Mon 4 Mar 2013

Reviewed by Dan Stumpf: TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT (A Book and Three Movies).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[11] Comments

From all accounts, Ernest Hemingway wrote To Have and Have Not (Scribner’s, 1937) in fits and starts, cobbling it together from two earlier short stories while mucking about in the Spanish Civil War. And frankly, it reads a bit sloppy and disjointed, with shifting time frames, clashing narrative modes, and here and there the terse, fascinating prose that made Hemingway a name. Reading it through, with its sudden jumps in time, location, narration and focus, one wonders if the legendary author was pointing the way for writers like Ken Kesey and Carlos Fuentes or just being lazy.

The first part deals with Harry Morgan, a charter boat skipper operating around Key West and Cuba who gets stiffed by a Mr. Johnson and helped out by Eddie, an alcoholic buddy (an important character in future incarnations of the book, but this is his only appearance here) when he’s forced to take on an illegal load of Chinese immigrants — a job that ends in gunplay and murder. This is pretty good stuff, violent and fast-moving, with Hemingway writing in the style of W.R. Burnett, with maybe a touch of James Hadley Chase.

Then we make a jump and it’s some time later, months or a year maybe, and Harry is now apparently smuggling full time and trying to make it home with a shot-up arm and a dying mate. This part is tough too, but Hemingway now spends time with a wealthy, officious politician who sees a chance to get some publicity by “capturing†Harry, who couldn’t put up much fight. Thus we get the first conflict between the “haves†and “have nots†— along with an infusion of social commentary into what had been just a tough crime novel.

Which sets the scene for part three: Harry is up against it now; his boat’s been confiscated and he has to get it back to do a job for some dangerous customers — so dangerous that murder and double-cross are taken for granted, and the crooked lawyer who sets up the deal (a violent bank robbery in Key West followed by escape to Cuba) is the first to go. In a tough, suspenseful scene that anticipates Key Largo, Harry shoots it out with his passengers and then …

And then Hemingway spends the last third of the book detailing the tribulations of a bunch of rich folks, with occasional contrasting scenes for Harry’s wife Marie. No kidding. What had been a tough crime novel on the order of Red Harvest is suddenly supposed to be Meaningful Social Drama. The idea, I suppose is to ennoble Harry Morgan and his people by showing us how effete and shallow their “betters†are, but it doesn’t come off.

Maybe I like David Goodis so much because when he writes a crime novel with a low-class working stiff or drunken stumblebum as the hero, that guy, be he ne’er so vile, is simply The Hero and ipso facto a man who gets our respect; he don’t gotta be Christ on the Cross too. When Hemingway turns Harry Morgan into the martyred representative of the Working Class, he loses me.

To Have and Have Not was filmed three times, and the first version (Warners, 1944) starred Humphrey Bogart, introduced Lauren Bacall, and was punctiliously faithful — to the title. Aside from that, it’s kind of jarring to see bits and pieces of Hemingway’s novel popping up here and there in what is essentially a Howard Hawks movie that seems to have little relationship to anything Papa wrote.

The story (written by Jules Furthman and William Faulkner) is moved up to 1940 and south to Martinique, which was at that time (like Casablanca) technically French but heavily influenced by the Third Reich. Naturally then, the would-be illegal immigrants become Free French resistance fighters, the officious politician becomes nasty Vichy cops, and Harry and his wife have now just met and call each other “Steve†and “Slim.â€

In this version of the story, Mr. Johnson doesn’t get away with stiffing Harry (this is Bogart, after all) but gets inconveniently killed in a shoot-out (one of those scenes from the book that somehow make their way into the film). Eddie, the drunk in the opening of the story is here played by Walter Brennan, and he sticks around for the whole movie. He’s rather good, too. So is Hoagy Carmichael as a friendly pianist and Marcel Dalio (also from Casablanca) as a protective hotel owner — a character who would later reappear in another Hawks film, Rio Bravo.

In fact, this film is much more Hawks than Hemingway, but it’s Howard Hawks at his best, which is saying quite a lot. Not much action, but what there is comes across nicely. The characters (including Lauren Bacall in her film debut) are skillfully developed, and the whole thing has that easy, improvised look that only comes from hard work and genius — and produces a classic.

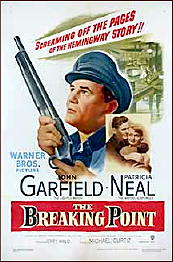

But I guess someone at Warners noticed that they’d bought this whole book and never filmed it, so in 1950 Director Michael Curtiz and writer Ranald McDougal came up with The Breaking Point, a noirish exercise with John Garfield as Harry Morgan, Phyllis Thaxter as his wife (now named Lucy!) and Patricia Neal as a gold-digger/femme fatale apparently added to throw a little glamour into the mix. Eddie is gone, replaced by Juano Hernandez as a dependable wing man, and the porcine Mr. Johnson is now Mr. Hannagan, played by Ralph Dumke.

The action is moved to Southern California, but otherwise this stays a bit closer to Hemingway and even includes the bent lawyer from the book, incarnated here by Wallace Ford looking agreeably slimy. There’s a tense race track robbery (not in the book of course) and an even more tense shoot-out on the boat as Garfield tries to thwart his would-be killers.

Unfortunately, the story spends a bit too much time with Phyllis Thaxter worrying about looking dowdy, Patricia Neal worrying about staying glamorous, and Garfield just worrying over bills and the odds against him. To Have and Have Not was a working class story, but The Breaking Point can’t decide whether to be a working class film or a caper movie in the mold of The Killers and this ultimately does it in.

Nothing daunted, Seven Arts/United Artists picked up the story again in 1958 and produced The Gun Runners, directed by Don Siegel and starring Audie Murphy as an unlikely Harry Morgan — now named Sam Martin(!) Eddie is back, this time played for seedy pathos by Everett Sloane of all people, and Patricia Owens (who that same year was the fretful wife of The Fly) is Audie’s wife Lucy.

The action is moved back to Key West and Cuba, and Mr. Johnson is now called Mr. Peterson, played with slippery relish by an actor named John Harding, who had a long career but seldom broke out of bit parts. Too bad, because he’s an all-too-brief delight here, cheerfully ruining a man out of sheer self-indulgence.

There’s a Mr. Hanagan in this version too, and he’s Eddie Albert, surprisingly nasty as the eponymous dealer in firearms who uses Audie to double-cross some very nasty customers. Albert is everything a movie bad-guy should be: smiling, generous, easy to get along with, and never losing that look behind his eye that says you mean about as much to him as a bug on his windshield, and you should expect to live about as long.

This is a pretty good movie. Siegel handles the action with his usual aplomb, Daniel Mainwaring’s script strays pretty far from Hemingway but moves things along neatly, and the playing is mostly well above average, particularly Patricia Owens, who manages to get across a very earthy lust for her husband. It’s nothing that’ll make you forget Bacall and Bogart, but it’s there and you can feel it.

My only problem with the movie is Audie Murphy at the heart of it. Like many real-life heroes (Wayne Morris comes to mind) Murphy could never convey genuine toughness on the screen, and this is a part that calls for it.

Too bad he has such a pivotal part in a film that would have been a lot better without him.

March 4th, 2013 at 12:52 pm

I remember thinking that TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT was about 1/2 of a good hardboiled novel and that the rest wasn’t so hot. I read somewhere long ago, maybe in some Hemingway bio, that when Hawks and Hemingway were on a hunting trip, Hawks bragged that he could make a good movie out of Hemingway’s worst novel, and then he asked Hemingway what that would be. Hemingway said, “TOO HAVE AND HAVE NOT,” and that’s how we got the movie. Don’t know if it’s true, but it’s a good story. Hawks cheated, though, and basically used just the title.

March 4th, 2013 at 1:23 pm

I’ve not seen THE GUN RUNNERS but noting Mainwaring’s name as screenwriter is good enough reason to track it down. As “Geoffrey Homes” he wrote some excellent mystery novels, probably best known for Build My Gallows High which later became the noir classic Out of the Past.

March 4th, 2013 at 1:52 pm

Dan:

I don’t think anyone could have done better in contrasting the three films. The Hawks is ultimately the good guys against the bad. The Garfield-Curtiz picture is social democracy at its worst and least entertaining. Now, too your point about Murphy and Wayne Morris. Right as relates to that pair. Not necessarily so for other decorated actor-veterans. Neville Brand, Lee Marvin, Gable, Taylor, James Stewart in his westerns. All capable of ferocity. As for Eddie Albert — winner of the Navy Cross.

March 4th, 2013 at 2:25 pm

Hemingway’s ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber’ and other short stories was the first REAL book I read, in English, at age 13, before I started to read German literature .

I still have that book,and it will be , as long as I live, be with me, a content .

The Doc

March 4th, 2013 at 7:22 pm

Trivia about Bacall. TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT was Bacall’s film debut, but it was not the first film she acted in, THE BIG SLEEP was. THE BIG SLEEP was filmed first but there was a War going on and the studios were rushing War pictures out before the War ended. TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT was filmed after THE BIG SLEEP but bumped THE BIG SLEEP release date. Everyone noticed the chemistry between Bogart and Bacall so they went back and added a scene or two to THE BIG SLEEP. One of those scenes added was the meeting between Bogart and Bacall where she talks about horse racing.

March 4th, 2013 at 7:55 pm

I’ve seen all three films and enjoyed them all. In my opinion THE BREAKING POINT with John Garfield is the best adaptation.

I first discovered Hemingway in the 1950’s when I was a teenager and he has remained a big favorite with me. I read most of his work several times and according to my notes I’ve read TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT four times. Here are my notes on the 4th reading, January, 2010:

“Not great like THE SUN ALSO RISES. Completely different from the Bogart/Bacall movie. The beginning and first half of the novel is good but then Hemingway leaves the Harry Morgan story and gets sidetracked with other characters. If he had stuck with just Morgan, this novel would have been a good, tough, hardboiled story. I believe part of the problem is that this was originally two or three novelets in SCRIBNERS MAGAZINE and Hemingway cobbled the stories together to make a novel.”

March 4th, 2013 at 8:09 pm

I haven’t seen “The Gun Runners”, but it sounds like it would be worth seeking out. “The Breaking Point” was excellent, far superior to the Hawks movie, and I say this as a huge Hawks fan. It has been showing up recently on TCM, and I’d definitely recommend it. In his introduction to the film, Robert Osborne commented that it was Hemingway’s favorite film adaptation of his work.

March 4th, 2013 at 11:42 pm

The last time “The Breaking Point” was on TCM, Eddie Mueller was guest hosting a film noir night of films. His opinion of it was, as a Curtiz film, it was his best!, better than “Casablanca”! Kind of made Robert Osborne look truly surprised. Not to mention anyone else watching at that moment. It’s a very good film, with Patricia Neal looking her sexiest! Reminds me more of the first half of Bogart’s version, followed by the last part of Bogart’s “Key Largo”. As far as the Audie Murphy version, I have yet to watch it, but I can’t beleive he could pull off a “tough guy” part at all. He comes off as too clean cut for me.

March 5th, 2013 at 4:53 am

Paul,

My favorite Curtiz film is THE UNSUSPECTED, which he also produced.

Dan

March 5th, 2013 at 7:50 am

Speaking of Audie Murphy, I’ve seen many of his westerns and been annoyed by the fact that he did not appear tough enough, etc. But the ironic thing is that he really was tough as hell. He was not only America’s highest decorated soldier but somehow managed to live through the horrors of war and still retain his sanity. As we know many veterans return in a shell shocked state and never are the same afterwards.

Yesterday, I saw THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE again and would have to say that this is Audie Murphy’s best performance.

March 11th, 2013 at 6:31 pm

To Have And Have Not was indeed Bacall’s first starring part. The Big Sleep, held back as you mentioned, with Confidential Agent her second release. I think you have confused Agent with the second Bogart picture.