Search Results for 'Henry Kane'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Tue 11 Jul 2023

HENRY KANE “The Case of the Murdered Madame.†PI Peter Chambers, Lead story in the collection of the same name: Avon #646, paperback original, 1955. Reprint edition: Signet D2646, paperback, May 1965.

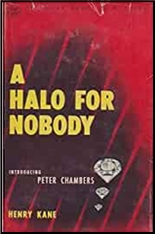

Both Henry Kane, the author, and Peter Chambers, his most well-known private eye detective character, came onto the scene at the same time, in 1947, first with a handful of stories for Esquire magazine, then a hardcover novel, A Halo for Nobody, from Simon & Schuster. I haven’t followed Kane’s career well enough to state this as more than a working hypothesis, but based only on the scanty evidence I have so far, Peter Chambers’ early adventures seem to combine as well as anyone hard-boiled PI mystery fiction with the older-fashioned traditional detective novel, complete with clues, alibis, and the like.

Take “The Case of the Murdered Madame,†for example. While not a locked room mystery or an impossible crime in any sense, it is a case in which a murder takes place in a house where there are only a limited number of suspects, each with a common motive – that is to say, the theft of $100,000 in cash the dead woman has made abundantly known to the other tenants of the rooming house catering to theatrical folk living there.

Peter Chambers’ job: find out who did it.

The fact that it was a dark rainy night comes into play in twofold fashion, first in terms of limiting the number of suspects, then secondly in providing Chambers with the clue he needs to name the killer.

The story is too short to provide much in the way of characterization, but the sheer rhythm of Kane’s prose, almost unique in the annals of detective fiction, is a pure plus that adds considerably to the enjoyment of this short but snappy tale.

PostScript: The Avon paperback of the same title appears to have been the first appearance of this story. What caught me by surprise in reading the Signet reprint was that there is no contents page, and therefore no suggestion ahead of time that the book is a collection of three stories, the other two, also cases cracked by Peter Chambers, those two both first appearing in the pages of Manhunt magazine.

In any case, though, while reading the story, I was thinking it was a novel, and here Peter Chambers was, summing the case up against the killer, and I’m only a third of he way into the book. What’s going on, I thought. What kind of twist is this?

Tue 2 Aug 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY TONY BAER:

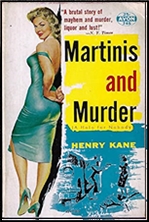

HENRY KANE – A Halo for Nobody. Peter Chamber #1. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1947. Dell #231, mapback edition, 1948-49? Also published as Martinis and Murder, Avon #745, paperback, 1956; Avon T-460, paperback, revised edition, date?

So I’ve been working my way thru James Sandoe’s hardboiled checklist, which I’ve found to be pretty reliable. And this one appears on it with the following faint praise from Sandoe: “Peter Chambers’s first case and the only one in which I could discover any pleasure.â€

NYC private detective Peter Chambers gets hired to find out who murdered the slutty wife of a jewelry store owner.

Chambers is a pretty likable character, hard drinking and the ladies love him. And he them.

And as Chambers further digs, it looks like the jewelry store might be an abject lesson in vertical efficiency: Steal the jewels, redesign the settings, and sell them as new.

Fairly standard detective novel, maybe a par, but spruced up with some of the best hardboiled metaphors and turns of phrase this side of Chandler which may flip that par to a birdie:

“He had a face like a folded hat.â€

A “blonde with verve and eyes and small curves and a pink revealing gown and voltage.â€

“[W]ith forbidden love and fresh ardor as freely distributed amongst them as cockroach paste in an infested pantry.â€

“’[T]he dainty Dorothy can furnish an alibi. She was in bed.’ ‘The dainty Dorothy was in bed,’ Archie mimicked. ‘That’s a fine alibi. It’s a fine alibi for a bedbug. How would you know? Were you there?’ ‘Uh-huh.’â€

“She looked at me and blood went to my head and got crowded like Belmont raceway on a sunny Saturday afternoon.â€

“[She] came up with a laughable little .22, a small black instrument with a tiny muzzle, and I didn’t laugh because the trigger was being squeezed with determination and five cute little pellets entered into me, in the region of the stomach, like five baby fingers into porridge.â€

“I pulled at the triggers of both pistols and pumped and I saw blood burst from his head and I watched part of his face dissolve into squirming crimson and I saw him go slowly down behind the desk, like a marionette Santa Claus down a chimney, and I kept pulling at triggers long after there was no sound in the room except the futile foolish click-click of hammers on empty shells….â€

Fri 22 Apr 2022

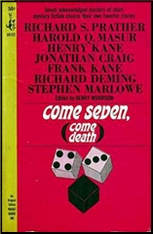

HENRY KANE “The Memory Guy.†PI Peter Chambers. First published in Come Seven, Come Death, edited by Henry Morrison (Pocket, paperback original, 1965). Reprinted in Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine (US), March 1966.

In “The Memory Guy†Peter Chambers is hired to do one thing – find who’s been leaving an aspiring Broadway actress phone calls threatening her father’s life – and ends up doing another. To wit: saving her from being accused of killing him. It seems that he was doing his best to keep her from her desired choice of career, including the rather drastic measure of persuading her to marry his law clerk, a man with a photographic memory.

Hence the title.

If you were to read the blurb for this particular story on the back cover, it gives the entire plot away, so don’t. As a pure detective story, it’s too short to linger in your memory for very long afterward, but it’s very well constructed.

What I found disappointing, is that there’s nothing of Peter Chambers himself in the story. The Personality he’s developed in earlier stories doesn’t exist in this one. The PI the girl hires could have been anyone. In fact, he needn’t even be a detective, just someone she knows who’s a little more observant than a stranger off the street.

Thu 24 Feb 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

HENRY KANE. “Suicide Is Scandalous.†Novelette. Peter Chambers. First appeared in Esquire, June 1948. Collected in Report for a Corpse (Simon & Schuster, 1948). Reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carrol & Graf, 1988).

It’s only my opinion – I have no stats to back this up – but as an author of any number of crime novels, and in particular, the creator of New York City-based PI Peter Chamber, Henry Kane has largely been forgotten in recent years. One exception is, of course, Mike Nevins’ covered his early years in one of the monthly columns he does for this blog. One of the stories covered, in fact, is this very one. Go here.

This is one of the longest excerpts I’ve ever inflicted upon readers of this blog. Bear with me. A little old lady is sitting in Peter Chambers’ office on the other side of his desk. Bear with me. Here goes:

She put the handkerchief away. “The Lieutenant sent us.”

“What Lieutenant?”

“The man downtown. The Detective-lieutenant.”

“Parker?”

“Yes, sir. Lieutenant Parker.”

“A real policeman.”

“A fine, good man.”

“The best.”

“He said this was where to throw it.”

“I beg your pardon.”

“That’s what he said.”

“Throw what?”

“My money. That is, if I insisted on throwing it away.”

“I beg your pardon.”

The smile came back, very tired among the faint wrinkles on her face, and it did something to you, no matter you’re a cynical wiseguy private richard battened down behind a desk over which too much evil has spewed. It got to you, in a corner inside of you, like “Stardust” on strings in a sawdust saloon after a good many brandies. I grunted.

“How much?”

Her eyebrows peaked. “How much?”

“How much do you insist on throwing away?”

“Oh. He said you were expensive. He also said you were a crook.”

“Look, lady– ”

“He was joking, of course. A thousand dollars, perhaps fifteen hundred … ”

“Oh.” Good-bye Stardust, because business is business, and you have got to have the pretzels for your beer. On the other side of the. desk sits your sucker — always; they wouldn’t be on the other side of that desk if they didn’t need you badly. Either you squeeze them, or they squeeze you: you learn that early, Always, on one side of the desk sits a sucker. Could be me.

“Two thousand,” I said.

Now either you find that an extraordinarily fine piece of writing, or you don’t. Kane’s prose, at least in this story, I’d place on the spectrum somewhere between Raymond Chandler and the Dan Turner stories by Robert Leslie Bellem, but closer to Chandler than the out-and-out wackiness of a Dan Turner story:

“Don’t know nothing from absolutely nothing.” He put a wide hand on my chest and he shoved with relish and sharp determination, and the door slapped shut in my face. Mr. Gino Stark got filed away as a handsome young man with a tough-guy complex that needed treatment. Something psychiatric. Like a haymaker.

I took a cab, still rankling along the chest and rumbling around the stomach and trying to engage reasons for administering the treatment for our Gino’s complex, all of which is good for the passage of time, because before I knew it I was paying off the hackie in front of Two Ninety Park.

I pushed my hat back and I looked up at the narrow four sandstone stories of a very svelte little pigmy amongst the flat-faced monsters that go to make up our canyon of Park. No doorman. No nothing. Just a silver-grilled ninon-backed glass door with an ivory boundary and a horse’s head for a phony knocker and a shining lock. I stuck the key in that Williams had given me and I was in a hallway with enough plush for a lupanar, and a curlicue stairway. Very dandy, but a walk-up, nevertheless. Ah, me, and the rasp of a sigh: your detective trudged, grudgingly, bending over to study nameplates. On the second floor front it said BENTLEY.

So, OK. What’s the story about? Chambers’ client, the little old lady from the first except above, does not believe her daughter committed suicide. The police are convinced; that’s why she’s hired Chambers. But besides suicide being scandalous, there is a small matter of a will. The dead girl was rich. Her will leaves half to her mother, half to her sister. If it was murder, and the sister did it, who gets all the money?

Besides being an above average PI story in and of itself, “Suicide Is Scandalous†ends with a lot of detective work going on. There was, in fact, so much detective work going on that I found it confusing. Oh well. You can’t have everything.

Thu 2 Dec 2021

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

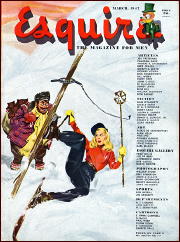

In 1946, soon after the end of World War II, the editors of the high-paying Esquire decided to launch a series of short detective stories and invited several authors to create a new character for possible publication in the magazine. Among those solicited was that incomparable filbert Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), who strung together an outrageous plot about a barking clock and an astigmatic witness and dreamed up a 7½-foot-tall mathematically-educated hick from the sticks as his new detective.

Reasonably enough, Esquire rejected the story. Who won the prize that Keeler lost? A guy who happened to have the same first and last initials as our Harry. The subject of this column.

***

About the life of Henry Kane very little has surfaced. He was born in New York City on 18 May 1908 as Henry Cohen and apparently graduated from one of the city’s several law schools in the 1930s. How long he practiced law is unknown, but it does seem clear that he preferred writing to legal work.

Whether he served in World War II is also unknown. At the time of Esquire’s hunt for a new series character he seems to have published nothing, and what the editors saw in him is likewise a mystery. The character he created for the magazine was Peter Chambers, a tough but sophisticated Manhattan private richard (as he prefers to call himself) whose first appearance in short-story form was “A Glass of Milk†(Esquire, February 1947).

It was also early in 1947 that Chambers debuted as protagonist of a hardcover novel. Whether the early short stories preceded or followed A HALO FOR NOBODY (Simon & Schuster, 1947) is anyone’s guess: my own is that at least the first couple of them came first. Kane stayed with S&S for a few years, then migrated to the field of paperback originals where he flourished during the Fifties and Sixties, having Chambers narrate his own cases in a wackadoodle style which his admirers have dubbed High Kanese.

It’s likely that Chambers was the uncredited inspiration for the hit TV series PETER GUNN (NBC, 1958-61), for which the tie-in novel (PETER GUNN, Dell pb #B155, 1960) was written by, you guessed it, Henry Kane. Later in the swinging Sixties Kane reconfigured his character as protagonist in a series of X-rated paperbacks for Lancer (1969-72).

During the final phase of his career he turned out a number of stand-alone hardcover thrillers, some under his own byline, others as by Anthony McCall, Kenneth R. McKay, Mario J. Sagola (a name probably meant to evoke the Godfather saga) and Katherine Stapleton. He died in his home at Lido Beach, Long Island on 10 October 1988.

***

A HALO FOR NOBODY opens with a report by Chambers to his friendly enemy NYPD Lieutenant Louis Parker, and of course to us: he was walking down Park Avenue in the lower Eighties on the way to an appointment with a potential client when, a block or so ahead of him, he witnessed an attempted kidnapping and the murder of a woman, who turns out to be the potential client’s wife.

Being armed at the time — which establishes, I suppose, his machismo — he fired several shots into the back of the taxi in which the criminals were escaping. The taxi is later found in Central Park with two dead men in it: the driver and a known hoodlum.

Soon afterwards, Chambers is hired by the dead woman’s husband not to solve the murder of his wife, whom he hated, but to find out why someone is trying to blackmail him when he knows he’s done nothing blackmail-worthy. It would take several pages of summary to penetrate deeper into Kane’s Chandleresque plot labyrinth and I doubt it would benefit anyone to read them.

When A HALO FOR NOBODY was published in 1947, Kane was touted by Simon & Schuster as “a worthy successor to Dashiell Hammett.†Talk about ridiculous! The main connection between the two is that Kane, like so many others, borrowed from Hammett the climax of THE MALTESE FALCON.

To Raymond Chandler he owed a bit more, including some elements of his protagonist — even the names have the same cadence, Philip Marlowe and Peter Chambers — and the all-but-incomprehensible labyrinthine plot, although he does keep to a reasonable minimum the vivid figures of speech in which Chandler indulged perhaps too often.

The stylistic feature of HALO that jumps out at the reader is Kane’s habit of converting several short sentences into a single long one by the repeated use of the most common conjunction in the language. Here’s an example from a nightclub scene.

Blue smoke curled and wavered and curtained the ceiling and the girl rocked at the microphone and her eyes were closed and her dark eyelids glistened and she sang slowly in a deep, hushed voice, throbbingly, against the wash of subdued conversation.

I have a vague recollection that this trope started with Hemingway but I doubt that Papa used it to anywhere near the same extent as Kane.

Anyone writing a dissertation on political incorrectness in PI fiction will go no farther than Chapter Four when Chambers encounters a gay ex-gangster and calls him, to his face, “a fairy, a phony, a queerie, a pervert.†Any such reader will miss perhaps the most memorable scene in HALO, the gunpoint tête-à -tête between Chambers and the most cold-blooded of the novel’s three murderers, who is also perhaps the most philosophical killer in the entire Kane Kanon:

“Chambers, a long time ago I learned it was dog eat dog. A human life means nothing; your own life, conversely, means everything. We are taught differently. Comes a war — how quickly they attempt to reteach us. You have no personal grievance against the soldier of the enemy — -but you kill him, unfeelingly. A human life, in the vast perspective, means nothing; but protect yourself. With yourself, there is no perspective.â€

At the end of the scene a slightly wounded Chambers faints, vomits several times, finds a bottle and guzzles nonstop for five minutes. He then segues into the MALTESE FALCON climax from which, unlike Sam Spade, he emerges with five bullets in his stomach. From his hospital bed he identifies the third and final of the book’s murderers. That too, I suppose, is machismo.

In his review for the San Francisco Chronicle (16 February 1947) Anthony Boucher wisely made no attempt to summarize the plot of HALO but limited himself to describing Chambers as “a private eye who thrives on drink, wenching and coincidences†and the book itself as a “[r]easonably good toughie, at once more literate and more confusing than most….†I cannot better that description.

***

The second Chambers novel, ARMCHAIR IN HELL (1948), is similar to HALO in opening with three corpses. It’s after midnight when our private richard is ungently pulled out of an alcoholic haze by one of his most lucrative clients, a wealthy gambler known as Ziggy who’s found a naked woman with her throat slit in his house on West 76th Street.

At the house Chambers and Ziggy find two additional corpses: a henchman of the gambler’s and a prominent art dealer. Chambers has his client steal a car, take the bodies and dump them near the river, then joins Ziggy for a 4:00 A.M. conference over cheesecake and coffee and learns that the gambler had been promised $500,000 to act as go-between in the transfer of some priceless tapestries that had been taken out of France by the Nazis during World War II.

Those tapestries are Kane’s version of what Hammett called the black bird and Hitchcock the McGuffin. Like any McGuffin worthy of the name, this one is being sought by an assortment of questionable characters, including a blonde sexpot, a brunette sexpot, an art critic (whom Chambers describes as “a California elfâ€), an oddball Frenchman, a pool shark, a ballroom manager, and a sinister dwarf with a huge moronic goon who, in a scene reminiscent of the beating of Ned Beaumont in Hammett’s THE GLASS KEY, marks Chambers up with a set of brass knuckles.

The climax calls to mind the conference among all the parties near the end of THE MALTESE FALCON, with Chambers pulling the strings so that the murderer is gunned down in front of witnesses by one of the other contenders for the tapestries.

Our friend the student of political incorrectness will find short rations in this one, mainly the scene where Chambers asks about another character’s sexual preference or, as he phrases it, whether the man is “a nancy…. A fruit, a milky way, a buttercup.†Any such student who stopped there would miss perhaps the most interesting moment in the book, a sort of meta-scene where Chambers describes not only himself but almost every PI who came into the genre in Chandler’s shadow.

He “has no wife, or sleep, or food, or rest. He drinks, drinks more, and more; flirts with women, blondes mostly, who talk hard but act soft, then he drinks more, then, somewhere in the middle, he gets dreadfully beaten about, then he drinks more, then he says a few dirty words, then he stumbles around, punch-drunk-like, but he is very smart and adds up a lot of two’s and two’s, and then the case gets solved….â€

***

Later that year Simon & Schuster published REPORT FOR A CORPSE (1948), a collection of Kane’s first six short stories, all from Esquire. Whereas in his book-length cases Chambers had been a member of a PI firm complete with senior partner, an old-maidish secretary and at least three legpersons, in these shorter tales he’s a lone wolf with only the secretary Miranda Foxworth carried over from the novels.

For some unaccountable reason the stories in book form are not printed in chronological sequence but I shall cover them in Esquire’s order.

“A Glass of Milk†(February 1947) opens on a Sunday afternoon as Chambers enters an elegant Madison Avenue drinking place, spies a beautiful blonde at the end of the bar nursing a glass of milk and orders another: obviously a prearranged signal. The blonde leaves and Chambers follows her to her apartment where she makes him a real drink, tells him she’s changed her mind about hiring him, and gives him fifty dollars for his time and trouble.

That evening he’s visited by his friendly enemy Lieutenant Parker, telling him that the woman has been found dead, with her face mashed in, and Chambers’ prints all over the hotel suite. Chambers explains about the assignation at the bar but the apartment staff insist she never went anywhere that day and the bartender says he never served any blonde a glass of milk.

Instantly we’re reminded of the situation in Cornell Woolrich’s iconic novel PHANTOM LADY (1942), with Chambers taking the part of the man who’s wrongly accused of his wife’s murder while he was in a bar with a woman no one else saw. Kane’s version of the story makes more sense than Woolrich’s but then he didn’t have to reach book length.

Criminal lawyer Sonny Evans, who was an offstage character in A HALO FOR NOBODY, has a scene in “A Matter of Motive†(March 1947). It’s at his recommendation that Chambers is hired when a drugstore owner is charged with the murder of one of his clerks, who was blackmailing him over his sideline as a narcotics dealer, and with whom he had an appointment around the time of the killing.

The next most likely suspect is the dead man’s nightclub-singer fiancée, who was also the beneficiary of his life insurance policy. Chambers searches the scene of the murder and finds a letter indicating that the dead man was having an affair with his blackmail victim’s wife and was about to break it off. With two female suspects, both of whom admit they were near the crime scene at the crucial time, plus of course his client, who also had motive and opportunity, Chambers figures out who done it in a manner reasonably fair to the reader.

You’d never guess from the flippant title of “Kudos for the Kid†(May 1947) that it’s quite close to a traditional detective tale, with Chambers addressing his friendly enemy as “my dear Parker†and the lieutenant in turn griping about the PI’s Sherlock Holmes act.

Chambers happens to stop at a Fifth Avenue candy store to ogle a beautiful blonde staring into the shop window and is immediately invited to accompany her to an apartment hotel. What sounds like an invitation to bedplay quickly turns out otherwise: the blonde had lost a valuable emerald earring at a dance and was waiting for the person who had advertised in the newspaper, asking whoever lost the earring to meet him in front of the candy store, prove ownership of the jewel and take it back.

Matters are straightened out in the hotel’s tower suite but before leaving Chambers discovers the blonde’s wealthy father dead of two bullet wounds in the stomach. Parker and the police doctor call it suicide but Chambers insists that suicides don’t shoot themselves in the stomach and instantly deduces the murderer (who appears onstage for exactly four paragraphs), then pulls a huge bluff to make the culprit confess.

In the collection’s title story, “Report for a Corpse†(July 1947), a wealthy old woman hires Chambers to find out how her unfaithful husband, whom she’s refused to divorce (at a time when the only ground for divorce under New York law was adultery), plans to kill her. Shadowing the errant husband, Chambers discovers that he’s surreptitiously collected a huge supply of barbiturates.

Visiting his client’s stately home to report to her, he gets to meet the couple’s lovely adopted daughter and apparently has a quickie with her. Soon afterwards the older woman is found dead of an overdose of, you guessed it, barbiturates. Chambers fakes an alibi for the husband and then pins the crime on — well, I’d be a toad if I said more.

With five violent deaths and a plot rooted in events of a dozen years earlier, “The Shoe Fits†(July 1947) leads one to suspect that Kane had begun it as a novel and then, changing his mind, had boiled it down to the length of his other Esquire tales. In Hollywood to act as a $750-a-week technical adviser on a PI epic — perhaps a follow-up to THE BIG SLEEP? — Chambers is offered a bonus by the producer and director of the movie to bodyguard a Nevada casino owner who’s deeply in debt to the Mob and likely to be killed for welshing.

The guy is murdered before Chambers can take on the job but our sleuth suspects that it wasn’t a Mob hit, follows the trail back to New York and three deaths that took place years before, returns to Hollywood and wraps things up as usual. One of the central clues is gibberish except to dyed-in-the-wool New Yorkers and another stands out like W.C. Fields’ nose to anyone who remembers a little high-school German.

In “Suicide Is Scandalous†(June 1948) Chambers’ client is another old lady and his job is to prove that one of her stepdaughters, an unaccountably wealthy woman who according to the evidence shot herself to death in her Park Avenue apartment on a Sunday morning, was actually a murder victim.

If in fact she was murdered, the prime suspects would be the client herself and her other stepdaughter, each of whom inherits half under the dead woman’s will. With the bullet in her head clearly fired from her own gun and with a suicide note in her own handwriting found beside her body, Chambers seems to be up against a stone wall.

But with the help of a penmanship clue borrowed from A HALO FOR NOBODY, and after a fistfight with the murderer, he breaks down the wall and earns his fee.

***

Kane’s Esquire appearances were not limited to short stories. The magazine had published a condensed version of ARMCHAIR IN HELL (January 1948) and also ran condensations of his third, fourth and fifth novels, which I’ll discuss in another column, plus a single stand-alone short story, never collected (“Lost Epilogue,†October 1948).

During the 1950s Kane’s novels were all paperback originals, his short stories appeared usually in Manhunt, and he perfected the oddball narrative style known to his admirers as High Kanese. Perhaps I’ll explore these later too.

Wed 28 Dec 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

HENRY KANE – Who Killed Sweet Sue? Avon, paperback original, 1956. Signet D2575, paperback, January 1965. British title: Sweet Charlie (Boardman, hardcover, 1957).

Here’s an example in which the British title makes a lot more sense than the US edition does. There are maybe a half dozen people named Charles, Charlie, Chas., Charlene, or C. Smith Applegate, Jr. and Sr., but no one named Sue. I can’t have missed her!

The private eye in most of Henry Kane’s novel was a Manhattan-based fellow named Peter Chambers, and though he can mix well enough in sophisticated circles, he’s a guy as tough as they come. And it always amazes me that he’s a pretty good detective too, at least in his earlier cases. You have to keep a close eye on the clues in this one. The smallest detail may matter.

He’s hired twice in the same day by two clients whose interests may overlap, but since the second one, a strip tease dancer who specialty is snakes as part of her act, doesn’t tell him why she’s hiring him, he takes her on also. (Twenty thousand dollars in cash helps make decisions like that very easy.)

The earlier client is a well known British actor now working in the US named Charles Rexy, and yes, he’s known to the tabloids as Sexy Rexy, which is part of his problem. He’s being blackmailed (home movies have been taken) and the stripper may be part of it.

The number of characters that Chambers comes across in the course of is investigation simply grows and grows. If it weren’t for a full page, one paragraph summary about halfway through, a veritable scorecard for all the players, a reader might throw up his or her hands in frustration and dismay. I know; I nearly did. But I’m glad I persevered. The second half of the book, story-wise, is well worth waiting for.

Henry Kane also had a way with words, there’s no doubt about it, and there a certain rhythm that you as a reader have to adjust to, or you’re going to left out in the cold. Luckily for me, I have the beat.

Fri 5 Feb 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

HENRY KANE – Until You Are Dead. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1951. Dell #580, paperback, 1952. Signet S1835, paperback, August 1960.

Of author Henry Kane’s prodigious output of over 60 novels, about half of them featured PI Peter Chambers as the main protagonist. Until You Are Dead is the first of them I’ve read in several years, and it took me a while to get used to his writing style, a combination of quick patter and a uniquely quirky view of the world. Whether that POV was Chambers’ or Kane himself, I do not know.

The story has to do with a jazz musician’s attempt to cut a deal with a mob boss whom he saw kill a man in a night club men’s room. Said jazz musician ends up dead, and it is up to Chambers to find out who and why, even though he doesn’t have a client. Not right away anyway.

Chambers, a guy with an eye for the ladies as he goes, both fires and misfires on the case, which is a medium-boiled affair with a modicum of actual detective work. A potboiler, perhaps, but all in all, once I was in sync with Kane’s style, an interesting and in its own way, an enjoyable reading experience.

Some examples thereof. From pages 85 and 86 of the Signet paperback:

I went to the cabinet and broke out a new bottle of Scotch (here he goes again). I peeled the cellophane off the top and clipped off the cork. I poured into a shot glass and swallowed it neat. I poured again and put the bottle away. 1 held up the glass and looked at amber glistening in the sunlight and mused. People say I drink too much. The hell with them. People say nobody can drink that much. The hell with them, I know people who drink more. People say I’ll have no liver left when I’m old. The hell with them, who wants a liver when you’re old? Literary critics rant. The … (excuse me). Let them rant (between drinks). I like to drink. So far, it agrees with me. When it stops agreeing with me, I’ll listen to the literary critics, as I sorrow under the burden of cirrhosis. There are all kinds of people. It makes for an interesting world. There are people who smoke three packs of cigarettes before they really get going for an evening in the night clubs. There are prime ministers who inhale eighteen fat cigars a day. There are people who buy pornographic books which they read every day except Sunday. There are people who push against people in crowded subways. There are people who play footsie with strangers in the movies. There are people who drink four ice cream sodas at a smack. There are secret eaters of constant pickles. There are people who go for smoked tongue with mustard by the heap. There are people who slush through a pound of cream candies during one chapter of a thick book with significance. There are pistachio nut eaters. There are marijuana smokers. There are opium addicts. There are movie-goers (including matinees). There are people who devote celibate lives to devising instruments of mass destruction. There are soda-pop drinkers. There are frankfurter nuts. There are sun-bathers, vegetable eaters, vitamin girls, hormone boys, sidewalk psychiatrists, neon hunters, nylon oglers, stamp collectors, headline readers, glass crunchers, five-mile hikers, deep breathers, left-handed pitchers, sweepstake winners, golf players, winter swimmers, and guys that make parachute jumps at the age of a hundred and nine. There are even philosophical private detectives.

Me, I like to drink (among other things). So what?

Switching gears on a dime and continuing on, from pages 86 and 87:

I drank. Then I latched on to the phone again. I dialed Information and asked for Cream Baylor’s phone number, I got the number and I called Baylor. Sweetly, I said, “Mr. Baylor, please.”

The girl said, “Who’s calling?”

“Peter Chambers.”

“Peter Chambers of where?”

“Of where?”

“Your firm? Whom are you connected with?”

“I am connected with nobody. Personal.”

“One moment, please.”

I held the receiver away from my ear while the plugs plugged, then I got a new voice, feminine, but just as firm.

“Yes?”

“Mr. Baylor, please.”

“Who’s calling?”

“Peter Chambers.”

“Peter Chambers? Of where?”

“I just went through that routine, sister. This is a personal call.”

“Oh. Whom do you wish to speak with?”

“Same party. Cream Baylor.”

“Your name please?”

“No change. Still Peter Chambers.”

“Thank you. Will you hold on a moment?”

I held on a moment. I lit a cigarette with one hand. I gazed fondly at the liquor cabinet. Then the voice came back. “Mr. Baylor doesn’t seem to know you, sir.”

“May I speak with him, please?”

“He’s very busy right now.”

“Look, it’s important.”

“I’m sorry, sir.”

“Well, can I make an appointment to see him?”

“What is it about, sir?”

“Who’s this? Who’m I talking to?”

“This is his secretary, sir.”

“Look, Miss, I’m a private, uh, a philosophical private detective.”

“Pardon?”

“A private detective.”

“Yes?”

“I’d like to see Mr. Baylor on a case rm employed on. A murder case. A young man by the name of Kermit Teshle. Wm you tell that to him, please? Tell him it’s urgent.”

“One moment, sir.”

I smoked, savagely. I ground out the cigarette. I couldn’t get to the inviting cabinet without leaving the phone. Urgent, I had said to the girl. I lived without a drink.

The voice returned. “Hello?”

“Yes?”

“Mr.Baylor can fit you in two weeks from today, Thursday, at two o’clock ”

“Look, I want to talk to the guy. Now.”

“Sorry, sir. Mr. Baylor is engaged right now.”

“It’s murder.”

“That’s right, sir.”

“Take a message for him, will you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Tell him to go and —”

She hung up on me.

Wed 6 Jun 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I spent a goodly chunk of April on the road, driving to the east coast with many stops along the way, then taking Amtrak from New York to Salem, Massachusetts, where I visited Bob Briney’s grave and conferred with the attorney handling his estate.

He drove me out to Bob’s house, which I hadn’t seen in almost 22 years, and together we went through some of his files. Among them were several manila folders containing letters to Bob from me, hundreds of them, dating as far back as the late Sixties.

Recently I received a huge package in the mail which turned out to contain those letters, returned to me by the attorney. Since then I’ve spent several hours re-reading them. A strange and sort of spooky experience, almost like going back in time to the decades when I was young and, judging from all the projects I was involved in, bursting with energy.

After a few years of corresponding with Bob I got into the habit of passing along to him some of the dreadful lines I had encountered in my reading. Care to sample a few? Here’s one from Harry Stephen Keeler’s The Monocled Monster:

“It was a dark and narrow corridor down which the nurse led Barry Wayne. Cork-paved, his feet and hers made no sound.â€

And another from the king of Malapropia, Michael Avallone:

“Widows who see bachelors like you suddenly running around with women is the curiosity that kills all cats.â€

To commemorate the current celebrations in London I offer this exchange of dialogue from William Ard’s The Sins of Billy Serene:

“Jesus Christ,†Gino said hollowly, “you’re a whore.â€

“And what’d you think I was — Queen Elizabeth?†she asked tartly.

From John Ball of In the Heat of the Night fame:

“The two blacks sprinted out of the store … running like maddened eels.â€

Finally a gem that would have bedecked my own novel Corrupt and Ensnare (1978) if I hadn’t caught it in time. Loren Mensing reflects that Incident A and Incident B “bore the earmarks of the same hand.†At the bottom of the letter in which I shared this gaffe with Bob I found in his handwriting: “And the handiwork of the same mind, no doubt.â€

More than forty years ago I copied for Bob the following paragraph, which is supposed to be the first-person narration of an educated woman. “Sweet, dear, impossible man. I wonder who he’s making love to now. I wish it were me. I have the education and breeding to appreciate a gentleman like he is.†Anyone want to guess who perpetrated it?

I don’t usually go back to old columns of mine months later but a few weeks ago for some unfathomable reason I revisited one that was posted in January 2011. Part of it dealt with a radio director named Fred Essex, now in his nineties, who in a memoir talked about having directed an episode of The Adventures of Ellery Queen in which Ellery was played by Carleton Young, the guest armchair detective was comedian Fred Allen, and the murder “was committed in a radio studio that was supposedly rehearsing a crime program.“

The problem, as I pointed out, is that there’s no known episode during Young’s tenure as EQ where Ellery solved a crime in a radio studio and no episode at any time where Fred Allen was the armchair sleuth.

Among those who happened to read my column was Fred Essex himself, who insisted that his memory hadn’t played him false. In August of last year, Queen expert Kurt Sercu gave us the answer to this conundrum. What Essex remembered was not an EQ episode with Fred Allen as guest sleuth but an episode of The Fred Allen Show (June 6, 1943) which featured an EQ spoof skit with Carleton Young himself playing Ellery and Allen and a couple of his comedy characters as armchair detectives. Vielen Dank, Herr Sercu!

When a writer trying to come across as an authority on the mean streets makes a mistake that his most sheltered readers catch, the egg on the guy’s face just won’t rub off.

In putting together last month’s column I caught a classic howler of this sort in one of the earliest stories of Henry Kane. In “The Shoe Fits†(Esquire, ??? 1947; collected in Report for a Corpse, 1948) private richard Peter Chambers tells us about a gangster who had taken over a top spot “directing traffic from Old Mexico to California, hashish traffic, call it marijuana….â€

No, you did not dream you read that. Kane thinks hash and pot are the same substance! At least he did in 1947 when very few were drug-savvy.

Among the treasures of my library are two signed mint copies of James Ellroy’s first novel, the paperback original Brown’s Requiem (Avon, 1981), which I first read back in the Eighties.

Its protagonist and narrator is Fritz Brown, a lover of classical music (German Romantic composers exclusively) who after being kicked out of the LAPD became a repo man and occasional PI. The plot is a Chandleresque labyrinth — a beautiful cellist, a serial arsonist, golf caddies, corrupt cops, a welfare racket — but the style is closer to Bill Pronzini and, with its dysfunctional family and ceaseless journeys into the past, the mood is closer to Ross Macdonald.

Anyone expecting the telegraphic non-sentences and epic bloodletting of the later Ellroy will be surprised to discover that Requiem is coherently written and minimally violent, although when it comes the violence is pretty gory.

There are some laughably self-indulgent moments, as when Brown treats us to a farrago of irrelevant anecdotes about caddies (or, as they call themselves, loopers) and later — twice in five pages! — to a loony poem he’s composed in a dream.

But it’s a powerful read, and offhand I can’t recall any other non-series PI novel that deserves to stand on the same shelf with Stanley Ellin’s 1958 classic The Eighth Circle. Which, thanks to the alphabetical proximity of their names, is just where it stands in my library!

Thu 10 May 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

During the last months of World War II the editors of Esquire decided to launch a series of short detective stories and invited various mystery writers to create new characters for possible publication in the magazine.

Among the invitees was Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), perhaps the nuttiest author on earth. Harry got miffed at the thought of being asked to “submit a sample like a guy with a tin cup†and demanded $100 in advance. He must have fallen on the floor in shock when Esquire immediately sent him a check, although the editors specified that the advance wasn’t a commitment to accept his submission.

Keeler proceeded to string together a 14,000-word adventure about a barking clock and an astigmatic witness, with a 7½-foot-tall mathematically educated hick from the sticks serving as detective. At first the character was named just that — Abner Hick to be precise — but before sending out the manuscript Keeler prudently changed his name to Quiribus Brown.

When Esquire rejected the story, Keeler yanked Quiribus out of the plot, replaced him with that bedraggled old universal genius Tuddleton T. Trotter (who had starred in Harry’s mammoth extravaganza The Matilda Hunter Murder back in 1931), and added 85,000 more words to the story.

His Spanish publisher Instituto Editorial Reus issued the result as El Caso del Reloj Ladrador (1947). Keeler’s U.S. publisher, the bottom-rung Phoenix Press, put out a shorter version that same year as The Case of the Barking Clock.

Since Phoenix dropped Keeler in 1948, leaving him without a U.S. publisher for the rest of his life, Quiribus never saw the light of print in his native land. But Harry made him the protagonist in The Case of the Murdered Mathematician, issued in 1949 by his London publisher Ward, Lock.

So what new detective was chosen to grace the pages of Esquire? A New York PI named Peter Chambers whose creator was Henry Kane, a lawyer and something of a Chandler wannabee. Chambers narrates his own cases in an idiom, known to connoisseurs as High Kanese, which is worlds removed from Keeler’s style but just as lovably eccentric.

The first six Chambers stories appeared in Esquire between March 1947 and June 1948 and were collected as Report for a Corpse (Simon & Schuster, 1948).

The timing was unfortunate in the sense that the book came out several months after Anthony Boucher was let go as reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle and before he became mystery critic of the New York Times. I’d love to know what Boucher thought of this volume, but it was his predecessor Isaac Anderson who reviewed the book in the Times.

I read the tales a few decades ago but had forgotten them completely when I started to reread them earlier this year. They’re more cleverly plotted than most PI stories during the years Chandler dominated the genre, but there’s nothing truly memorable about any of them and the narration is a pale shadow of what would soon become mature Kanese.

According to just about any print or electronic source you might check, Henry Kane was born in 1918 and is still alive. Apparently neither of these statements is true.

Lawrence Block had several conversations with Kane in the early 1970s and, while preparing a memoir of him for Mystery Scene, did some investigative work that was worthy of his own PI Matthew Scudder. An old girlfriend of Kane’s told Block that “he was most likely born not in 1918 but in 1908.†At least when Block knew him, he “lived on Long Island — Lido Beach, if memory serves — and spent Monday through Friday in an apartment on 34th Street west of Ninth Avenue.â€

Block tells us that he “took his work seriously, and insisted that each page be perfectly typed before he went on to the next one.†He was of Jewish descent but told Block that he “didn’t believe in any of that mumbo-jumbo.â€

His lifestyle was that of the stereotypical PI: a Dexedrine pill every morning, at least a quart of Scotch and a couple of packs of cigarettes a day. “It must have been sometime in the early ’80s that he died,†Block surmises.

Of the eleven Henry Kanes listed in the Social Security Death Index, the one who was born in 1908 and died in 1988 is most likely our man. I would love to have met him, though not necessarily in that smoke-choked apartment.

In his years as conductor of the “Criminals at Large” column for the Times, Anthony Boucher reviewed most of the Kane novels and collections, even though they were published in the unprestigious paperback-original format.

I still recall vividly the time he reviewed one of those novels twice. Its U.S. title was Too French and Too Deadly (Avon pb #672, 1955). In his Times column for December 18, 1955 he called the book “probably enjoyable; Peter Chambers stories are usually amusing, and this one is said to include ‘a locked room within a locked room.’

“But the publishers have chosen to crowd a full-length novel into 122 pages by squeezing 500 words onto a 4-inch by 6-inch page; and squinting one’s way through the book is too much to ask of a reviewer, a reader, or anyone save possibly a Lord’s-Prayer-on-Pinhead engraver.â€

Apparently Kane then sent Boucher a copy of the hardcover British edition, The Narrowing Lust (Boardman, 1956). In his column for June 24, 1956, Boucher reported that “now that it’s legible, it’s also highly readable†and “includes an unusually impossible-seeming locked room problem. It’s a welcome blend of strict detective puzzle and crisp and sexy thriller….â€

In my last column I quoted the late Fred Steiner, composer of the Perry Mason theme: “You look at those old film noir pictures, they’ve always got jazz going for some reason or other.â€

Since then I’ve discovered that this seems to be a classic case of false memory. The point was demonstrated by David Butler in his book Jazz Noir: Listening to Music from Phantom Lady to The Last Seduction (Praeger, 2002) and confirmed by William Luhr in his just published Film Noir (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012):

“Although many neo-noir movies have used single-instrument jazz solos to evoke the film noir era, it is difficult to find a canonical film noir [i.e. one that dates from the Forties or Fifties] that opens in that way. Most used full orchestral scores, as was standard studio practice.â€

It’s only in TV private-eye series like Peter Gunn that jazz became the norm. And, as Lawrence Block points out, the strongest uncredited influence on that landmark series was the novels and stories of Henry Kane — who wound up writing the Peter Gunn tie-in novel (Dell pb #B155, 1960)!

Is this a weird world or what? Luhr’s book is one of the few that discusses in depth both canonical noir and the more recent evocations of the genre, of which perhaps the finest is Chinatown (1974). I recommend it highly to anyone invested in that type of film. And aren’t we all?

Previously on this blog:

A Corpse for Christmas, by Henry Kane. Reviewed by Bill Deeck.

Trinity in Violence, by Henry Kane. A 1001 Midnights review by Art Scott.

The Midnight Man, by Henry Kane. A 1001 Midnights review by Bill Pronzini.

A Corpse for Christmas, by Henry Kane. Reviewed by Steve Lewis.

Until You Are Dead, by Henry Kane. Reviewed by Steve Lewis.

A long quote from the latter book is included as a big chunk of the review.

Sun 10 Oct 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

HENRY KANE – A Corpse for Christmas. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1951. Hardcover reprint: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, November 1951. Paperback reprints: Dell 735, 1953; Zenith ZB-19, 1959, as The Deadly Doll; Signet D2877, 1966, as Homicide at Yuletide; Lancer 75261, 1970s? Previously a two-part serial in Esquire, December 1949 & January 1951.

As all of you — or at least the three people who read these reviews out of a misguided urge to get your money’s worth from this magazine — know, I strive for balance here. That is to say, I endeavor to work in at least one tough P.I. novel every other column.

This one almost didn’t make it, since fantasy is what the author starts with. I mean, of the six females encountered by the detective, four of them are hot for his body immediately. His client would be, but she is aware he lusts after her so she needn’t bother. Only a landlady shows no desire, perhaps because she’s unprepossessing and it would embarrass the detective.

Acting in behalf of his client, another private eye in jail on several traffic charges, Peter Chambers discovers a man, with wine-red hair and beard of the same color, shot to death. Holding the murder weapon is a young lady, who of course didn’t do it.

A gangster looking for some jewels possessed by the dead man is the client of Chambers’s client, and there are various former wives of the dead man whose income he was going to cut off but who didn’t mind that, or so they say.

Chambers investigates on Christmas Eve and Christmas and identifies the murderer, who was fairly obvious at least to this reader.

What kept me reading was Kane’s obvious love of the language and Chambers’s sense of humor. Kane has a delightful style, although I still haven’t figured out what a “saltatory mattress” might be. Maybe he’ll explain it in his other books, which I’ll be looking for.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 2, Spring 1989.