|

FORGOTTEN WRITERS #3: ROBERT MARTIN, by

Bill Pronzini

As with any

large group, professional writers come in all sizes, shapes, races,

creeds, colors, attitudes, dispositions, and personalities. Some

are eccentrics, like Jay Flynn. Some are breast-beaters, literary

narcissists. Some are just plain fundaments (to use the polite

term). Most are pretty good folks, generally. And a few – a

very few – are intrinsically, unassumingly nice people: the kind, if

you could pick and choose, you might want as a close friend, a spouse,

a parent or grandparent.

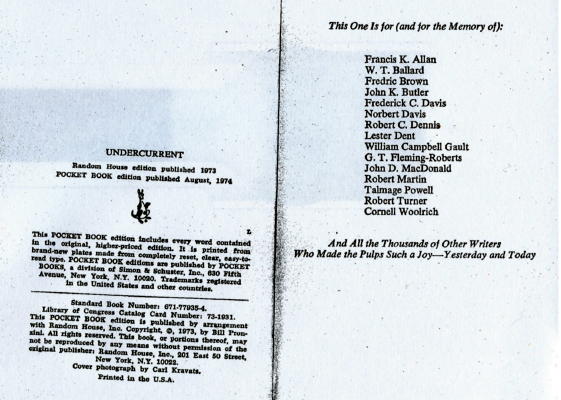

Robert Lee Martin was one of that last, small category. A genuinely nice man who deserved a hell of a lot better than he got out of this life. You can’t always tell from reading a writer’s fiction what sort of person he or she is, but in some instances you can be fairly sure. I was sure about Bob long before I had any personal contact with him. All of his fictional series heroes – private eyes Jim Bennett and Lee Fiske, and Doctor Clinton Shannon (nee Clinton Colby in early pulp stories) – aren’t just good guys, they’re nice guys. Problems, yes. Quirks and foibles, yes. Lapses in taste and judgment and morality, yes. They wouldn’t be real and you wouldn’t care what happens to them, otherwise. But underneath, at the core of their humanity – nice guys, by God. A Midwesterner, born in 1910, Bob lived most of his life in the Cleveland area. He was a personnel manager by profession, with an industrial manufacturing company, and did pretty well at it – well enough to support a wife and three children in relative comfort. He was an avid reader (Chandler, Hammett, James M. Cain, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Maugham, Fitzgerald), and in the late thirties he decided to try his hand at stories for the pulp magazines. It wasn’t long before he was selling steadily to Popular Publications: throughout the forties and into the early fifties his name was cover-featured on Dime Detective, where the bulk of his stories appeared, as well as on such other magazines as Black Mask, Detective Tales, New Detective, All-Story Detective, and 15-Story Detective. An occasional Popular reject appeared in Thrilling Detective and Mammoth Detective, among others. Most of his Dime Detective novelettes and novellas feature Jim Bennett, head of the Cleveland office of the New York-based American (later American-International) Detective Agency. In one sense the Bennett stories are typical pulp fare, in that they contain plenty of rough-and-tumble action; but in another sense they’re unusual because they also place strong emphasis on detection and character, particularly that of Bennett himself. In an era when first-person private eyes were often little more than boozing, wenching, wise-cracking ciphers, Bennett comes off as a real and intelligent human being: a man tough when he has to be, yet gentle, likable, and vulnerable. The same is true of Lee Fiske and Clinton Colby/Shannon, though to a somewhat lesser degree: neither is as sharply delineated as Bennett. A few other protagonists made a pulp appearance now and then – a PI named Deegan, an insurance dick called Regent – but for the most part Bob left his fictional detecting up to Bennett, Fiske and Doctor Clint. He also preferred rural and small-town settings to an urban one: many more of his stories are laid in villages, on farms and ranches in the vicinity of Cleveland and other parts of northern Ohio than in Cleveland itself. When the pulp markets began to decline in the early fifties, Bob turned to novels. And like Chandler and numerous others, yours truly included, he also turned to the cannibalizing of his own short stories – almost exclusively, those published in Dime Detective – for the plots of those novels, with varying degrees of success. His first book, Dark Dream (Dodd, Mead, 1951) is an interesting but flawed blend of two Jim Bennett novelettes: “Death Under Par” (Dime Detective, May 1947) and “Death Gives a Permanent Wave” (DD, October 1947). The Little Sister (Gold Medal, 1952) – the first of seven titles to appear under Bob’s pseudonym of Lee Roberts – features Lee Fiske and is an effective expansion of “Pardon My Poison” (DD, April 1948). The second Bennett, Sleep, My Love (Dodd, 1953), is another and better fusion of two novelettes: “Case of the Careless Caress” (DD, January 1948), which features Lee Fiske rather than Bennett, and “I’ll Be Killing You” (DD, February 1950). Several other Bennett novels also have their origins in the pulps, including three of the best in the series: Tears for the Bride (Dodd, 1954), in which Bennett becomes enmeshed in a shooting and other intrigue on a cattle ranch owned by the parents of his secretary and love interest, Sandy Hollis (“Killers Can’t Be Careless,” DD, November 1946); To Have and To Kill (Dodd, 1960), about murder among a wedding party on a fancy Lake Erie estate (“A Shroud for Her Trousseau,” DD, June 1949); and A Coffin for Two (Hale, 1964), about odd doings connected with a family burial vault in a small town (“Death Under Glass,” DD, February 1952. another Lee Fiske vehicle). Between 1951 and 1960, Bob published ten Bennett novels with Dodd, Mead (two of which were the bases for episodes of the TV series 77 Sunset Strip and Surfside Six); a second Fiske, as by Roberts, also with Dodd: two Clinton Shannons, one Dodd and one Gold Medal; and three nonseries suspense novels, two as by Roberts and all with Dodd. The best of the non-series books, and one of his best overall, is Judas Journey (1956), as by Roberts. It’s atypical of Bob’s work for three reasons: first; because the setting is Texas and Mexico; second, because the protagonist, oilfield worker Rackwell Ramsey, is not a nice guy, is in fact something of a heel almost to the very end; and third, because it contains a surprising amount – by the standards of the hardcover mystery in 1956 – of fairly steamy sex. In all of Jim Bennett’s cases, he never once gets laid, not even by Sandy Hollis! Bob was an uneven writer, as so many of us are. Some of his plots work nicely; others clunk along with uneven pacing and not much cohesion. On the plus side: His characters are all believable people; he had a nice, low-key style; his descriptions and sense-of-place are generally excellent; his scenes of violence are almost always understated and told with distaste for the mangling of human flesh. On the debit side: He sometimes had his heroes and other characters act with motivation that is weak and illogical; his dialogue, while usually good, now and then fails to ring true (and in a couple of instances is downright bad); and he had a habit of not tying off some rather large loose ends. But above all he was – and still is – readable, in the best sense of that term. He was never guilty of what John D. MacDonald once referred to as the “Look-Ma-I’m-Writing!” syndrome. If the fifties was a highly successful decade for Bob, the sixties was the exact opposite – a hideous decade in all respects. The company for which he worked was gobbled up by International Telephone and Telegraph, and Bob eventually resigned when he found that he couldn’t function under the conglomerate yoke. His wife fell ill – a long, painful, and financially draining illness that culminated in her death in June of 1970. And for reasons that had to do with declining sales and a changing market for mystery novels, neither Dodd, Mead nor any other American publisher wanted Bob’s work between 1961 and 1971. His last four published novels – three Bennetts: A Coffin for Two, She, Me and Murder, and Bargain for Death; and one Clinton Shannon, Suspicion, as by Lee Roberts – found homes only in England in the early sixties and were not brought out here until the short-lived paperback house, Curtis Books, did them in 1971 and 1972. Bob more or less quit writing in 1963, as a result of all the personal and professional disasters. When I began corresponding with him in 1972, he was working on his first novel in nearly ten years. He lived alone then, in an apartment in Tiffin, Ohio, and relied for his livelihood on a small pension, some scattered royalties and foreign rights checks, and the help of his family. I initiated the contact between us. In those days I corresponded with a number of writers whose work I had admired over the years: Evan Hunter, Jim McKimmey, Talmage Powell, others. I was living in West Germany, and the more mail from home, the less far-away-from-it-all I felt. I had read Bob’s pulp stories in the sixties, when I first began collecting pulps, and enjoyed them, but what made me determined to write to him was a copy of the Curtis Books edition of Bargain for Death that I found while on a business trip to New York that spring. His response was immediate. He was flattered, he said, to hear from a fellow mystery writer who remembered and admired his work. He’d had precious little contact with writers since his Dodd, Mead days, with two exceptions. One was a fellow pulpster, Cyril Plunkett, who had lived and recently died in Toledo. The other was John D. MacDonald, whom he had known ever since they shared an agent – Joseph T. “Cap” Shaw, of Black Mask fame – during their pulp-writing days in the late forties. Bob spoke highly of John D., both as a writer and a person. In a 1975 letter, Bob wrote that he had been “smack in the middle” of a hassle between John and newspaper columnist and bestselling writer Jim Bishop the previous year. It seems Bishop implied in a column that he had “discovered” John when he, Bishop, was an editor at Fawcett Gold Medal in 1949, by persuading the late Bill Engle to publish The Brass Cupcake. Bob sent the column to MacDonald, whose reply was that Bishop “must have fallen out of his tree or something” and had “disinterred Bill, skinned him and was wearing his skin,” for Bishop had had nothing to do with the purchase of The Brass Cupcake. Bob received permission to send John’s letter to Bishop, who wrote back giving names, dates and other pertinent facts about his editorial duties at Gold Medal (which MacDonald again disputed) and in the bargain indulged in the most arrogant sort of literary snobbism: “There is no credit in ‘discovering’ a John MacDonald. His books are successful and make money, but I would prefer to have discovered a Thomas Wolfe or even an Irwin Shaw...” Bob and I exchanged several letters in 1972. I was then working on the third “Nameless” novel, Undercurrent, and I wrote him of my intention to dedicate the book to him, John D., and several other writers whose pulp fiction I particularly enjoyed. (Which in fact I did.) His response was typical of the man: “I am honored and flattered that you have included me in the dedication of the Random House novel. It is one of the nicest things that ever happened to me, and the very first time I have been mentioned in a book dedication... I am sending a copy [of your letter] to my agent, who will be as pleased as I am. I certainly do want a copy of the book – but autographed – when it comes out.” We fell out of touch before Undercurrent was published (although I eventually did see to it that he received an inscribed copy). It was my fault; I had decided to move back to this country in 1973 and was so busy making preparations and trying to finish a couple of novel projects that I let more than one correspondence lapse. As a result it was more than two years before Bob and I began to regularly exchange letters again. He reestablished contact in September of 1975. And his four-page letter was not a happy one. From the fall of ’74 to the spring of ’75 he had been seriously ill and partially disabled with a spinal arthritic condition. Since recovering, he had spent some pleasant days in Texas with his son and the son’s family, and with his brother, a doctor and former coroner who lived on Lake Erie, but for the most part, he said, “There are so few people I see or talk to. My children have their own lives and families, which is as it should be, but I am lonely much of the time.” His attempt at a career comeback had been unsuccessful. The novel he had been writing in 1972, a non-series mystery called A Time of Evil, had not sold; neither had a Jim Bennett, A Friend of the Family, he’d written the previous year. An editor at Pinnacle had jerked him around on Friend for months, promising to buy it as soon as he could find a slot, only to eventually return the manuscript with the excuse that he was still over-inventoried – a bitter disappointment to Bob. He lamented to me that he had begun to wonder if he had been out of touch with the markets for too long, or if perhaps the problem was his agent, who had been swallowed up by a large, high-powered outfit that specialized in film deals as well as book sales. He was “beginning to have the feeling that I am in another ITT situation ... a tiny frog in a mighty big puddle.” He asked if I could recommend a small agent who might be willing to work with him. “I am good for at least two or three mystery and detective novels a year,” he wrote, “60,000 to 80,000 words each... Writing is not just a hobby with me; after I left ITT I counted on writing income to supplement my small pension benefits. And I truly feel that the last two books are as good as any I’ve written.” I gave Bob a name – not a good one, dammit, though at the time I thought this agent was among the best – and he wrote the person asking for representation. He was turned down. But he remained as optimistic as always; he had a burning desire to get back into print and believed tbat sooner or later be would sell a new book. I believed it too. Early in 1976 I offered to read the two unpublished manuscripts, to maybe offer some marketing advice. I don’t know if Bob would have taken me up on my offer. I don’t know if his manuscripts might have sold with the right agent handling them; I only know that they didn’t sell and now never will. Bob Martin died before he could answer my letter. When I didn’t hear from him within a few weeks – he was almost always prompt with his replies, even if I wasn’t with mine – I began to worry that something was wrong. I was about to write again when I received a letter from his son in Texas, with the news that Bob had passed away. The son was letting me know because Bob had spoken fondly of me, and because he (the son) had found my last letter among Bob’s papers.  I never met Bob Martin

face to face; I have never

even seen a photograph of him. And yet, the news of his

death moved me close to tears. To this day I’m not quite

sure why. A combination of things, I guess: the fact that he was

a nice man, a man I wish I had met and known better and perhaps helped

in some small meaningful way; the fact that he had so much tragedy and

adversity in his life; the fact that those last two novels of his never

sold, and would never sell, and he wanted so desperately to be a

published writer again. And those two haunting sentences in his

1975 letter: “There are so few people I see or talk to. My

children have their own lives and families, which is as it should be,

but I am lonely much of the time.” I never met Bob Martin

face to face; I have never

even seen a photograph of him. And yet, the news of his

death moved me close to tears. To this day I’m not quite

sure why. A combination of things, I guess: the fact that he was

a nice man, a man I wish I had met and known better and perhaps helped

in some small meaningful way; the fact that he had so much tragedy and

adversity in his life; the fact that those last two novels of his never

sold, and would never sell, and he wanted so desperately to be a

published writer again. And those two haunting sentences in his

1975 letter: “There are so few people I see or talk to. My

children have their own lives and families, which is as it should be,

but I am lonely much of the time.”To close that same ’75 letter, he wrote: “One of the few Spanish phrases I know is, ‘Adios, amigo,’ which I thought meant simply, ‘Goodbye, friend,’ but in Texas I learned that the true translation is ‘Go with God, my friend.’ And so ... adios, amigo.” Adios, amigo, I thought that day in 1976. At least you’re not lonely anymore. This article first appeared in Mystery Scene #14. Copyright © 1988 by Bill Pronzini. A companion piece, another tribute to Robert Martin by fellow Tiffin OH resident Jim Felton, can be found here. A complete bibliography is here, and reviews by Gary Warren Niebuhr of most of the Jim Bennett private eye novels are located here.

MORE COVERS:

YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. |