Search Results for 'The Big Sleep'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 12 May 2013

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

SAM S. TAYLOR – Sleep No More. E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1949. Signet #821, reprint paperback, October 1950.

In Blood in Their Ink, Sutherland Scott gave high marks to this novel. Oh, sure, Scott himself wasn’t much of a writer, to give him praise beyond his due, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t have good taste. Gee, if we went by the theory that it takes one to know one, readers struggling through one of my reviews might question my judgments.

To make a short story long, Scott put me on to a good thing here. While it breaks no new ground, it does employ the best from the hard-boiled genre. Though not invariably excellent, the obligatory metaphors and similes are at least very good.

Recently released from the Army, Neal Cotten has established his very own detective agency in Los Angeles, where it would seem from the literature there must have been a P.I. office in every block. Business is slow until Cotten gets a client who, suspecting blackmail, wants her daughter’s spending habits investigated.

Before Cotten can turn up much information, the client’s daughter commits suicide, or so the official theory has it. With his ’35 Buick no longer fit for speed or hills, Cotten, who is in somewhat better shape, starts on the trail.

An interesting character in Cotten and an engrossing picture of early postwar Los Angeles make me forgive the appearance of a silenced revolver.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 1991.

The Neal Cotten series —

Sleep No More. Dutton, 1949.

No Head for Her Pillow. Dutton, 1952.

So Cold, My Bed. Dutton, 1953.

For much more about both Sam S. Taylor and his PI character, Neal Cotten, check out “The Compleat Sam S. Taylor,” posted on this blog back in 2007.

Wed 28 Jul 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

WHILE THE CITY SLEEPS. MGM, 1928. Lon Chaney, Anita Page, Carroll Nye, Wheeler Oakman, Mae Busch, Polly Moran. Director: Jack Conway. Shown at Cinecon 27, Hollywood CA, September 1993.

Even with a missing reel, this Lon Chaney film was a stunning thriller. Chaney plays a tough New York detective on the trail of “Mile Away” Skeeter (who’s always a mile away from the crime when it happens).

Chaney’s hard as nails, but he’s got a soft spot for Myrtle (played by Anita Page, a Cinecon guest) and for a lad who’s got in with mob and just needs the right influence to go straight. But then the lad falls for Myrtle, who’s mighty taken with him and…

Chaney’s rough-hewn face is a perfect mask for the hard-nosed cop, but bruised the way his heart will be. Nobody could ring the changes on pathos like Chaney, probably the greatest of silent screen dramatic actors. A smashing performance and superb photography and direction.

Mon 7 Jun 2010

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

L. R. WRIGHT – Sleep While I Sing. Penguin, US, paperback reprint, October 1987. Bantam Seal, Canada, pb, 1998. Hardcover edition: Viking, US, 1986.

Genre: Traditional mystery/police procedural. Leading character: Staff Sgt. Karl Alberg, 2nd in series. Setting: Victoria, B.C., Canada.

First Sentence: The clearing lay fifty feet from the two-lane Sunshine Coast Highway.

Staff Sergeant Karl Alberg, who never wears his uniform, is looking for the killer of an unknown woman whose throat was slit before her body was propped against a tree and her face washed.

Alberg’s top suspect is a visiting actor, but there is a complication; he is currently dating the town’s librarian, Casandra Mitchell, to whom Alberg is attracted. But is the case on the right track?

I read the first book in this series several years ago and don’t know why I’ve not been back as I really like Wright’s writing. She creates a wonderful sense of place with such evocative descriptions… “It [the rain] fell heavily, but meant no harm.”

I so appreciate which an author’s voice causes you to stop and imagine. The characters are very interesting and very well drawn. Alberg is assured professionally, but much less so personally.

The female characters are confident yet bemused by their reactions to the actor who is Ahlberg’s primary suspect. You get a real feel for each of the characters and with some very effective red herrings, it’s not easy to identify the killer.

The plot is well constructed. The suspense and feeling of menace are created with subtlety but are very much in evidence. Subtle is the perfect word for Wright’s style.

The plot unfolds piece-by-piece in a way that makes sense. This is a very good traditional mystery. It won’t be nearly so long until I read the next book in this series.

Rating: Very Good.

The Karl Alberg series —

1. The Suspect (1985)

2. Sleep While I Sing (1986)

3. A Chill Rain in January (1990)

4. Fall from Grace (1991)

5. Prized Possessions (1993)

6. A Touch of Panic (1994)

7. Mother Love (1995)

8. Strangers Among Us (1995)

9. Acts of Murder (1997)

Wed 19 May 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

RAYBURN CROWLEY – The Valley of Creeping Men. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1930. Hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap, no date.

This is a book that any lover of high adventure, goofy science, and lost-race novels won’t be able to put down.

Somewhere in Africa, protected from the outside world by a forbidding mountain lies a valley in which — legend has it — dwells a race of golden gorillas, somewhere on the evolutionary scale between ape and man:

“I’ve heard it is not an ordinary gorilla, but yellow like a collie; that it’s very close to human, sometimes has a vile temper, and sometimes is disgustingly affectionate.”

The murder in London of the brilliant but loony scientist Marakoff — the discoverer of the gorilla — sets off an international pursuit that includes more murders, treachery and relentless peril.

There’s some colorful writing here, the kind that always sets my pulse to pounding:

“At a point near the West Coast of Africa there lies a valley; no white man has ever gone into it. The natives have a great dread of it,. It lies far up a sluggish tropical river-the Sanaga. The river is impassible to big canoes except after the rains. The mountains of the Kameroons hem it in on both sides. The entrance to it lies through a narrow defile. Even this is cut off by a giant cataract. What lies behind that wall of water no one knows, except — perhaps — Marakoff.”

And away we go. The women are seductively beautiful, the men strong and intense, and the landscapes are painted with a skill that’s a cut above some of the plotting:

“The smokey haze of London had already clouded the short November afternoon to dusk. As he contrasted the London greyness with the rich tropical world that awaited him, he felt alien and estranged. In Africa, now, the sun would be blazing on fantastically brilliant colors. Or when the quick night had come, there would be the moon, yellow and ripe, hanging like a melon in the liana-hung tangle of the forest. Africa was in his senses, in his heart.”

Edgar Rice Burroughs, eat your heart out!

In an appendix at the end of Chattering Gods, the sequel to Valley, published by Harper in 1931, the publisher poses the question “Who IS Rayburn Crawley?”

In an accompanying letter, Crawley defends his anonymity by claiming that: “Any author worth reading can be known, and very fully known, by his books.”

The publisher calls this a challenge and, listing several questions that might be asked about the reclusive author, offers autographed copies of the two books to “the persons who answer these questions correctly.”

Laura Spencer Portor Hope and Dorothy Giles are identified in the current version of Hubin as the authors hiding behind the Crawley pseudonym, and Victor Berch has added that their identity was known as early as July 7, 1958, when the copyright on the book was renewed.

Now if only somebody could find out the names of the winners of the Harper contest. It’s intriguing, to say the least, that autographed copies, in dust jacket, of the two books may be in some collector’s private library.

Editorial Comments: Walter sent me this review after he spotted this book in Victor Berch’s “Checklist of Harper’s Sealed Mysteries,” announced on this blog not too long ago. This is a revised version of a review he wrote some 20 odd years ago, and he admits that he’s been wondering about the author’s identity ever since.

As good as Walter says this book is, why it should have been published as a Sealed Mystery, along with the John Dickson Carr’s, Hulbert Footner’s and others is another mystery that’s lost in the mists of time.

Mon 19 Oct 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

DICK LOCHTE – Sleeping Dog. Arbor House, hardcover, 1985. Paperback reprints: Warner, 1986; Poisoned Pen Press, trade pb, 2001.

Dick Lochte’s Sleeping Dog, recently reprinted by Warner, features Serendipity Dahlquist and Leo G. Bloodworth, “a spunky little miss and case-hardened private shamus.”

Serendipity is only fourteen, a 1980’s version of Holden Caulfield. When she and Leo find a corpse, she is blase, not queasy, saying, “I’ve seen dead people before, tons of ’em. On TV.”

This unlikely team works together in a wild, fast-moving mystery about such unlikely subjects as dog-fighting and television. The Southern California scene, used so often in the past, has seldom been better portrayed, with an especially devastating picture of the ocean town, Playa del Rey.

Equally good is Lochte’s picture of Bloodworth’s car: “It had dark tinted windows, the better to hide behind. Its back seat was covered with jackets, sweaters, strange hats, brown paper bags, squashed into balls, Big Mac wrappers, greasy fried chicken boxes, and empty beer cans. It was the car of a dedicated, working gumshoe.”

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 3, May/June 1987.

[UPDATE] 10-19-09. Sleeping Dog won the Nero Wolfe Award and was nominated for an Edgar, Shamus, and Anthony Award when it came out in 1985. The only other novel-length appearance of this delightfully mismatched pair of detectives was Laughing Dog (Arbor House, 1988).

Thu 10 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

RUTH RENDELL – A Sleeping Life. Doubleday, hardcover, 1978. UK hardcover: Hutchinson, 1978. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and soft.

Chief Inspector Wexford’s approach to a murder is often based on intuition as well as fact, but this time around, working on the death of a middle-aged woman with no trace of background, he seems to run into stone walls no matter which way he heads.

Adding to his frustration is a domestic crisis at home as well, provoked by his daughter’s evangelical conversion to Women’s Lib.

Rendell obviously intends for the ending to come as quite a surprise, but unfortunately the secret’s too big to keep very well. The observant reader will eventually find that all the clues are pointing in one direction only.

Even so, the workmanship of this well-constructed mystery is exactly readers have come to expect from one of the best authors writing in the field today. There’s no way anyone’s going to be disappointed with this one.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979

(revised).

[UPDATE] 09-10-09. In spite of the good review I gave this book, it’s been a long time since I read anything by Ruth Rendell. I always enjoyed her Wexford books, but her standalones, mostly psychological crime novels, not so much.

Wed 10 Jun 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

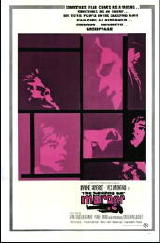

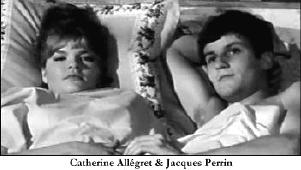

THE SLEEPING CAR MURDER. Seven Arts, 1961. Simone Signoret, Yves Montand, Pierre Mondy, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Jacques Perrin, Michel Piccoli, Catherine Allégret (debut), Charles Denner. Based on the novel Compartiment Tueurs (aka The 10:30 From Marseille) by Sébastien Japrisot. Director: Costa-Gravas.

Before he made his mark as a political director with leftist leanings, Costa-Gravas made his debut with this slick little police thriller about the hunt for a mad killer.

The police are represented by Inspector Grazziano (Grazzi) played by Yves Montand and his younger partner Grabert played by Jean-Louis Trintignant, whose involvement begins with the discovery of a body on the Phoce’en, the 10:30 morning train from Marseille, and an attractive young woman who has been murdered.

We are almost instantly in Maigret country, but to Costa-Gravas’s credit, he establishes his own visual style and technique rather than rely on memories of films of Simenon’s novels. There is nothing leisurely or casual about Montand and Grabert. They are real policemen who chew on antacids, smoke too many cigarettes, and take endless notes, and almost from the top they are up to their necks in it, because before they have finished sorting the first corpse there’s a second waiting for them. The weariness in Montand’s lined doggedly handsome features becomes a character in itself.

Police and authorities are seldom sympathetic characters in Costra-Gravas’s films, so it comes as a shock how much this film identifies with its put-upon policeman heroes.

They are decent men with lives outside the office, and would rather do just about anything than have their superiors down their necks as they face an increasing number of corpses and a possibly mad killer.

Costa-Gravas relies less on flashy camerawork and more on storytelling in this one, with atmosphere to spare, thanks to cinematographer Jean Tournier’s brilliant camera work, the film’s quick pace and the well-done action scenes.

Signoret and the rest of the cast are fine, as might be expected, and thanks to staying close to Japrisot’s tight cinematic script, the film is both suspenseful and a good mystery well-solved.

That said, you would do well to find a copy of the film with subtitles and avoid the awful dubbed version I first saw.

Costa-Gravas became a world wide sensation with his next film, Z, but his increasingly leftist films became more propaganda than entertainment, though his one American film Missing, with Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek, was highly thought of. Since then politics outstripped the film-making in too many of his later works. Montand also appeared in Z, State of Siege, and The Confession all helmed by Costa-Gravas, forming one of the French cinema’s most productive teamings.

Sébastien Japrisot is one of the more familiar French writers on this side of the Atlantic, thanks to the films of his works, including his original screenplays for Rider on the Rain and Goodbye Friend, and adaptations of many others like Lady in the Car With Glasses and a Gun and One Deadly Summer. Most recently the 2004 film of his novel A Very Long Engagement was an international hit.

Sun 12 Mar 2023

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

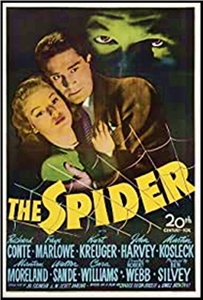

THE SPIDER. 20th Century-Fox, 1945 Richard Conte, Faye Marlowe, Martin Kosleck, Kurt Kreuger, Mantan Moreland, John Harvey, Ann Savage . Screenplay by Jo Eisenger & Scott Darling based on the play by Fulton Oursler (Anthony Abbott) and W. Scott Darling. Directed by Robert Webb.

Well done if minor film noir from fairly early in the game, opening with an overhead panning shot in the streets of New Orleans where Lila Neilson (Faye Marlowe) walks toward a dark staircase with a white painted sign that reads “Cain and Conlon – Private Investigators” as she tells us that Cain (Ann Savage), the distaff side of Cain and Conlon, has approached her to tell her that her partner Chris Conlon (Richard Conte) has information about the death of Lila’s sister.

Conlon’s manservant, Mantan Moreland, directs her to a cafe where Conlon is holding forth with his reporter friends on a dull night. Conlon is an ex-cop, a bit too slick for the taste of his ex-cop buddies and about to run afoul of that reputation for running close to the edge.

There is a nice touch in the scene where Moreland confronts Lila in the dark hallway outside Cain and Conlon’s office door and when he walks away w,e notice a shadowy figure with a hat pulled low step out of the deeper shadows.

For a fairly short B-film, the plot is fairly complex, involving a phony psychic called the Spider Woman whose scam was involved in Lila’s sisters death and Ernest, The Great Garrone (Kurt Krueger) her partner and his top man Martin Kosleck, and something Cain has uncovered in documents she is trying to get to Conlon.

When Cain meets Conlon at his apartment she is killed there, and Conlon, knowing the police will tie him up with red tape accusing him, transports her body to her own apartment to be found.

Of course when the police discover tha,t he is on the run.

In fairness, however stupid that seems, it is standard private eye behavior in print and on screen.

The playlike structure shows, and of course there is a bit of the usual shtick with Moreland as comedy relief (which for once isn’t the best thing in the film), but on the whole this is a decent film noir outing that benefits from the attractive cast and particularly Conte as a slick private detective right out of the pulps.

Conte would later play Sam Spade in a television adaptation of a Hammett story and while Conlon is no Spade, he is still well within the slick but not as bright as he thinks he is tradition of movie eyes.

If there is a problem, it’s the casting alone is enough to give away who the culprit is, but considering the quiet menace the film manages to create that is a minor complaint. The details getting to the reveal at the end are done well and involving enough you probably won’t mind.

The private eye tropes had been around on the rough edges of movies since the early Thirties and films like Private Detective 62 and Mister Dynamite (suggested by stories by Raoul Walsh and Dashiell Hammett respectively), not to mention the Ricardo Cortez Maltese Falcon adaptation, though it is later in the Thirties before the more modern take starts to take form (in Private Detective 62 William Powell is a disgraced diplomatic agent who uses his skills to prey on women cheating on their husbands more than investigates crimes), helped along by the Thin Man films and cemented by John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon and the Lloyd Nolan Michael Shayne films. Murder My Sweet and The Big Sleep nailed the final screen image of the private eye for good in terms of the film version of the trope.

The evolution of the private detective in film from the dumb fat guy with cigar and bowler hat to the slicker version we are familiar with is fairly interesting with some unusual side streets like Nigel Bruce’s Cockney private detective in Murder in the Caribbean. The earliest incarnations were fairly unscrupulous pseudo crooks usually played by the likes of William Powell, Edmond Lowe, or Ricardo Cortez evolving through the Thirties into more acceptable social types like Preston Foster’s Bill Crane, Powell’s Nick Charles, Bogart’s Spade, and Nolan’s Shayne all the way down to Dick Powell and Bogie’s Philip Marlowe. Conte’s Chris Conlon is very much in that transition stage.

I don’t want to oversell this. It is low budget, cliched (but good cliche). It does the tropes well, the cast is good, and the main disappointment is we don’t get more of Ann Savage’s Flo Cain as a smart female private eye. There was a good concept there that got thrown away in favor of a fairly standard story, however hard I try to review the movie they made and not the one they should have made.

Film Noir was still in its formative stages at this point and this one captures some of the feel and look surprisingly well for its budget, with several actors who will play a role in the genre as it develops. I don’t know if it is on DVD, but you can find it on YouTube or Internet Archive in a decent print in several formats to watch or download in Community Videos. This one is definitely in Public Domain so there is little worry it violates anyone’s rights.

Fri 27 May 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

THE VALUE OF MIDDLE OF THE ROAD DETECTIVE NOVELS

or WILLIAM ARD’s The Diary and JONATHAN LATIMER’S Murder in the Madhouse, by TONY BAER.

There was some review on the back of a Maigret book that said something about how many countless traveling businessmen had been comforted, salved, and assuaged in their lonely motel rooms by these books.

So I guess that’s where I’m going with this.

Murder in the Madhouse is the first of the Bill Crane detective novels. He’s been assigned to investigate a theft of a strongbox of one of the inmates. He enters incognito, ‘disguised’ as a crazy drunkard who thinks he’s a great detective.

Once he arrives, a series of murders ensue, for which he serves as a chief suspect of the local stupid sheriff.

Crane’s detection is surprisingly effective, and justice, after drinks, is served.

The Diary (Timothy Dane #3), is pretty much a straight ripoff of The Big Sleep. Dane gets called in by a millionaire widower because he is being blackmailed over his sexpot 18 year old daughter’s stolen diary. Murders ensue, for which Dane serves as chief suspect of the stupid DA. Dane’s detection is surprisingly suspect, and justice, hold the drinks, is served.

Both the books are well told. The authors are natural born writers, who write smoothly, entreatingly, and know how to tie a thing together.

You finish the book, and it’s done. You won’t remember it.

On the other hand, in the time that you’re in it, you’re in it. It holds you.

And all of the terrible shit of the world, and of the day, it disappears.

And the smartass detective, buzzing off highballs, poor, honest, and self sufficient, keeps punching onward against a screwed up world.

Thank you, Mr. Hardboiled Detective, for showing us the way.

“I can’t go on. I’ll go on.” — Beckett

Thu 2 Dec 2021

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

In 1946, soon after the end of World War II, the editors of the high-paying Esquire decided to launch a series of short detective stories and invited several authors to create a new character for possible publication in the magazine. Among those solicited was that incomparable filbert Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), who strung together an outrageous plot about a barking clock and an astigmatic witness and dreamed up a 7½-foot-tall mathematically-educated hick from the sticks as his new detective.

Reasonably enough, Esquire rejected the story. Who won the prize that Keeler lost? A guy who happened to have the same first and last initials as our Harry. The subject of this column.

***

About the life of Henry Kane very little has surfaced. He was born in New York City on 18 May 1908 as Henry Cohen and apparently graduated from one of the city’s several law schools in the 1930s. How long he practiced law is unknown, but it does seem clear that he preferred writing to legal work.

Whether he served in World War II is also unknown. At the time of Esquire’s hunt for a new series character he seems to have published nothing, and what the editors saw in him is likewise a mystery. The character he created for the magazine was Peter Chambers, a tough but sophisticated Manhattan private richard (as he prefers to call himself) whose first appearance in short-story form was “A Glass of Milk†(Esquire, February 1947).

It was also early in 1947 that Chambers debuted as protagonist of a hardcover novel. Whether the early short stories preceded or followed A HALO FOR NOBODY (Simon & Schuster, 1947) is anyone’s guess: my own is that at least the first couple of them came first. Kane stayed with S&S for a few years, then migrated to the field of paperback originals where he flourished during the Fifties and Sixties, having Chambers narrate his own cases in a wackadoodle style which his admirers have dubbed High Kanese.

It’s likely that Chambers was the uncredited inspiration for the hit TV series PETER GUNN (NBC, 1958-61), for which the tie-in novel (PETER GUNN, Dell pb #B155, 1960) was written by, you guessed it, Henry Kane. Later in the swinging Sixties Kane reconfigured his character as protagonist in a series of X-rated paperbacks for Lancer (1969-72).

During the final phase of his career he turned out a number of stand-alone hardcover thrillers, some under his own byline, others as by Anthony McCall, Kenneth R. McKay, Mario J. Sagola (a name probably meant to evoke the Godfather saga) and Katherine Stapleton. He died in his home at Lido Beach, Long Island on 10 October 1988.

***

A HALO FOR NOBODY opens with a report by Chambers to his friendly enemy NYPD Lieutenant Louis Parker, and of course to us: he was walking down Park Avenue in the lower Eighties on the way to an appointment with a potential client when, a block or so ahead of him, he witnessed an attempted kidnapping and the murder of a woman, who turns out to be the potential client’s wife.

Being armed at the time — which establishes, I suppose, his machismo — he fired several shots into the back of the taxi in which the criminals were escaping. The taxi is later found in Central Park with two dead men in it: the driver and a known hoodlum.

Soon afterwards, Chambers is hired by the dead woman’s husband not to solve the murder of his wife, whom he hated, but to find out why someone is trying to blackmail him when he knows he’s done nothing blackmail-worthy. It would take several pages of summary to penetrate deeper into Kane’s Chandleresque plot labyrinth and I doubt it would benefit anyone to read them.

When A HALO FOR NOBODY was published in 1947, Kane was touted by Simon & Schuster as “a worthy successor to Dashiell Hammett.†Talk about ridiculous! The main connection between the two is that Kane, like so many others, borrowed from Hammett the climax of THE MALTESE FALCON.

To Raymond Chandler he owed a bit more, including some elements of his protagonist — even the names have the same cadence, Philip Marlowe and Peter Chambers — and the all-but-incomprehensible labyrinthine plot, although he does keep to a reasonable minimum the vivid figures of speech in which Chandler indulged perhaps too often.

The stylistic feature of HALO that jumps out at the reader is Kane’s habit of converting several short sentences into a single long one by the repeated use of the most common conjunction in the language. Here’s an example from a nightclub scene.

Blue smoke curled and wavered and curtained the ceiling and the girl rocked at the microphone and her eyes were closed and her dark eyelids glistened and she sang slowly in a deep, hushed voice, throbbingly, against the wash of subdued conversation.

I have a vague recollection that this trope started with Hemingway but I doubt that Papa used it to anywhere near the same extent as Kane.

Anyone writing a dissertation on political incorrectness in PI fiction will go no farther than Chapter Four when Chambers encounters a gay ex-gangster and calls him, to his face, “a fairy, a phony, a queerie, a pervert.†Any such reader will miss perhaps the most memorable scene in HALO, the gunpoint tête-à -tête between Chambers and the most cold-blooded of the novel’s three murderers, who is also perhaps the most philosophical killer in the entire Kane Kanon:

“Chambers, a long time ago I learned it was dog eat dog. A human life means nothing; your own life, conversely, means everything. We are taught differently. Comes a war — how quickly they attempt to reteach us. You have no personal grievance against the soldier of the enemy — -but you kill him, unfeelingly. A human life, in the vast perspective, means nothing; but protect yourself. With yourself, there is no perspective.â€

At the end of the scene a slightly wounded Chambers faints, vomits several times, finds a bottle and guzzles nonstop for five minutes. He then segues into the MALTESE FALCON climax from which, unlike Sam Spade, he emerges with five bullets in his stomach. From his hospital bed he identifies the third and final of the book’s murderers. That too, I suppose, is machismo.

In his review for the San Francisco Chronicle (16 February 1947) Anthony Boucher wisely made no attempt to summarize the plot of HALO but limited himself to describing Chambers as “a private eye who thrives on drink, wenching and coincidences†and the book itself as a “[r]easonably good toughie, at once more literate and more confusing than most….†I cannot better that description.

***

The second Chambers novel, ARMCHAIR IN HELL (1948), is similar to HALO in opening with three corpses. It’s after midnight when our private richard is ungently pulled out of an alcoholic haze by one of his most lucrative clients, a wealthy gambler known as Ziggy who’s found a naked woman with her throat slit in his house on West 76th Street.

At the house Chambers and Ziggy find two additional corpses: a henchman of the gambler’s and a prominent art dealer. Chambers has his client steal a car, take the bodies and dump them near the river, then joins Ziggy for a 4:00 A.M. conference over cheesecake and coffee and learns that the gambler had been promised $500,000 to act as go-between in the transfer of some priceless tapestries that had been taken out of France by the Nazis during World War II.

Those tapestries are Kane’s version of what Hammett called the black bird and Hitchcock the McGuffin. Like any McGuffin worthy of the name, this one is being sought by an assortment of questionable characters, including a blonde sexpot, a brunette sexpot, an art critic (whom Chambers describes as “a California elfâ€), an oddball Frenchman, a pool shark, a ballroom manager, and a sinister dwarf with a huge moronic goon who, in a scene reminiscent of the beating of Ned Beaumont in Hammett’s THE GLASS KEY, marks Chambers up with a set of brass knuckles.

The climax calls to mind the conference among all the parties near the end of THE MALTESE FALCON, with Chambers pulling the strings so that the murderer is gunned down in front of witnesses by one of the other contenders for the tapestries.

Our friend the student of political incorrectness will find short rations in this one, mainly the scene where Chambers asks about another character’s sexual preference or, as he phrases it, whether the man is “a nancy…. A fruit, a milky way, a buttercup.†Any such student who stopped there would miss perhaps the most interesting moment in the book, a sort of meta-scene where Chambers describes not only himself but almost every PI who came into the genre in Chandler’s shadow.

He “has no wife, or sleep, or food, or rest. He drinks, drinks more, and more; flirts with women, blondes mostly, who talk hard but act soft, then he drinks more, then, somewhere in the middle, he gets dreadfully beaten about, then he drinks more, then he says a few dirty words, then he stumbles around, punch-drunk-like, but he is very smart and adds up a lot of two’s and two’s, and then the case gets solved….â€

***

Later that year Simon & Schuster published REPORT FOR A CORPSE (1948), a collection of Kane’s first six short stories, all from Esquire. Whereas in his book-length cases Chambers had been a member of a PI firm complete with senior partner, an old-maidish secretary and at least three legpersons, in these shorter tales he’s a lone wolf with only the secretary Miranda Foxworth carried over from the novels.

For some unaccountable reason the stories in book form are not printed in chronological sequence but I shall cover them in Esquire’s order.

“A Glass of Milk†(February 1947) opens on a Sunday afternoon as Chambers enters an elegant Madison Avenue drinking place, spies a beautiful blonde at the end of the bar nursing a glass of milk and orders another: obviously a prearranged signal. The blonde leaves and Chambers follows her to her apartment where she makes him a real drink, tells him she’s changed her mind about hiring him, and gives him fifty dollars for his time and trouble.

That evening he’s visited by his friendly enemy Lieutenant Parker, telling him that the woman has been found dead, with her face mashed in, and Chambers’ prints all over the hotel suite. Chambers explains about the assignation at the bar but the apartment staff insist she never went anywhere that day and the bartender says he never served any blonde a glass of milk.

Instantly we’re reminded of the situation in Cornell Woolrich’s iconic novel PHANTOM LADY (1942), with Chambers taking the part of the man who’s wrongly accused of his wife’s murder while he was in a bar with a woman no one else saw. Kane’s version of the story makes more sense than Woolrich’s but then he didn’t have to reach book length.

Criminal lawyer Sonny Evans, who was an offstage character in A HALO FOR NOBODY, has a scene in “A Matter of Motive†(March 1947). It’s at his recommendation that Chambers is hired when a drugstore owner is charged with the murder of one of his clerks, who was blackmailing him over his sideline as a narcotics dealer, and with whom he had an appointment around the time of the killing.

The next most likely suspect is the dead man’s nightclub-singer fiancée, who was also the beneficiary of his life insurance policy. Chambers searches the scene of the murder and finds a letter indicating that the dead man was having an affair with his blackmail victim’s wife and was about to break it off. With two female suspects, both of whom admit they were near the crime scene at the crucial time, plus of course his client, who also had motive and opportunity, Chambers figures out who done it in a manner reasonably fair to the reader.

You’d never guess from the flippant title of “Kudos for the Kid†(May 1947) that it’s quite close to a traditional detective tale, with Chambers addressing his friendly enemy as “my dear Parker†and the lieutenant in turn griping about the PI’s Sherlock Holmes act.

Chambers happens to stop at a Fifth Avenue candy store to ogle a beautiful blonde staring into the shop window and is immediately invited to accompany her to an apartment hotel. What sounds like an invitation to bedplay quickly turns out otherwise: the blonde had lost a valuable emerald earring at a dance and was waiting for the person who had advertised in the newspaper, asking whoever lost the earring to meet him in front of the candy store, prove ownership of the jewel and take it back.

Matters are straightened out in the hotel’s tower suite but before leaving Chambers discovers the blonde’s wealthy father dead of two bullet wounds in the stomach. Parker and the police doctor call it suicide but Chambers insists that suicides don’t shoot themselves in the stomach and instantly deduces the murderer (who appears onstage for exactly four paragraphs), then pulls a huge bluff to make the culprit confess.

In the collection’s title story, “Report for a Corpse†(July 1947), a wealthy old woman hires Chambers to find out how her unfaithful husband, whom she’s refused to divorce (at a time when the only ground for divorce under New York law was adultery), plans to kill her. Shadowing the errant husband, Chambers discovers that he’s surreptitiously collected a huge supply of barbiturates.

Visiting his client’s stately home to report to her, he gets to meet the couple’s lovely adopted daughter and apparently has a quickie with her. Soon afterwards the older woman is found dead of an overdose of, you guessed it, barbiturates. Chambers fakes an alibi for the husband and then pins the crime on — well, I’d be a toad if I said more.

With five violent deaths and a plot rooted in events of a dozen years earlier, “The Shoe Fits†(July 1947) leads one to suspect that Kane had begun it as a novel and then, changing his mind, had boiled it down to the length of his other Esquire tales. In Hollywood to act as a $750-a-week technical adviser on a PI epic — perhaps a follow-up to THE BIG SLEEP? — Chambers is offered a bonus by the producer and director of the movie to bodyguard a Nevada casino owner who’s deeply in debt to the Mob and likely to be killed for welshing.

The guy is murdered before Chambers can take on the job but our sleuth suspects that it wasn’t a Mob hit, follows the trail back to New York and three deaths that took place years before, returns to Hollywood and wraps things up as usual. One of the central clues is gibberish except to dyed-in-the-wool New Yorkers and another stands out like W.C. Fields’ nose to anyone who remembers a little high-school German.

In “Suicide Is Scandalous†(June 1948) Chambers’ client is another old lady and his job is to prove that one of her stepdaughters, an unaccountably wealthy woman who according to the evidence shot herself to death in her Park Avenue apartment on a Sunday morning, was actually a murder victim.

If in fact she was murdered, the prime suspects would be the client herself and her other stepdaughter, each of whom inherits half under the dead woman’s will. With the bullet in her head clearly fired from her own gun and with a suicide note in her own handwriting found beside her body, Chambers seems to be up against a stone wall.

But with the help of a penmanship clue borrowed from A HALO FOR NOBODY, and after a fistfight with the murderer, he breaks down the wall and earns his fee.

***

Kane’s Esquire appearances were not limited to short stories. The magazine had published a condensed version of ARMCHAIR IN HELL (January 1948) and also ran condensations of his third, fourth and fifth novels, which I’ll discuss in another column, plus a single stand-alone short story, never collected (“Lost Epilogue,†October 1948).

During the 1950s Kane’s novels were all paperback originals, his short stories appeared usually in Manhunt, and he perfected the oddball narrative style known to his admirers as High Kanese. Perhaps I’ll explore these later too.