Tue 16 Apr 2013

A Review by Dan Stumpf: WE WERE STRANGERS (Book & Film).

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews[5] Comments

We Were Strangers (Signet #716, 1949) is an interesting book with an interesting story behind it. The author (Robert Sylvester) wrote the novel Rough Sketch (Dial Press, 1948), parts of which deal with the Cuban Revolution (referred to in To Have and Have Not) of the 1930s. Then when it was filmed as We Were Strangers he re-organized (but did not re-write) the chapters to conform to the movie. It might be fun some time to look up Rough Sketch and see how it differs, but for now Strangers offers entertainment enough.

The story starts off unpromisingly — a result of the chapter-shuffling? — with an off-putting stretch about a bunch of sycophants spending a weekend on a rich man’s island, but after about 50 pages things shift radically to the Cuban thing, with some really fine background, interesting characters (including a tough street girl named China Valdes) and details of a regime so casually brutal as to seem all the more chilling — embodied in Ariete, a murderous cop and one of the Great Bad Guys of Literature. Really. Every time you see him even referred to in the book, somebody dies or disappears, and the scenes where he stalks the Valdes girl are like something out of Night of the Hunter.

This gradually morphs into a plot to kill the dictator, engineered by Tony Fenner, a Cuban-American hustler who appeared in other work by Sylvester. We get some taut business with clandestine meetings, phony deals, and a lot of sweaty work as the conspirators dig a tunnel to plant a bomb. It’s good stuff, intercut with scenes of Ariete harassing China Valdes as he closes in on them, all culminating in an ironic conclusion that… that would be spoiling things to reveal. Suffice it to say it’s a suspenseful and emotionally riveting ride.

But the end of the story isn’t the end of the book, which moves on to a rather unexpected and haunting conclusion. Suddenly the characters get caught up in real life, with truly poignant results. And I have to say that when I think back on Strangers, I’m going to remember this ending and the bittersweet feel Sylvester imparts to it as the characters realize that the life-and-death struggle that brought them so close is now just a finished chapter in a story that has to move on.

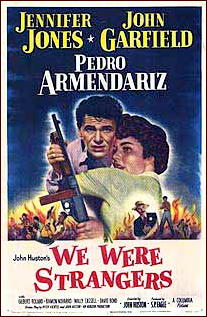

Like I said, there was a movie made of this (Columbia, 1949) and I can see why the themes of struggle and irony in Rough Sketch appealed to John Huston, who directed and co-wrote the film We Were Strangers.

Huston wisely jettisoned the sycophants on the island and (less wisely) replaced the sadder-but-wiser ending of the book with a blood-and-guts shoot-out. But his sure hand at directing the actors and action got severely undercut by budget constraints, or possibly just laziness; the stars never appear on any authentic Cuban locations, but only in unconvincing back-projection shots that make the whole thing look phony as a fast shuffle.

If you can get past that (and I couldn’t) the rest of the film has its moments. There are fine turns by Pedro Armendariz as Ariete, and Gilbert Roland in a supporting role that he credited with reviving his career. Jennifer Jones would probably be convincing as China Valdes if you could forget that she’s Jennifer Jones, but John Garfield just looks tired and bloated—perhaps understandable since he died just three years later. In all, I’d say We Were Strangers may be well-intentioned, but we know where the road paved with Good Intentions goes, don’t we?

April 16th, 2013 at 9:51 am

The reshuffling of the chapters certainly makes the paperback edition sound unique. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a copy, or if I had, it never made an impression on me as a book that I might want to read. Looks like I was wrong.

Robert Sylvester, by the way, has one other entry in Hubin’s CRIME FICTION IV, a book called THE BIG BOODLE (1954), which was also made into a movie, one starring a worn-out Errrol Flynn in 1957.

April 16th, 2013 at 1:54 pm

This is a really terrible film, Gilbert Roland’s presence notwithstanding. The Big Boodle is pathetic and Flynn looks worse than Garfield.

April 17th, 2013 at 6:56 am

I reviewed BIG BOODLE, either here or in DAPA-EM. Hey Steve, if it’s not posted here, I’ll dig it out & send it to you.

Anyway, I have a perverse affection for the later films of Errol Flynn; it’s oddly poignant seeing him trying to look young and charming (and sober) for the cameras, like an aging gunfighter stepping out into the street for just one more showdown….

April 17th, 2013 at 8:38 am

Dan

Your review of BIG BOODLE hasn’t been posted here, yet. Send it along and I’ll make sure it is.

April 17th, 2013 at 11:49 am

And here’s the link:

https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=21531