Search Results for 'Francis M. Nevins'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 11 Dec 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

REVIEWED BY MIKE NEVINS:

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER – The Case of the Reluctant Model. Perry Mason #66. Morrow, hardcover, 1962. Pocket 4524, paperback, 1963. Reprinted many times since.

Fast, complex and unputdownable are the words for this one, which starts out unusually with Mason masterminding the strategy in a civil suit for slander that revolves around the authenticity of a certain painting.. There are some excellent character sketches, especially the aging playboy-businessman who dabbles at being a patron of the arts, and some knowledgeable insights on how to try lawsuits in the newspapers.

Eventually of course comes the standard pattern — the murder, the arrest of Mason’s client — the trial, the cross-examination scenes are among the most exciting in Gardner’s late books, and only the logical lapses and baseless deductions in Mason’s solution keep this one from ranking among Gardner’s best.

– This review first appeared in The MYSTERY FANcier, January 1977 (Vol. 1, No. 1)

Wed 16 Nov 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY MIKE NEVINS:

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER – The Case of the Bigamous Spouse. Perry Mason #65. Morrow, hardcover, 1961. Pocket, paperback, 1963. Many later printings and editions exist.

Here is one of the smoothest Masons of ESG’s last years, with a beautifully mounted plot, tremendous pace and a variety of sharp comments on everything from sales technique and modern marriage to police lawlessness and the· undertaking business.

Mason’s client is a gorgeous book saleswoman who has accidentally discovered that her best friend’s husband is a bigamist — and that he’s ready to kill her to keep his secret. When the bigamist is murdered instead, all hell breaks loose.

There are a few tiny plot flaws, and the solution is rabbit-out-of-a-hat, but still and all it’s a gorgeous entertainment reminiscent of Gardner’s prime.

– This review first appeared in The MYSTERY FANcier, January 1977 (Vol. 1, No. 1)

Thu 27 Oct 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY MIKE NEVINS:

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER – The Case of the Spurious Spinster. Perry Mason #64. William Morrow, hardcover, 1961. Pocket #4515, paperback, 1963. Reprinted many times since.

This was one of Anthony Boucher’s favorite late Masons, but I found little to praise in it except for Gardner’s never-failing story-telling pace and drive.

The plot has to do with corporation intrigue over a non-productive mine, a shoebox full of dubious cash, the impersonation of the company’s irascible female owner and, as if you hadn’t guessed, a murder.

But all the story elements remain chaotic and incredible by the fadeout, and even the courtroom sequence is weak, with Mason given little chance to shine. Gardner must have dictated this adventure on an off day.

– This review first appeared in The MYSTERY FANcier, January 1977 (Vol. 1, No. 1)

Fri 21 Oct 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY MIKE NEVINS:

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER – The Case of the Shapely Shadow. Perry Mason #63. William Morrow, hardcover, 1960. Pocket 4507, paperback, 1962. Ballantine, paperback, 1982. Reprinted many times.

There are a number of intriguing elements in this Perry Mason novel from Gardner’s final period, but like so many other late Masons, the finished product is a mess.

\

The story begins when a beautiful secretary who deliberately makes her-self look unattractive dumps a suitcase full of twenty do1lar bills and an ethical problem in the lawyer’s lap, thereby entangling him in the murder of her boss and the machinations of the three women in the corpse’s life.

The background material on railroad-station lockers and Mason’s savage courtroom deflation of a hostile medical witness are beautifully handled, but there are countless logical holes left unplugged, the motivation becomes ludicrous at crucial points, the plot depends on a chain of multiple coincidences,and the Least Likely Suspect is about as obvious as a leper in a nudist camp.

– This review first appeared in The MYSTERY FANcier, January 1977 (Vol. 1, No. 1)

Thu 10 Nov 2016

FRANCIS M. NEVINS, JR. – Corrupt and Ensnare. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hardcover, 1978. iUniverse, softcover, 2000. Ramble House, softcover, 2013.

Deeply involved in lawyer-detective Loren Mensing’s second mystery adventure are a contested will, a multi-million-dollar corporation with a history of working hand-in-glove with the CIA, and the not yet extinguished brand of ultra-liberalism left over from the 1960’s. It begins with a shoe-box full of money found in an old friend’s study after his death, raising a pair of unanswered questions: had the judge really once accepted a bribe influencing one of his court decisions, and if so, why?

If you like your detective puzzles rigorously tough, the tangled plot Nevins has in store for you is intended to challenge`your little grey cells to the limit. Now and then there is a regrettable emphasis on the overdramatic and the bizarre, but there’s a lot of punch packed into these pages, and it’s a reading experience that shouldn’t be missed.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 1, Jan-Feb 1979.

The Loren Mensing series —

Publish and Perish. Putnam, 1975.

Corrupt and Ensnare. Putnam, 1978.

The 120-Hour Clock. Walker, 1986. [also with Milo Turner]

Into the Same River Twice. Carroll & Graf, 1996.

Beneficiaries’ Requiem. Five Star, 2000.

Fri 19 Apr 2013

A Review by Francis M. Nevins, Jr.:

JON L. BREEN – Listen for the Click. Walker & Co., hardcover, 1983. No paperback edition.

There is a kind of detective novel set in a world of quiet gentility, a magical place without pain or grief or terror, a place where corpses don’t bleed and the emotions of the living are always under iron control. During the lulls in the plot a Nice Young Man and Nice Young Woman get together, and in the final chapter, preferably at a ritual gathering of the suspects, the Brilliant Detective effortlessly exposes the murderer.

The current generic name for a book of this sort is the English Cozy, because there’s a myth that it’s always been the exclusive property of British writers. In fact, however, a number of well-known Americans too have specialized in it, and Earl Derr Biggers’ half dozen Charlie Chan novels (1925-1932) are models of the form.

Jon L. Breen, an award-winning mystery reviewer, short-story writer, and Biggers devotee, has set his first detective novel on this turf . Amid an unobtrusive but knowingly sketched background of Southern California’s racing community, a jockey who had given many people potential murder motives is shot out of the saddle of a bronze horse statue on the lawn of a wealthy racing enthusiast’s widow.

The nephew of this dotty and whodunit-fixated old lady is racetrack announcer Jerry Brogan, whom Breen casts in the dual role of Nice Young Man and Clever Amateur Sleuth: if he wasn’t sleeping with his Chicana girlfriend without benefit of a marriage license, he might have stepped straight out of a Biggers novel of the 1920s.

Meanwhile, a suave con man and a shady private eye with literary ambitions launch a scheme to make Jerry’s aunt believe that they’re the Holmes and Watson of the west coast. In due course, after the underdog horse wins the big race, a Gathering of Suspects is arranged in the purest Charlie Chan movie tradition — “The murderer is in this room,” one of the small army of detective figures in the book intones solemnly — and all the clues are put in order.

Breen combines quiet charm, gentle digs at several types of crime fiction, and a puzzle complete with such original touches as an over-obvious Big Secret that mutates into a huge joke and a clue hidden in the book’s title. It’s no Secretariat, but lovers of the soft-spoken whodunit will have a fine canter around the track with this thoroughbred.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 7, No. 3, May-June 1983.

The Jerry Brogan series —

Listen for the Click (n.) Walker, 1983.

Triple Crown (n.) Walker, 1986.

Loose Lips (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Hot Air (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Jerry Brogan and the Kilkenny Cats (ss) Murder Most Irish, ed. Ed Gorman, Larry Segriff & Martin H. Greenberg, Barnes & Noble 1996.

Thu 9 Aug 2012

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

MARTIN H. GREENBERG & FRANCIS M. NEVINS, Jr., Editors – Mr. President, Private Eye. Ballantine, paperback original, December 1988. Ibooks, softcover, 2004.

I have long been fascinated by the “Presidential Connection,” the relationship between the mystery and the office of President of the United States. Following the triple traumas of Dallas, Vietnam, and Watergate, we had a publishing growth industry in which, literally, dozens of novels appeared featuring the President as either victim or villain.

Now the balance has shifted, and increasingly we find the man (so far) in the Oval Office appearing as detective. In recent years many of these stories have been about real Presidents. Three different authors have even written novels in which Theodore Roosevelt is featured, and he also solves a murder in Mr. President, Private Eye, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Francis M. Nevins, Jr.

The title is not exactly accurate, but you get the idea. Here are a dozen original stories, in each of which a real President gets to solve a crime. There is some evidence of hurried writing in this book, with anachronisms, always a danger in historical mysteries.

Also, in two of the weaker stories in the book, there is virtually no detection by Grant and Coolidge, respectively. However, there are also some stories which will give you a great deal of pleasure. Hoch has George Washington leave a dying message clue to a mystery which Abraham Lincoln solves half a century later.

Edward Wellen’s story about Millard Fillmore is surprisingly funny. Stuart M. Kaminsky’s mystery set in Missouri beautifully captures the simplicity and decisiveness of Harry Truman. Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Hoover detect at a Nevada silver mine in a story by Sharon McCrumb that I found to be the strongest in the book.

Finally, there is a clever K.T. Anders story about Gerald Ford which will make you clap your hand to your forehead and say, “Of course!”

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.

Mon 7 May 2012

DAVID GOODIS vs. THE FUGITIVE

by Francis M. Nevins

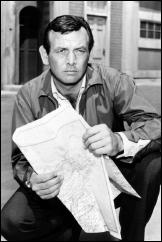

In the last few years of David Goodis’ life, one of the most popular TV series was ABC’s The Fugitive, the saga of Dr. Richard Kimble (David Janssen) who was wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder, escaped from the wreck of a prison-bound train, and spent the next several years on the run, criss-crossing the country, changing identities constantly, being stalked relentlessly by the Javert-like Lt. Gerard (Barry Morse) as he searched for the one-armed man who was the real murderer.

The series was produced by United Artists Television and ran on ABC for four seasons (1963-67) and 120 hour-long episodes. A year or so into its run, Goodis became convinced that the series was a rip-off of his own first crime-suspense novel, Dark Passage (1946), which had been serialized in the Saturday Evening Post before book publication and, a year later, became the basis of a Warner Brothers movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Both the novel and the movie told the story of Vincent Parry, who was not a doctor but did escape from prison after being wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder and, although never stalked by a cop, did set out to clear himself and find the real killer, who was not a one-armed man.

Goodis’ suit against United Artists TV raised three interesting legal issues. The one we’ll address first and last was whether The Fugitive infringed the copyright in Goodis’ novel. The Copyright Act of 1909, which was the governing law throughout Goodis’ lifetime, says that the owner of a copyrighted work has the exclusive right to “copy†the work. (The operative verb in the present Copyright Act is “reproduce.â€)

But neither statute sets any sort of standard for determining whether one work infringes another. What is that standard? Copyright law would be absurd and useless if it required absolute identity between the two: otherwise I could rip off The Da Vinci Code simply by changing the hero’s name to Langbert Robdon.

But the law would be equally absurd, and contrary to public policy and probably to the First Amendment also, if it allowed authors to claim copyright protection for the ideas in their works, so that, for example, the first person who wrote a novel or story about an intelligent dignified black detective could sue anybody else who later did the same thing.

In order to avoid both these extremes, the judicial decisions interpreting the Copyright Act have required for generations that in order to win an infringement suit a plaintiff has to establish that his work and the defendant’s work are “substantially similar†on the layer or level not of abstract ideas but of concrete expression.

The problem of course is that the line separating ideas from the expression of ideas is indefinable. But in order to prevail in an infringement suit the plaintiff has to establish substantial similarity on the expression side of that indefinable line. This is what Goodis set out to do when he sued over The Fugitive.

During the litigation the defendants took Goodis’ deposition, and their attorney questioned him intensely about what common elements he found between Dark Passage and The Fugitive. A few years ago, at a conference in Philadelphia, the law firm that had represented Goodis gave a presentation about the case. I was supposed to be there but missed my train.

Some kind soul knew of my interest and saved me a copy of Goodis’ deposition, which was handed out to those who attended. I decided that, shorn of side issues and redundancies, this document would make a good teaching tool in my Copyright Law course because it illustrates so vividly how the game is played.

Goodis, obviously well coached by his lawyers, tries to make the similarities seem as concrete as possible while the defense team tries just as hard to reduce them to abstract ideas. Let’s travel back in time and eavesdrop:

You say that you have seen some 20 to 25 … episodes of

The Fugitive, is that correct?

Yes, possibly more, but that would be a minimum, yes.

Based upon your familiarity with Dark Passage and that stated familiarity with The Fugitive, what similarities with respect to ideas do you see, if any, between the two works?

…[T]he nucleus of the plot is exactly the same… In Dark Passage, the entire story is based upon a situation involving a man who has been unjustly sentenced for the murder of his wife. Subsequently he…escapes from prison and seeks to find the murderer but through a series of unfortunate circumstances he is forced to keep running… [I]n the course of his escape … the protagonist, Vincent Parry, is aided by a young woman named Irene Janney who is present at the courtroom proceedings and who believes in his innocence. In a particular segment of The Fugitive … the protagonist, Richard Kimble, is aided by a young woman [played by] Suzanne Pleshette who is present at the courtroom proceedings wherein Kimble was found guilty and sentenced and who believes in his innocence….

Please continue with respect to any ideas that you found to be similar between Dark Passage and … The Fugitive.

Now in Dark Passage the protagonist, Vincent Parry, is portrayed as a mild-mannered man who is not bitter against society as a result of being unjustly condemned but who, when the situation demands it, is capable of great valor … and physical strength…. [T]he protagonist of The Fugitive, Richard Kimble, is portrayed in essentially the same light. Next point: In the course of his fleeing, Vincent Parry assumes disguise, physical disguise.

That is by having plastic surgery performed on his face, is it not?

That is correct, sir.

Continue, please.

In the course of his fleeing in this same connection, Richard Kimble in The Fugitive assumes disguise.

What type of disguise?

By having his hair dyed, by dyeing his hair. Next point: In Dark Passage the protagonist, Vincent Parry, confronts the actual murderer of his wife but is unable to use her confession to absolve himself inasmuch as the murderess falls out of a window to her death. In The Fugitive the protagonist, Richard Kimble, confronts the actual murderer … but is unable to use the murderer’s confession inasmuch as the murderer … gets away before the police arrive.

Was that particular [episode of The Fugitive] the same one to which you referred earlier as featuring Suzanne Pleshette?

No, sir…..

Please continue.

In the novel and film Dark Passage, Vincent Parry … is aided in the course of his escape by a somewhat offbeat taxi driver whose philosophy is somewhat cynical. In the same connection, in various segments of The Fugitive, the protagonist Richard Kimble is aided by various offbeat characters whose philosophies are somewhat cynical and at times world-weary.

Were any of them cab drivers?

Not to my recollection.

Go ahead.

In the novel and film Dark Passage, Vincent Parry in the course of his escape is harassed by a character [named Arbogast but] … who attempts to utilize Parry’s predicament for his own selfish motives … a form of blackmail…. In the same connection, in various [episodes] of The Fugitive Richard Kimble in the course of his fleeing is harassed by various individuals who attempt to utilize his predicament for their own selfish motives.

Did any of them attempt blackmail or extortion, do you recall?

To the best of my memory, these motives included various forms of monetary gain. I can’t tell you truthfully whether blackmail was utilized per se. I can’t remember.

In Dark Passage the fellow named Arbogast has followed Parry almost from the time of his escape up to the time of their final confrontation in the book…, where they meet in a hotel room and have their final confrontation which takes place there and subsequently in Arbogast’s car. Is that correct?

That is correct.

In The Fugitive series is there any one character who is continually following the protagonist, as you call him, Richard Kimble?

Yes. [There are] many, many instances where characters who attempt to use Kimble’s predicament for their own selfish gains… follow him.

[I]sn’t there one particular character in The Fugitive who is continually following Richard Kimble?

Not in that connection, not in the connection of utilizing Kimble’s predicament for his own selfish motives, no.

Is there any character, regardless of his motives, that is continually following Richard Kimble in The Fugitive series?

Yes… That is a detective….

Will you please continue with your comparison of ideas.

….I noticed in watching various [episodes] of The Fugitive similarity in characterization of the protagonist based mainly on the fact that the protagonist in Dark Passage is a man who…thinks of others before he thinks of himself and because of this is constantly falling into jeopardy….[I]n many, many segments of The Fugitive, the protagonist Richard Kimble is portrayed as a man who thinks of others before he thinks of himself and because of this is constantly falling into jeopardy.

Later in the deposition, obviously reading from notes, Goodis summarized the alleged similarities between his novel and the TV series.

(1) In Dark Passage Parry is primarily motivated by his determination to discover the truth concerning the murderer of his wife and the identity of the murderer. In The Fugitive Kimble is primarily motivated by his determination to discover the truth concerning the murderer of his wife and the identity of the murderer….

(2) In Dark Passage Parry is described as a man who is not especially aggressive or physically powerful but he is equal to the occasion when threatened with physical violence. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as a man who is not especially aggressive or physically powerful but he is equal to the occasion when threatened with violence….

(3) In Dark Passage Parry is portrayed as a quiet-spoken, reserved type, sensitive and kindly, considerate of others and with high standards of moral behavior. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as a quiet-spoken, reserved type, sensitive and kindly, considerate of others and with high standards of moral behavior….

(4) The treatment of Dark Passage places emphasis on Parry’s panic and fear of being apprehended before he can find the murderer of his wife rather than his bitterness at being unjustly accused and condemned. The treatment of The Fugitive places emphasis on Kimble’s panic and fear of being apprehended before he can find the murderer of his wife rather than his bitterness at being unjustly accused and condemned….

(5) In Dark Passage Parry is forced by circumstances to live and behave like a hunted animal. He can trust no one, not even those who want to help him. The treatment of the novel … places considerable emphasis on this aspect of the story. In The Fugitive Kimble is forced by circumstances to live and behave like a hunted animal. He can trust no one, not even those who want to help him. The treatment of the television series places considerable emphasis on this aspect of the story…

(6) In Dark Passage Parry is portrayed as a man whose “lips are not made for smiling,†a man whose eyes reflect a sadness caused by his loneliness and his awareness of the unpredictable tides of fate. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as an unsmiling, sad-faced man, whose eyes reflect a certain sorrow caused by his loneliness and his awareness of the odds imposed by the unpredictable hand of fate….

(7) In Dark Passage Parry’s actual escape from prison is merely a prologue for the ensuing events. The story itself is treated from the standpoint of the hazards facing an innocent man who must keep running and hiding while at the same time seeking the means to eventually prove his innocence. In the same connection, in The Fugitive the entire series is based on a montage used in various segments as a prologue for the ensuing events. This prologue, accompanied by the voice of a narrator, depicts the escape of an innocent man and is of course the springboard for the episode that follows. Regardless of the content of the segment, the plot and theme of the entire series are based on the hazards facing an innocent man who must keep running and hiding while at the same time seeking the means to eventually prove his innocence…

[W]hat is the theme of

Dark Passage?

…The theme of Dark Passage involves the plight of an innocent man condemned for the murder of his wife, constantly on the run after having escaped from the authorities, aided by those who sympathize with him and menaced by others who are motivated by their own selfish interests.

What do you understand…to be the theme of [The Fugitive]?

Essentially the same….

What is the plot of Dark Passage as you understand it?

…[A]n innocent man condemned to life imprisonment for the murder of his wife escapes from prison and is aided by those sympathizing with him and menaced by others who are motivated by their own selfish interests.

What did you consider to be the plot of The Fugitive … to the extent that you found one?….

The same thing, essentially the same.

The defendants made a motion for summary judgment, asking the court to throw out the suit purely on legal grounds, but it wasn’t based on any claim that as a matter of law Dark Passage and The Fugitive were not substantially similar.

In effect UA TV took the position: “Assuming for the sake of the argument that we did take substantial material from Dark Passage, we were legally entitled to do so.â€

The first of the two legal arguments they offered was based on the 1945 contract by which Goodis for $25,000 sold Warner Bros. the movie rights in his novel. Like most such contracts in Hollywood’s golden age, this one included language permitting the studio not only to make a movie based on the novel but to remake it as often as the studio chose. United Artists TV claimed that The Fugitive was legal on the basis of those remake rights, which it had bought from Warners.

Could the contractual language have been broad enough to justify such a claim? Could a clause primarily intended to authorize one or at most a handful of theatrical remakes be stretched to justify the making of a TV series that lasted for 120 hour-long episodes?

The federal district court hearing the case ruled that it not only could be but was, and on January 2, 1968, almost a year after Goodis’ death, granted summary judgment to the defendants on that basis, quoting from the 1945 contract at great length. Anyone who wants to go to a law library and read the decision will find it in Volume 278 of the Federal Supplement, beginning at page 120.

The defendants’ second legal argument grew out of the Goodis deposition. Apparently the UA TV attorneys hadn’t previously realized that the Saturday Evening Post had paid Goodis $12,000 for the right to publish Dark Passage in six weekly installments before its publication in book form.

Unfortunately the only copyright notice in those six issues of the Post was the general notice on the table of contents page in the name of the Curtis Publishing Company. But Curtis wasn’t the copyright owner of Dark Passage; it was merely the licensee of magazine serialization rights from Goodis, the real copyright owner.

Therefore, the defendants argued, Dark Passage had been published serially without a proper copyright notice, with the consequence that it had been in the public domain ever since and anyone could make any use of it that they pleased.

This may sound to 21st-century ears like an argument worthy of Alice in Wonderland or Catch-22, but under the 1909 Copyright Act, which was in force at the time of this case and remained the law until the beginning of 1978, it was a sound contention, and the District Court granted UA TV’s motion for summary judgment for that reason also. The Goodis estate appealed both rulings.

The case moved through the legal system like a frozen snail. It took more than two years for the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to hand down its decision, but from the viewpoint of Goodis’ successors it was worth waiting for.

In Goodis v. United Artists Television, which was dated March 9, 1970 and can be found in Volume 425 of the Federal Reporter, Second Series, beginning at page 397, the appeals court reversed the trial judge on both grounds.

All three appellate judges sitting on the panel — Kaufman, Lumbard and Waterman — agreed, in Chief Judge Lumbard’s words, that “where a magazine has purchased the right of first publication under circumstances which show that the author has no intention to donate his work to the public, copyright notice in the magazine’s name is sufficient to obtain a valid copyright on behalf of the beneficial owner, the author or proprietor.â€

The court’s refusal to impose Draconian consequences on an author because of a minor defect in a copyright notice constituted a landmark decision at the time, and the law has continued to evolve in the same direction ever since. Indeed under our present Copyright Act no notice at all is necessary in order for a work to be protected.

On the question of interpreting the contract between Goodis and Warners the three appellate judges split. Lumbard would have upheld the district court’s grant of summary judgment but was outvoted by Kaufman and Waterman.

“The question presented here,†Waterman wrote, “is whether the contract language demonstrates unambiguously that Goodis meant to convey to Warner Brothers the right to create a television series such as The Fugitive or whether a genuine issue of material fact exists as to what the parties intended by the language they used… It is our holding that the contract language does not so clearly permit production of The Fugitive as to entitle the defendant to a grant of summary judgment.â€

This too constituted a major improvement in authors’ rights. Thanks to the court’s refusal to hold as a matter of law that the contract between Goodis and Warner Bros. conveyed extremely broad rights as UA contended, it would be up to a jury to decide that issue if and when the case came to trial.

That trial never took place. After the Second Circuit decision the defendants paid Goodis’ successors a small amount of money to drop the suit and go away. But since UA TV had never admitted any substantial taking from Dark Passage, at trial Goodis would still have needed to show substantial similarity between his novel and The Fugitive.

Could he have done so? I’ve read the novel and seen the movie based on it, and 40-plus years ago I watched The Fugitive TV series regularly. I’ve also taught copyright law for almost 40 years and written some crime-suspense fiction of my own, and of course I’ve read Goodis’ deposition several times.

My tendency is to demand a strong showing before I find two works substantially similar, so perhaps I’m a bit prejudiced. But Goodis’ case strikes me as very weak, so weak that the trial court might well have refused to allow a jury even to consider the issue, on the ground that no reasonable jury could have decided in Goodis’ favor on the evidence he presented.

We’ll never know. A lawsuit is like a horse race: anything can happen. One of the great lawyerly virtues is prudence. It was prudent of UA TV to offer a settlement and prudent of the Goodis successors to accept it.

We also cannot know whether Goodis himself would have accepted a settlement had he lived. But if there’s an afterlife and they serve liquor, he no doubt would have toasted the wisdom of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in using his case to strike two blows on behalf of all authors living and dead.

Tue 23 Feb 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

This column isn’t my usual hodgepodge but sticks to one subject and therefore deserves a title. How about “Call for Campion Complete”?

A few months ago and for no particular reason I decided to read the first series of Margery Allingham’s short stories about Albert Campion in the order of their original publication as far as that could be determined.

After some research on my own shelves and in The FictionMags Index, which is by far the leading Web source when it comes to identifying where almost any work of short fiction in English first appeared, I identified 18 tales that clearly belonged on my reading list: two dating from 1936 or earlier, fifteen that appeared in The Strand Magazine between late 1936 and 1940, and a singleton first published in a London newspaper shortly before the outbreak of World War II.

There are also two short-shorts that present bibliographic as well as criminous puzzles but let’s save them for a while, shall we?

Revisiting the Easy Eighteen between 70 and 80 years later, I found them by and large to be as clever, charming and delightful as I remembered them from decades ago. Most of the crimes in these stories are jewel thefts or con games, with hardly a murder anywhere but plenty of indications in the later tales that England is moving ever closer to that form of mass murder we call war.

“The Man with the Sack” (The Strand, December 1936) is a light-hearted Christmas story in which Campion frustrates a jewel scam while attending a holiday party at one of those stately homes of England that abound in Golden Age crime fiction.

Two years later, during the last peacetime Christmas season, came “The Case Is Altered” (The Strand, December 1938), where the setting is yet another holiday party at yet another stately home, but this time the McGuffin is a secret document revealing the country’s plans to purchase huge numbers of war planes.

The next Campion tale in The Strand and for my money one of the weakest is “The Meaning of the Act,” an international espionage trifle which came out in the issue of September 1939, the month Hitler invaded Poland.

The eighteenth and last story in the batch is “A Matter of Form” (The Strand, May 1940). This one centers around a magnificent con game which could only have been devised during the so-called phony war, a time of “children in uniform and bankers in mourning” but with minimal disruption of ordinary life, so that Campion can still enjoy an oyster appetizer in the heart of a London soon to be blitzed.

The two stories that predate the fifteen in The Strand and a third from near the end of the cycle need to be treated separately.

“The Border-Line Case” is shorter than any Strand tale and, unlike any other Campion exploit, has a first-person narrator, namely Allingham herself. A careless reading of the story might suggest that she was cohabiting with her character, but then one notices a few subtle hints that besides the narrator and Campion and Detective Inspector Stanislaus Oates, there is a fourth and silent person in the room, presumably P. Youngman Carter, to whom Allingham had been married since 1927.

My guess is that this neat little impossible-crime story dates from between 1933 and 1935, making it Campion’s first short exploit.

“The Pro and the Con” is the same length as the Campion stories in The Strand but doesn’t seem to have appeared there. In this tale we find Campion bound, gagged and beaten up by an Edgar Wallace-style gangster, and that fact alone suggests a date slightly earlier than the Strand fifteen.

“The Dog Day” first appeared in the London Daily Mail sometime in June 1939, probably having been rejected by The Strand because of its complete crimelessness.

So much for the eighteen Campion tales that definitely belong on my reading list. Now we come to those two pesky short-shorts, each limited to a single scene and just one or two characters if you don’t count Campion and Scotland Yard’s Stanislaus Oates and the corpse.

The earlier of the pair to appear in the U.S. was “The Unseen Door” (Mystery Book Magazine, August 1946), which takes place in the billiards room of a London club. No concrete detail hints that the story might have been published in England ten or more years earlier and therefore belongs in the first series.

My hunch that it does stems from the other short-short, “Mr. Campion’s Lucky Day” (Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, April 1947). Judging from his introduction, founding editor Fred Dannay thought Allingham had just written the tale. In the EQMM version Oates is given the rank of Superintendent, which he first sported in “The Old Man in the Window” (The Strand, October 1936). But when this tale finally appeared in a collection (The Allingham Minibus, 1973), Oates’ title is Detective Chief Inspector!

This strikes me as highly persuasive evidence that the story first appeared in England before October 1936. And is it plausible that two Campion short-shorts with as much in common as this one and “The Unseen Door” could have been written more than ten years apart? My tentative conclusion is that both are early entries in the Campion saga. Perhaps someday we’ll know for sure.

While immersed in my Allingham project I came upon a curious connection between one of these tales and perhaps the most powerful of all English noir novels, Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock (1938).

The sociopaths from the lower depths whose leader is the sexually terrified young racetrack racketeer Pinkie refer to women in several terms like “buers” which I’ve never seen elsewhere. But the Greene character who calls a young woman a “polony” has his counterpart in Allingham’s “The Meaning of the Act,” where a lower-class pickpocket uses the same word, although she (or perhaps her Strand editor) spells it “palone.”

To anyone eager for more about this obscure contribution to English slang: Google the word in either spelling and you will be enlightened.

Even reading the fifteen Campion stories from The Strand requires more work than one might think. Besides needing to be at home in FictionMags Index, and assuming you don’t own copies of the magazine from the second half of the 1930s, you must have access to most of the Allingham collections published over the past 70-odd years.

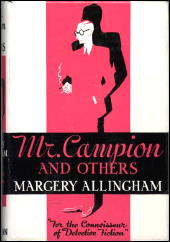

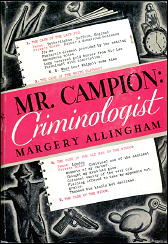

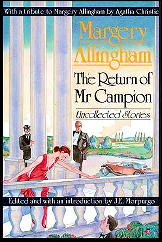

The second edition of Mr. Campion and Others (Penguin, 1950) contains twelve of the fifteen, although chaotically out of order. But the 1936 Christmas story “The Man with the Sack” was collected only in Mr. Campion: Criminologist (1937) and The Allingham Minibus (1973), and its analogue from two Christmases later, “The Case Is Altered,” remained uncollected until The Return of Mr. Campion (1989).

That volume is also the sole hardcover source for the crimeless but charming “The Dog Day.” “The Border-Line Case” and “The Pro and the Con” were collected in both Mr. Campion: Criminologist (1937) and The Allingham Case-Book (1969), with “Border-Line” also appearing in the first edition of Mr. Campion and Others (1939) but not the second (1950).

Those pesky short-shorts “The Unseen Door” and “Mr. Campion’s Lucky Day” remained uncollected until the Minibus started to roll.

Then there’s one final problem. If you set out to read the Campion stories in order of first publication, as I did, you wind up having to save one of the earliest for last.

How can this be? Because of “The Black Tent,” which Allingham clearly wrote around 1936 but then put aside and rewrote as “The Definite Article” (The Strand, October 1937). The first version remained unpublished until almost a quarter century after her death, when it was included in a British anthology (Ladykillers: Crime Stories by Women, 1987) and then in the most recent Allingham collection to date, The Return of Mr. Campion (1989).

What a mess! Wouldn’t it be loverly if someday all the Campion shorts were brought together in their proper order in a single book?

NOTE: Previously on this blog: A Review by Mike Tooney: MARGERY ALLINGHAM – Mr Campion and Others.

[UPDATE] 02-25-10. I [Steve] posted this last question asked by Mike on the Yahoo Golden Age of Detection group. That it was a good idea, everyone agreed at once. Others wondered if other authors might also be honored with Complete Short Story collections, including (and especially) Edward D. Hoch. Here’s a reply from Doug Greene, head man at Crippen & Landru, which he’s graciously allowed me to reproduce here:

I fear that a complete collection of the Campion shot stories would make a hefty volume, but I’d love to see it done. C&L, however, specializes in books of uncollected short stories — though we made an exception of C. Daly King’s The Complete Curious Mr. Tarrant, which added 4 or 5 previously uncollected stories to the original 1935 volume.

The agent for Lillian de la Torre would like us to collect all of her Dr. Sam: Johnson stories into a single book — including 5 or so uncollected tales, but again the volume would be very long, and pricey to publish.

On the Hoch suggestion, Ed wrote almost 1000 short stories, which would fill about 66 volumes of the usual C&L size. We’ve already published 6 Hoch collections and have plans for at least 3 more… depending on energy and cash flow.

Our latest, Michael Innes’ Appleby Talks About Crime, is now in print, and we’re sending out copies to our subscribers as quickly as possible — especially since I leave for England in about a week (and will stay 10 days). After I return, we’ll take orders from the general public. And to answer an unspoken query, all the stories are previously uncollected.

Doug G

Then this response, also first appearing as a post on the Yahoo GAD group:

Barry Pike, chairman of the Margery Allingham Society, has been trying for a while to persuade Vintage, the UK publishers, to do this, but he doesn’t seem to be getting very far.

Lesley

—

Lesley Simpson

http://www.margeryallingham.org.uk

In spite of some less than entirely optimistic answers, thank you both, gentlemen!

Steve

Sat 15 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

FRANCIS M. NEVINS, JR. – The 120-Hour Clock.

Walker, hardcover, 1986. Paperback reprints: Penguin, 1987; iUniverse, 2000.

One of the last mysteries published in 1986, The 120-Hour Clock by Francis M. Nevins, Jr., turned out to be one of the most enjoyable. Nevins has abandoned (except for a cameo appearance) his previous series sleuth, Loren Mensing, in favor of an extraordinary con man, Milo Turner, whose life and happiness depend upon his solving a murder.

The first chapter is an absolute grabber, beginning with a paragraph from Turner’s notebook in which he sounds the way Cornell Woolrich might have if he were reflecting on his career as a con man, instead of as a writer. After that we ride the Milonic roller coaster, mostly through New York and St. Louis, a world which includes Schultz’s Human Supermarket and Lafferty’s Identity Bazaar. .

Nevins operates on two levels. First, his book is a big-caper novel and practically a treatise on the scam, though its pace is far from scholarly. Using verbs the way Nevins does (purists may blanch), I can say I page-turned compulsively. Yet Nevins evokes considerable poignancy from his character, and, incidentally, he writes excellent love scenes, several with a nicely erotic touch.

If you’ve heard that Walker only publishes “cozy” books, disenchant yourself of that notion. The sex and the language are strong here, but they are appropriate; nothing is gratuitous.

The mystery reader of the future, say in the twenty-second century, can learn a great deal about how we lived in the latter half of this century from The 120-Hour Clock. There are scenes in large motels that perfectly capture how it is to spend time there.

In another scene, Turner and a woman he loves walk through Manhattan: “I linked my arm in hers as we trod the empty streets, talking in whispers so we wouldn’t wake the bag people sleeping on the steam vents.”

I’m not sure I believe all of this book, especially the ease with which Turner establishes new identities. I’m not ever sure I was supposed to. After all, Nevins is really in the same field as Turner, who says he’s “in the business of giving apparent reality to what doesn’t exist.” Both are highly successful at their professions.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.