Search Results for 'Carolyn Wells'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Mon 2 Feb 2009

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

CAROLYN WELLS – Anybody But Anne. J. B. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1914.

Anybody But Anne shares most of the characteristics of Wells’ later Faulkner’s Folly (reviewed here not too long ago):

● It is a full, formal mystery novel, of the kind that would later be popular in the Golden Age.

● It is set in a country house, and anticipates the mysteries soon to be popular in such houses.

● The cast of suspects resemble those to be found in many later detective books.

● It is a locked room mystery — but the solution of the locked room is based on ideas that would later be regarded as cheating. Still, the cheat of a solution shows some real ingenuity.

● The book shows the imagination with architecture, that would later be part of the Golden Age. It comes complete with a floor plan. The country house is of the kind that might have later inspired the mystery game known as Clue or Cluedo: there is even a billiard room!

● Wells pleasantly includes some subsidiary mysteries, that have nothing to do with the locked room. These too show some mild but pleasing ingenuity. Such subplots are also standard in Golden Age detective novels.

I do not know if Wells invented the above template for formal mystery novels, or whether she derived it from other authors. Anybody But Anne does establish, that what we think of as a “typical Golden Age style mystery novel,” was in existence before what is often thought of as the official start of the Golden Age in 1920. It is also a fact, that Wells was American, and that her book is set in the United States: somewhere in New England.

The best parts of Anybody But Anne have charm. People looking to sample Wells, might enjoy this novel, or at least its best chapters. It is at its best in the opening (Chapters 1-6), which sets up the architecture, characters and murder mystery; two later chapters that tell us more about the house as well as exploring some subsidiary mysteries (14, 17), and lastly the solution (Chapters 18, 20). Together these sections make a readable novella. The novel has been scanned by Google Books, and can be read free on-line.

We get a good portrait of Wells’ sleuth, Fleming Stone, in action in these sections. Oddly, he is missing in most of the middle of the book, sections which generally are not that interesting anyway. Like most pre-1945 detectives, he is more characterized by his skills and behavior as a detective, than by any knowledge we get of his personal life.

Stone has a penetrating intellect, that goes right to the heart of clues to the mystery, in the evidence at hand. He is crisp and business-like at delivering his insights, sharing his ideas immediately with the other characters and the reader.

We do learn that Fleming Stone is outside of the world of romance, like many other early detectives. Wells gives an interesting psychological portrait of this.

Thu 29 Jan 2009

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

CAROLYN WELLS – Faulkner’s Folly.

George H. Doran Co., hardcover, 1917. Serialized in All-Story Weekly, September 8 to September 29, 1917.

Carolyn Wells’ Faulkner’s Folly (1917) is the first novel I have read by that author. It shows the frustrating mix of (artistic) virtue and vice that other commentators have discerned in her work.

The book is startlingly close to the traditions of the Golden Age novel. But it was written before Christie, Carr, Queen, Van Dine and other intuitionist Golden Age writers had published a line. And this is hardly Wells’ first work; she had been publishing for over a decade, since 1906, when this novel appeared.

The novel has an apparent medium who holds séances, etc., and whose “supernatural” gifts are ultimately explained naturally; this seems very anticipatory of both John Dickson Carr and Hake Talbot. Carr was in fact devoted to Wells’ works while growing up, and we know from both Ellery Queen and Carr biographer Douglas G. Greene that he was one of Wells’ biggest admirers. Many of Wells’ tales are impossible crime stories; she was apparently one of the first to expand this genre from the short story to the novel, following Gaston Leroux.

Faulkner’s Folly also anticipates the Golden Age in other ways. It takes place in an upper class country house, and draws on a closed circle of suspects of relatives, guests and employees of the murdered man. There is an atmosphere of culture to the novel, too; the murdered man was a great painter, and one of his guests is the widow of the architect who built his mansion. The whole novel is very close in tone to S.S. Van Dine; in fact it is one of the closest approximations in feel to his work among the mystery authors who preceded him.

Wells would certainly be classified as an intuitionist. She started by publishing in All Story magazine, one of the early pulp magazines that also featured the work of Mary Roberts Rinehart. But her work could not be more different from Rinehart’s.

There is no sign of an influence from Anna Katherine Green, or of scientific detection à la Arthur B. Reeve. Nor is there much suspense of any sort in Wells’ work. Instead, Wells’ book is squarely in the intuitionist tradition, and seems on the direct line to such later intuitionist writers of the Golden Age listed above.

The best part of Wells’ book is the finale, when the murderer is revealed and the various mysteries are explained. It reminded me of the pleasure I have received from the finales of Christie, Carr and other Golden Agers, when all is revealed.

Now for the down sides of Wells’ work. Her book is nowhere as good as a work of storytelling as the later authors we have mentioned. And her plot is nowhere as clever as these later authors, either. Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek (1982), his affectionate but hilarious history of really bad crime fiction, points out other truly major flaws in Wells’ works.

Her impossible crime plots tend to depend on secret passageways. This gimmick was later, during the Golden Age, regarded as a cheat; the locked room novels of Carr and others often contain solemn assurances from the author that no secret passageways were found in the buildings where the crimes occurred. To be fair, Wells showed some real ingenuity in the use of such secret panels and doors; but this gimmick is likely to annoy modern readers.

We can compare Wells’ novel with “Nick Carter, Detective” (1891), an early series detective tale. The story opens with a “locked house” crime. Nick Carter suspects secret passageways, and sure enough he eventually finds the house to be riddled with them.

They are similar to the secret passageways Herman Landon used for his Gray Wolf stories in Detective Story in 1920. Detective Story was the first specialized mystery pulp magazine. So the impossible crime caused by secret passageways was a common coin of inexpensive mystery fiction.

Carolyn Wells also used secret passages for her locked room tales in the 1910’s, although she tended to employ Occam’s razor on them. She would employ the minimum number of passages need to commit the crime, often just one. It would be strategically placed in the only spot that would allow the crime to be committed.

There was a quality of ingenuity to her placement: it was not at all obvious that a secret passage anywhere would enable the crime to be possible; the revelation that a secret passage would make the crime possible would startle the reader at the end of the story. She achieves a genuine puzzle plot effect by this approach: where is the secret passageway, and how could any secret passage possibly enable this crime?

Fri 16 Jan 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Bill Pronzini:

CAROLYN WELLS – The Wooden Indian. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1935.

During the first four decades of this century, Carolyn Wells wrote more than eighty mystery novels — most of them to a strict (and decidedly outmoded) formula she herself devised.

She has been called, with some justification, an expert at the construction of the formal mystery, and she has also been credited with popularizing the locked-room/impossible-crime type of story, of which she wrote more than a score.

Her other claim to fame is that she was the author of the genre’s first nonfiction work, a combination of how-to and historical overview called The Technique of the Mystery Story (1913). Unfortunately, that book is far more readable today than her novels, which are riddled with stilted prose, weak characterization, and flaws in logic and common sense.

The Wooden Indian, one of her later titles, is a good example. It features her most popular series sleuth, Fleming Stone, a type she describes in The Technique of the Mystery Story as a “transcendent detective” — that is, a detective larger than life, omniscient, a creature of fiction rather than fact.

And indeed, Fleming Stone is as fictitious as they come: colorless and one-dimensional, a virtual cipher whose activities are somewhat less interesting to watch than an ant making its way across a sheet of blank paper. The same is true of most of her other characters. None of them come alive; and if you can’t care about a novel’s characters, how can you care about its plot?

The plot in this instance is a dilly. An obnoxious collector of Indian artifacts, David Corbin, keeps a huge wooden Indian, a Pequot chief named Opodyldoc, in a room full of relics at his home in “a tiny village in Connecticut which rejoiced in the name of Greentree.”

One of the accouterments of this wooden Indian is a bow and arrow, fitted and ready to fire. And fire it does, of course, killing Corbin in what would seem to be an accident (or the fulfillment of an old Pequot curse against the Corbin family), since he was alone in the room at the time and there was no way anyone could have gotten in or out.

Several guests are on hand at the time, one of them Fleming Stone. Stone sorts out the various motives and clues, determines that Corbin was murdered, identifies the culprit, and explains the mystery — an explanation that is not only silly (as were many of Wells’s solutions) but implausible, perhaps even as impossible as the crime itself was purported to be.

Fleming Stone is featured in such other titles as The Clue (1909), The Mystery of the Sycamore (1921), and The Tapestry Room Murder (1929).

Wells also created several other series detectives — Pennington (“Penny”) Wise, Kenneth Carlisle, Alan Ford, Lorimer Lane — all of whom are as “transcendent” as Fleming Stone.

Her novels are important from a historical point of view, certainly; but the casual reader looking for entertaining, well-written, believable mysteries would do well to look elsewhere.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright ? 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 17 Nov 2008

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

THE CURMUDGEON IN THE CORNER

by William R. Loeser

CAROLYN WELLS – The Tannahill Tangle. J. B. Lippincott, US/UK, hardcover, 1928.

I can’t remember who killed whom in Carolyn Wells’ The Tannahill Tangle, nor have I any desire to look it up.

The feature that sticks in my mind is the two well-to-do couples who are the main characters. They are engaging in spouse-swapping, and, when one of them is killed, the perceptive reader might feel that the inherent frictions of this diversion have some bearing on the crime.

But no, the survivors and Ms. Wells take great pains to assure themselves, each other, and us that they are too “well-bred” for such messy sports as murder. Fleming Stone is called in and, as I recall, is able to find someone of less-illustrious parentage and prospects to pin the rap on.

Fortunately, I had only this one book of Ms. Wells to get rid of. It is a reminder I will not soon forget that the Golden Age produced the worst clinkers as well as the masterpieces of detective fiction.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1979 (very slightly revised).

Thu 23 May 2019

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

ALBERT DORRINGTON – The Radium Terrors. Eveleigh Nash, UK, hardcover, 1912. Doubleday Pagr, US, hardcover, 1912. W. R. Caldwell & Co., US, Hardcover, ca. 1912. Serialized in The Pall Mall Magazine, UK, January-June 1911, and in The Scrap Book, January-August 1911.

Beatrice Messonier sat near the window dazed and mystified by her benefactor’s dazzling prophecies. Something in his manner suggested an approaching crisis in his own life and hers. What did his talk of princes and statesmen mean? She would have regarded such an outburst in another as the result of alcoholic excesses. But Teroni Tsarka was not given to the use of stimulants. He abhorred intemperance of mind and body. What he had spoken was the result of his structural philosophy, she felt certain. A tremendous crisis in medical research was at hand. And Teroni Tsarka was the man to sound the trumpet of science to an apathetic civilization.

Beatrice Messonier is a brilliant oculist whose research was backed by the mysterious Dr. Tsarka, who has helped her learn the secrets of the Z Ray, the powerful result of radium research, and has set her up in a clinic, which has no patients thanks to his insistence on exorbitant fees.

Just that night she broken her own heart having had to turn down the young detective Clifford Renwick, who was blinded with radium by Tsarka’s own assistant Horubi when Renwick tried to force an interview with Tsarka about the recently stolen Moritz Radium, Renwick being a youthful private investigator eager to make a name for himself.

And of course we are off in the land of the Yellow Peril novel, serialized in Pall Mall, a popular British magazine on the lines of The Strand, and handsomely illustrated as well.

Ironically Sax Rohmer had much the same idea in about the same year, with Dr. Fu Manchu making his debut, but even with Rohmer’s rather crude Edwardian style, his work is a far cry from the maudlin at times (the blinded Renwick has a touching moment with his old gray mother after escaping Tsarka — something you can hardly imagine Dr. Petrie or Nayland Smith bothering with) and painfully arch Dorrington.

The formula here is much the same of the early Fu Manchu books, parry and thrust, chase, escape, and traps to capture Tsarka sharing about equal time with not particularly imaginative deadly traps for young Renwick.

But the devil in these details is how dated Dorrington’s novel reads compared to Rohmer, who for all his melodrama and atmosphere is practically a minimalist in comparison.

What with Beatrice Messonier (another difference is that in Rohmer, a Eurasian beauty wins Dr. Petrie’s heart, but in Dorrington, Renwick can’t be involved with a woman much more exotic than a Frenchwoman) unconvincingly posing as a much older woman and forced to seem heartless and cruel to young Renwick, and Tsarka being more interested in profit than world conquest, it is, for all its thrills, pretty pale stuff compared to Rohmer’s unknown poisons, Fu Manchu’s army of dacoit assassins, seductive Eurasian beauties under his spell, snakes, rats, weird poisonous bugs and the like.

Tsarka, like Fu Manchu, has a daughter, but she is a far cry from Fu Manchu’s child. Rather she is a pale flower whose Japanese artist lover lives with she and her father (Tsarka uses an exhibition of the young man’s work to blind several prominent people who must then seek Madame Messonier’s clinic, the extent of his evil masterplan, a cheap cruel con game to make a few bucks). I suppose the attractive lovers are a step up from Fu Manchu’s evil daughter, but frankly they don’t bring much to the proceedings rather than a bit of humanization to the cruel and crafty Japanese scientist despite his penchant for experimenting on unwilling victims.

“The scoundrel!” burst from Coleman. “He and his associates appear to have discovered a destroyer of human energy in radium. Personally, I fear that we shall find ourselves unable to cope with this new school of Asiatic criminals who regard the blinding of men and women as a pleasant pastime.”

Reading this, it doesn’t take much imagination to see Rohmer’s entry in the Yellow Peril stakes for the startlingly new and modern work it must have seemed what with a thin patina of sex, relatively clipped dialogue, and straight forward telling wrapped in the opium fog laden atmosphere of Limehouse out of Thomas Burke and pure imagination. Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss†reads as if it might have been written in the early twenties, where Dorrington’s Radium Terrors reads as if it might have been written in the early eighteen nineties.

The book has its thrills, and while dated, it isn’t badly written, but reading it you can understand what readers noted in better writers of the era, a voice, that beginning with Conan Doyle, was more modern and less given to maudlin sentiment and long winded prose. Reading Rohmer after Dorrington, or around the same time, must have been as refreshing as discovering Dashiell Hammett after a steady diet of Carolyn Wells.

Reading this can give you a new appreciation for the relative modernity of the more vulgar, and certainly more gifted Sax Rohmer. Tsarka is a mean and constipated villain, vicious, petty, and ultimately ridiculous for all the Victorian language. Rohmer’s Fu Manchu is a Miltonian angel fallen to earth — some recent Asian literary scholars have suggested rehabilitating Fu Manchu for just that reason — because the character has, both in Rohmer’s work and the public imagination, transcended his racist origins becoming an archetype as much as a stereotype.

Whether there proves to be anything to that view or not the inescapable fact of reading The Radium Terrors is that Rohmer and Fu Manchu ran literary rings around Dorrington and his Dr. Tsarka, and it may just be the difference, aside from Rohmer’s superior storytelling skills, is that Dorrington doesn’t believe in his Japanese pretender for a moment, and Rohmer embraces the his creation with full blooded zeal.

Fu Manchu lived and breathed. Tsarka lingers like a bad taste.

Fri 25 Feb 2011

The Murder of Mystery Genre History:

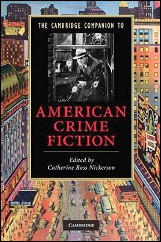

A Review of The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction

by Curt J. Evans

On the back cover of The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction (Cambridge University Press, 2010; Catherine Ross Nickerson, editor), the blurb tells us that the fourteen essays contained therein represent the “very best in contemporary scholarship.” If so, this should be a matter of grave concern to people interested in the history of the American mystery genre before World War Two.

As the Companion is a skimpy book of less than 200 pages and it has fourteen essays, potential readers should be immediately clued in to the fact that the essays tend to be rather cursory. A listing of the essays further reveals that the book’s coverage is esoteric, leaving noticeable gaps:

Introduction (4 pages)

Early American Crime Writing (10 pages, excluding footnotes)

Poe and the Origins of Detective Fiction (8 pages)

Women Writers Before 1960 (12 pages)

The Hard-Boiled Novel (15 pages)

American Roman Noir (12 pages)

Teenage Detective and Teenage Delinquents (13 pages)

American Spy Fiction (9 pages)

The Police Procedural on Literature and on Television (13 pages)

Mafia Stories and the American Gangster (10 pages)

True Crime (12 pages)

Race and American Crime Fiction (12 pages)

Feminist Crime Fiction (14 pages)

Crime in Postmodernist Fiction (12 pages)

Further evidence of highly selective coverage can be found in the “American Crime Fiction Chronology” at the beginning of the book. Here are its milestones in crime fiction from 1841 to 1939:

1841 Edgar Allan Poe, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”

1866 Metta Fuller Victor,

The Dead Letter

1878 Anna Katharine Green,

The Leavenworth Case

1908 Mary Roberts Rinehart,

The Circular Staircase

1923 Carroll John Daly, “Three Gun Terry”

1925 Earl Derr Biggers,

The House Without a Key

1927 S. S. Van Dine,

The Benson Murder Case

1927 Franklin Dixon,

The Tower Treasure

1929 Dashiell Hammett,

Red Harvest

1929 Mignon Eberhart,

The Patient in Room 18

1930 Carolyn Keene,

The Secret of the Old Clock

1934 James M. Cain,

The Postman Always Rings Twice

1934 Leslie Ford,

The Strangled Witness

1938 Mabel Seeley,

The Listening House

1939 Raymond Chandler,

The Big Sleep A pretty obvious pattern can be constructed from these fifteen fictional milestones:

The Distant Founder: Poe

The Women: Victor, Green, Rinehart, Eberhart, Ford, Seeley

The Hardboiled Men: Daly, Hammett, Cain, Chandler

The Non-hardboiled Men: Biggers, Van Dine

The Children’s Authors: “Dixon” and “Keene”

One would conclude from this list that American men donated practically nothing to the detective fiction genre after 1841 (Poe), outside of the hardboiled variant and juvenile mystery (the authors of the Hardy Boys tales). Apparently the only significant male producers in the nearly 100 years between Poe’s first story and Chandler’s first novel were the creators of Philo Vance and Charlie Chan.

But it gets even worse when we look at the actual text. S. S. Van Dine gets four mentions, all cursory, some problematic:

On page 1 his rules for writing detective fiction are mentioned, dismissively.

On page 29, he is dismissed as an imitator of Agatha Christie.

On page 43, he is called an imitator of Arthur Conan Doyle and used as the usual hardboiled punching bag for not writing about “reality” (though he interestingly is deemed “the era’s most popular writer”).

On page 136, it is claimed that The Benson Murder Case is “widely acknowledged as the first American clue-puzzle mystery”

Earl Derr Biggers gets one line, solely for having created an ethnic detective (see “Race and American Crime Fiction”).

At least these non-hardboiled make writers are mentioned! The hugely popular and admired genre author Rex Stout is another lucky lad. Though he missed the list of milestones, Stout nevertheless in mentioned in the text:

On page 47 he is noted for having merged hardboiled and classic styles.

On page 136, he is criticized, along with Van Dine, for ignoring race and gesturing “more toward Europe than actual American cities” and writing about rich white bankers, stockbrokers and attorneys (yup, “Race and American Crime Fiction” again).

On the other hand, if you are looking for anything on Melville Davisson Post, Arthur B. Reeve or Ellery Queen, forget it! They did not exist apparently; we only imagined them all these years.

Meanwhile, Anna Katharine Green gets two pages, Mary Roberts Rinehart three and Mignon Eberhart, Leslie Ford and Mabel Seeley together as a trio another two. (Heck, even the lovably loopy Carolyn Wells gets a line in this book.)

The editor of the Companion, Catherine Ross Nickerson (author of The Web of Iniquity — a book, you may not be surprised to learn, about Anna Katharine Green and Mary Roberts Rinehart — and, in the Companion, of “Women Writers Before 1960â€) lectures in her Introduction that:

“It is only fairly recently that the multiple genres of crime writing have been taken up as subjects of academic study; before that, they were entirely in the hands of connoisseurs and collectors, with their endless taxonomies, lists and value judgments. What Chandler opened up was a new way of looking at crime narratives, or rather looking through them, as lenses on the culture and history of the United States.”

This is an interesting idea indeed, but unfortunately Professor Nickerson’s own selective coverage gives us an inaccurate view of the genre and, thereby, surely, of American cultural history.

According to Nickerson, there were two indigenous creative strains in American mystery: the female domestic novel/female Gothic (the Brontes and Mary Elizabeth Braddon are admitted as influences here but not Wilkie Collins or Sheridan Le Fanu); and the hardboiled.

It seems that despite the existence of Poe, what we think of as the Golden Age detective novel was an artificially transplanted English import, about as American as scones and crumpets. Nickerson dismissively notes these “Golden Age” works for their “tightly woven puzzles and country houses full of amusing guests” and declares that they were “presided over by Agatha Christie and imitated by Americans like S. S. Van Dine.”

So if you were an American male writing mysteries that emphasized puzzles and had upper middle class/wealthy milieus, you were part of a British tradition and thus not worthy of inclusion in a historical survey of American mystery fiction. But if you were an American woman writing mysteries with puzzles and upper middle class/wealthy milieus, you were part of the American female domestic novel/Female Gothic tradition (even though some of this tradition is British and male) and you make it into the genre survey.

Make sense to you? It doesn’t to me. Personally I think Professor Nickerson should take another look at those “connoisseurs and collectors, with their endless taxonomies, lists and value judgments” who she dismisses so casually. There are still things that an academic scholar writing about the mystery genre can learn from them.

Granted, they often were men who tended to be overly dismissive of women’s mystery fiction — or at least the suspense strain in it that they mockingly termed “HIBK” (Had I But Known) — but writing important men out of the history of the genre is no way to redress the balance.

Crime literature may be about violence, but scholars of crime literature should not practice “an eye for an eye.” Doing so does not make for good scholarship.

Wed 9 Feb 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

LEE THAYER – The Scrimshaw Millions. Sears & Co., hardcover, 1932. Hardcover reprint: The Macaulay Company, no date.

There are five killings in the tale, yet The Scrimshaw Millions is not remotely exciting. What should have been a gripping family extermination murder story on the order of S. S. Van Dine’s grandly baroque The Greene Murder Case (1928), instead is a snoozer the reader has to drive himself to finish.

But finish it I did, dear readers! It takes a lot to stop this fellah from plowing through to the end of a Golden Age whodunit, even a fourth- or fifth-tier one. Heck, I’ve read a dozen mysteries by Carolyn Wells!

In The Scrimshaw Millions someone is fatally poisoning the members of the Scrimshaw family one by one. A fortune is at stake — who will survive to inherit? And how long will it take for you to cease caring one iota?

To be fair, The Scrimshaw Millions struck me as superior to the books described earlier on this blog by Francis M. Nevins. The prose is serviceable, lacking those purple passages quoted by Nevins (at least until the cosmic retribution denouement Nevins has noted as a common feature of her books).

The characters, while sticks, are not irritating (except when meant to be — though perhaps we could have done without the Italian houseservant/blackmailer, regrettably named Guido). Generally speaking, you can believe this tale is taking place in the 1930s rather than a half-century earlier, unlike Carolyn Wells’ mysteries from the same decade.

Moreover, the clueing is respectable. And the murder means used in the five killings is…. Well, while it’s not original to Thayer (and John Rhode used it in a detective novel three years later, though only for a murder attempt late in the book), it’s kind of cute, in Golden Age Baroque fashion.

However, fatal weaknesses in The Scrimshaw Millions are its slack narrative, its sometimes careless writing and its lack of credible police procedure and scientific detail.

I have read the claim that the hugely prolific thriller writer Edgar Wallace, who boasted of being able to compose novels over weekends, in the course of one tale managed to change the name of his heroine (i.e., she starts off as Janet, say, and becomes Betty). Yet I had never come across such a phenomenon myself in an Edgar Wallace shocker, or, indeed, in a mystery tale by any other author — until I read Lee Thayer.

In The Scrimshaw Millions the secretary of that late, unlamented miser, Simon Scrimshaw, is introduced on page 51 as “Evangeline Osgood.” Yet five pages later her surname has changed to “Ogden.”

And there’s more! Although we are told for most of the tale that Simon’s two spinster sisters — thought at first to have died from heart failure–were both poisoned by “aconite” (I think “aconotine” was meant), late in the book the poison abruptly becomes arsenic.

All in all, I think it’s fair to say Lee Thayer was playing fast and loose with poisons, as well as with police procedure, in The Scrimshaw Millions. For no credible reason whatsover, three different poisons are used to slay in the tale, all by the same individual murderer: the alchemical aconite/aconotine/arsenic concoction, nicotine and cyanide (the last is later called hydrocyanic acid).

One might have thought this might have made the police suspicious of the character we are told works in a chemical factory, but, nope! It doesn’t seem to occur to anyone even to cock an eyebrow.

You might also think the murderer would have had to have been mad to adopt such an approach to attaining an inheritance. Well, hold on to your hats, it looks like he was:

“It’s too late now!” The exultant light of madness [shone in his eyes]. [p. 299]

Nearly forty years ago, Julian Symons labeled certain formerly quite popular and highly regarded detective novelists like John Rhode (a peudonym of Cecil John Charles Street) as “humdrums.” Other, more recent, mystery genre survey authors like P.D. James have followed suit, adopting Symons’ disparaging tone toward these writers.

Yet, compared to Lee Thayer, I say please, Lord, give me more “humdrums” like John Rhode. The use Rhode makes of science in his tales often is quite fascinating, ingenious, adroit and credible. In The Scrimshaw Millions none of those adjectives can be applied to Thayer’s (mis)use of science.

Traditionalist American mystery writers of the Golden Age of detection like Lee Thayer and Carolyn Wells often aped, as much they could, the form and milieu of detective novels of superior British counterparts.

Thayer, for example, clearly seems to have deliberately copied Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter/Bunter master-servant relationship with her own series detective, red-haired Peter Clancy, and his impeccable English manservant, Wiggar (the latter character was introduced by Thayer in 1929, ten years after she had debuted Clancy and six years after Sayers gave the world Lord Peter and Bunter). But Thayer and Wells are but pale shadows of far more substantial authors (and to be sure, there were many first-rate American traditionalists as well).

Still, the patented Lee Thayer cosmic retribution denouement so aptly described by Mike Nevins is impressive in its own loopy way. In The Scrimshaw Millions the entire house of the murdered miser falls in on the investigators and suspects just after the killer, pressed by the intrepid detective Peter Clancy, makes his mad confession:

The terrible cry of repudiation rang out in the desolate house, and as if the awful horror in it had terrible power there came a strange, wild shudder, a trembling through all the ancient walls, a hideous splitting crash, and the ceiling above their heads sagged downward, ripped across, and fell. [pp. 299-300]

Top that if you can, Agatha Christie and Hercule Poirot! Don’t tell me you’ve never wanted the roof to collapse on one of those drawing room lectures David Suchet gives in every darn one of his TV productions.

Providentially, one might say, only the mad murderer is killed when the house collapses in The Scrimshaw Millions. The nice boy lives to marry the nice girl, the policemen survive to continue getting murder cases all wrong, and Wiggar escapes the wreckage to continue happily serving his mildly concussed master Peter Clancy in many another perhaps-something-less-than-entirely-enthralling Lee Thayer mystery.

Wed 6 Oct 2010

100 Good Detective Novels

by Mike Grost

These are all real detective stories: tales in which a mystery is solved by a detective. Real detective fiction tends to go invisible in modern society, in which many people prefer crime fiction without mystery.

The list is in chronological order but unfortunately omits many major short story writers: G. K. Chesterton, Jacques Futrelle, H. C. Bailey, Edward D. Hoch, and other greats.

Émile Gaboriau, Le Crime d’Orcival (1866)

Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone (1868)

Israel Zangwill, The Big Bow Mystery (1891)

Anna Katherine Green, The Circular Study (1900)

Edgar Wallace, The Four Just Men (1905)

Cleveland Moffett, Through the Wall (1909)

John T. McIntyre, Ashton-Kirk, Investigator (1910)

R. Austin Freeman, The Eye of Osiris (1911)

E. C. Bentley, Trent’s Last Case (1913)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Valley of Fear (1914)

Clinton H. Stagg, Silver Sandals (1914)

Johnston McCulley, Who Killed William Drew? (1917)

Octavus Roy Cohen, Six Seconds of Darkness (1918)

Mary Roberts Rinehart & Avery Hopwood, The Bat (1920)

Donald McGibeny, 32 Caliber (1920)

Carolyn Wells, Raspberry Jam (1920)

Freeman Wills Crofts, The Cask (1920)

A. A. Milne, The Red House Mystery (1922)

G. D. H. Cole, The Brooklyn Murders (1923)

Carroll John Daly, The Snarl of the Beast (1927)

Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest (1927)

Horatio Winslow and Leslie Quirk, Into Thin Air (1929)

Samuel Spewack, Murder in the Gilded Cage (1929)

Thomas Kindon, Murder in the Moor (1929)

Mignon G. Eberhart, While the Patient Slept (1930)

Victor L. Whitechurch, Murder at the College / Murder at Exbridge (1932)

Ellery Queen, The Greek Coffin Mystery (1932)

Anthony Abbot, About the Murder of the Circus Queen (1932)

S. S. Van Dine, The Dragon Murder Case (1933)

Helen Reilly, McKee of Centre Street (1933)

Dermot Morrah, The Mummy Case (1933)

Dorothy L. Sayers, The Nine Tailors (1934)

Milton M. Propper, The Divorce Court Murder (1934)

John Dickson Carr, The Three Coffins / The Hollow Man (1935)

Georgette Heyer, Merely Murder / Death in the Stocks (1935)

David Frome, Mr. Pinkerton Has the Clue (1936)

Nigel Morland, The Case of the Rusted Room (1937)

Cyril Hare, Tenant for Death (1937)

Baynard Kendrick, The Whistling Hangman (1937)

Ngaio Marsh, Death in a White Tie (1938)

R. A. J. Walling, The Corpse With the Blue Cravat / The Coroner Doubts

(1938)

Dorothy Cameron Disney, Strawstacks / The Strawstack Murders (1938-1939)

Rex Stout, Some Buried Caesar (1938-1939)

Rufus King, Murder Masks Miami (1939)

Theodora Du Bois, Death Dines Out (1939)

Erle Stanley Gardner, The D.A. Draws a Circle (1939)

Agatha Christie, One Two, Buckle My Shoe / An Overdose of Death (1940)

J. J. Connington, The Four Defences (1940)

Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely (1940)

Frank Gruber, The Laughing Fox (1940)

Anthony Boucher, The Case of the Solid Key (1941)

Stuart Palmer, The Puzzle of the Happy Hooligan (1941)

Kelley Roos, The Frightened Stiff (1942)

Cornell Woolrich, Phantom Lady (1942)

Frances K. Judd, The Mansion of Secrets (1942)

Helen McCloy, The Goblin Market (1943)

Anne Nash, Said With Flowers (1943)

Mabel Seeley, Eleven Came Back (1943)

Norbert Davis, The Mouse in the Mountain (1943)

Robert Reeves, Cellini Smith: Detective (1943)

Hake Talbot, The Rim of the Pit (1944)

John Rhode, The Shadow on the Cliff / The Four-Ply Yarn (1944)

Allan Vaughan Elston & Maurice Beam, Murder by Mandate (1945)

Walter Gibson, Crime Over Casco (1946)

George Harmon Coxe, The Hollow Needle (1948)

Wade Miller, Fatal Step (1948)

Alan Green, What a Body! (1949)

Hal Clement, Needle (1949)

Bruno Fischer, The Angels Fell (1950)

Jack Iams, What Rhymes With Murder? (1950)

Richard Starnes, The Other Body in Grant’s Tomb (1951)

Richard Ellington, Exit for a Dame (1951)

Lawrence G. Blochman, Recipe For Homicide (1952)

Day Keene, Wake Up to Murder (1952)

Isaac Asimov, The Caves of Steel (1953)

Henry Winterfeld, Caius ist ein Dummkopf / Detectives in Togas (1953)

Craig Rice, My Kingdom For a Hearse (1956)

Frances and Richard Lockridge, Voyage into Violence (1956)

Harold Q. Masur, Tall, Dark and Deadly (1956)

James Warren, The Disappearing Corpse (1957)

Seicho Matsumoto, Ten to sen (Point and Lines) (1957)

Michael Avallone, The Crazy Mixed-Up Corpse (1957)

Ed Lacy, Shakedown for Murder (1958)

Lenore Glen Offord, Walking Shadow (1959)

Allen Richards, To Market, To Market (1961)

Christopher Bush, The Case of the Good Employer (1966)

Randall Garrett, Too Many Magicians (1967)

Michael Collins, A Dark Power (1968)

Merle Constiner, The Four from Gila Bend (1968)

Bill Pronzini, Undercurrent (1973)

Nicholas Meyer, The West End Horror (1976)

Thomas Chastain, Vital Statistics (1977)

William L. DeAndrea, Killed in the Ratings (1978)

Clifford B. Hicks, Alvin Fernald, TV Anchorman (1980)

Donald J. Sobol, Angie’s First Case (1981)

Kyotaro Nishimura, Misuteri ressha ga kieta (The Mystery Train

Disappears) (1982)

K. K. Beck, Murder in a Mummy Case (1986)

Jon L. Breen, Touch of the Past (1988)

Stephen Paul Cohen, Island of Steel (1988)

Earl W. Emerson, Black Hearts and Slow Dancing (1988)

Editorial Comment: This will do it for today, but I do have one more list to post. David Vineyard sent it to me this morning. It’s a followup to his previous list, consisting of what he calls “100 Important Books From Before the Golden Age.” The cutoff date for these is 1913, which is where his earlier list began. While not all of the books on this new list may be crime fiction, they’re all important to the field. Look for it soon!

Sun 4 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

HULBERT FOOTNER – Sinfully Rich. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1940. Reprinted as a Philadelphia Inquirer “Gold Seal Novel”: August 3, 1941. Hardcover reprint: Books Inc., 1944. British edition: Collins Crime Club, hc, 1940.

Hulbert Footner was a Canadian-American writer who, nearing the age of forty, began publishing mystery tales about the time World War One ended.

He soon made a good name for himself in the field, particularly with his tales of an early female detective, Madame Rosika Storey. (Madame Storey is who he is remembered for today, when he is remembered.)

Many of his novels and stories are more accurately characterized as thrillers; and even his tales of putative detection seem more “mystery” than detection, with the author not paying scrupulous attention to the fair play concept (allowing the reader the chance to solve the mystery for him/herself through deciphering clues fairly provided by the author).

Still, Footner’s works often have “zip” and are entertaining enough, just not necessarily mentally over-rigorous. A good example of his style is one of his later works, Sinfully Rich (1940).

In Sinfully Rich, a sixty-seven year old millionaire’s widow who has been living it up in New York City smart society after the death of her tightfisted husband is found dead after a big night, all her jewels missing.

The police and medical examiners think she died naturally and then was robbed, but ace journalist Mike Speedon (who is to inherit a modest sum of $100,000 dollars from the “old dame”) shows the experts what for (journalists — what don’t they know?). He proves the millionairess was murdered (disappointingly so, as the putatively amazing murder method is taken lock, stock and barrel from Dorothy L. Sayers and Unnatural Death, published a dozen years earlier).

In the classical British manner there is are two wills, a missing nephew, a dubious lawyer, a scheming gigolo and household full of suspicious employees and servants (personal secretary, personal maid, first housemaid, butler and “second man”).

What more could a mystery fan ask for? Well, a more clever plot, perhaps, but maybe that is being uncharitable on my part. There were many, many mystery novels published in those days, and one cannot reasonably expect sheer brilliance from all of them.

What is most enjoyable about the book is the interactions of the characters up to the resolution of the mystery. Footner casts a wryly amused glance over the foibles of the wealthy, who have, seemingly, a great deal of time and money to burn.

Footner treats his readers to glimpses of the high life, US version, but he also encourages them to mock what they see, through the focal character of the cynical, clever, manly reporter, such a classic figure in American film and literature from this period. If it’s rather like a watered-down Dashiell Hammett highball (The Thinner Man, say), at least it goes down smoothly, with no unpleasant aftertaste.

There is investigation, but no really satisfying ratiocinative process. (I was rather reminded in this respect of the British novelist J. S. Fletcher, whose mystery novels probably were more popular during the Golden Age in the United States than they were in his native Britain.)

Because there really isn’t fair play, Footner is able to maintain until the end of the novel suspense concerning the question “Whodunit?”; yet some of the fun, for me anyway, is lost.

If, as Robert Frost opined, free verse is like playing tennis without a net, so is a mystery that does not practice fair play. You can still enjoy it, but you feel a bit cheated! Still, I’ve read far worse mysteries from the period than Sinfully Rich. (See my Carolyn Wells reviews!)

Editorial Comment: A list of the “Gold Seal” novels published in the Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer (mid-1930s to late 1940s) can be found online here. Many of them were mysteries; others appear to be straight romances.

Tue 29 Jun 2010

Serials from ARGOSY published as books

by Denny Lien.

Nobody [has] mentioned having seen this data reprinted anywhere, and it seemed too interesting to leave unreprinted. So I managed to obtain photocopies of both lists [as published in ARGOSY] and have transcribed the information below. I did change format (using a slash rather than ellipses to separate author and title, using ibid rather than ditto marks, and in the case of the first list moving the asterisk indicators from before title to after title) but did not make any corrections to the actual authors and titles as listed.

Though I’ll note here that The Single Track appears both as by “Grant Douglas” and “Douglas Grant” — the latter is correct, though in any case this was a pseudonym for Isabel Ostrander.) I also noted after the fact that my original statement that the first list did not include work from GOLDEN ARGOSY was incorrect.

While the lists speak of “serials,” I notice a few examples where the books were actually derived from story collections or from complete-in-one-issue novels (most obviously Tarzan of the Apes). The asterisk codes in the first list, indicating the book was then in print, were not used in the second.

— Denny Lien / U of Minnesota Libraries. [This compilation first appeared on the FictionMags Yahoo list.]

From the December 30, 1933 “Argonotes,” pp. 140-144

**********

410 ARGOSY BOOKS

At least four hundred ten serials which appeared in ARGOSY, ARGOSY-ALLSTORY, and ALLSTORY were later published in book form. Probably many more have not yet been included, and can be added later to this list which includes several we had not previously announced.

Of the following tales, those with two asterisks (**) are known to be still available in the $2.00 editions in this category; those with one asterisk (*) are available in the 75 cent editions.

ARGOSY AND ARGOSY ALLSTORY

Achmed Abdullah / The Man on Horseback

ibid / The Trail of the Beast

ibid / The Mating of the Blades *

Eustace L. Adams / Gambler’s Throw

Stookie Allen / Men of Daring (50 cents) *

Larry Barretto / To Babylon *

H. Bedford-Jones / The Gate of Farewell

ibid / John Solomon, Super-Cargo

ibid / Cyrano

ibid / The King’s Pardon **

Jack Bechdolt / South of Fifty-Three

Max Brand / The Guide to Happiness

ibid / Gun Gentlemen

ibid / Senor Jingle Bells *

ibid / His Third Master

ibid / Kain

ibid / The Stranger at the Gate

ibid / Tiger

ibid / Black Jack

ibid / The Garden of Eden

ibid / The Night Horseman *

ibid / The Seventh Man *

ibid / Dan Barry’s Daughter *

ibid / The Longhorn Feud **

George J. Brent / Voices

Loring Brent / Peter the Brazen

ibid / No More a Corpse **

John Buchan / The Three Hostages

Charles Neville Buck / Flight in the Hills

ibid / A Gentleman in Pajamas

Edgar Rice Burroughs / The Chessmen of Mars *

ibid / Tarzan the Terrible *

ibid / Tarzan and the Golden Lion *

ibid / Tarzan and the Ant Men *

ibid / The Bandit of Hell’s Bend *

ibid / The Moon Maid *

ibid / The War Chief *

ibid / Apache Devil **

ibid / Tarzan and the City of Gold **

Evelyn Campbell / The Knight of Lonely Land

Stanley Hart Cauffman / The Ghost of Gallows Hill

Robert Orr Chipperfield / Above Suspicion

ibid / Bright Lights

Arthur Hunt Chute / Far Gold

John Boyd Clarke / Findings Is Keepings

Frank Condon and Charlton R. Edholm / The Dancing Doll

Courtney Ryley Cooper / Caged

S.R. Crockett / Hal o’ the Ironsides

Ray Cummings / The Sea Girl

ibid / The Man Who Mastered Time *

Captain A.E. Dingle / Gold Out of Celebes

E. and J. Dorrance / Flames of the Blue Ridge

Grant Douglas / The Single Track

H.S. Drago and Joseph Noel / Whispering Sage

Harry Sinclair Drago / Following the Grass

ibid / The Snow Patrol

ibid / Smoke of the .45

ibid / Out of the Silent North

J. Allen Dunn / The Death Gamble

J. Breckenridge Ellis / The Picture on the Wall

Laurie York Erskine / The Confidence Man *

ibid / The Coming of Cosgrove *

ibid / The Laughing Rider *

ibid / Valor of the Range *

Hulbert Footner / A Self-Made Thief *

ibid / Officer!

ibid / Gentlman Roger’s Girl

ibid / The Velvet Hand *

ibid / Queen of Clubs *

ibid / Madame Storey

ibid / The Under Dogs *

ibid / The Doctor Who Held Hands *

ibid / Easy to Kill *

W. Bert Foster / From Six to Six *

David Fox / The Doom Dealer

ibid / The Handwriting on the Wall

ibid / Ethel Opens the Door

Edgar Franklin / White Collars

W.A. Fraser / Caste

Oscar J. Friend / Click of the Triangle T *

ibid / The Mississippi Hawk *

ibid / The Range Maverick *

Sinclair Gluck / Red Emeralds

John Goodwin / The Sign of the Serpent

Douglas Grant / Two-Gun Sue *

ibid / The Single Track

ibid / The Fifth Ace

ibid / Booty

Zane Grey / The Rainbox Trail *

ibid / The Lone Star Ranger *

Augusta Groner and Grace Isabel Colbron / The Lady in Blue

Katherine Haviland-Taylor / Yellow Soap

Arthur Preston Hankins / Cavern Gold

James B. Hendryx / Prairie Flower

ibid / Without Gloves *

ibid / Snowdrift *

John Holden / Prairie Shock *

Rupert Sargent Holland / The Mystery of the Opal

Fred Jackson / The Third Act

George M. Johnson / The Gun-Slinger

ibid / Squatter’s Rights *

ibid / Trouble Ranch

ibid / Riders of the Trail *

ibid / Jerry Rides the Range **

ibid / Tickets to Paradise **

ibid / Spyglass Range **

Rufus King / North Star *

Otis Adelbert Kline / The Planet of Peril

ibid / Maza of the Moon

ibid / The Prince of Peril

Slater LaMaster / The Phantom in the Rainbow

Harold Lamb / Marching Sands

A.T. Locke / Hell Bent Harrison *

Francis Lynde / David Vallory

Fred MacIsaac / The Vanishing Professor

ibid / The Hole in the Wall

ibid / The Mental Marvel

F.v.W. Mason / Captain Nemesis **

Johnston McCulley / The Mark of Zorro

ibid / The Further Adventures of Zorro

Lyon Mearson / The Whisper on the Stair

A. Merritt / The Ship of Ishtar

ibid / Seven Footprints to Satan

ibid / The Face in the Abyss

ibid / The Dwellers in the Mirage **

ibid / Burn, Witch, Burn! **

Mulford, Clarence E. / Hopalong Cassidy Returns *

ibid / Hopalong Cassidy’s Protege *

Talbot Mundy / Ho! for London Town

ibid / When Trails Were New

George Washington Ogden / Claim Number One

ibid / Trail’s End

ibid / The Duke of Chimney Butte

ibid / The Flockmaster of Poison Creek

ibid / A Man from the Badlands **

Frederic Ormond / The Three Keys

Isabel Ostrander / McCarthy Incog *

ibid / Dust to Dust *

ibid / Annihilation *

ibid / How Many Cards

ibid / Mathematics of Guilt

ibid / Liberation

Frank L. Packard / Pawned *

ibid / The Four Stragglers *

ibid / The Locked Book *

ibid / The Big Shot *

ibid / The Gold Skull Murders *

ibid / The Hidden Door **

ibid / The Purple Ball **

Lawrence Perry / Holton of the Navy

Kenneth Perkins / Strange Treasure

ibid / The Beloved Brute

ibid / The Gun Fanner

ibid / Gold *

ibid / Voodoo’d *

ibid / The Moccasin Murders *

ibid / The Canon of Light *

ibid / Ride Him, Cowboy *

ibid / The Discard

ibid / Starlit Trail

ibid / Wild Paradise

E.J. Rath / Mr. 44

ibid / Sam

ibid / The Nervous Wreck

Victor Rousseau / Wooden Spoil

ibid / The Big Muskeg

John Schoolcraft / The Bird of Passage

Charles Alden Seltzer / Lonesome Ranch *

ibid / The Trail Horde *

ibid / The Vengeance of Jefferson Gawne *

ibid / The Ranchman *

ibid / Beau Rand *

ibid / Drag Harlan *

ibid / Square Deal Sanderson *

ibid / The Way of the Buffalo *

ibid / Channing Comes Through *

ibid / Brass Commandments *

ibid / The Gentleman from Virginia *

ibid / Last Hope Ranch *

ibid / The Valley of the Stars *

ibid / Land of the Free *

ibid / Mystery Range *

ibid / The Mesa *

ibid / The Raider *

ibid / The Red Brand *

ibid / Gone North *

ibid / Double Cross Ranch *

ibid / War on Wishbone Range **

ibid / Clear the Trail **

George C. Shedd / The Invisible Enemy

ibid / In the Shadow of the Hills

Perley Poore Sheehan / Apache Gold

Garret Smith / I Did It *

Raymond S. Spears / The Flying Coyotes *

Louis Lacy Stevenson / Big Game

Charles B. Stilson / A Cavalier of Navarre

ibid / The Ace of Blades

T.S. Stribling / East is East

ibid / Blackwater

Albert Payson Terhune / Black Wings

ibid / Blundell’s Last Guest *

Lee Thayer / That Affair at “The Cedars”

Louis Tracy / The Passing of Charles lanson

W.C. Tuttle / The Silver Bar Mystery **

Stanley Waterloo / A Son of the Ages

Don Waters / The Call of Shining Steel *

ibid / Pounding the Rails *

Carolyn Wells / The Vanishing of Betty Varian

ibid / The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

ibid / More Lives Than One

ibid / The Bronze Hand

William Patterson White / The Buster *

Frank Williams / The Harbor of Doubt

George F. Worts / The Silver Fang

ibid / Who Dares *

ibid / The Blacksander *

ibid / Red Darkness

ibid / The Haunted Yacht Club

ALLSTORY AND ALLSTORY-CAVALIER

Achmed Abdullah / The Blue-Eyed Mandarin

ibid / Bucking the Tiger

ibid / Night Drums *

ibid / The Red Stain

ibid / Wings

Robert Aitken / The Golden Horseshoe

John Charles Beecham / The Argus Pheasant

Leslie Burton Blades / Claire

Earl Wayland Bowman / The Ramblin’ Kid

Cyris Townsend Brady / Britton of the Seventh

ibid / The Eagle of the Empire

ibid / The Patriots

Max Brand / Trailin’ *

ibid / The Untamed *

John Buchan / Salute to Adventurers *

ibid / The Thirty-Nine Steps

Charles Neville Buck / Destiny

ibid / When Bercat Went Dry

Edgar Rice Burroughs / The Beasts of Tarzan *

ibid / The Gods of Mars *

ibid / The Mucker *

ibid / A Princess of Mars *

ibid / The Son of Tarzan *

ibid / Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar *

ibid / Tarzan of the Apes *

ibid / Tarzan the Untamed *

ibid / Thuvia, Maid of Mars *

ibid / The Warlord of Mars *

ibid / Pellucidar *

ibid / The Mad King *

ibid / The Eternal Lover *

ibid / The Cave Girl *

ibid / At the Earth’s Core *

ibid / The Monster Men *

Octavus Roy Cohen / The Crimson Alibi

ibid / Gray Dusk

Will Levington Comfort / The Yellow Lord

Ridgwell Cullum / The Way of the Strong

Ray Cummings / The Girl in the Golden Atom

Charles Belmont Davis / Nothing a Year

George Dilnot / Suspected

Ethel and James Dorrance / Glory Rides the Range

George Allan England / The Alibi

ibid / Cursed

ibid / The Flying Legion

ibid / Pod, Bender & Co.

Jacob Fisher / The Quitter

A.H. Fitch / The Breath of the Dragon

Hulbert Footner / The Deaves Affair

ibid / The Fur Bringers

ibid / The Owl Taxi

ibid / The Huntress

ibid / The Sealed Valley

ibid / The Substitute Millionaire

ibid / The Woman from Outside

ibid / On Swan River

ibid / The Fugitive Sleuth

ibid / The Chase of the Linda Belle

David Fox / The Shadowers

Edgar Franklin / In and Out

ibid / Comeback

Arnold Fredericks / The Film of Fear

R. Austin Freeman / A Silent Witness *

Allen French / Hiding Places

Frank Froest / The Maelstrom

J.U. Giesy / Mimi

George Gilbert / Midnight of the Ranges

Jackson Gregory / The Joyous Troublemaker

ibid / Ladyfingers

ibid / The Short Cut

ibid / Six Feet Four

ibid / Wolf Breed

Zane Grey / The Border Legion *

Thomas W. Hanshew / The Riddle of the Night

Horace Hazeltine / The City of Encounters

James B. Hendryx / The Gold Girl

ibid / The Gun-Brand

ibid / The Promise

ibid / The Texan *

C.C. Hotchkins / Maude Baxter

ibid / The Red Paper

Eleanor Ingram / A Man’s Hearth

Jeremy Lane / Yellow Men Asleep

Henry Leverage / Where Dead Men Walk

Natalie Sumner Lincoln / The Moving Finger

ibid / The Red Seal

Francis Lynde / Branded

Johnson McCulley / Broadway Bab

ibid / Captain Fly-by-Night

Everett MacDonald / The Red Debt

Grace Sartwell Mason / The Golden Hope

E.K. Means / E.K. Means

ibid / More E.K. Means

ibid / Further E.K. Means

A. Merritt / The Moon Pool

Philip Verrill Mighels / Hearts of Grace

George Washington Ogden / The Rustler of Wind River

ibid / Steamboat Gold *

E. Phillips Oppenheim / The Curious Quest *

William Hamilton Osborne / The Catspaw

Isabel Ostrander / Ashes to Ashes

ibid / The Clue in the Air

ibid / Suspense

ibid / The Twenty-Six Clues

Frank L. Packard / The Beloved Traitor

ibid / From Now On *

ibid / The Sin That Was His

Randall Parrish / Comrades of Peril

ibid / Contraband

ibid / The Devil’s Own

ibid / The Strange Case of Cavendish

William MacLeod Raine / The Big Town Roundup

ibid / The Sheriff’s Son

E.J. Rath / Too Many Crooks

ibid / Too Much Efficiency

Mary Roberts Rinehart / The Circular Staircase *

ibid / The Man in Lower Ten *

C.A. Robbins / The Unholy Three

Charles G.D. Roberts / Jim

Lee Robinet / The Forest Maiden

C. MacLean Savage / The Turn of the Sword

John Reed Scott / The Man in Evening Clothes

Garrett P. Serviss / A Columbus of Space

Perley Poore Sheehan / The House With a Bad Name

ibid / If You Believe It, It’s So

ibid / The Passport Invisible

ibid / Those Who Walk in Darkness

Perley Poore Sheehan and Robert H. Davis / We Are French!

Robert Simpson / The Bite of Benin

ibid / Swamp Breath

Martha M. Stanley / The Souls of Men

Jack Steele / The House of Iron Men

Elizabeth Sutton / Dead Fingers

Albert Payson Terhune / Dad

ibid / The Unlatched Door

Harold Titus / Bruce of the Circle A

ibid / I Conquered

Louis Tracy / His Unknown Wife

Varick Vanardy / The Lady of the Night Wind

ibid / Something Doing

ibid / The Two-Faced Man

Louis Joseph Vance / The Black Bag

ibid / The Bronze Bell

Charles Edmonds Walk / The Paternoster Ruby

Ann Warner / The Tigress

Carolyn Wells / The Curved Blades

ibid / Faulkner’s Folly

ibid / Vicky Van

ibid / Raspberry Jam

Frank Williams / The Harbor of Doubt

C.N. and A.M. Williamson / Everyman’s Land

ibid / A Soldier of the Legion

ARGOSY AND GOLDEN ARGOSY (Juvenile)

Horatio Alger, Jr. / Do and Dare

ibid / Hector’s Inheritance

ibid / The Store Boy

ibid / work and Win

ibid / Helping Himself

ibid / Facing the World

ibid / In a New World

ibid / Struggling Upward

ibid / Bob Burton

ibid / The Young Acrobat

ibid / Dean Dunham

ibid / Luke Walton

ibid / Five Hundred Dollars

ibid / Driven from Home

ibid / The Erie Train Boy

ibid / Tom Turner’s Legacy

ibid / Walter Sherwood’s Probation

ibid / Digging for Gold

ibid / Debt of Honor

ibid / Jed

ibid / Chester Rand

ibid / Lester’s Luck

ibid / Rupert’s Ambition

ibid / The Young Salesman

ibid / Andy Grant’s Pluck

ibid / A Cousin’s Conspiracy

George H. Coomer / Boys in the Forecastle

Edward S. Ellis / Arthur Helmuth

ibid / Check No. 2134

G.A. Henty / Facing Peril

Frank A. Munsey / A Tragedy of Errors

ibid / The Boy Broker

ibid / Under Fire

ibid / Afloat in a Great City

ibid / Harry’s Scheme

Matthew White, Jr. / Eric Dane

ibid / The Adventures of a Young Athlete

ibid / My Mysterious Fortune

ibid / The Young Editor

ibid / The Tour of a Private Car

ibid / Guy Hammersley

**********************

**********************

From the June 23, 1934 “Argonotes, ” pp. 141-144

*********************

660

Thanks to the cooperation of readers Dale Morgan, R.L. Rocklin, and Julius Schwartz, and by further search of our own records, we have located more books from ARGOSY serials.

From ARGOSY alone, at least 368 books have been made. And in the other half of the ARGOSY–ALLSTORY WEEKLY — ALLSTORY — there were 195 books. For the first time we have made a list of CAVALIER books before its merger with ALLSTORY — 76 books, plus eight more in OCEAN and SCRAP BOOK which were merged with it. And there were 13 books from RAILROAD MAN’S MAGAZINE, merged with ARGOSY. 563 books from ARGOSY and ALLSTORY alone — and a grand total of 660 books serialized in the magazines which made up to-day’s ARGOSY!

Six hundred and sixty books since ARGOSY was founded in 1882. We’d be surprised if any other magazine can come within several hundreds of that total. And ARGOSY goes on — we know of several recent serials now on the book publishers’ presses, soon to be announced.

The following books were not included in the 410 listed Dec. 30 (a list which included several duplications and errors, all cancelled in totaling our 660):

ARGOSY

Frank Aubrey / A Queen of Atlantis

Edwin Baird / The Heart of Virginia Keep

Richard Barry / The Big Gun

Nalbro Bartley / The Whistling Girl

St. Clair Beall / The Winning of Sarenne

H. Bedford-Jones / The Seal of John Solomon

Arnold Bennett / The Grand Babylonian Hotel

Robert Ames Bennet / Sunnie of Timberline

Max Brand / The Sword Lover

Edgar Rice Burroughs / Pirates of Venus

H.D. Chetwode / John of Strathbourne

William Wallace Cook / The Fateful Seventh

ibid / The Eighth Wonder

ibid / The Desert Argonaut

ibid / The Sheriff of Broken Bow

ibid / An Innocent Outlaw

ibid / Jim Dexter, Cattleman

ibid / The Gold Gleaners

ibid / In the Wake of the Simitar

ibid / A Round Trip to the Year 2000

ibid / Cast Away at the Pole

ibid / Adrift in the Unknown

ibid / Marooned in 1492

ibid / The Cats-Paw

ibid / At Daggers Drawn

ibid / Rogers of Butte

ibid / The Spur of Necessity

W. Carleton Daws / The Voyage of the Pulo Way

Burford Delanncy / The Midnight Special

J. Allan Dunn / The Isle of Drums

ibid / A Man to His Mate

ibid / Fortune Unawares

Knarf Elivas / John Ship, Mariner

J.S. Fletcher / The Double Chance

Edgar Franklin / Mr. Hawkins’ Humorous Adventures

John Frederick / Luck

ibid / Pride of Tyson

Thomas Griffiths and Armstrong Livingston / The Ju-Ju Man

John H. Hamlin / Range Rivals

Donald Bayne Hobart / The Whistling Waddy

J.M. Hoffman / Six-Foot Lightning

Fred Jackson / The Diamond Necklace

George M. Johnson / Texas Range Rider

Rufus King / Whelp of the Winds

William Le Quieux / An Eye for an Eye

Henry Leverage / The Purple Limited

Will Levinrew / The Poison Plague

Fred MacIssac / Burnt Money

Arthur W. Marchmont / When I Was Czar

ibid / By Right of Sword

ibid / A Dash for a Throne

Edison Marshall / The Tiger Trail

Wyndham Martyn / The Mysterious Mr. Garland

William Stevens McNutt / The Endless Chain

Elizabeth York Miller / The Greatest Gamble

William D. Moffat / The Crimson Banner

ibid / Not Without Honor

Sinclair Murray ./ The Crucible

George Washington Ogden / The Ghost Road

ibid / The Trail Rider

ibid / The Well Shooters

John Oxenham / God’s Prisoner

Max Pemberton / The Phantom Army

Kenneth Perkins / Fast Trailin’

ibid / The Devil’s Saddle

Frank Lillie Pollock / Frozen Fortune

William MacLeod Raine / Steve Yeager

ibid / Moran Beats Back

E.J. Rath / Gas–Drive In

John P. Ritter / The Man Who Dared

Victor Rousseau / The Big Man of Bonne Chance

ibid / The Golden Horde

ibid / My Lady of the Nile

ibid / Mrs. Aladdin

Edwin L. Sabin / The Rose of Santa Fe

Frank Savile / Beyond the Great South Wall

F.K. Scribner / The Secret of Frontellac

Charles Alden Seltzer / Slow Burgess

ibid / Trailing Back

Garrett P. Serviss / The Moon Maiden

Perley Poore Sheehan / Three Sevens

Garret Smith / Between Worlds

Georges Surdez / Swords of the Soudan

W.C. Tuttle / Bluffer’s Luck

C.C. Waddell / Midnight to High Noon

Frank Williams / The Wilderness Trail

ARGOSY (Juveniles)

Harry Castlemon / Don Gordon’s Shooting Box

Edward S. Ellis / The Last Trail

ibid / Campfire and Wigwam

ibid / Footprints in the Forest

ibid / The Camp in the Mountains

ibid / The Last War Trail

ibid / Red Eagle

ibid / Blazing Arrow

W. Bert Foster / In Alaskan Waters

ibid / Arthur Blaisdell’s Choices

ibid / A Lost Expedition

ibid / The Treasure of South Lake Farm

ibid / The Quest of the Silver Swan

William Murray Graydon / With Cossack and Convict

Oliver Optic / Making a Man of Himself

ibid / Every Inch a Boy

ibid / Always in Luck

ibid / The Young Pilot

ibid / The Cruise of the Dandy

ibid / The Young Hermit

ibid / The Prisoners of the Cave

ibid / Among the Missing

Edward Stratemeyer / Reuben Stone’s Discovery

ibid / True to Himself

ibid / Richard Dare’s Venture

ALL-STORY (Merged with ARGOSY as THE ARGOSY ALL-STORY WEEKLY)

Achmed Abdullah / A Buccaneer in Spats

ibid / The Honourable Gentleman and Others

Achmed Abdullah, Max Brand, E.R. Means, and P.P. Sheehan / The Ten-Foot Chain

Edwin Baird / The City of Purple Dreams

H. Bedford-Jones / Loot

ibid / A Three-Fold Cord

John Charles Beechams / The Yellow Spider

Max Brand / The Children of Night

ibid / Clung

ibid / Who Am I?

ibid / Fate’s Honeymoon

J. Storer Clouston / Two’s Two

William Wallace Cook / Thorndyke of the Bonita

ibid / Back from Bedlam

ibid / The Deserter

ibid / The Last Dollar

ibid / In the Web

ibid / The Goal of a Million

Capt. A.e. Dingle / The Island Woman

ibid / The Pirate Woman

Maurice Drake / The Ocean Sleuth

J.S. Fletcher / The Diamonds

Juliette Gordon-Smith / The Wednesday Wife

James B. Hendryx / The One Big Thing

Headon Hill / Sir Vincent’s Patient

Henry Leverage / The White Cipher

Frederick Ferdiand Moore / Sailor Girl

George Washington Ogden / The Bondboy

William MacLeod Raine / A Daughter of the Dons

E.J. Rath / The Brat

ibid / A Good Indian

ibid / Elope if You Must

ibid / Good References

ibid / Once Again

ibid / When the Devil Was Sick

C.A. Robbins / Silent, White, and Beautiful

Victor Rousseau / Jacqueline of Golden River

ibid / The Lion’s Jaws

ibid / Draft of Eternity

ibid / The Big Malopo

ibid / The Sea Demons

Perley Poore Sheehan / The Bayou Shrine

ibid / The Whispering Chorus

August Weissl / The Mystery of the Green Car

C.N. & A.M. Williamson / This Woman to This Man

CAVALIER (Merged with ALL-STORY as ALL-STORY-CAVALIER)

Frank R. Adams / Five Fridays

Arthur Applin / The Girl Who Saved His Honor

Robert Barr / Cardillac

Arnold Bennett / Hugo

Cyrus Townsend Brady / The Sword Hand of Napoleon

Victor Bridges / Another Man’s Shoes

Edgar Beecher Bronson / The Vanguard

Charles Neville Buck / The Portal of Dreams

ibid / The Call of the Cumberlands

Stephen Chambers / When Love Calls Men to Arms

Dane Coolidge / The Fighting Fool

F. Marion Crawford / The Undesirable Governess

Florence Crewe-Jones / The Inner Man

ibid / The Red Nights of Paris

James Oliver Curwood / Flower of the North

ibid / Isabel

Beulah Marie Dix / The Fighting Blade

Maurice Drake / The Salving of a Derelict

James Francis Dwyer / The White Waterfall

ibid / The Spotted Panther

George Allan England / The Golden Blight

ibid / Darkness and Dawn

Jacob Fisher / The Cradle of the Deep

Herbert Flowerdew / The Villa Mystery

Hulbert Footner / Jack Chanty

Arnold Fredericks / One Million Francs

ibid / The Ivory Snuff Box

ibid / The Blue Lights

ibid / The Little Fortune

Tom Gallon / As He Was Born

J.U. Giesy/ All for His Country

Rufus Gillmore / The Alster Case

John Goodwin / Without Mercy

Jackson Gregory / Under Handicap

ibid / The Outlaw

H. Rider Haggard / Morning Star

Forrest Halsey / The Stain

Horace Hazeltine / The Snapdragon

James B. Hendryx / Marquard the Silent

Maurice Hewlett / Brazenhead the Great

Fred Jackson / The Gripful of Trouble

Elizabeth Kent / Who?

William Le Queux / The Room of Secrets

James Locke / The Stem of the Crimson Dahlia

ibid / The Plotting of Frances Ware

Caroline Lockhart / The Full of the Moon

Harold McGrath / Pidgin Island

William Brown Maloney / The Girl of the Golden Gate

Philip Verrill Mighels / As It Was in the Beginning

Edward Bredinger Mitchell / The Shadow of the Crescent

Frederick Ferdinand Moore / The Devil’s Admiral

E. Phillips Oppenheim / Mr. Marx’s Secret

Isabel Ostrander (Lamb) / The Heritage of Cain

ibid / At 1:30

Frank L. Packard / Greater Love Hath No Man

William McLeod Raine / The Pirate of Panama

E.J. Rath / Something for Nothing

ibid / The Mantle of Silence

ibid / The Sky’s the Limit

Mary Roberts Rinehart / Where There’s a Will

Theodore Goodridge Roberts / Two Shall Be Born

ibid / Jess of the River

E. Serao / King of the Camorra

Garrett P. Serviss / The Second Deluge

Ralph Stock / Marama

Arthur Stringer / The Shadow

Alice Stuyvesant / The Hidden House

Louis Tracy / One Wonderful Night

Varick Vanardy / Alias the Night Wind

ibid / The Night Wind’s Promise

ibid / The Return of the Night Wind

Louis Joseph Vance / The Destroying Angel

ibid / The Day of Days

Henry Kitchell Webster / The Ghost Girl

John Fleming Wilson / The Princess of Sorry Valley

SCRAP BOOK and OCEAN (Merged with CAVALIER)

Robert Ames Bennet / Into the Primitive

Stephen Chalmers / A Prince of Romance

ibid / The Vanishing Smuggler

William Wallace Cook / Fools for Luck

ibid / A Deep Sea Game

ibid / Frisbie of San Antone

Albert Dorrington / The Radium Terrors

Crittendon Marriott / Isle of Dead Ships

RAILROAD MAN’S MAGAZINE (Merged with ARGOSY)

Harold Bindloss / By Right of Purchase

Max Brand / Harrigan

William Wallace Cook / Running the Signal

ibid / The Paymaster’s Special

ibid / Dare, of Darling & Co.

ibid / Trailing the Josephine

Emmet F. Harte / Honk and Horace

Johnston McCulley / A White Man’s Chance

Bannister Merwin / The Girl and the Hill

Randall Parrish / The Highway of Adventure

E.J. Rath / Let’s Go (Sixth Speed)

Victor Rousseau / Eric of the Strong Heart

Louis Joseph Vance / The Brass Bowl