Search Results for 'Ross Macdonald'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 20 Feb 2022

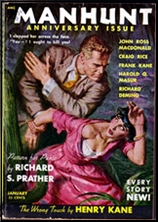

ROSS MACDONALD. “Guilt-Edged Blonde.†Lew Archer. Short story. First appeared in Manhunt, January 1954, as by John Ross Macdonald. Reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, February 1974. Collected in The Name Is Archer (Bantam, paperback, 1955), also as by John Ross Macdonald. Two stories were added to the collection when it was reprinted by Mysterious Press as Lew Archer: Private Investigator in 1977 under the name Ross Macdonald. Reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carrol & Graf, 1988), and in Hard-Boiled: An Anthology of American Crime Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini & Jack Adrian (Oxford Press, 1995). Film: Le loup de la côte ouest (The Wolf of the West Coast), France, 2002. [James Faulkner played protagonist “Lew Millar.â€]

PI Lew Archer is hired for a six day job as a bodyguard for a man who is afraid to leave his house after receiving a phone call that morning. He’s met at the airport by the man’s brother, but the job doesn’t last all that long. When they reach the house, they find his client shot and dying outside on the lawn and a blonde-haired girl driving away in a hurry.

After Archer persuades the brother to pay him to stay on the case, he learns that the dead man had a past. He’d been a treasurer for the mob in his younger days, and it’s apparent that his past had finally caught up with him. The brother, though, is also clearly trying to cover up for the girl.

After tracking down the girl and learning what she tells him, Archer finds himself unlucky with a client a second time. He’s also been shot, and Archer finds him dying outside his home. I won’t go into details, but this is an early version of the stories involving dysfunctional families and their secrets that Ross Macdonald became famous for, and even as short as it is, it’s one told well.

Sun 10 Mar 2019

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

ROSS MACDONALD – The Goodbye Look. Lew Archer #15. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, April 1969. Bantam, paperback; 1st printing, June 1970. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and soft.

Published toward the end of the Lew Archer series, The Goodbye Look had a strong feeling of weariness to it when I read it this past week, that and a sense of déjà vu, as if Macdonald were repeating in it many of the same themes he’d already gone through several times before.

It begins when Archer is hired by a lawyer to find an old gold box that has just been stolen from the family of one of his long time clients. His family and theirs are close — so close, in fact, that not only do they live across the street from each other, but the lawyer’s daughter is engaged to be married to the son of the couple for whom he’s been working for so long.

One strong suspect is the son, a college student who is a very emotionally disturbed young man, and one possibly important factor is that he has recently been taking up with an older woman. A private detective has also been seen in town looking for someone, and when Archer finds his dead body in a car on the beach, the case begins in earnest.

And as is always true in Lew Archer’s cases, the problems that exist in the present have long-standing roots in the past. Lost loves and lost lives, intricately interlaced with relationships known and unknown between (in this case) three if not four families.

I always get a pervasive feeling of melancholy, of dark clouds above, whenever I read one of Macdonald’s books, no matter how sunny the Southern California sky may be. The Goodbye Look is no exception. Archer may make his way from San Diego to Pasadena and back several times in this book, but the case itself he always has with him. It is part of him, and he won’t let go.

Tue 19 Sep 2017

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

ROSS MACDONALD – Black Money. Lew Archer #14. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1966. Reprinted many times, including: Bantam F3320, paperback, 1967. Warner, paperback, August 1990. Contained in Ross Macdonald: Four Late Novels (The Library of America, hardcover, 2017).

It’s good to see Lew Archer back in print [as of 1990]. There were quite a few of his books that I never read when they first came out, although I think I have them all, mostly in book club editions. Given the opportunity to catch up on them now [that Warner has begun reprinting them], I realize I’d forgotten how little of Archer himself gets into these books, with no real information on his life at all, or even his personal thoughts.

He’s hired here to investigate the new man in Ginny Fallon’s life, with his client the rich young man who always thought he’d marry her, but who now sees her being stolen away by a phony Frenchman (he thinks) with the savoir faire he never had, and never will. Ginny’s father was a suicide victim seven years before, and of course it’s connected.

The other thing I’d also forgotten is Macdonald’s overwhelming reliance on similes, metaphors and other literary comparisons to describe almost everything. It’s not done here to the point of self-parody yet, but it seems awfully close at times. As for the mystery itself, it is (as always) chilling, deep and complex. Macdonald does not rely on coincidence as a plot device, and the roots of the crimes in this book are (as always) twisted and embedded far back into the past.

FOOTNOTE: Some of Macdonald’s similes work really well, some don’t. One that didn’t, at least for me, comes from page 8: “The white and purple flowers on the brush gave out a smell like the slow breath of sunlight.” It sounds great, but what does it mean? On the other hand, here’s a quote from page 178 which might serve as Archer’s family motto: “Never sleep with anyone whose troubles are worse than your own.” (This one I like.)

— Reprinted from

Mystery*File #23,, July 1990.

Wed 1 Mar 2017

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[35] Comments

ROSS MACDONALD – The Chill. Lew Archer # 11. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1963. Paperback reprints include: Bantam F2913, 1965; Warner, July 1990; Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1996.

Ross Macdonald is considered one of the finest writers of private eye fiction of all time, and rightly so. The Chill is both tightly plotted and smoothly laid out for the reader, who sees the story through one set of eyes, those of private eye Lew Archer only. One might wish that he would convey everything he thinks to the reader, but for better or worse, he does not.

This leaves it up to the reader to interpret people and events at the same time Archer does, or decide to wait until the end, when, at least in The Chill, there is a seismic shift at work, one that once it has clicked into place, will make sudden sense out of what till then had been a huge and unmanageable set of connected coincidences. This is definitely not the case. Macdonald knew exactly what he was doing when he wrote this book, every inch of the way.

Which begins with Archer being hired by a distraught young man to find his newlywed wife, who seems to have run out on him before their marriage has even been consummated. That’s the easy part. Before locating her, no more than a simple day’s work, Archer runs across several other people who had recently come in contact with her in one way or another, including several academics, one of whom briefly toys with hiring him herself; a man who may or may not be the girl’s father; plus a large group of other miscellaneous lovers, wives and mothers, some incidental, most not, all sharply described and delineated.

One really does need a scorecard to read this densely written and populated book, as the story only escalates from there. Once found, the missing woman then comes very close to being booked for murder. Archer does not think she did it, and not wishing to give up on the case, he needs to find another client, and soon, which luckily he manages to do, and very quickly.

The case takes him geographically from a small town on the California coast to Chicago and Reno and back to Pacific Point before it is done, and chronologically back 20 years or more, with several murders having occurred along the way, some of them “solved,” but perhaps not all.

One of the themes of the book, to me, is one of Zeno’s ancient Grecian paradoxes, which as recounted by Aristotle, goes something like this:

“In a race, the quickest runner can never overtake the slowest, since the pursuer must first reach the point whence the pursued started, so that the slower must always hold a lead.”

Which in everyday language, I take to mean: “No matter how fast you go, you’ll never get there.” Sounds like pure noir to me.

Mon 10 Feb 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

ROSS MACDONALD – The Instant Enemy. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1968. Reprinted many times.

In many ways The Instant Enemy is typical of Macdonald’s entire output, in that the emphasis is on story and plot, and the personality of the detective, one Lew Archer, hardly ever enters into it.

Archer, in other words, is an observer, and we never get much of an insight into what makes him tick. One exception I noted was on page 112 (in the Warner paperback edition I read), where the possibility of getting paid $100,000 jars Archer into the unexpected realization that maybe he might even retire.

That’s probably a million dollars in today’s money, and he feels pretty good about the idea. The moments lasts for only a page, though, and then it’s back to the case on hand. It starts out simply enough — he’s hired to bring back a runaway daughter who’s gone off with a psycho boy friend with a sawed-off shotgun.

Things are never that simple in a Ross Macdonald book, however, and soon all sorts of entanglements with the past begin to emerge, like pulling a root out of a sewer pipe and finding you’re dragging the whole tree out with it. If trees had Oedipus fixations, I think the analogy would be complete. (See page 146.)

Although Instant Enemy is much like all of Macdonald’s other books, and the ending is absolutely terrific, I don’t think this is one of his better ones. (Those of you you’ve read them all recently, please feel free to contradict me on this.) I think it may be the pacing. It’s relentless; it doesn’t give up for a minute; and if you’re so minded, it could become downright monotonous.

Archer is on the go from the beginning of the book to the end. When he’s tired for a moment, he pulls over to a motel and sleeps for a couple of hours, and then he’s on the road again. I think a good many readers are going to feel the need to pull over themselves, right about the three-quarters mark.

If I’m right about this, and maybe I’m not, second-rate Macdonald is still number-one goods, but in this particular case, the really prime stiff is all at the end. People who prefer the light frothy sort of mystery simply aren’t going to get there.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 37, no date given, slightly revised.

Sat 20 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Covers ,

Reviews[8] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

ROSS MACDONALD – The Zebra-Striped Hearse. A. A. Knopf, hardcover, 1962. Bantam F2715, paperback reprint; 1st printing, January 1964. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including those seen below.

If you somehow missed Ross Macdonald’s The Zebra-Striped Hearse in its hardcover edition or in one of the previous twelve (!) Bantam printings, you get another chance, for that publisher has reprinted it again, after a four-year hiatus.

Because this is one of the best in an outstanding series of private-eye novels, it is a book you shouldn’t miss. You’ll find many elements taken from the author’s own life and placed into the investigation of his detective, Lew Archer, including the runaway father, the canyon forest fire, and California’s unique culture, accurately presented in a book that ranges the state from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

We see the compassion for which Archer is justifiably known, but there is also ample evidence of his intelligence as his creator has him quote Dante in a conversation so well written that it fits in seamlessly.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988 (very slightly revised).

Covers:

Shown above is the cover of the 12th printing that Marv was referring to. Others covers that have graced this book are shown below, but to my mind, none of them surpasses the Knopf hardcover First Edition:

Here’s the hardcover UK first edition, from Collins Crime Club, 1963:

And I believe this to be the first UK paperback edition, published by Fontana in 1965:

To finish up this short display, a paperback edition from France, Éditions J’ai Lu #1662, 1984.

[UPDATE] 06-22-09. Submitted by Juri Nummelin, a hardcover edition published in Finland:

See the comments for a link to a short write-up about Juri about Macdonald, including this book.

Mon 10 Nov 2008

ROSS MACDONALD – The Drowning Pool.

Bantam, paperback reprint; movie tie-in edition, 1970s. Hardcover first edition: Alfred A. Knopf, 1950. Many reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

I wasn’t thinking very much about it, so when I picked this book up and started to read, I found myself caught up in a small time warp, which caught me by surprise, but it was one of my own making.

I’ll explain.

On both covers, front and back, there are a dozen or more color shots taken from the movie, released in 1975. Lots of photos of Paul Newman, in other words, in all kinds of situations, plus a handful more with Joanne Woodward in them — all rather tiny, but the immediate effect was to put me in a mellow 70s sort of mood, when both Paul and Joanne were much younger, and so was I.

So when I hit page 9, where Lew Archer stops at one of those old-fashioned motor courts that consists of small cottages that the owner walks you down to and lets you inspect the accommodations before you register, it was jarring, and it immediately sent me back to the copyright page only to discover that — whoa! — the book came out in 1950.

It wasn’t a 1970s book, at all. (And it took only a little more effort to look up the fact that The Drowning Pool was only the second novel that Archer appeared in; the first was The Moving Target, from 1949. Where does the time go?)

We don’t learn a whole lot about Archer’s background in this book. Previously married and now separated, or perhaps more likely, divorced, that’s about all we learn about him — except for his strong standards of right and wrong. Beware to the client who hires him and changes her mind. Once hired to do a job — in this case, to discover who sent a woman with an already shaky marriage a letter that threatens to tell all — he’s in it to the end.

Beginning with a marriage on the rocks, Archer’s slow but methodical investigation expands to include a daughter who at 15 is too young to attract the such serious intentions from the family chauffeur; her grandmother, the matriarch of the family; a police chief who is obviously smitten with Archer’s client; a weak-kneed husband who never had to work a day in his life; and oil — which means money, trouble, and murder.

It’s a complex case, laid out by Macdonald in simple fashion. It would have been easy to make a tangled mess of the various threads of the plot darting here and there — Archer is on the road a lot, and in serious trouble more than once — but the telling is clean, straight-forward, and filled with enough picturesque similes and metaphors to fill a book.

Here are just a few — I can’t resist:

Page 77: “For an instant I was the man in the [distorted] mirror, the shadow-figure without a life of his own who peered with one large eye and one small eye through dirty glass at the dirty lives of people in a very dirty world.”

Page 79: [talking to a very young prostitute] “Her breasts were pointed like a dilemma. I pushed on past.”

Page 82: “[Graham] Court was a row of decaying shacks bent around a strip of withering grass. A worn gravel drive brought the world to their broken-down doorsteps, if the world was interested. A few of the shacks leaked light through chinks in their warped frame sides. [The office] looked abandoned, as if the proprietor had given up for good.”

Right now I don’t remember much of the movie, whether it followed the book very well or not, but either way, I think I’ll always have Paul Newman in mind when I read any of the Archer books. This one is a good one, and while all the clues point one way, except for one or two puzzling gaps, which — as it turns out — are nothing to be concerned about. Macdonald knew what he was doing, and any loose ends are firmly nailed down, solidly, to perfection, and with no seams showing.

— August 2002 (slightly revised)

Thu 9 Feb 2023

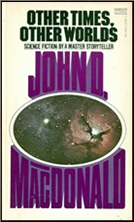

JOHN D. MacDONALD “Ring Around the Redhead.†First published in Startling Stories, November 1948. First reprinted in Science-Fiction Adventures in Dimension, edited by Groff Conklin (Vanguard Press, hardcover, 1953). First collected in Other Times, Other Worlds (Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback original, October 1978).

I don’t imagine that any young SF reader coming across this story in the (at the time) most recent issue of Startling Stories had any idea that the author would become rich and famous a few years later as the John D. MacDonald you and I know today as, for example, the author of the series of mystery novels for which he is most remembered, thous about “salvage expert†Travis McGee.

Nor did, I suppose, those fans of the Travis McGee books happen to know that he started out writing SF stories — as well as mysteries — for the pulp magazines of the late 1940s. I don’t know if all of his early SF work were later collected in Other Times, Other Worlds (1978), but there are sixteen of them, and ones MacDonald much have felt worth reprinting at the time.

“Ring Around the Redhead†is, well, one of them, and it begins with a defendant in court having been accused of murdering his next door neighbor, and in a most vicious fashion: the dead man had been decapitated as if by a mammoth pair of tin snips. When the defendant, an amateur tinkerer, gets to tell his story to the jury, it really is quite a story. Having strangely discovered a mysterious ring in his workshop in the basement, he learns by trial and error that by reaching through it, he can bring back, among other items, valuable jewels, for example. (This is why he is seen arguing with the neighbor, who has discovered this.)

One day, then, he brings a beautiful girl back through the ring, a redhead, who is wearing next to nothing but strangely still something.

Hence the title of the story, which has no other objective than to be fun and amusing. No deep scientific principles are discussed in this tale. What this tale reminded me of, more than anything else, are the SF stories very common back in the early 30s, based on speculation but not a whole lot of down-to-earth physics – but, in this case, a tale that’s a whole lot better written.

Nonetheless, without a solid background in science, JDM must have decided that science fiction was not a field where he had much of a future. Considering how things worked out for him, this was a wise choice.

Fri 5 Apr 2019

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

MENACE. Paramount, 1934. Gladys Michael, Paul Cavanaugh, Berton Churchill, Henrietta Crossman, John Lodge, Raymond Milland, Halliwell Hobbes, Robert Allen, Forester Harvey, Arletta Duncan Screenplay Chandler Sprague, Anthony Veilliers based on the novel R.I.P by Philip MacDonald (Collins, UK, 1933; published in the US as Menace, Doubleday, 1933). Directed by Ralph Murphy.

RYNOX. Ideal, 1932. Stuart Rome, John Londgren, Dorothy Boyd. Screenplay (mostly uncredited) J. Jefferson Farejohn, John Jerome, Philip MacDonald (his novel, Collins, UK, 1930; published in the US as The Rynox Murder Mystery , Doubleday, 1931), and Michael Powell, the latter also director.

These two adaptations of novels by Philip MacDonald were virtually unknown to me until they showed up on YouTube, and certainly neither of them is in a class with his better known film adaptations such as X Vs Rex, Patrol, The List of Adrian Messenger (which ironically has a screenplay by Anthony Veilliers who co-wrote this one), 23 Paces to Baker Street, or even the earlier version of that book under its British title The Nursemaid Who Disappeared.

Menace is the somewhat better of the two, working at least as a suspense film to some extent if not as much as a mystery, and moving with some vigor. Gladys Michael, Paul Cavanaugh, and Berton Churchill are wealthy friends in Africa just before the monsoons. Bored, they convince dam supervisor Ray (billed as Raymond) Milland to leave his post to play bridge with them. When the storms break early, Milland tries to fly back through the storm only to arrive in time to see the dam collapse and his mother and sister below killed, as well as hundreds of others.

In a fit of remorse he flies his plane into the ground taking his own life.

Back in England his brother Timothy, who is mentally disturbed, swears vengeance on the three he blames for his brother’s death, is put in a mental asylum, escapes, and one year later they are in Malibu in Michael’s beach side villa when he finally catches up with them.

Soon to be trapped in the villa with them are a new butler (Halliwell Hobbes) hired from an agency, and who proves to be a crack shot when Cavanaugh tests him; Michael’s younger sister, who she raised when their parents died and her fiance (Arletta Duncan and Robert Allen); Cavanaugh’s driver (Forester Harvey); and a nosy eccentric old lady neighbor (Henrietta Crossman) who shows up on their doorstep with her son’s friend in tow (John Lodge).

Not long after the lights go out, and the phone goes dead and all the autos are sabotaged. Not long after that Churchill is killed by a knife thrown by Timothy. Then Cavanaugh barely survives an attack.

Now they are waiting for Timothy to strike and unsure who he is, if he is one of them at all. All we know is we have seen the butler attack Michael’s sister and tie her up and gag her.

Not much real mystery here about who the killer is, even with a bit of misdirection, and there is one decent clue planted early on that does explain one surprise; plus two suspects complain of headaches– which we know Timothy suffers from — as half decent red herrings.

What is notable here is not the film itself, which is at best a minor success, but just how stiff and unreal everyone else in the film seems after Ray Milland’s few scenes at the start. His perfect ease on screen, even delivering what isn’t much more than ‘tennis anyone’ dialogue, compared to everyone else in the film is striking. The film actually never recovers from his early death because there is no one in the film even remotely as attractive or natural on screen.

It is about as clear a demonstration of the power of a natural screen presence as you will ever see. It’s as if everyone else is in a different film.

Rynox, based on the The Rynox Mystery, basically has one thing going for it. It happens to be one of the earliest films directed by Michael Powell, who as one half of the Archers (with Emric Pressberger) would create such films as 49th Parallel, Black Narcissus, A Matter of Life and Death, I Know Where I’m Going, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and more.

Tycoon and founder of Rynox, F. X, Benedik (Rome) is threatened by the theatrical and larger than life Boswell Marsh. When Benedik is murdered, son Tony Benedik (Longdren, and the closest thing to Anthony Gethryn in the film — ironically Longdren is also television’s first Sherlock Holmes) takes over the business and the investigation.

Unfortunately the very nature of film means the big reveal that made the novel a success is so obvious even the most naive film goer must have found it crystal clear. The script tries hard — little surprise with that lineup — and Powell shows a few directorial flourishes, but when the chief surprise in any mystery is telegraphed as this one is by bad acting and worse makeup, there isn’t much anyone can do to save it.

This might have worked better is they had actually filmed the book as a detective story instead of trying to getting into character and showing the viewer far too much. I’ll only say that something similar worked much better when John Huston tried his hand at a MacDonald novel.

Both films are mostly of interest to MacDonald fans or film historians, the former for an early star turn by Ray Milland and the latter as a footnote in the career of Michael Powell. I won’t warn anyone off them, because both have their moments, but take them for what they are, primitive variations on more familiar formulas.

Menace at least has the advantage of moving fast and one or two touches of suspense and actual mystery, Rynox — well, it’s an early film by a great director.

Wed 3 Aug 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

PHILIP MACDONALD – The Polferry Riddle. First published as The Choice (Collins, UK, hardcover, 1931). Reprinted as The Polferry Mystery (Collins, UK, hardcover, 1932). Reprinted under this title by Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1931. Also: Vintage Books, US, paperback, September 1983.

This one starts out as an ace number one detective puzzler, complete with a dark and stormy night, two visitors to the mansion rescued from the river, then sudden death, with the young wife of the home’s owner found with her throat slashed some time during the night in her bedroom. No weapon can be found.

The three men give each other solid alibis. Each of four others asleep upstairs could have done it, but none of them have a motive. The house was locked tight. An outsider could not have done it. Even Colonel Anthony Gethryn is stumped. With no leads and no evidence the case is put on hold until two of the four members of the household meet with fatal accidents — or are they?

A good chunk of the middle of the story basically becomes a thriller, as Gethryn and his friends from Scotland Yard make a frenzied chase halfway across England to avert the murder of a young woman who was also one of the four.

What each of the “accidents” also does is narrow down the list of possible suspects to the original killing, one at a time, and still the police are stumped. No one could have done it, and with no weapon in the room, it could not have been suicide.

But with Anthony Gethryn on the case, not all is lost, of course. I think the ending is a cheat, though, and I say this reluctantly, since until then, this was a highly readable example of the Golden Age of detective fiction. When it comes down to it, though, I don’t think Gethryn’s logic holds up, nor was I happy when the vital clue was found at nearly the very last moment. Why the police didn’t find it in their original investigation, when they claimed they scoured the house from top to bottom, I have no idea. Put this one solidly in the “Disappointing” category.