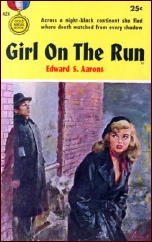

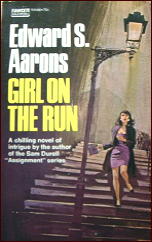

EDWARD S. AARONS – Girl on the Run. Gold Medal #424, paperback original, August 1954. Reprinted several times, including Gold Medal R2142; paperback, 1969.

Edward S. Aarons is best known, of course, for his long-running “Assignment†series, featuring the intrepid Cajun CIA operative Sam Durell. The first of these was Assignment to Disaster (Gold Medal, 1955), so Girl on the Run, being published a year earlier, might be considered a dry run for the series, without being a series novel itself, with no other books coming between.

The hero of Girl on the Run, Harry Bannock, is a structural engineer between jobs and at loose ends in France before heading back to the states, does not happen to work for any espionage organization, however. He’s just a guy, who because of a girl, Lorette O’Bae, whom he earlier loved and lost to a friendly rival, finds himself at her service, and soon thereafter, not surprisingly, involved way over his head in non-stop action and nail-biting adventure.

What the bad guys are after – and this includes his not-now-so-friendly former rival – is either (a) an enormously valuable medieval treasure, or (b) a secret, hidden lode of uranium, either of which will have a great influence on France’s political role in the postwar world.

Honed by working in the pulps, one imagines, Aarons’ prose is clear, clipped, crisp and clean. From page 19:

Bannock looked at Lorette then. He felt the urgency of Cobb’s words and knew that Cobb was speaking the truth about their limited time for decision. The girl’s eyes met his in a silent appeal. She looked small and trim, the red leather belt emphasizing her tiny waist and the flare of her softly curved hips. Looking at her, he knew that everything was unimportant beside the fact that he was in love with her. An intense desire for her came over him, and he looked at Cobb and the huge young man in the doorway and still he saw Lorette and the soft lines of her breasts and the way her chin lifted just a bit then. She was very beautiful. Suddenly he knew that going home to New York was a trifling matter. There was nothing for him in New York, after his years of absence. He had been on his way there from force of habit, because there was nowhere else to go. He had been living in all the far corners of the earth until now because he had been looking for something he hadn’t wanted to admit to himself, and now, when he looked at Lorette, he knew what that something was and he didn’t want to lose it.

From pages 33-34:

He tried to tell himself then that nobody would hurt Lorette as long as her kidnapers didn’t learn what they wanted to know. He knew he was lying to himself. The thought of her being in the hands of reckless men made him tremble, and the sweat stood out all over him. He got up off the cot and smashed at the steel door with his hands and yelled at the top of his voice. The cell was dark, and there were no lights in it. He kept smashing at the door and yelling and presently a dim bulb went on the corridor and he heard quick footsteps. It was the guard.

Here’s an action scene, from page 53:

When [the two men] suddenly jumped, Bannock kneed one and punched at the other’s face and then lowered his head and tried to ram between them to get off the aqueduct. The stocky man tripped him, and before he could rise again the other kicked at him, and Bannock rolled sideways in pain exploding all through him. The stones under his body slanted sharply and he shouted and felt himself slide toward the open end of the bridge. The sound of his voice was lost in the quick roar of the whirlpool below. For an instant he glimpsed the wide, staring eyes of the two men. For another instant he tried to cling to the edge of the slippery stones. His legs dangled in empty space. His fingers clawed for a grip. The stocky man grunted and stamped his heel on Bannock’s hand, and Bannock suddenly let go and fell through space toward the swift sucking current of the stream below.

On page 93, he becomes philosophical, the following thoughts going through his mind:

I remember a day in Maine in the spring, when I went fishing instead of going to school, and the sun was warm like this sun and the earth felt like this earth. I was twelve years old and Aunt Martha was already dying and I didn’t know it. If I went back there now and picked up a handful of earth, it might, by the chemistry of nature, be a handful of Aunt Martha, because we all belong to the earth and the earth is our final destination. The earth is our home. I’ve been in many strange corners of the world and never knew this before. And yet, because of the accident of birth and the familiarities of childhood, you can’t call this place or that place your home, but only one particular place, and for me that is a place far away from here. But if I went there, I still wouldn’t be home, because there is this emptiness I always felt and which I filled with of Lorette O’Bae. So this plot of earth or that one isn’t enough.

The sun that warms me now also warms Lorette. Somewhere nearby, perhaps within walking distance, she is asleep or just awakening in a bed she thinks is safe; but it isn’t safe, and I want to be with her and guard her and, if she will let me, to love her. And when I am with her again, then this or that earth will make no difference at all because it will be all one and the same. And if anyone tries to stop me from finding her and being with her, no matter who it is, including this thief sitting beside me, then I will send him to join and become part of this soil here. I never wanted to kill anyone and I still don’t want to kill anyone, because it’s an awful thing to take another’s life since there is nothing more important to a man than to continue in the casement of his body that holds his brain and his soul, if he has a soul. When the body is killed and the man is dead, then his identity is gone, and he no longer thinks or feels or observes or enjoys or suffers, and in a small way the earth itself is robbed by his death.

There is much to this story that would also be considered hard-boiled, and I would recommend at least the first 75% of the book to you, including the parts I quoted from. It is also true that the tale seems to get away from Aarons from that point on, out of control and misfiring at precisely the wrong time and the wrong place. He is beat up and left for dead at one point, for example, but he is not dead. With the use of not a single bullet, Bannock lives somehow, he recovers, and he prevails.

We knew he would, but all in all, I think (just maybe) it could have been made a teensy bit more of a challenge for him. Not that Bannock — if you were to ask him, given all that he goes through — would agree!

— February 2005

November 4th, 2015 at 2:29 pm

Even without the long quotes I provided, I remember much of the first three quarters of the book very well. The ending, which as you can see, I seem to have been not as happy with it at the time, nor do I remember it, not a single detail.

I’m just going to have to take my word for it.

November 4th, 2015 at 3:43 pm

Aarons is one of my favorite writers, though I haven’t read this one. I’ve found, more often than not, that writers are either great stylists or great plotters but are seldom both, or at least not as often as one would think. Chandler comes to mind. Aarons was a great stylist from character to milieu to pace, and his plot setups are always quite good. But I’ve read a lot of his books and at least once per novel, it seems, some crazy, improbable coincidence occurs that saves a plot that he’d dead-ended himself into or lost control of. Love him anyway, and one of my goals is to read every novel Aarons wrote. I’m about halfway there!

November 4th, 2015 at 4:00 pm

Stephen has it right; Aarons was one of the better graduates of the Chandler school of hard-boiled writing.

November 4th, 2015 at 4:10 pm

Ah, you’ve whetted my appetite for the golden oldies from Gold Medal, Fawcett, et al; I wish I could find copies at my used bookshop in my small town, but — alas — I have to rely instead upon vicarious pleasures through postings like yours. Thanks from R.T. at http://thesimpleartofmurder.blogspot.com/

November 4th, 2015 at 7:12 pm

Ronns’ “Murder Buys a Hat” (1942) is a fun mystery short story, from the pulps.

Its available free at Pulpgen:

http://www.pulpgen.com/pulp/downloads/list_by_author.php?page=59

November 4th, 2015 at 7:29 pm

This one just misses — thanks to sloppy writing — being in line with the kind of thing the better Brit thriller writers of the time were doing. Aarons just doesn’t trust the material or his own work, and instead gets lazy and relies on pulp to get him out of a tight, but up to that moment it is a damn good read, and I would still recommend at least 75% of it as superior and the other 25% no worse than most pulp plotting of the era.

But 75% of a damn good little thriller is a good 60% above most of his contemporaries, and I remember much more of this book than I would have expected from reading the passages quoted here.

Reading this though, and some of his better Durrell outings, I wonder if he might have done much more with his talent given a little chance and a bit more care applied to the writing. I always had a feeling Aarons was cruising when he might have let her into third and given it the gas.

November 4th, 2015 at 11:54 pm

I’ve found that “fall apart before it’s over” problem again and again in Aarons’ books, and yet the good parts are good enough to keep me reading them. Sometimes he does hold everything together all the way through, and those books are really fine.

November 6th, 2015 at 8:36 am

I read plenty of Aarons back in the Sixties and Seventies. I enjoyed the Durrell series despite its flaws.

November 6th, 2015 at 4:12 pm

I read some Aarons long long ago–so long ago I cannot remember the titles or, in fact, anything about them. I seem to recall liking them, tho.

November 6th, 2015 at 9:22 pm

Matt

Most of Aarons’ books are easy to find, if you go looking for them. I have a long way to go in terms of reading theSam Dureell “Assignment” books, though I have them all, most of them from various newsstands when they first came out. If you find you like one, you will probably want to read more.

November 7th, 2015 at 7:32 pm

Although Donald Hamilton is a better and generally more ambitious writer than Aarons, in all honesty I found the Durrell books more consistent reads than the Helm series which could vary from the brilliant first outing to the almost pointless THE BETRAYERS to some of the later books that all seemed to be the same book with virtually the same setting rewritten again and again to the point I could no longer separate titles or plots.

Aarons was a bit sloppy at times, but overall his imagination and his determination to keep the settings and backgrounds fresh in the Durrell books paid off for me as a reader. The best Durrell outings are not as good as the best Helm, but the worst aren’t as disappointing either. An average Durrell was generally better reading overall than an average Helm.

Maybe its just because Aarons didn’t seem to have any strong opinions about women in pants and American made cars.