|

MILTON

K. OZAKI: A COLLAGE AND HOMAGE

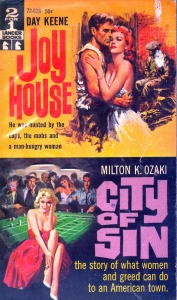

Originally written and compiled by Bill Crider For EyeCon, 1995 In addition to being the author of more than twenty mystery novels, many of them featuring private eyes, Milton K. Ozaki, who also wrote as Robert O. Saber, was a newspaperman, an artist, and the operator of a beauty parlor. You might know him as one of the stars of Bill Pronzini’s Son of Gun in Cheek (1987). In addition to devoting several pages to the glories of a non-PI novel (Dressed to Kill), Bill quotes what is probably my favorite line in the entire Ozaki oeuvre: “What the hell is this all about?” Hara demanded. “Damnit, I thought I made it clear that you weren’t to do any private dicking!” (Maid for Murder, 1955). But Ozaki was more than just a master of funny lines. True, his plotting was pretty wild (see the brief discussion of The Black Dark Murders below or the plot description on the back cover of The Affair of the Frigid Blonde reproduced below), but it improved. True, his writing style didn’t rival Raymond Chandler’s, but it improved, too. You can almost see the improvement happening in Ozaki’s steady progression up the ladder of paperback publishers. He started at the bottom with Phantom and Handi-Books, moved to Graphic, then to Ace, and finally to Gold Medal. The changes begin to become obvious in the Max Keene stories for Graphic. There’s a switch to third-person narration in the first Keene novel, though Ozaki still restricts himself to the thoughts of one character. But in A Time for Murder Ozaki uses multiple point of view. Keene is the main character, but he’s in only about a third of the book. From there Ozaki moved on to Ace for one more Carl Good (now Carl Guard) book and one book featuring a PI named Bob Wherry (OK, so this one is a stylistic throwback to the earlier books). Then he went to Gold Medal, where he did the best work of his career in a series of non-PI crime novels. He was a master of the simile:  From City

of Sin (1952): From City

of Sin (1952):Lee’s eyebrows did a startled rumba. [She] went tripping ahead of us down the hall on her high heels, with her hips waving a saucy goodbye. Her mascaraed lashes came down over her green eyes and did a little dance, like long rows of black-stockinged legs doing the can-can. . . . the words spilling out of her mouth like pebbles from a torn bag. . . . her hot, fetid breath in my face and my chest rolling around on her bosom as though on gigantic ball bearings. From Murder Doll (1952): [His heart] wasn’t beating – and his lungs were as still as a piece of cheese. I’ve been all around and busier than an ant in a bunch of grapes. From The Affair of the Frigid Blonde (1950): “. . . he’s been as busy as an ant in a new pair of pants.” . . . his eyes became as cold and blue as a pair of frozen grapes. With a face like that, Frank Laughton had about as much chance of avoiding recognition as a one-legged midget on crutches. From Maid for Murder (1955): Lisa Lincoln looked . . . as worn and haggard as a Sunday school picture of the wages of sin. She looked at me with eyes which were as uncommunicative as a pair of bottle caps. From Never Say Die (1956): It was 7:30 in the p. m. and the sands of time were pouring out like little potatoes through a broken bag. . . . with the reckless abandon of a bank president wasting a paper clip. I touched his hand, then dropped it. It was like clasping a handful of warm chitterlings.  A master of

originality: A master of

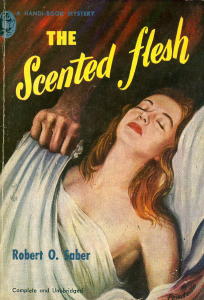

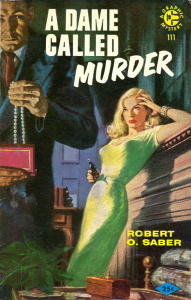

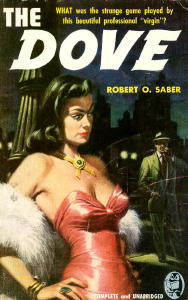

originality:From Maid for Murder (1955): A short, fat man, who looked as though he was pushing 60 – and as though that was his only exercise – murmured my name. From Never Say Die (1956): He had a big, florid face, a thatch of grey hair and, if the size of his gut was any evidence, pushing sixty was his only exercise. From The Scented Flesh (1951): [Morrie] had the reputation of being a shrewd, unscrupulous shyster lawyer, dealing mostly with the lower elements of society, but I liked him.... He practiced criminal law through choice, not necessity; he’d tried corporation law and had been bored stiff by it. As for dealing with crooks and social outcasts – what the hell? They have a right to be heard in court, and whom else would a criminal lawyer deal with anyhow? Shyster or not, Morrie was my idea of a good, practical mouthpiece. That was reason number one why I wanted to see him. Reason number two was this: by virtue of his contacts with the so-called underworld, Morrie knew as much as anybody about the location of the flesh-pots, the gin-mills and gaming joints.... It was all as familiar as breakfast cereal to Morrie. More familiar, maybe. From The Dove (1951): Morrie is quite a guy.... He’s a shrewd, unscrupulous, shyster lawyer, according to the other legal lights around town, but I like him because I know he is a smart, straight thinker and can be trusted. His principal clients are the so-called lower elements of society, but that is through choice, not necessity; he’d tried corporation law and had been bored stiff by it. As for representing crooks and social outcasts – well, they have a right to be heard, and whom else would a criminal lawyer deal with, anyway? From City of Sin (1952): Chandler has the reputation of being an unscrupulous lawyer because he deals principally with the so-called lower elements of society, but I like him and trust him. He practices criminal law through choice, not necessity. He’d tried corporation law for a few years and had been bored silly by it. Even crooks and social outcasts have a right to raise their voices in court, and whom else would a criminal lawyer deal with, anyhow? Shrewd or not, Chandler is my idea of a good, practical mouthpiece. By virtue of his contacts with the lower strata, he knows as much as anybody about the fleshpots, gin-mills and gaming joints, thepersonnel of the ruling gangs.... And what he doesn’t know himself, he can usually find out. From Murder Doll (1952): [Morrie] had the reputation of being a shrewd, unscrupulous, shyster lawyer, dealing with mostly the lower elements of society, but I liked him.... He practiced criminal law through choice, not necessity. He’d tried corporation law and had been bored stiff by it. As for dealing with crooks and social outcasts – what the hell? They’ve a right to be heard in court, and whom else would a criminal lawyer deal with, anyway? Shyster or not, Morrie was my idea of a good, practical mouthpiece. By virtue of his contacts with the so-called underworld, he knew as much as anybody . . . about the location of the fleshpots, gin mills, and gaming joints, the personnel of the mobs.... It was all as familiar as breakfast cereal to Morrie. From Too Young to Die (1954): [Morrie’s] office is next to mine,and I knew that he practiced criminal law through choice, not necessity; he’d tried corporation law and had been bored stiff by it. As for dealing with crooks and outcasts – what the hell, they have a right to be heard in court, and who (sic) else would a criminal lawyer deal with, anyhow?  Shyster or not, Morrie was my idea of a good, practical mouthpiece. That was reason number one why I felt like kissing him. Reason number two was this: by virtue of his contacts with the so-called underworld, Morrie knew as much as anybody about the location of the fleshpots, gin-mills, the gaming joints... It was all as familiar as breakfast cereal to Morrie – more familiar, maybe – and I sure as hell needed that kind of information. From A Dame Called Murder (1955): Barone ... had a bland, round face ... and the reputation of being a shrewd, quick-witted lawyer. His practice was almost exclusively with the so-called lower elements of society, but Barone practiced criminal law through choice, not necessity. And as for dealing with crooks and social outcasts, who (sic) else would a criminal lawyer deal with, anyhow? What the hell, Barone often said [Author’s Note: And God knows, he’s not the only one.], they got a right to be heard, ain’t they? A master of self-promotion: [keeping in mind that Professor Caldwell is the primary detective in several of Ozaki’s earliest books] From The Black Dark Murders (1949): [Captain Noonan said], “Did you ever read any of those stories about Professor Caldwell, the professor who dabbles in criminal psychology?” “No.” “This prof uses psychology and, even without any tangible clues, always puts his finger on the murderer.” [A few pages later, Noonan says to another character, a psychology professor], “I wondered if you’d read about a Dr. Caldwell, a psychology professor who solves crimes through the application of psychological methods. I was reading a story about him and– ” “This Caldwell is a fictional character?” “Well, yes. But – ” “I haven’t time for that sort of reading.” “I know, professor, but –” “I have no use for popular escape literature.” Aside from self-promotion, the plot of The Black Dark Murders is about as outrageous as Ozaki gets, and he gets pretty outrageous. This one concerns a series of murders on a college campus in metropolitan Chicago. All the murders take place outside on the campus after dark. It’s so dark, in fact, that characters who are standing next to one another or in fact sitting with their shoulders touching, can’t see one another at all [WARNING! SOLUTION REVEALED!]: “The murderer, due to a rare circumstance,

was

capable of seeing waves of light not visible to the normal eye...

The murderer had the curious ability to see by what is commonly

referred to as ‘black light’ – in other words, by light of a shorter

wavelength than 4000 Angstrom units.”

[END OF WARNING!] By the way, this book might be the very first to use college students sitting around saying “oh, wow” to a black light display. OK, they don’t really say “oh, wow,” but the effect is the same. Also included is one of the worst supposedly funny descriptions of a ballet that you’ll ever read. A master of describing what happens when a PI is hit on the head: From The Scented Flesh (1951): Then the world exploded. From Too Young to Die (1954): Then a rainbow exploded inside my head and the floor reached up for me. From Sucker Bait (1955): The pavement reached up for me. Then the elevator leaned over and slammed me on the head. From Maid for Murder (1955): I fell slowly forward into a deep black box. From Never Say Die (1956): A long black tunnel rushed at me . . . . [T]hen the back of my head exploded. A master of

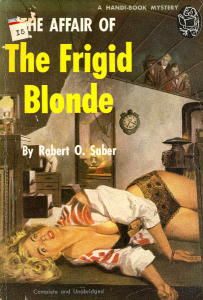

blurbology:

From The Affair of the Frigid Blonde (1950): All right, so Ozaki probably didn’t write the cover copy for his books. So he’s not responsible. So what? This stuff will give you an idea of his plots and the kind of sensibility that you don’t see revealed very often these days when someone is writing a Cast of Characters:  BOB STILLE, who failed to recognize the

vicious set-up when a prominent

business man and a luscious blonde first engaged his services.

But he was a private eye who knew his left eye from his right and

ultimately found that he could see with both of them. BOB STILLE, who failed to recognize the

vicious set-up when a prominent

business man and a luscious blonde first engaged his services.

But he was a private eye who knew his left eye from his right and

ultimately found that he could see with both of them.JOHN ADAMS, wealthy insecticide manufacturer and impostor, who made a bargain and wanted out. His plans for reneging were admirable, however there were a few bugs in it his insecticide couldn’t reach. MRS. FRANK LAUGHTON, pulchritudinous blonde living as Laughton’s wife, who had a mind as narrow and sharp as a knife blade and a set of warped morals that turned her steaming chassis into an ice box. ADA ST. CLAIRE, burlesque queen, and a good gal working at a hard racket for a future she never quite got. FRANK LAUGHTON, artist who traded his business for another name and a chance to devote his life to painting. A right guy who traded with the wrong people. JACK PIERCE, free-lance operative, a smart, ambitious detective who recognized opportunity when he saw it but always did things the hard way And let’s give Ozaki his due. He doesn’t always give you the stereotyped PI. In this book, his detective isn’t a handsome, devil-may-care, ladies’ man. He’s five-eight and a hundred and eighty-five pounds, smokes cigars, and has a nose. At least that’s what I think he says: “My face is round and ordinary, eyes brown, hair black with quite a little gray around the temples, nose yes.” Department of inconsistency: At the end of Murder Doll, Carl Good is married (to a woman he becomes intimate with in a nudist colony). The wife is never mentioned in any of the later titles. So what happened? Maybe I missed something. [And by the way, the nudist colony scenes are startling only for the nearly complete absence of any descriptive writing. What an opportunity missed! Where’s Orrie Hitt when you need him?] A MILTON K. OZAKI / ROBERT O. SABER

CHECKLIST

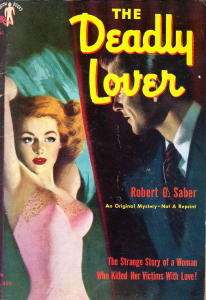

MILTON K. OZAKI:  The Cuckoo Clock. Ziff-Davis, hc, 1946. ** Handi-Books #100, pb 1950, as Too Many Women. A Fiend in Need. Ziff-Davis, hc, 1947. ** Handi-Books #116, pb, 1950. Too Many Women. Handi-Books #100, pb, 1950. Reprint of The Cuckoo Clock. The Dummy Murder Case. Graphic #33, pbo, 1951. ** The Deadly Pick-Up. Graphic #57, pbo, 1952. Graphic #92, 2nd pr., 1954. Berkley D2038, pb, 1960. Dressed to Kill. Graphic #79, pbo, 1954. (PI Rusty Forbes) Graphic #141, 2nd pr., 1956. Berkley D2007, pb, 1959. Maid for Murder. Ace Double D-135, pbo, 1955. (PI Carl Guard) [Paired with JAMES HADLEY CHASE Dead Ringer.] Never Say Die. Ace Double D-167, pbo, 1956. (PI Bob Wherry) [Paired with JOHN CREIGHTON Destroying Angel.] Case of the Deadly Kiss. Gold Medal #715, pbo, November 1957. Unibooks, pb, no date. Case of the Cop’s Wife. Gold Medal #795, pbo, August 1958. Wake Up and Scream. Gold Medal #879, pbo, May 1959. Murder Doll. Berkley D2016, pb, November 1959. Previously appeared as by Robert O. Saber. Inquest. Gold Medal #981, pbo, May 1960. City of Sin. Lancer Double 72-628, pb, 1962. Previously appeared as by Robert O. Saber. [Paired with DAY KEENE Joy House.] **These books feature series characters Professor Androcles Caldwell and Bendy Brinks, amateur sleuths, along with Lt. Phelan of the cops. ROBERT O. SABER: The Black Dark Murders. Handi-Books #96, pbo, 1949. (PI’s Phil Keene and Hal Cooper) Ramble House, trade pb, 2004. The Affair of the Frigid Blonde. Handi-Books #108, 1950. (PI Bob Stille)  The Dove. Handi-Books #130, pbo, 1951. Pyramid #90, pb, 1953, as Chicago Woman. The Deadly Lover. Phantom #502, pbo, 1951. (PI Carl Guard) The Scented Flesh. Handi-Books #124, 1951. (PI Carl Guard) City of Sin. Original Novels #722, pbo, 1952. (PI Pete Mallary) Carnival Books #922, pb, 1953. Lancer Double 72-628, pb, 1962, as by Milton K. Ozaki. Murder Doll. Phantom Books 510, pbo, 1952. (PI Carl Good) Berkley D2016, pb, November 1959, as by Milton K. Ozaki. No Way Out. Phantom Books 512, 1952. Chicago Woman. Pyramid #90, 1953. Reprint of The Dove. Too Young to Die. Graphic #90, 1954. (PI Carl Good) Graphic #150, 2nd pr., 1957. Sucker Bait. Graphic #99, 1955. (PI Carl Good) Graphic #156, 2nd pr., 1957. A Dame Called Murder. Graphic#111, pbo, 1955. (PI Max Keene) A Time for Murder. Graphic #123, 1956. (PI Max Keene) For additional commentary on Milton K. Ozaki, see his entry in the bibliography of Ziff-Davis Fingerprint Mysteries by Bill Pronzini, Victor Berch & Steve Lewis. _____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. |