|

A

‘Rhode’ by any other name,

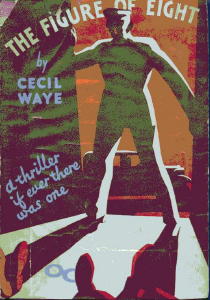

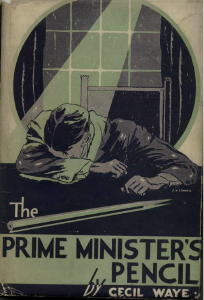

by Tony Medawar John Street – former intelligence officer, practitioner of politico-military propaganda and well known to readers of crime and detective stories as ‘John Rhode’ and ‘Miles Burton’ – was “not an easy man to know – his reticences were such that all who met him could not fail to respect them, but to those who were privileged to enjoy his friendship he leaves memories of kindnesses and sensitive understanding that might surprise many of his readers.” FOOTNOTE 1. Something that came as a surprise for almost all of Street’s many readers when this article first appeared is that he also wrote mysteries under another, previously unsuspected pseudonym. A pseudonym that, like ‘John Rhode,’ plays on his real name. John Street was also ‘Cecil Waye’, author of a series of four novels published in the early 1930s. FOOTNOTES 2 and 3. The main character in the series is “London’s most famous private detective,” Christopher Perrin. Perrin and his sister Vivienne – Vi to her brother – constitute ‘Perrins, Private Investigators’, a firm of private investigators established by their late uncle. FOOTNOTE 4. Perrins is “situated on an upper floor in Hanover Square. You entered a doorway and mounted a couple of flights of stairs before you came to a brass plate with the name of the firm engraved upon it. The offices themselves consisted of two large outer rooms, one for the use of the staff, and the other arranged as a wonderfully complete reference library. Besides, there was a comfortable waiting-room, and an inner sanctum, into which only specially favoured clients were admitted.” There is only one member of staff, Miss Avery, Perrins’ efficient young secretary who seems to spend most of her time “surrounded by a sea of newspapers, which she was busily scanning, stopping every now and then to snip out a paragraph and lay the cutting in a tray by her side.” The inner sanctum is a small room within which “the most conspicuous thing ... was the bright fire blazing in the grate, to which were drawn up three or four luxurious armchairs.” Perrin has much in common with Albert Campion and other ‘posh’ detectives of the time. He drives a “luxurious motor.” He is “brilliantly clever,” “an athletic-looking man . . . with curiously penetrating eyes.” And he is “tall and straight, with an eager, almost boyish face” and “a disarming smile.” As a detective he has extraordinary skill in disguise and is adept at adopting different accents. As for Vivienne, she is – at least in the eyes of the man who will go on to become her husband – “the most dazzling pretty girl he had ever seen.” But, quite against expectations, it is Vivienne who solves the murders in Murder at Monk’s Barn, the first of the four ‘Waye’ mysteries. She meets her future husband in this novel and, by the time of the second novel, she has retired from the firm and moved out of the flat in Shillingstone Mansions, South Kensington, which she and Christopher had shared, together with their all-purpose maid, the redoubtable Mrs Clutterby. After Vivienne’s marriage, Christopher takes “a very comfortable suite of rooms in Buckingham Gate” which, up until his own marriage later in the series he shares with David Meade – “a young man, tall and beautifully dressed, with a melancholy expression relieved by a certain humorous twinkle about the eyes.” FOOTNOTE 5. Meade joins the firm as an assistant shortly after Vivienne’s departure and is a full partner by the time of the events chronicled in the last of the ‘Waye’ novels. Meade and Perrin are good friends and play squash together when the opportunity arises – “Christopher prided himself that David looked less like a private detective than anyone else whom he could have chosen. In addition to this most useful qualification he possessed a quick brain and a large fund of common sense.” As with other notable male detective duos there appears, at least to today’s readers, a definite subtext to this, emphatically so when Perrin’s misogynistic attitudes eventually emerge: “With the exception of his sister, Vivienne, Perrin, throughout his professional career, had always avoided women as far as possible. Detection, he had said more than once, depended upon logical deduction, and once the female element came in at the door, logic flew out of the window. If a man performed a certain act one could usually deduce his motives for doing so. But when a woman performed a precisely similar act, it was impossible to guess the motive that had urged her too it. She probably didn’t know herself.” Meade however has no such reservations about women and, when alone in the office with Miss Avery, the two “were on considerably less formal terms than appeared publicly,” with Perrins’ secretary “swinging her legs impudently” and ready to accept any invitation to spend “the evening on the razzle.” The four ‘Waye’ titles – Murder at Monk’s Barn, The Figure of Eight, The End of the Chase and, probably the best known of the four, The Prime Minister’s Pencil – were published in the early 1930s and, like other books of that period, are extremely elusive. FOOTNOTE 6. For that reason, it does not seem unreasonable to describe them in some detail.

Murder at

Monk’s Barn

Burden sends Cartwright for the village doctor, Doctor Palmer, and himself goes up to Wynter’s dressing-room where “lying in a huddled heap in front of the dressing-table was the form of man half-dressed, a woman on her knees, vainly endeavouring to staunch the flow with a pocket handkerchief.” Wynter is dead, “a bullet wound in the centre of his forehead ... the heavy curtains were closely drawn, but in one of them was a neat round hole ... the bullet had clearly come from outside, and the shot which he had heard had been fired from the garden.” When Burden searches the garden, he quickly finds the weapon, “a double-barrelled gun,” which proves to have belonged to the murdered man. So far so good but, as the curtains were closed, how could the murderer have known Wynter’s position within the dressing room and where to aim? And how could he – or she – have escaped from the garden quickly and unseen? If, that is, Wynter was shot by the bullet that made the hole in the window. It is in effect an impossible crime and baffles Burden and his senior officer, Superintendent Swayne, described later as “a very good fellow, but the workings of his mind are a trifle transparent.” Despairing at the lack of progress by the official police, Austin Wynter – the dead man’s younger brother and partner – calls on Perrins: “I don’t believe the police will ever find out who killed him and I want you to try. Expense is no object; I would spend every penny I possess to see whoever it was tried and convicted.” There are plenty of suspects, including Dr Palmer and Mrs Hewitt, the vicar’s wife, who had been in Monk’s Barn earlier on the day that Wynter died. And then there are those closest to the dead man: the maid, Phyllis: Wynter’s wife Anne, whom Austin dislikes; Frank Cartwright and his wife Ursula; and old Croyle, the Wynters’ gardener who had been laid off from Wynter & Son after an industrial accident. The prime suspect however would seem to be Phyllis Mintern’s father Walter, “a thoroughly bad character,” whose fingerprints were found on the gun. There is a motive as Mintern had been the Wynters’ second gardener for five years but had recently been sacked by Gilbert Wynter. Nevertheless, and despite the ‘evidence’ of the fingerprints, Austin is certain that Mintern is innocent – “a rough uneducated man, with a violent temper, I admit. But he had plenty of native cunning, and I feel sure that he would never have left such an obvious clue as the gun behind him.” And what about Austin himself, charming and convincing, but he undoubtedly benefited from his brother’s demise. Vivienne has her doubts – “she liked him, felt instinctively that he could not be his brother’s murderer. Her instinct told her that he was telling the truth. And yet ...” The Perrins decide to take on the investigation and, as Christopher is tied up with a case in Medhampton, Vivienne departs for Fordington alone – “I’m not going to announce myself as the official representative of the firm. I shall be Miss Perrin, an art student studying the picturesque features of out-of-the-way corners of England.” On arriving at Fordington, Vivienne lodges with the garrulous Mrs Marsh who, in addition to being a first class gossip, “combined the duties of postmistress and keeper of the general shop.” Mrs Marsh provides an excellent introduction to the people and particulars of the village. She is well aware of the rumours of Mintern’s impending arrest but like Austin Wynter, she doubts the police have the right man in their sights, not least because she knows for a fact that Mintern was poaching on the night of the murder. Mrs Marsh has a different suspect in mind, the dead man’s widow, Anne Wynter. In her artist guise, Vivienne is able to inveigle herself into the Cartwrights’ home, White Lodge, and Ursula Cartwright takes her on a tour of the property and shows her a rarely used lumber room whose window looks directly across at Monk’s Barn. Perhaps ... but, no, Vivienne cannot conceive of a theory that would fit the facts – “No man could make a bullet travel in a semicircle and enter by the other window. And what about the gun? Could Mr Cartwright, having fired the shot, have hurled it into the shrubbery from the lumber-room window? Most certainly he could not, such a feat would be impossible.” Investigating the personalities of the victim and other people in the village Vivienne uncovers an illicit relationship between Gilbert Wynter and one of the suspects and some hitherto unsuspected motives. And she herself falls in love, which calls into question her ability to carry out an objective investigation as the subject of her affection is high on the police’s latest list of plausible suspects. She returns to London and, as “Perrins had a hard and fast rule that, wherever possible, their investigators were to work hand in glove with the police,” Christopher decides that the time has come to call on Superintendent Swayne at Yatebury. FOOTNOTE 10. The Superintendent is impressed but surprises Christopher by disclosing a second, equally hidden relationship in the village, one that seems to identify a new prime suspect. Then there is a shocking development; a second murder in Monk’s Barn – “a fortnight, almost to the hour, since Gilbert Wynter had fallen with a crash above, a bullet through his head.” The sequel leads to an arrest and then Vivienne makes a chance discovery in the garden of Monk’s Barn, which points to an incredible solution of the mystery, but before the novel ends there will be a further death in Fordington. The Figure of Eight

Notwithstanding the involvement of the mysterious and untraced ‘foreigner,’ there is no evidence of foul play. On the contrary, “the evidence of Dr Ruthven, supported by that of the house physician, although veiled in technicalities, could be interpreted in no other way than as death from natural causes. The jury delivered a verdict in accordance with this evidence, and there – so far as the provisions of the law were concerned – the matter ended. A few brief paragraphs appeared under such headlines as ‘Coroner’s strictures at West London inquest’; ‘Strange death of a Montedorian subject’, and that was all.” At least it would have been all had not the name of Dr Ruthven caught the eye of Christopher Perrin, now the sole partner in Perrins, Investigators and now routinely described as “Perrin” (rather than ‘Christopher’ as in Murder at Monk’s Barn). Ruthven’s son has for many years been one of Perrin’s most intimate friends and the doctor is well known to the detective. Perrin’s interest is also stimulated by the fact that the dead woman was a Montedorian and therefore constitutes a link, however vague, to a dispute of international importance. Then, by an extraordinary coincidence – a development not unknown in detective fiction – the next person to call on Perrins is Señor Vincente de Lanate, Chancellor of the Montedorian Legation in London. Lola Martinaes was his mistress and Señor Vincente is quite certain she was murdered – “People die that way in Montedoro, sometimes” and certain valuable documents have gone missing from her flat. Señor Vincente asks Perrin to trace the mysterious man with whom Lola spent at least part of her last evening, a commission that, with certain conditions, Perrin accepts. His first act is to contact an old friend, Detective Inspector Philpott of Scotland Yard, who in the words of the Assistant Commissioner, “combined the ability to see, as far as the rest of us, through a brick wall, with the tenacity of a bulldog.” However, no sooner have Perrin and Philpott discussed the case than there is a very startling development. There are more deaths and the circumstances suggest to Perrin that these must have been murder and linked to the dispute between Montedoro and San Benito. The mystery assumes an ever-higher profile, so much so that there is Government concern that the deaths “may become the pretext for a war between Montedoro and San Benito, and if that happens, America and most of Europe may be drawn in too.” The Home Secretary presses Scotland Yard to clear up the case quickly. The stakes then are high but there are further baffling developments and disappearances and, before too long, Christopher Perrin and David Meade find themselves playing for the highest stake of all – their lives. The End of the Chase

On returning to London he finds that Perrins has a new case. Lord Newbury, an international financier whose name alone was “in financial circles ... a guarantee of good faith.” Newbury is a man “on particularly good terms with the Prime Minister of the day, who was an honest politician, if such a phenomenon can be imagined to exist.” The peer has a valuable secret, which, though it will be some time before all of the links in the chain are clear, is the key to the Ostend riddle. And before the secret is revealed two people will die and Christopher Perrin will again find his life in danger. The review of The End of the Chase in The Times Literary Supplement praised ‘Waye’ as having “a shrewd eye for the essential weaknesses and fears of human beings” and Perrin for his “clever handling of dangerous situations.” FOOTNOTES 13 and 14. The

Prime Minister’s Pencil

And Perrin is particularly troubled by Sir Ethelred’s callous concern that political opponents might use Solway’s death to discredit him. While the detectives ruminate, Dr Martlock performs a post mortem and reaches the surprising conclusion that Solway died of trypanosomosis, which a specialist in parasitic diseases later confirms. Perrin, however, is far from satisfied – “how, in heaven’s name, did a man whom we are told never spent a night away from the majestic portals of Oldwick Manor, acquire sleeping sickness, which is unknown outside the tropics?” But Perrin’s rather casual pursuit of this riddle soon leads to a brutal death for one in his circle. T hen there is an astounding development and, arguably, one of the most sensational murders in any detective novel of the Golden Age. A reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement considered The Prime Minister’s Pencil “a good example of detective fiction” but criticised what it considered too early and prominent a clue to the solution of the main mystery. FOOTNOTE 15. These then are the novels of ‘Cecil Waye,’ and they prompt a question. Why did John Street decide that they should appear under a further pseudonym, distancing them from the bulk of his detective fiction? The four books are broadly similar in style to the mysteries of ‘John Rhode’ and ‘Miles Burton’, and, with one significant exception, their plots do not contain any excessively implausible elements. It is of course impossible to know Street’s reasons but some points do seem worth noting. First, certain key elements of the plot of The Prime Minister’s Pencil echo very strongly some of those in The Figure of Eight and The End of the Chase. Secondly, one of the novels – The End of the Chase – concerns Hungarian politics, a subject on which Major C. J. C. Street was already recognised as an authority and this would seem reason enough to have used a pseudonym at least for that particular title. The Figure of Eight is rather derivative with distinct echoes of the mysteries of Sax Rohmer and Anthony Hope’s Ruritania. And, finally, someone with Street’s military and scientific expertise and connections would have known that the technical details of The Prime Minister’s Pencil were somewhat shaky even if the full potential of the means of murder concerned was then very far from being as widely understood as it is now. Whatever the explanation for the use of the additional pseudonym and the decision to abandon it after only four titles, John Street had a strong sense of humour and he certainly enjoyed the art and science of deception in all its forms. Perhaps that alone was motive enough to pose as ‘Cecil Waye.’ Whatever the truth, it is hoped that the many people who enjoy his ingenious and entertaining mysteries will be pleased to learn of this, Street’s final secret and that there are four more titles to trace even if, initially, they may be more than a little frustrated by their general scarcity. To quote Ian H. Godden, an admirer of Street’s work, “Good hunting.” FOOTNOTE 16. Footnotes: 1. Letter from “E. C.”, The Times, 2 January 1965. “E. C.” might be Edmund Crispin. 2. It will be asked – quite reasonably – how this is known. The sales records of one of John Street’s agents, Aitken & Stone, detail all of the novels published under his ‘John Rhode’ pseudonym and also include four unfamiliar titles. Examination of the British Library catalogue showed that these titles were published as by ‘Cecil Waye,’ and examination of the text confirmed that Street was the author. As with ‘John Rhode’ the pseudonym is of course a phonetic pun on Street’s own name – Cecil John Charles Street. Incidentally, as ‘Miles Burton’ Street’s agent was A. M. Heath & Co. 3. Once again, I am indebted to Brian Stone, formerly of Aitken & Stone, on this occasion for allowing access to John Street’s sales records. I am also indebted to Donald Rudd. 4. By The Prime Minister’s Pencil the firm has become simply Perrins, Investigators. 5. Christopher first meets his future spouse in circumstances similar to those in which Vivienne first met hers. His marriage takes place shortly after The End of the Chase. 6. The Prime Minister’s Pencil is the only ‘Waye’ title to be included in the uneven A Catalogue of Crime [1971] by Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor who, while criticising the pace and characterisation, noted that “a word of praise is due the lucidity and reasonableness of several early discussions of the data. [The novel was] not a success but a good try.” 7. I am indebted to Nigel Williams for providing digital versions of the original artwork by Eugene Hastain for the cover of this book and The End of the Chase. The original artwork is available from Nigel Williams Rare Books, 22 & 25 Cecil Court, Charing Cross Road, London, WC2N 4HE, Telephone 020 7836 7757, Fax 020 7379 5918. Website: www.nigelwilliams.com, email: queries @ nigelwilliams.com. The white mark in the middle of the picture is the reflection of the flash used to take the photograph. The other photographs are taken from jackets of the American editions. 8. The entry for the “mystery author” ‘Miles Burton’ in Who’s Who in Literature [1934] gives “tides and black magic” as the author’s ‘special subjects.’ No special subjects are given in the entry for ‘John Rhode’ who, unlike ‘Burton’ does not have an entry in any later volumes. 9. Times Literary Supplement, 11 June 1931. 10. “As a result, the firm was in much greater favour with the Yard than any other private agency. Indeed, the highest officers of the CID were not above consulting Perrins on occasion, strictly unofficially, of course.” Perrins would appear to be very well-known among police circles and not only in Scotland Yard – in Murder at Monk’s Barn, Superintendent Swayne comments that he has “heard of Perrins often enough.” By the time of The End of the Chase Christopher Perrin’s fame is such that he is described by one criminal, entirely without irony, as “the most dangerous person in Europe.” 11. Times Literary Supplement, 25 February 1932. 12. There may be autobiographical relevance in some of the novel’s commentary on Hungarian mores. 13. Times Literary Supplement, 8 September 1932. 14. Ibid. 15. Times Literary Supplement, 13 April 1933. 16. “Why kill for a reading copy? The quest for Rhode and Burton” by Ian H. Godden, CADS 30, March 1997. The ‘Cecil Waye’ novels of C. J. C. Street: Murder at Monk’s Barn.

London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1931; 314 pages.

The Figure of Eight. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1931; 320 pages. The End of the Chase. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1932; 319 pages. The Prime Minister’s Pencil. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1933; 318 pages. British publication details only. The Figure of Eight and The Prime Minister’s Pencil were published in the USA by Kinsey in 1933. No US publication details have yet been traced for the other two ‘Waye’ titles. Note: This slightly revised article originally appeared in CADS #44 (October 2003). CADS is a British mystery fanzine published irregularly by Geoff Bradley, 9 Vicarage Hill, South Benfleet, Essex SS7 1PA, England. For a sample issue, send £5.50 (UK) or $11 (US/Canada, airmail). Please make checks payable to G. H. Bradley. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. |