (apparently by one Fred J. Feldkamp) about the book, with another such (apparently by one D. E. Hobelman) on the reverse. But the real surprise was a typewritten piece, “Notes on CANDIDATE FOR MURDER by ‘Mortimer Post’,” signed (in type; no handwritten signature nor date) by Walter Blair. Blair has long been known as the author of this pseudonymous book, but I didn’t know of his collaborator. Read on: This novel was

written during 1934 and 1935 by me and another young faculty member of

the University of Chicago, and was published in 1936. I had

received my degree in English here in 1931 and I think that my

collaborator, Charles Kerby-Miller, still was working on his. I

was in the English department; Charles was teaching a College

Humanities course. My wife thought up the pseudonym: we were

charmed by the thought that the listing in a library catalogue – if the

book ever got into a library – would be Post, Mortimer.

Charles and I both were addicted to reading detective novels of all sorts – at the rate, probably, of three or four a week. Candidate was written in a combination of two modes that we admired. One was the ratiocinative or deductive, with hosts of interviews, clues, discussions and deductions, and with several murders at intervals which writers hoped would add to the confusion. The other mode was that Black Mask Magazine had exploited, the one which made Dashiell Hammett famous and which Erle Stanley Gardner was beginning to employ with great success: it was called “hard-boiled.” Our book contains what now seem frequent and terribly long questionings and analyses; but the point of view is objective, with no peerings whatever (as I recall) into the minds of the characters – a blasphemous bedding together, you might say, of Agatha Christie and Mickey Spillane. Charles and I talked over the characters and the plot, sometimes during telephone conversations (“Shall we kill so-and-so now or next week?”), sometimes to the accompaniment of a few drinks – of liquor as luck would have it, rather than bootleg poisons and abominations, since Prohibition recently had been discarded. Eventually we were able to agree what would go into each chapter; Charles would write outlines; I’d do a draft; then Charles would suggest revisions, and we’d fight over some of the suggestions. Now and then we’d have ferocious disagreements, cursing one another and pounding on tables or being heavily sarcastic. But we managed somehow to agree and even after it was all over to continue friends. I suppose that our chief startling discovery was that in writing a deductive detective novel, it was needful to concoct not one probable – well fairly probable – murder plot, but several, so that all but one can be eliminated by the chief amateur detective in working out his final solution. We decided to set out story against a background some of which we knew well, the University of Chicago. But we decided to disguise it by giving it a different name and a different kind of architecture, I can’t now remember exactly why. Those who knew the school in the 1930s will see that a number of aspects weren’t changed. The opening paragraph has “Our Alma Mater” played on chimes in a campus building in the evening: this was a nightly treat provided by chimes in Mandel Hall tower then. At a later point, there’s a Homecoming Game, a ritual actually performed in those days when football and fraternities and students with haircuts loomed larger than they do here now. The Scholars Club is arranged architecturally as the Quadrangle Club was in those days – even to the phone booths which have since disappeared. The activities staged there were typical of those quaint times, and we thought that the professorial badinage was like that of faculty members we knew. ‘Science’ plays a part in the story. We collaborators wandered over to the Billings Hospital research laboratories and had a colleague’s wife, Jessie Maclean, show us around a bit and tell us what was going on, so far as she knew in her capacity of secretary for somebody. This was the research that gave us our knowledge of scientists and their work. How we happened to hit upon the discovery that figures in the story I can’t recall, but we decided that it would be a bully thing to know about a connection between vitamins and hormones, and I don’t believe that scientists have made that important finding even today. I remember that in one laboratory we saw a complicated sculpture made of steel, tube and glass, and Jessie said that it was used to learn about hormones: we were impressed. When we had our hero visit the president’s office, we gave him an experience which we, as lowly underlings, never had had, so we had to invent details. We made something of a proliferating array of vice presidents who, people then feared, might soon outnumber the faculty: there were two of them! We also worked in Gaylord’s biography (p. 132), which we enjoyed compiling – especially the items which the president had kept off his shelves. As the authors asserted in p. vi, “All of the characters and scenes in this book are entirely fictional.” However, when the book appeared, faculty members around here and their spouses started to make completely wild guesses about prototypes for the characters. Since it was rumored that Martha Dodd, the daughter of a professor of history, had the unconventional habit of calling informally on young bachelors late at night, gossipers decided that Babette Whipple was a representation of her. (Subsequently Martha Dodd had adventures that even the most imaginative fiction writer would never have been able to originate in the 1930s.) Since Mrs. Charles Read Baskerville, an English professor’s wife, had a wicked tongue and dry wit, and since the authors greatly admired her, the portrait of Mrs. Martha McDermott was said to resemble her. A maid named Aldona worked a day each week for several English Department wives, and some of her remarks allegedly were recorded. Gossipers compared Lens Penga with Professor Anton Carlson, and Penga did look like him; but the writers had only the sketchiest acquaintance with the great Carlson. Geoffrey Nye was said to resemble one – or more – of the men on the quadrangles who, rumor said, thought highly of Nazi Germany. Lowell Gaylord was likened to John Mathews Manly, not his appearance but his character. But my wife claimed that I gave that heroic character all of my bad habits and then obviously admired Gaylord for having them. It is true that I punned at times. Gaylord committed fewer puns in the book, however, than he did in the original draft because Charles – probably with reason – claimed that no decent man punned all that often. The authors made Gaylord a specialist in Elizabethan drama, I believe, because they’d found a great many appropriate quotations about murder and such in Elizabethan plays, and they liked to have Gaylord toss them off at appropriate – or inappropriate – times. The original title for the book, Great Suspicion, was taken from one of those quotations – the epigraph. Naturally the publisher thought up a better one. The chief other change an editor made was to change a detective’s name from Litmus to Litmar. The authors probably wanted to work in every bit of science they’d picked up, and they may have thought this name was funny. One bit of fun they had was this: they distributed with lavish hand names of friends, using them for buildings, streets, halls in Chatham College, and characters not at all like them. Our friends were happy to be helpful, and never objected. Which finishes the piece. I don't know that this account was ever published anywhere ... it would be interesting to know if this is its first public airing. About Charles (William) Kerby-Miller I could find out little. He received a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1938, and was noted as a Wellesley College scholar and author/editor of a couple of scholarly books. No birth or death year could be identified for certain in my searches, but I rather suspect he was the Charles Kerbymiller (given thus) in the Social Security Death Benefits records with dates of 1903-1971. Walter Blair (1900-1992) has an entry in Contemporary Authors which lists his numerous publications but makes no mention of his collaborative mystery. Blair was a graduate of Yale and recipient of a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1931. He was successively instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, professor, and professor emeritus of English at that University for some 63 years. It's a little surprising that, given the authors’ fondness for detective fiction, neither tried the form again. Unless, of course, any such tries are buried under unidentified pseudonyms... Regarding some of the other people mentioned in Blair’s notes, Martha Dodd (1908-1990) certainly did experience adventures and achieve a reputation, not all of it particularly good. Much detail can be found at www.traces.org/marthadodd.html, which particularly concentrates on her time in Germany in the 1930s while her father was U.S. ambassador there. Anton J. Carlson was born in Sweden in 1875 and died in 1956. He was a physiology professor at the University of Chicago and president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Dr. Carlson was the first recipient of the Humanist of the Year award from the American Humanist Association in 1953. John Mathews Manly (1865-1940) was a graduate of Furman University and became chair of the English Department at the University of Chicago. Finally, I wonder how the “Notes” by Walter Blair and the other papers came to rest in this particular copy of Candidate. Could there be a clue in the statement that the authors used the names of friends for buildings, and that the first sentence of the book mentions the chimes ringing from Hobelman Tower? You will recall that a D. E. Hobelman penned one of the notes I found on a 3x5 card in the book. And I learned that one Fred Feldkamp (1914-1981) was friend and literary executor to humorist/journalist Will Cuppy, a University of Chicago graduate, and that Cuppy used to make notes for his articles and books on 3x5 cards. Maybe there’s more of a story here somewhere than appears on the surface! Acknowledgment: Thanks to bookseller Dan Adams of Waverly Books, ABAA, www.waverlybooks.com for providing the photo of the dust jacket cover. _____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. stevelewis62 (at) cox.net

Copyright © 2005 by Steve

Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

Return to

the Main Page.

|