THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

MILWARD KENNEDY – Poison in the Parish. Victor Gollancz, UK, hardcover, 1935. No US edition.

After a late death certificate and six months of rumor, the odious Miss Tomlin, who died at the Guest House — “a boarding-house where the inmates pay high for insufficient fare in order to avoid damage to their gentility” — is disinterred.

Since an unusual amount of arsenic is found in the body, the police suspect murder. To get help in their investigations, the Chief Constable asks Francis Anthony to listen to the local gossip and report on his findings.

Idled by a game leg and messed up intestines, Anthony at first is loath to take part. Only the fact that his beloved niece is enamored of Miss Tomlin’s nephew, who, along with his sister, may be a suspect, induces Anthony to accede to the Chief Constable’s wishes. Anthony hopes to prove that Miss Tomlin’s death was either accident or suicide.

In his dedication, the author says to a “friend”: “In your omniscient superiority you have pointed out that in all my books, of which you have read so few, the characters are unpleasant: here is an attempt at something different.”

The characters are quite pleasant, although [one] Miss Figgis is not exemplary. Fair play is lacking, but the astute reader — not that any such bother to peruse my reviews — will note an early oddity and begin building a case against one individual.

Well written and amusing.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

Bibliographic notes: Of the sixteen books published by the author (Milward Kennedy Burge, 1894-1968), including one as by Robert Milward Kennedy, this seems to have been the only mystery tackled by Francis Anthony. Two were cases solved by Inspector Cornfold; Sir George Bull was the sleuth of record in another pair.

Kennedy also wrote two books as by Evelyn Elder, one of which, Murder in Black and White, has recently been reprinted in the US by Ramble House.

ROUND ROBIN MURDERS:

The Floating Admiral (1931) and Double Death (1939)

by Curt J. Evans

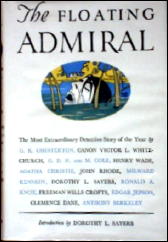

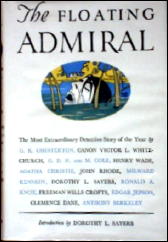

In its ongoing attempt seemingly to wring every last pound of profit out of the Agatha Christie literary estate, HarperCollins has recently reprinted The Floating Admiral, the collaborative detective novel (originally published in 1931) by fourteen members of the then recently formed Detection Club (each writing a successive chapter).

Although Agatha Christie’s contribution is a chapter of eight pages (in my 1979 Gregg Press edition) — 3% of the book — she gets top billing, with only Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton (the latter of whom contributed, by his own admission, a strictly ornamental prologue of five pages) also being mentioned by name, in much smaller letters. Such are the publishing perks of fame and continued books sales!

To my mind, the detective novel, requiring as it does the most scrupulous planning, is not really a form that is receptive to “round robin” treatment. Case in point: The Floating Admiral. Overloaded with complications from too many eager hands, the tale in my opinion begins to take on water and sink well before reaching its conclusion (tellingly entitled by Anthony Berkeley, “Cleaning Up the Mess”).

Nevertheless, if one is interested in authors of Golden Age detective fiction, The Floating Admiral is in many ways quite interesting, whatever its artistic failings.

Things go pretty well for the first five chapters (written by Canon Victor L. Whitechurch, G.D.H. and Margaret Cole, Henry Wade, Agatha Christie and John Rhode), with the authors refraining from over-elaboration. Unfortunately the calmly floating boat is upset by water violently churned by Milward Kennedy (his chapter, which follows Rhode’s “Inspector Rudge Begins to Form a Theory” is impertinently entitled “Inspector Rudge Thinks Better of It” — the good Inspector should not have).

Dorothy L. Sayers tries to straighten everything out that had tangled with a thirty-seven page chapter but she only makes things worse.

Ronald A. Knox’s chapter, “Thirty-Nine Articles of Doubt” (Chapter Eight) warningly raises thirty-nine problematical points that have accumulated for the authors following him to consider and Freeman Wills Crofts in Chapter Nine politely notes that, among other things, the body (allegedly of the admiral of course) was never adequately identified or an inquest arranged. But all to little avail.

Clemence Dane complains in her notes to her Chapter Eleven, the penultimate chapter, that the mystery has become “quite inexplicable to me” — and she likely has not been alone in that sentiment over the years.

Anthony Berkeley’s conclusion has been praised heartily by over-generous critics. I deem more like the curate’ egg — good in spots but essentially rotten. But to be fair to the poor fellow, he was handed the devil of a job.

The fun for me in reading The Floating Admiral is not in reading a cogently plotted detective novel (it simply isn’t one), but in seeing the narrative approach each author takes in his/her chapter:

â— G. K. Chesterton writes rich prose.

â— Canon Whitechurch introduces a charming vicar.

â— Henry Wade develops appealing and credible relationships among his policemen.

â— Out of the blue, Agatha Christie introduces a garrulous, gossipy lady innkeeper.

â— John Rhode discusses tidal movements (the admiral was floating after all) and sympathetically expands the role of the retired petty officer, Neddy Ware.

◠Milward Kennedy overcomplicates the story, as does Dorothy L. Sayers (the ingenious Sayers should have been given the opening chapter — she and Kennedy both clearly wanted it).

â— Ronald A. Knox makes a long list.

â— Freeman Wills Crofts checks alibis and has his inspector travel by train.

â— In his notes to his chapter, Knox amusingly declares, “I once laid it down that no Chinaman should appear in a detective story. I feel inclined to extend the rule so as to apply to residents in China. It appears that Admiral Penistone, Sir W. Denny, Walter Fitzgerald, Ware and Holland are all intimate with China, which seems overdoing it.”

In her recent Guardian review of the new edition of The Floating Admiral, Laura Wilson deems Agatha Christie proposed solution for the tale “as you would expect, the most ingenious” of all the solutions. Certainly it’s more tricksy than, say, the solution proffered by John Rhode (without a complicated murder means, Rhode is unable to play to his greatest strength here). It’s also absolutely absurd.

Here’s how Christie envisioned the state of affairs in the Admiral’s household (*** SPOILER *** to Christie’s proposed solution follows, obviously):

The Admiral’s niece is really his Uncle’s nephew masquerading as the niece. He has been doing this in his Uncle’s household for weeks, and is able to get away with it because he “has been an actor at one time” (that Golden Age crutch for the unlikely accomplishment of great disguises) and because the Admiral has not seen the niece since she was a child (he has seen the nephew more recently, however). The servants are fooled as well, as are the various beaux of the neighborhood, whom the nephew “takes an artistic pleasure” in vamping. (*** END SPOILER ***)

Ingenious or rather ridiculous? You decide for yourself, but I know what I think.

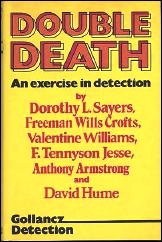

On the whole, I much preferred Double Death, a round robin novel with chapters by Dorothy L. Sayers, Freeman Wills Crofts, Valentine Williams, F. Tennyson Jesse, Anthony Armstrong and David Hume that originally appeared in the Sunday Chronicle in (I believe) 1936 and was published in book form by Victor Gollancz.

It is often stated to be a Detection Club production, but I do not see how this could be, since only two of the six writers, Sayers and Crofts, were members of the Detection Club.

In her introductory chapter to Double Death, Sayers sets up a compelling possible domestic poisoning situation, followed by a death at a railway station, at the evocatively named town of Creepe.

Freeman Wills Crofts embroiders on this opening situation ably (he even provides a stunning map of Creepe and Creepe station), as does Valentine Williams, though the latter is more known for his “Clubfoot” thrillers than his (underrated) detective novels. Unfortunately the later authors are less concerned with cluing, so that as a fair play mystery the tale ends up rather a bust (especially if you read the silly prologue, added later).

However, the writing and overall emotional situation remains compelling throughout Double Death, thus making the tale more of a success than the The Floating Admiral.

It’s interesting to note that in Double Death, written in the mid-thirties, all the authors are concerned with maintaining love interest; whereas in The Floating Admiral all the characters are sticks in whom one could not be expected take the slightest interest (well, there’s the vamping transvestite nephew, as envisioned by Christie).

As the 1930s progressed, the Golden Age detective novel began to put more emphasis on emotional situations and less on ratiocination. In the end, it is this shift in emphasis that makes Double Death more interesting than The Floating Admiral, in my view. Admiral depends for artistic success on detection and too many hands on deck sink the craft.

Yet with less than half the people involved, Double Death might have managed to work as a true fair play detective novel. Certainly Sayers, Crofts and to a lesser extent Valentine Williams made an admirable start of it.

I rather wish the novel could have been kept a collaboration simply of two: Sayers and Crofts. The two authors corresponded over the opening chapter of Double Death in the spring of 1936, with Sayers requesting and Crofts supplying pertinent points of railway station detail.

Sayers had already written her railway timetable novel The Five Red Herrings (1931) as a sort of homage to Crofts’ Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930) — these two brilliant books continue to stand today as the ne plus ultra of railway timetable mysteries. Double Death in their hands might well have been a classic product of the Golden Age. As it is, it is still a good read.

150 Favorite Golden Age British Detective Novels:

A Very Personal Selection, by Curt J. Evans

Qualifications are the writers had to publish their first true detective novel between 1920 and 1941 (the true Golden Age) and be British or close enough (Carr). So writers like, say, R. Austin Freeman, Michael Gilbert and S. S. Van Dine get excluded.

I wanted to get outside the box a bit and so I’m sure I made what will strike some as some odd choices. This is a personal list. If I were making a totally representative list John Dickson Carr’s The Three Coffins, Nicholas Blake’s The Beast Must Die, Michael Innes’ Lament for a Maker, Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case, Sayers’ Gaudy Night, etc., would all be there). And lists evolve over time. It’s highly likely, for example, that as I read more of Anthony Wynne and David Hume, for example, they would get more listings.

Also I excluded great novels like And Then There Were None, The Burning Court and Trial and Error, for example, because I felt like they didn’t fully fit the definition of true detective novels. In any list list I would make of great mysteries, they would be there.

If people conclude from this list that my five favorite Golden Age generation British detective novelists are Christie, Street, Mitchell, Carr and Bruce, that would be fair enough, though I must add that they were very prolific writers, so more listings shouldn’t be so surprising.

The 150 novels break down by decade as follows:

1920s 9 (6%)

1930s 87 (58%)

1940s 30 (20%)

1950s and beyond 24 (16%)

A pretty graphic indicator of my preference for the 1930s!

Also, of the 61 writers, I believe 40 are men and 21 women — I hope my count is right! — which challenges the conventional view today that most British detective novels of the Golden Age were produced by women. Of these, 31, or just over half, eventually became members of the Detection Club. I exclude a few of these luminaries, such as Ronald Knox and Victor Whitechurch (am I anti-clerical?!).

JOHN DICKSON CARR (8)

The Crooked Hinge (1938)

The Judas Window (1938) (as Carter Dickson)

The Reader Is Warned (1939) (as Carter Dickson)

The Man Who Could Not Shudder (1940)

The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941)

The Gilded Man (1942) (as Carter Dickson)

She Died a Lady (1944) (as Carter Dickson)

He Who Whispers (1946)

â— It’s probably sacrilege not to have The Three Coffins on the list (especially when you have The Gilded Man!), but when I read Coffins I enjoyed it for the horror more than the locked room, which seemed overcomplicated too me (need to reread though).

AGATHA CHRISTIE (8)

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1926

Murder at the Vicarage 1930

The ABC Murders 1936

Death on the Nile 1937

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe 1940

Five Little Pigs 1942

A Murder Is Announced 1950

The Pale Horse 1961

â— Haven’t reread The ABC Murders recently; was somewhat disappointed with Murder on the Orient Express when rereading and thus excluded from the list. And Then There Were None regretfully excluded, because I wasn’t sure it really qualifies as a detective story (there’s not really a detective and the solution comes per accidens).

GLADYS MITCHELL (8)

Speedy Death (1929)

The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop (1929)

The Saltmarsh Murders (1932)

Death at the Opera (1934)

The Devil at Saxon Wall (1935)

St. Peter’s Finger (1938)

The Rising of the Moon (1944)

Late, Late in the Evening (1976)

â— A true original, but not to everyone’s taste.

JOHN RHODE (MAJOR CECIL JOHN CHARLES STREET) (8)

The Davidson Case (1929)

Shot at Dawn (1934)

The Corpse in the Car (1935)

Death on the Board (1937)

The Bloody Tower (1938)

Death at the Helm (1941)

Murder, M.D. (1943) (as Miles Burton)

Vegetable Duck (1944)

â— The Golden Age master of murder means, underrated in my view.

LEO BRUCE (8)

Case for Three Detectives (1936)

Case with Ropes and Rings (1940)

Case for Sergeant Beef (1947)

Our Jubilee is Death (1959)

Furious Old Women (1960)

A Bone and a Hank of Hair (1961)

Nothing Like Blood (1962)

Death at Hallows End (1965)

â— In print but underappreciated, he carried on the Golden Age witty puzzle tradition in a tarnishing era for puzzle lovers.

J. J. CONNINGTON (5)

The Case With Nine Solutions (1929)

The Sweepstake Murders (1935)

The Castleford Conundrum (1932)

The Ha-Ha Case (1934)

In Whose Dim Shadow (1935)

â— An accomplished, knowledgeable puzzler.

E.C.R. LORAC (EDITH CAROLINE RIVETT) (5)

Death of An Author (1935)

Policemen in the Precinct (1949)

Murder of a Martinet (1951)

Murder in the Mill-Race (1952)

The Double Turn (1956) (as Carol Carnac)

â— Has taken a back seat to the Crime Queens, but was very prolific and often quite good (my favorites, as can be seen, are more from the 1950s, when she became a little less convention bound).

E. R. PUNSHON (5)

Genius in Murder (1932)

Crossword Mystery (1934)

Mystery of Mr. Jessop (1937)

Ten Star Clues (1941)

Diabolic Candelabra (1942)

â— Admired by Sayers, this longtime professional writer (he published novels for over half a century) is underservingly out of print.

MARGERY ALLINGHAM (4)

Death of a Ghost (1934)

The Case of the Late Pig (1937)

Dancers in Mourning (1937)

More Work for the Undertaker (1949)

â— Her imagination tends to overflow the banks of pure detection, but these are very good, genuine puzzles.

G. D. H. and MARGARET COLE (4)

Burglars in Bucks (1930)

The Brothers Sackville (1936)

Disgrace to the College (1937)

Counterpoint Murder (1940)

â— Clever tales by husband and wife academics not altogether justly classified as “Humdrums.”

FREEMAN WILLS CROFTS (4)

The Sea Mystery (1928)

Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930)

The Hog’s Back Mystery (1933)

Mystery on Southampton Water (1934)

â— The “Alibi King,” he’s more paid lip service (particularly for genre milestone The Cask) than actually read today, but at his best he is is worth reading for puzzle fans.

NGAIO MARSH (4)

Artists in Crime (1938)

Seath in a White Tie (1938)

Surfeit of Lampreys (1940)

Opening Night (1951)

â— Art, society and theater all appealingly addressed by a very witty writer, with genuine detection included.

DOROTHY L. SAYERS (4)

Strong Poison (1930)

The Five Red Herrings (1931)

Have His Carcase (1932)

Murder Must Advertise (1933)

â— As can be guessed I prefer middle period Sayers — less facetious than earlier books, but also less self-important than later ones.

HENRY WADE (4)

The Dying Alderman (1930)

No Friendly Drop (1931)

Lonely Magdalen (1940)

A Dying Fall (1955)

â— Very underrated writer — some other good works (Mist on the Saltings, Heir Presumptive) were left out because they are more crime novels.

JOSEPHINE BELL (3)

Murder in Hospital (1937)

From Natural Causes (1939)

Death in Retirement (1956)

â— Far less known than the Crime Queens, but a worthy if inconsistent author.

NICHOLAS BLAKE (3)

A Question of Proof (1935)

Thou Shell of Death (1936)

Minute for Murder (1949)

â— His most important book in genre history is The Beast Must Die, but I prefer these as puzzles.

CHRISTIANNA BRAND (3)

Death in High Heels (1941)

Green for Danger (1945)

Tour de Force (1955)

â— One of the few who can match Christie in the capacity to surprise while playing fair.

JOANNA CANNAN (3)

They Rang Up the Police (1939)

Murder Included (1950)

And Be a Villain (1958)

â— Underrated mainstream novelist who dabbled in detection.

BELTON COBB (3)

The Poisoner’s Mistake (1936)

Quickly Dead (1937)

Like a Guilty Thing (1938)

â— Almost forgotten, but an enjoyable, humanist detective novelist (B. C. worked in the publishing industry and was the son of novelist Thomas Cobb, who also wrote mysteries)

JEFFERSON FARJEON (3)

Thirteen Guests (1938)

The Judge Sums Up (1942)

The Double Crime (1953)

â— A member of the famous and talented Farjeon family (both his father Benjamin and sister Eleanor were notable writers), he wrote mostly thrillers but produced some more genuine detection.

ELIZABETH FERRARS (3)

Give a Corpse a Bad Name (1940)

Neck in a Noose (1942)

Enough to Kill a Horse (1955)

â— Came in at the tail-end of the Golden Age, like Brand, though she was more prolific (and not as good). She started with an appealing Lord Peter Wimsey knock-off (Toby Dyke), but eventually helped found the more middle class and modern “country cottage” mystery (downsized from the country house).

CYRIL HARE (3)

When the Wind Blows (1949)

An English Murder (1951)

That Yew Trees Shade (1954)

â— Another one who came in near the end of the Golden Age proper, his best is considered to be Tragedy at Law (see P. D. James), but I like best the tales he produced in postwar years.

R. C. WOODTHORPE (3)

The Public School Murder (1932)

A Dagger in Fleet Street (1934)

The Shadow on the Downs (1935)

â— A surprisingly underrated writer, witty and clever in the the way people like English mystery writers to be (why has no one reprinted him?).

ROGER EAST (2)

The Bell Is Answered (1934)

Twenty-Five Sanitary Inspectors (1935)

â— Another mostly forgotten farceur of detection.

GEORGE GOODCHILD & BECHHOFER ROBERTS (2)

Tidings of Joy (1934)

We Shot an Arrow (1939)

â— Working together, these two authors (one, Goodchild, a prolific thriller writer) produced some fine detective novels (their best-known works are a pair based on real life trials).

GEORGETTE HEYER (2)

A Blunt Instrument (1938)

Detection Unlimited (1953)

â— Better known for her Regency romances (still read today), Heyer produced some admired exuberantly humorous (if a bit formulaic) detective novels (plotted by her husband).

ELSPETH HUXLEY (2)

Murder on Safari (1938)

Death of an Aryan (1939)

â— After a decent apprentice genre effort, this fine writer produced two fine detective novels, interestingly set in Africa, with an excellent series detective.

MICHAEL INNES (2)

The Daffodil Affair (1942)

What Happened at Hazelwood (1946)

â— So exuberantly imaginative, he is hard to contain within the banks of true detection, but these are close enough, I think, and I prefer them to his earlier, better-known works.

MILWARD KENNEDY (2)

Death in a Deck Chair (1930)

Corpse in Cold Storage ((1934)

â— A neglected mainstay of the Detection Club, hardly read today.

C. H. B. KITCHIN (2)

Death of My Aunt (1929)

Death of His Uncle (1939)

â— These are fairly well-known attempts at more literate detective fiction, by an accomplished serious novelist.

PHILIP MACDONALD (2)

Rynox (1930)

The Maze (1932)

â— A writer who often stepped into thriller territory (and produced some classics of that form), he produced with these two books closer efforts at true detection (indeed, the latter is a pure puzzle)

CLIFFORD WITTING (2)

Midsummer Murder (1937)

Measure for Murder (1941)

â— Clever efforts by an underappreciated author.

FRANCIS BEEDING

He Should Not Have Slipped! (1939)

â— About the closest I would say that this author (actually two men) came to full dress detection.

ANTHONY BERKELEY

Not to be Taken (1938)

â— A true detective novel and first-rate village poisoning tale by this important figure in the mystery genre, who often tweaked conventional detection.

DOROTHY BOWERS

The Bells of Old Bailey (1947)

â— Best of this literate lady’s detective novels, her last before her untimely death.

CHRISTOPHER BUSH

Cut-Throat (1932)

â— Prolific writer who is not my favorite, but I liked this one, with its clever alibi problem.

A. FIELDING

The Upfold Farm Mystery (1931)

â— Uneven, prolific detective novelist, but this one has much to please.

ROBERT GORE-BROWNE

Murder of an M.P.! (1928)

â— One of my favorite 1920s detective novels, by a mere dabbler in the field.

CECIL FREEMAN GREGG

Expert Evidence (1938)

â— Surprisingly cerebral effort by a “tough” British thriller writer.

ANTHONY GILBERT

Murder Comes Home (1950)

â— My favorite books by this author tend to be more suspense than true detection.

JAMES HILTON

Murder at School (1931)

â— Good foray into detection by well-regarded straight novelist.

RICHARD HULL

The Ghost It Was (1936)

â— About the closest I would say that this crime novelist came to detection.

DAVID HUME

Bullets Bite Deep (1932)

â— Though this series later devolved into beat ’em up thrillers, this first effort has genuine detection (and American gangsters). More reading of this author’s other series may yield additional results.

IANTHE JERROLD

Dead Man’s Quarry (1930)

â— One of the two detective novels by a forgotten member of the Detection Club, more a mainstream novelist (though forgotten in that capacity as well).

A. G. MACDONELL

Body Found Stabbed (1932) (as John Cameron)

â— Detective novel by writer better known for his satire.

PAUL MCGUIRE

Burial Service (1939)

â— Mostly forgotten Australian-born writer of detective fiction, mostly set in Britain. This tale, his finest, is not. It one of the most original of the period.

JAMES QUINCE

Casual Slaughters (1935)

â— A very good, virtually unknown village tale.

LAURENCE MEYNELL

On the Night of the 18th…. (1936)

â— More realistic detective novel for the place and period, in terms of its depiction of often unattractive human motivations, by a writer who veered more toward thrillers and crime novels.

A. A. MILNE

The Red House Mystery (1922)

â— A well-known classic, mocked by Chandler — but, hey, what a sourpuss he was, what?

EDEN PHILLPOTTS

The Captain’s Curio (1933)

â— Counted because his true detection started in the Golden Age. His best work, however, is found in crime novels (and straight novels)

E. BAKER QUINN

One Man’s Muddle (1937)

â— A strikingly hardboiled tale by a little-known author who was written of on this website fairly recently.

HARRIET RUTLAND

Knock, Murderer, Knock! (1939)

â— Mysterious individual who wrote three acidulous detective novels. This is the first, a classic spa tale.

CHRISTOPHER ST. JOHN SPRIGG

The Perfect Alibi (1934)

â— A fine farceur of detection, whose genre talent was purged when he became a humorless Stalinist ideologue (he was killed in action in Spain).

W. STANLEY SYKES

The Missing Moneylender (1931)

â— Controversial because of comments about Jews (as the title should suggest), yet extremely clever.

JOSEPHINE TEY

The Franchise Affair (1948)

â— Genuine detection, though veering into crime novel territory (and veering very well, thank you).

EDGAR WALLACE

The Clue of the Silver Key (1930)

â— One of the closest attempts at true detection by the famed thriller writer.

ETHEL LINA WHITE

She Faded Into Air (1941)

â— See Edgar Wallace. A classic vanishing case, with some of the author’s patented shuddery moments.

ANTHONY WYNNE

Murder of a Lady (1931)

â— Fine locked room novel by an author who tended to be too formulaic but could be good (can probably add one or two more as I read him).

Editorial Comment: Coming up soon (as soon as I can format it for posting) and covering some of the same ground as Curt’s, is a list of “100 Good Detective Novels,” by Mike Grost. The emphasis is also on detective fiction, so obviously some of the authors will be the same as those in Curt’s list, but Mike doesn’t restrict himself to British authors, and the time period is much wider, ranging from 1866 to 1988, and the actual overlap is very small.

While I’ve been tending to other matters and haven’t been able to spend much time with Mystery*File this month, British mystery fan and bookseller Jamie Sturgeon has continued to send me examples of maps in mysteries as he’s come across them. I’ve been collecting some of my own, but where they are at the moment, I don’t know. (I’m a bit unorganized at the moment.)

Rather than wait for me to add mine to his to create one long entry, I’ve finally decided to run only the four that he’s sent me most recently.

First, he says, how about this double one from Fatal Friday by Francis Gerard?

Fatal Friday (Rich, 1937, hc) [Chief Insp. (Supt.) Sir John Meredith; England] Holt, 1937.

Next, he went on to say, perhaps a day or so later, there’s this one in Riot Act by R Philmore:

Riot Act (Gollancz, 1935, hc) [C. J. Swan; England]

Here’s one of the more elaborate maps Jamie says he’s ever seen in a crime novel, one that he sent me while my computer was down. It comes from Angel in the Case by Evelyn Elder (Milward Kennedy), a very scarce book. Some other Methuen books of the period have these maps on the front endpapers as well.

Angel in the Case (Methuen, 1932, hc) [England]

And here’s a map from another Methuen title,The Pressure Gauge Murder, by F.W.B. von Linsingen, his only mystery:

The Pressure-Gauge Murder (Methuen, 1929, hc) [South Africa] Dutton, 1930.

— Bibliographic information taken from

Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

[UPDATE] 10-25-07. The British contingent of crime authors didn’t have a monopoly on maps in mysteries, of course. Bruce Grossman sent this one along, taken from Ellery Queen’s The Dutch Shoe Mystery. In particular, it’s from the softcover edition of Otto Penzler’s reprint, so we’re assuming that it’s the same as the one in the original First Edition.

The Dutch Shoe Mystery (Stokes, 1931, hc; Gollancz, UK, 1931) [Ellery Queen; New York City, NY]