Sat 9 Feb 2008

CYRIL HARE – The Christmas Murder.

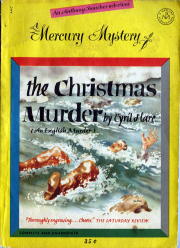

Mercury Mystery 190; digest paperback reprint. No date stated, but circa 1953. Original title: An English Murder. British hardcover edition: Faber & Faber, 1951; US hardcover: Little Brown & Co., 1951. Other paperback reprints: Penguin, UK, 1956, 1960; Perennial, US, 1978; Hogarth Crime, UK, 1986; House of Stratus, UK, 2001.

This is not a difficult book to find, in other words, if all you want is a copy to read. Even so, the only cover image I’ve been able to come up with is the one I discovered last week in a stack of previously unsorted digest paperbacks beside my desk. It’s a throwback to the Golden Age of Detection, in terms of plot, but the setting and general ambiance – postwar England – has the players at odds with each other for reasons not usually associated with the previously mentioned Golden Age.

Post-war England was in a stage of upheaval, with the lower classes beginning to feel that the upper classes perhaps need not always be bowed down to, and politicians on either side – and politics in general – were becoming more strident as a consequence. Clashes between various segments of society (the aristocracy vs. the radical socialists, for example) were growing more common, including (it appears) between the old, who remembered pre-war traditions, and the young, who did not. (Not to mention the young who simply wished the old would step aside, having had their day.)

Neither of Cyril Hare’s most commonly used series characters makes an appearance in this novel. Inspector Mallet was in six of the author’s nine novels. Francis Pettigrew, an elderly and somewhat embittered barrister was in five of them, with an overlap of three in which they both appeared. If this sounds like the beginning of a math problem, I apologize. (I am also not counting two collections of Hare’s short stories.)

Most of Cyril Hare’s mystery fiction, the author himself a barrister and a judge, deals with courtroom trials and/or the finer points of law, and British law at that. So does this one, so much so that the original title is a perfect fit. That the story takes place at Christmas time is almost entirely incidental. It’s only an excuse to get several members of one family together, along with a few choicely selected friends, at one time, at one place, and snowed in with no recourse to get along with one another – or not.

There are two detectives of note. First by default, Sergeant Rogers, the bodyguard of Sir Julius Warbeck, M.P.; and secondly — and one wishes that this were not the only detective he ever appeared in — Dr. Wenceslaus Bottwink, a history professor and a refugee from many ism’s in Europe. It is Bottwink who does the true detective work, looking on as an interested observer of both British society at the time and the small microcosm of the same that find themselves isolated in Warbeck Hall, the “oldest inhabited house in Markshire.”

In terms of “fair play” detection, it might help the reader if he or she were a historian him or herself, but on reflection at book’s end, I think the motive should have been clear, or at the least, clearer than it was to me at the time.

One disappointment to me, after finding myself elated at the early-on discovery of the kind of story I was in for, was that the book felt too short, without quite enough suspects nor sufficient false trails to be led down. There is an explanation for this. According to mystery historian Tony Medawar, An English Murder was based on “Murder at Warbeck Hall,” a half hour radio play broadcast by the BBC in 1948.

No matter. I will always gladly accept examples of detective work like this, no matter if short work is made of it or not. The social unrest that provides the setting is a pure 100% bonus.

February 9th, 2008 at 11:59 pm

Steve–

I had to laugh when I read your comment about a “stack of previously unsorted digest paperbacks.” I remember several years ago when you bought hundreds of digest paperbacks from me at Pulpcon. It’s nice to know that you are actually reading them. I figured you were using them as ballast like the ships used them when traveling from the USA to England.

February 10th, 2008 at 12:11 am

Thanks, Walker. I was wondering what to do with them. Next time I go to England…

February 10th, 2008 at 12:14 am

…On the other hand, there are a lot of good mysteries in that lot, some of them hard to find in their original hardcover editions. It’s too bad that most of them are abridged. This one by Cyril Hare happens to be one that wasn’t.

February 10th, 2008 at 6:38 am

Steve, I agree – this is a very enjoyable traditional mystery. At the time Hare died, he was working on a new book, featuring Dr Bottwink again. I’ve been allowed by Hare’s son to read the manuscript, but unfortunately he did not get very far with it, so it’s very difficult to tell exactly where the story was going to go.

February 10th, 2008 at 4:07 pm

Steve (pl excuse the familiarity, I don’t know your full name)- go to

http://www.classiccrimefiction.com/images/hareenglish.jpg

for a particularly nice cover image.

Yours sincerely

Myfanwy Denman-Rees

February 11th, 2008 at 10:27 am

Martin, I’m pleased but not surprised that Hare intended to use Dr. Bottwink as a character again, and it’s really a shame that he wasn’t able to. Bottwink reminded me of a Hercule Poirot without the ego, with more humor, and with a knack of seeing British society from an outsider’s point of view. Poirot could have done that, being Belgian, but I don’t believe Agatha Christie ever allowed him to.

Myfanwy, Thanks! That’s a good look at the cover, all right, but I get the impression that they’d rather I didn’t borrow it without permission. Perhaps I should. Ask, that is.

[Added later.] Martin, I see I forgot to mention that I am also green with envy!

January 25th, 2016 at 1:12 pm

I love this book. I just finished it for the second time and I can see myself reading it next winter too.

Mr. Edwards, do you know if the author’s family has any intention of doing anything with the manuscript? Whether handing it off to a capable writer or publishing it for its own value to Hare fans?