Search Results for 'Carolyn Wells'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 7 May 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

CAROLYN WELLS – The Wooden Indian. Fleming Stone #41. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, US, 1935.

While obviously a mystery novel, maybe even a work of detective fiction, The Wooden Indian is very nearly a fantasy, simply because its resemblance to reality is so razor slim.

At least, I *think* it’s slim. It takes place in the Connecticut of the 1930s (New London County), and the country club set is very much a part of it. It’s not a world which I was ever a part of, then or now, and maybe it’s my fault. Maybe I just don’t recognize how close to reality it really is (or was).

At any rate, David and Camilla Corbin are valued members of the Pequot Club, but they are not very happily married. He is wealthy, a stamp collector, and an amateur historian specializing in local Indian legends. She is serenely beautiful, subject to scathing comments from her husband, and every other unattached male in the neighborhood is attracted to her like moths to a flame.

Wait. There’s more. Legend has it that a curse is upon the Corbin family, and every 100 years one of them will die at the hands of the spirit of a vengeful Indian chief, with bow and arrow. This is the year — and this the stuff of which detective stories are made. It’s no wonder that a friend of Fleming Stone, noted criminologist, calls him in, even before the first murder occurs. As stated on pp.26-27: “Bob’s wire didn’t promise a case exactly, but it held out interesting hopes …”

In other words, what we are playing here is a game. The rules are fixed. The victim has no say in the matter, even though his identity is known 80 pages in advance. [WARNING: Major Plot Alerts in the Paragraphs ahead.] There is a ghost at hand, there is even what is described on p.191 as a “locked room”, even though the murder took place 80 pages before that and this is the first (and last) time it’s mentioned.

The solution, by the way, describes (in some detail) the trick the killer used to get in, and yet the only thing blocking the doorway was the red cord used by the dead man to signal that he was listening to the radio and did not want to be disturbed. When Stone came upon the scene earlier, he “lifted one end of the red cord from its hook and went in,” (p.109)

While the book is listed in Bob Adey’s book on Locked Room mysteries, I must have missed something.

The killer is not the secretary, as Fleming Stone first surmises. (Apparently the last mystery Stone has read was The Leavenworth Case, and evidently, in that one the secretary *was* the killer.) Instead it’s a trivial variation on the “person most likely” — in other words, a person so obvious that I thought that that was the gimmick. Sorry. No such luck.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 31, May 1991, considerably revised.

NOTE: Obviously forgetting I first read this book back in 1991, as above, I read and reviewed it again on this blog here in 2009. These comments followed Bill Pronzini’s take on it here, a 1001 Midnights review.

Sat 31 Jan 2015

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[12] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

CAROLYN WELLS – The Clue of the Eyelash. J. B. Lippincott, 1933; A. L. Burt, reprint hardcover, no date; Triangle, reprint hardcover, 1938.

Fleming Stone, called the “ubiquitous” by the publisher most bafflingly, but maybe they mean he has appeared in many books, is dining at the home of Wiley Vane, dilettante collector of old coins, rare books, etc, along with a number of other guests. One of his relatives finds Vane shot in the head, but dinner goes on nonetheless. Wouldn’t want to announce his murder and ruin a social event, would we?

The only clue Stone has is a false eyelash, an item that he is not acquainted with, but that he and we become all too familiar with as the novel progresses, if that is what it does indeed do.

The murderer was evident early on to this reviewer, who doesn’t spot many, although the motive wasn’t transparent. But I fancy my incorrect theory of why the crime was committed a lot more than I do the murderer’s alleged reason.

A tedious investigation by Wells’s Fleming Stone, but interesting in that Stone is twice given strychnine by the murderer and survives. Stone, knowing that the murderer would try to dispose of him in this fashion — how he knows this is never provided to the reader and why he takes the poison is another secret — has his doctor’s word that a tumbler of “strong spirits” taken shortly before the strychnine will make the poison ineffective.

The author says this is a fact, and I’m not going to experiment to disprove it. The murderer tries to poison Stone again, in a triumph of hope over experience, but Stone once more has taken strong drink rather than demur at taking the poison.

One does wonder who the human guinea pigs were who tested this counteragent and what might have been the fate of those who drank only, say, a half tumbler.

A novel for those who will read anything.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 1, Winter 1990.

Mon 30 Dec 2013

Posted by Steve under

General[8] Comments

A Ballade of Detection

Savants there be who joy to read

Of lofty themes in words that glow;

Others prefer the poet’s screed

Where liquid numbers softly flow.

Others in Balzac interest show,

Or by Dumas are much impressed;

Some seek grim novels of woe–

I like Detective Stories best

To my mind nothing can exceed

The tales of Edgar Allan Poe;

Of Anna Katharine Green I’ve need,

Du Boisgobey, Gaboriau;

I’ve Conan Doyle’s works all a-row

And Ottolengui and the rest;

How other books seem tame and slow!

I like Detective Stories best.

The dim, elusive clues mislead.

Hiding the mystery below;

To fearful pitch my mind is keyed,

Opinion shuttles to and fro!

Successive shocks I undergo

Ere the solution may be guessed;

Arguments and discussions grow–

I like Detective Stories best.

ENVOY:

Sherlock, thy subtle powers I know,

Spirit , incarnate quest,

To thee the laurel wreath I throw—

I like Detective Stories best.

— Carolyn Wells

NOTE: Reprinted from The Bookman, March 1902. Thanks to Victor Berch for unearthing this poem and sending it along to be posted here.

Sun 6 Jan 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

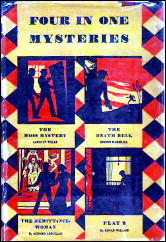

CAROLYN WELLS – The Moss Mystery. First appeared in Four in One Mysteries, Garden City Publishing, hardcover, 1924. 119 pages. [Other novels in the same volume: Flat 2 by Edgar Wallace, The Death Bell by Edison Marshall, and The Remittance Woman by Achmed Abdullah.]

“I am a living man, and he is a Fictional Detective, but that is the only way in which I radically differ from Sherlock Holmes. We are both wonderful detectives, and I know of no other in our class.” Thus sayeth Owen Prall, who then goes on to add to the misquotation: “Elementary, really, my dear Watson.”

Readers of my reviews are aware that I am easily taken in by specious authors, which Wells to her credit, even when she may be trying, generally isn’t. As Prall is presented with the case he has desired his entire career — murder in a locked room — I was delighting in the spoof that Wells was engaged in as she made fun of her detective, whose ego is enormous. Reluctantly I was soon forced to conclude that Wells was serious in her intent, but this doesn’t detract from the pleasure of reading this short novel as a parody. If you wish to read it for other reasons, so be it, but don’t blame me if it is then far less enjoyable.

— From

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 4, Fall 1992.

Tue 14 Sep 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CAROLYN WELLS – The Umbrella Murder. J. B. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1931.

Some enterprising satirist should put Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe in a Carolyn Wells’ mystery novel. Given Chandler’s scathing disdain for the rich and socially connected and Wells’ disproportionate admiration for them, the resulting clash of temperaments would be interesting.

In 1931, Dashiell Hammett was making the “hardboiled” style appetizing in the United States, but unflappable Carolyn Wells breezed right on in her usual manner, seemingly oblivious to new trends in crime (though, interestingly, she included Hammett stories in her mystery tale anthologies). The Umbrella Murder sees foul death strike at a fashionable Club Spindrift in coastal New Jersey.

“Neither effort nor expense was spared to make the best and most elaborate beach resort in the country,” reports Wells breathlessly. “The Clubhouse was a gem in itself, and the Casino was another. It was all exclusive, and expensive.”

You might think that someone is murdered with an umbrella at Club Spindrift, but, ha, if so, Wells has fooled you. It seems that wealthy and beautiful heiress Janet Converse has been dispatched with a poisoned syringe while sitting under a beach umbrella, clad in her gaily striped beach pajamas, this season’s “IT” fashion trend (disappointingly, the splendid art deco dust jacket shows the expired Janet clad in polka dot pajamas — given the amount of time Wells devotes to describing the beach pajamas worn by Janet and the girls in her “crowd,” you would have thought cover artist Irving Politzer would have gotten this detail right!).

At one time there were about twenty people, all Janet’s crowd, gathered under the umbrella, so I was wondering whether “The Beach Tent Murder” might have been a more accurate title. Hey, you have to occupy yourself somehow when reading a Carolyn Wells mystery (incidentally, the umbrella on the dust jacket simply could not have afforded shelter to that many people).

But, anyway, Fleming Stone, you may not be surprised to learn, was on the beach; and he soon is pulled into the case, the locals being jaw-droppingly incompetent. It takes Stone, who has horned in on the autopsy, to discover the “minute puncture” on Janet’s left hip. The Great Detective knows what to do next:

“Now, if one of you doctors will cut into the heart, the upper part, and be quick to note any odor–“

“My God!” exclaimed Cutler, “you don’t mean–”

But the coroner made the incision advised by Stone, and immediately both he and Cutler were conscious of a faint smell of bitter almonds:

“Prussic acid!” Cutler cried….

After this interesting scene, the police are obliged to investigate Janet’s crowd, though they have trouble believing the murderer could be one of those “rollicking youngsters,” naturally popular and beloved by all on account of their good looks, stylish clothes, fine breeding and lavish living.

As one man avows: “Those girls are as handsome as any I ever saw, and the boys are thoroughbreds.”

Unfortunately, compounding the disturbing social scandal, a diamond necklace Janet was carrying in a pocket of her beach pajamas (don’t ask) has disappeared, apparently stolen. Worst yet, suspicion starts to center on Janet’s fiancee, Stacpoole Meade, one of the richest of this rich set (his father is Stuyvesant Meade, so that should tell you something).

Surely a son of Stuyvesant Meade couldn’t be involved in murder and theft?! Thankfully, Stacpoole Meade manages to prove his innocence when he gets murdered too.

Meanwhile, back at Janet’s home, a mock castle overlooking the beach named Twin Turrets, Janet’s aunt and heir, spinster Jane Winthrop, is having to deal with an apparent apparition haunting one of the aforementioned turrets, demanding the return of its “treasure.” Fortunately Aunt Jane has a staunch friend in her Irish housekeeper, Molly Mulvaney, who, just to make sure the reader knows she is Irish, says things like this:

“Mercifulation! What a coil! Not only is the poor darling dead, but all the kickooin’ there”ll be straightenen’ of it all out.”

Then Aunt Jane disappears, seemingly kidnapped, perhaps murdered. And a distant cousin shows up to claim the estate (assuming Aunt Jane is dead too). And a strange elderly detective, Humphrey Holt, appears on the scene as well, announcing he wants to help Fleming Stone crack the case. Fleming Stone has his hands full with this one!

WARNING: FURTHER DISCUSSION OF THIS SPLENDID LOOPINESS OF THIS TALE NECESSITATES THE INCLUSION OF MAJOR SPOILERS CONCERNING THE SOLUTION

I’m certain you’ll be amazed as I was to learn that Fleming Stone reveals that Humphrey Holt is really Aunt Jane in disguise! Why did Aunt Jane disappear to do a drag routine? Well, let Aunt Jane explain it herself:

“[T]he only way I could get Janet’s murderer was to pretend to be a detective and so have an opportunity to investigate. Also, I must pose as a man, for a woman detective is no good, and too, I’d be recognized.”

So the intrepid Aunt Jane plucked her bushy eyebrows, “had a new double set of false teeth made” (quick work!), “got her hair shingled and thinned out” and had her brother, with whom she was staying, coach her “in the matter of manly action” (I told you, don’t ask). And she was able to fool everyone in town once she returned, except Fleming Stone, of course.

I’m sure this makes perfect sense to you too.

The most astounding revelation of all, however, is that the murderer turns out to be Janet’s best friend, that beautiful blonde, Eunice Church. We learn to our horror that Eunice is “almost, if not quite, insane” and that she killed Janet and Stacpoole out of jealously over their engagement. After Eunice dispatches herself with another hypodermic syringe (such handy things), Fleming Stone is left free to explain his brilliant deductions to the surviving characters:

“Perhaps you’ve noticed [Eunice’s] mannerism of tucking her thumbs into her curled fingers… That is a sure sign of weakness of character, degeneracy, and even criminal tendency. Then, her head is flat at the back. That is positive proof of hatred, revenge and jealously….[And her ears are] pointed at the top, [with] broad and heavy lobes, and a thin helix…It all points toward a criminal nature… Then her thin lips, her eyes, steel blue at times, though often violet, and her prominent muscular jaw, in spite of her soft chin, all meant homicidal mania that was sure to break out upon provocation.”

Wow! Clearly Eunice should have been drowned at birth. Unfortunately for her criminal schemes, she failed to consult Aunt Jane in disguise techniques, and she fell under the the penetrating gaze of Fleming Stone, an obvious student of physiological criminologist Cesare Lombroso.

How any of this is really fair play detection I don’t see, but apparently Carolyn Wells’ fans were more interested in the details on those smart and fashionable beach pajamas.

One thing I will say in this tale’s favor: Eunice’s hiding place for the stolen diamond necklace (well of course she perpetrated that too — heck, if she hadn’t been stopped cold by Fleming Stone, we probably would be reading about “Eunice and Clyde” today) is quite clever, and reminds me of certain stunts by Dorothy L. Sayers and John Dickson Carr (an adolescent admirer of Miss Wells). I won’t spoil that part!

The rest is purest Gun in Cheek material. The reader is warned.

Editorial Comment: One of the books by Carolyn Wells that Curt has reported back on in recent weeks, and much more favorably, was The Furthest Fury. You can read his review here.

Wed 8 Sep 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CAROLYN WELLS – The Furthest Fury. J. B. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1924.

After over a half-dozen attempts I have finally found a Carolyn Wells mystery I like. It’s called The Furthest Fury. Character drawing is adequate to good, Wells’ “transcendant detective” (as he is called here) Fleming Stone is present for about half the book — actually detecting — and the solution is acceptably fair to the reader.

David Stanhope’s visit with friends in the Connecticut hill country village of New Midian soon plunges him into mystery as two comparatively recent citizens of the village, a man, Nevin Lawrence, and his widowed sister, are murdered in their own house, both shot to death.

Potential suspects include the hotheaded son of Stanhope’s wealthy friends, who was running for country club president against Nevin Lawrence on a “wet” platform; the son’s girlfriend, a mere daughter of the local dressmaker; the peppery maid, who inherits under the wills; the local spinster music teacher, a gossip and busybody of the first order; the strange, white-faced man Stanhope noticed on the train to New Midian; and possibly even the landlord and landlady and various summer residents of the local genteel boarding house, “Gray Porches.”

Along with the far-too-bumbling local police, Stanhope investigates the brutal crimes; but he finally is compelled to call on Fleming Stone, who answers all questions after some genuine detection. Stone leaves his theory of the crime in a sealed envelope early on during the course of his investigations — and he was dead-on accurate, of course!

The atmosphere of the once-peaceful little New England village is fine — it’s a convincing sort of American Mayhem Parva. Additionally, there’s some well-portrayed generational conflict between a father and son, an appealing (not cloying) lower-class damsel, a fine “character” of a maid, and a memorable gossipy spinster. The solution is quite interesting, and the reader may well deduce it.

All in all, The Furthest Fury is a fine book, well worth reprinting. The silliness omnipresent in so many of Wells’ post-1920 books is not present, nor is the book stilted and dated in the Victorian manner like many of her earlier mysteries. And, best of all, the tale is fully fair play, the first such, actually, that I have read by Ms. Wells. Well worth reading!

Tue 31 Aug 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CAROLYN WELLS – Murder in the Casino. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1941.

After reading The Gold Bag (1911, reviewed here ) and Feathers Left Around (1923, reviewed here ) — early and middle period Wells efforts respectively–I thought I would try a late one, Murder in the Casino. A casino setting might be interesting, I thought.

That was back in September 2009. Nearly a year later, I have finally forced myself to finish the book. Verily, dear readers, I hope the suffering I went through on your behalf with this one is appreciated.

What is Murder at the Casino about, you must be eagerly wondering. Well, one thing it is not about is a gambling casino (that might have threatened the merest modicum of excitement).

There is a murder at a sort of public entertainment hall for dances and this sort of building can be called a casino, but, for all the use Wells makes of the setting, the murder might have taken place at the opera, the bridge party, the flower show, et cetera — you would just have to take her word for it. This is probably the blandest mystery novel I have ever read.

To the extent this book is about anything, it is about lovely Rennie Loring. Or more exactly, Rennie’s eyes, to which Wells devotes the first chapter ( “Rennie’s Eyes”), as well as the last sentence of the tedious tale.

The author wants her readers to understand that the merest look from the intoxicating Rennie can conquer all men in her path. In short, Rennie is one of those tiresome Carolyn Wellsian child-women, ingenuously advanced in the art of coquetry but otherwise an absolute nitwit.

Wells had been perpetrating such characters since before World War One, but apparently her audience had an endless appetite for them, even on the eve of Pearl Harbor and the advent of Rosie the Riveter. So I suppose whether you like Murder at the Casino will depend a great deal on how much you like reading about idiot savant coquettes.

Renny’s brother and sister-in-law help get her married off to Nicholas Talbot, the richest man in the very rich suburban Connecticut community in which they live with Renny. Charming Renny throws over her old boyfriend to marry Mr. Moneybags. Unfortunately, Talbot proves to be a jealous tyrant.

As Wells interestingly puts it, Talbot had “a latent Othello complex, which it were wise not to monkey with.”

The couple take their honeymoon in Mexico City (though it could have been in their own backyard, for all the writing conveys of the atmosphere), and an inspired Renny, once back home, decides she wants to put on a Mexican dance at the local casino:

“Shall we have real Mexican girls and young men, or our own crowd, fixed up?” asks Renny. “Our own people, of course,” her husband declares. “We don’t want those brown folks around!” So the fun goes ahead, sans authentic “brown folks,” and with Renny dancing the lead female part and Talbot’s nephew the lead male part.

Describing this dance affair, Wells takes time, as was her wont, for a little fashion show commentary:

Renny’s costume … was a full red skirt with a green yoke, spangled all over, with a white silk low-cut blouse embroidered with beads of all colors … Steve Trask as the charro, was gorgeous in long, tight leather trousers, covered with silver buttons and chains, a soft leather jacket, braided in silver and gold, and a gorgeous serape.

If this were Agatha Christie, there would be something sinister about that serape, but, unfortunately this is Wells, and she is much more interested in pure fashion than murder, so what you see is all you get. Though a murder finally does take place, during the dance, when Rennie’s husband –surprise! — is stabbed to death.

For the rest of the book the wealthy locals emphasize that the foul deed must be the work of the radicalized lower classes (Emma Lazarus, what hath though wrought?!):

“Must have been…some disgruntled Communist who resented Nick’s wealth.”

“I suppose it must have been some of those bad men who hate rich people. You know what I mean, Reds, they call them, I think.” (Yes, this is Rennie.)

“You think, then, Rudd, that it was some laborer or workman?”

“I think the wicked man who who killed Steve was the same sort of man that killed my husband. Those bad people who make strikes and things.” (Yup, Rennie again, this time after a second dastardly murder.)

It would be pleasant to believe this is intended as social satire, but as Wells gives every indication that she greatly admires the stupid people of this wealthy suburban Connecticut town ( “a restricted residential district”), I think she is serious. You would honestly think it was 1886 and that the Haymarket Riot had just occurred.

Much of the dialogue in this tale (and the tale is mostly dialogue) is written as if the author’s first language were not English:

â— “Then I’ll give my advice to you… Put a little more dignity into your own performance, and curb your tendency to amorous gestures and tones. They are uncalled for and they greatly mar the picture.”

â— “It is hard to be sure, but I think Mr. Talbot believed the beneficent inscription, and that later, only yesterday, in fact, he learned the true translation, and that being attacked, he tried to get the ring off, and did so, but it was too late, and he dropped the ring under him, where it was later found by the detectives.”

â— “Yet the conditions are simple. Renny Loring and I have been in love for years. Along comes Talbot, and gets her away from me by reason of his great wealth and position and general attractive qualities.”

â— “I am an astronomer, Inspector, and on occasion I view the Heavens to see what the planets are up to now. The great windows in these halls offer fine views to a student of astronomy, and I enjoy them greatly.”

Wells’ greatest Great Detective, Fleming Stone, shows up and solves the case, though no discernible process of ratiocination that I could detect. Rather, Stone simply announces he knows who the killer is and the killer promptly confesses and kills him/herself with yet another one of those convenient poison pellets one finds so much in Golden Age tales, particularly those penned by Carolyn Wells.

Talk about dumb! This person must have been even dumber than Renny.

The entrancing and filthy rich Renny, by the way, does not the know the meaning of “berserk” or “privileged communications” and says “electricated” when she means “electrocuted.” Surely this helps explain why there is no chapter in Murder at the Casino entitled “Rennie’s Brain.” It would have had to have been a very short chapter indeed.

Murder at the Casino was apparently Wells’ seventy-ninth mystery tale (I cannot bring myself to call them detective novels). Two more Wells mysteries would be published after Casino in 1942 (one I believe posthumously).

My copy of Casino, published by Lippincott, a major publisher, is a very attractive volume: well-bound, good creamy paper, an excellent dust jacket. Lippincott must have known what it was doing publishing these later Wells books, but I cannot fathom why people enjoyed reading them. My only guess is that they were 1941’s version of “cozies,” but that guess it sort of insulting to many modern day cozy writers.

Perhaps the best comparison might be with the books Lilian Jackson Braun was writing in her nineties, before her publisher, Putnam, finally dropped the series in 2007. However classically “alternative” (to borrow a term from Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek) Wells’ earlier mysteries may be, they cannot match Murder at the Casino for sheer inept daftness.

Fri 18 Sep 2009

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CAROLYN WELLS – The Gold Bag. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1911. Silent film: Edison, 1913, as The Mystery of West Sedgwick. Online text: here.

“Though a young detective, I am not entirely an inexperienced one, and I have several fairly successful investigations to my credit on the records of the Central Office. The Chief said to me one day: Burroughs, if there’s …”

The prolific American writer Carolyn Wells was mocked by Bill Pronzini in his entertaining book on “alternative” mystery classics (books so bad they’re good), Gun in Cheek, for having written an instructive tome on the craft of mystery fiction, The Technique of the Mystery Story (1913), and then seemingly failed to follow her good advice when composing her own mystery tales.

Wells’ second detective novel, The Gold Bag — which actually precedes The Technique of the Mystery Story by two years — illustrates Pronzini’s thesis. It might well have been titled The Leavenworth Case for Dummies.

Carolyn Wells was first drawn to reading mystery fiction in her mid-thirties when a neighbor lady came calling on Wells and her mother and read to them some of Anna Katharine Green’s latest detective novel, That Affair Next Door (1897) (Wells, by the way, suffered hearing loss as a child and wore a hearing aid throughout her life.)

Green had published a hugely popular mystery novel, The Leavenworth Case (1878) nearly twenty years earlier, and had settled into a comfortable career as a prolific crime writer.

Though I personally find it unreadable due to the stilted, melodramatic speech-making of its characters (particularly the two nieces), The Leavenworth Case is considered a seminal work of mystery fiction and is still taught today. Moreover, it does have a solid plot and is fascinating for being an early instance of so many Golden Age mystery tropes: the millionaire murdered in his mansion study/library, the retinue of suspicious servants, the beautiful niece (in this case two), the private secretary, the will.

Wells clearly was familiar with The Leavenworth Case, because The Gold Bag, her follow-up to her debut detective novel, The Clue (1909), obviously is modeled on Green’s famous tale.

In The Gold Bag there is a Watsonesque narrator figure, as there is The Leavenworth Case (in this case Burroughs, apparently a private detective — Wells is never clear on realistic detail like this). As in Leavenworth, this figure is called in to be involved in a murder investigation, this one in a wealthy town in New Jersey (probably, one suspects, quite like Wells’ own home town).

The case involves a millionaire murdered in his study, a retinue of suspicious servants, a beautiful niece, a private secretary and a will. (Sound familiar?) As in Leavenworth, a great deal of time is spent on the coroner’s inquest. As in Leavenworth, the Watsonesque figure becomes enamored with the beautiful niece suspected of the crime. Will true love prevail? What do you think?

Following Leavenworth by over thirty years, The Gold Bag is written in a sprightlier style and reads much more quickly. Where it falters is in providing an adequate puzzle. Wells’ putative Great Detective, Fleming Stone, appears briefly at the beginning of a 325 page novel, then returns in the last twenty pages to solve this case.

If this suggests to you problems with the solution, you are right. Most of the novel is devoted to Burroughs’ investigating various trails (including the trail of the gold bag of the title), all leading to different suspects, and all proving false. During virtually the whole novel, Burroughs, when not pining for the niece, is lamenting how the great Fleming Stone is not around to solve the case for him, until you just want to thrash him.

When Stone does show up he eliminates one suspect on the basis of deductions he had made some days ago about some shoes left out to be cleaned at a hotel, shoes that just happen to turn out to have been the shoes of this suspect!

“It is very astonishing that you should make those deductions from those shoes, and then come out here and meet the owner of those shoes,” pronounces another character. I’ll say!

Then Stone pulls the murderer, the only person left not suspected at some point in the novel, out of his hat, and the fool hysterically confesses his/her guilt and commits suicide with one of those convenient poison pellets Golden Age murderers always seem to have handy when the Great Detective points the Dread Accusing Finger at them.

This leaves one page for the author to pair off Young Love, and all ends happily ever after (except for the murderer, but readers will barely remember him even one page after his exit).

So, with disappointing detection, no clever murder mechanics, cardboard characters and no interesting descriptive writing, there is not much to recommend this one, except from a sociological standpoint.

It’s not really bad enough, either, to qualify as one of Pronzini’s alternative classics. Notably lacking here is the rather silly humor and situations found in many of Wells’ later detective novels.

There is still an air of unreality about the whole enterprise, however. The murdered man was a businessman of some sort, but we never learn anything about his business. A police investigator is briefly mentioned, but he does nothing. Indeed, it seems to be the view in the The Gold Bag that coroners and district attorneys rely exclusively on private investigators to conduct murder cases for them, without any involvement from the police.

One is left with the impression that Wells had a rather limited acquaintance with what might be termed “real life.” Granted, Golden Age novels often did not stress realism, but Wells’ novels seem to me too far removed from any semblance of it.

If they were clever Michael Innes-ian parodies of the form that would be one thing, but they don’t seem to be that either. So far they just seem to me mildly silly.

But, given their apparent popularity, they do show that there was a mystery fiction audience in the United States over the period Wells published mystery novels (1909-1942) that must have been far, far removed in taste from the celebrated hardboiled style.

Note: Curt hasreviewed another book by Carolyn Wells on this blog, Feathers Left Around, from 1923.

Thu 23 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[18] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CAROLYN WELLS – Feathers Left Around. J. B. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1923.

Perhaps the most perfect example of the stereotypically bad English country house mystery that I have read was published in 1923 by an American, Carolyn Wells. Sure, Feathers Left Around takes place in America, but it might as well be in the England of the classic Golden Age country house fantasy land of stereotype.

The best thing about the tale is the whimsical title, the meaning of which we learn from this racially insensitive anecdote from one of the characters, the soon-to-be-murdered detective novelist, Mr. Curran:

“An old darky was arrested for stealing chickens, and he was convicted on circumstantial evidence. ‘What’s circumstantial evidence?’ a neighbor asked him. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘ez near as I can splain f’um de way it’s been splained to me, circumstantial evidence is de feathers dat you leaves lyin’ roun’ after you has done wid de chicken.'”

So the “Feathers” in the tale are the clues left around after Mr. Curran is found dead in a locked room, presumably murdered. About 80% of the novel is devoted to the bumbling efforts of a lone police detective and a surfeit of amateurs (five or more!) to solve the case, until Fleming Stone and his “saucy” boy assistant Fibsy show up to solve the case in short order.

If this suggests that the mystery is a pretty simple one, you’re right. I penciled the solution in the margin on page 102, but had to wait about 240 pages for confirmation (I was right).

No secret passages this time, but another trick that was used, with far more elaboration, by later authors John Dickson Carr and Nicholas Blake. This is the most interesting part of the book as far as plot is concerned, and might have made a mildly interesting short story. The murder method is fairly clued too, though the motive is deduced by Fleming Stone based on information not provided to the reader.

Unfortunately, the novel is padded with ceaseless dialogue among a group of completely uninteresting ciphers, which soon becomes tedious. None of the men, with the exception of the imperious host of the house party, are really distinguishable, while one wishes that the women were extinguishable.

There’s the pouty flirt who wraps all men around her finger (even the police detective, who, enchanted by the little lady’s pouts and simpers, agrees to lie about her having enjoyed a tete-a-tete out on the balcony with the deceased shortly before he died); the obvious heroine with a not-so-dark and easily-guessed secret; and the girl who likes to talk about her dreams and the utterly unconvincing Russian Countess. ( “Fiddle-dee-dee!” the Countess exclaims exotically at one point.)

It becomes clear that there’s not a chance the author will allow one of these darling women to be the killer, their obviously being intended merely to provide “character interest” window dressing (variously humor and anxiety, as the case calls for).

The author’s frivolous treatment of her female characters is further indicated when the men of the party inform the women that they are not allowed to investigate the murder scene for clues, this being man’s work, and the women submissively assent. Agatha Christie, where are you!

Most fascinating about Feathers Left Around are the author’s attitudes about gender and especially class. It seems clear Wells has no clue what an actual police investigation is like, or, if she does, she determinedly keeps that knowledge to herself.

When the five or so men of the party inform the detective that they want to accompany him to the scene of the crime to look for clues, the detective happily acquiesces, even though it’s quite apparent that one of these men may be the murderer.

When the police detective comes to suspect that the fiancee of the house party host is implicated in the crime, the latter man orders the detective out of his house and threatens to kill him if he doesn’t leave. The detective meekly retreats.

He does, however, terrorize the housemaids and threaten them with life imprisonment on bread and water in rat-infested jails if they do not answer his questions, and even allows one of the “gentlemen” to treat them so as well. (These scenes clearly are intended to be amusing.)

In terms of social attitudes conveyed by the author, it could be England in 1860, with the police investigating the Constance Kent case. It’s instructive to compare this novel with the hardboiled tales that have come to represent American mystery — the contrast is remarkable.

Far more than most Golden Age British tales I have read, Feathers Left Around strikes me as a real relic from the nineteenth century. That novels like this had a decent following (mostly female, judging by the book ads in the back of the book) suggests there was a significant conservative mystery audience in the United States as well as in Britain.

Unfortunately, the novel also suggests that, though she may have had some mildly interesting plot ideas, Wells did not offer much else to engage the reader, aside from the sociological standpoint. Wells seems rather like an American Patricia Wentworth, though even the cozy Wentworth gives a more rigorous read, in my experience.

I want my next Wells to come from near the end of her career (her last novel was published in 1942) to see if the events of the thirties ever induced her to modernize her style. Or was she still holding those same endless country house parties with the same boring society people during the Great Depression and World War Two?

Sat 18 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[27] Comments

CAROLYN WELLS – The Wooden Indian. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, US, 1935.

A recent replacement of a hot water heater in our basement necessitated the moving of several boxes of books in order in order to make room for the old one to be dragged out and the new one brought in. This brought to the light of day (figuratively speaking) several shelves of other books that I was glad to lay my eyes on again. It had been six or seven years, at least.

I am talking several hundred books in total — being moved and/or coming to light again — and of these, I picked one to read, not realizing at the time that Bill Pronzini had beaten me to it. One of his reviews from 1001 Midnights is of this same book and was posted here on this blog back in January of this year.

This is a Fleming Stone mystery, and while Bill called him “colorless and one-dimensional,” I’d say he’s a step or two above that in both categories, but on the other hand, he’s certainly no more than that.

Dead is a man whose demise is so certain, and at the hand of another, that Bob Barnaby, a friend of Stone’s staying in the same elite area in Connecticut (near the Pequot Club Grounds, a center of the book’s activities), senses it too, and calls him in on the case long before the murder actually happens.

It seems that David Corbin, a noted stamp collector as well as that of Indian memorabilia, is rather a bully to his wife, in public, at least, and his wife is also one of those beauties who suffers in silence while attracting other men to her like, well, moths to a flame.

The murder weapon is an arrow, fired from the bow of, well, guess what, a wooden Indian in full regalia in the dead man’s study. There is limited access to the room, but I do not believe that the mystery could really be called one of the locked room variety.

I’d expected the story to be stodgy and formal, but I was in error in that regard. The banter is generally witty, although of the upper crust type– no dark and dirty streets here — and the tale is heavy on dialogue, so much so that one must stop every once in a while and trace the paragraph back to rediscover who it is that’s talking.

This is also one of those books in which all of the suspects are gathered together in one room for a final confrontation, whether it’s necessary or not. Stone claims not to have known who the killer was until the very last moment, but an even less than astute reader should know from the questions he’s been asking who it is that he suspects long before then.

As a detective story, then, The Wooden Indian lands solidly in the “mediocre” category. Enjoyable enough, but distinctly below par. Bill concludes his comments about Carolyn Wells’ detective stories in general by saying, “… the casual reader looking for entertaining, well-written, believable mysteries would do well to look elsewhere.”

While I’m far from discouraged enough to say I’ll never read another one of her books, I’d have to say that I’m not especially encouraged to do so either — not immediately, at any rate.